Raging Clouds (Fantagraphics 2025), Korean mangaka and webcartoonist Yudori’s print debut, was released to widespread critical acclaim. Prior to Raging Clouds’ original French publication in 2022, Yudori was known for her popular webcomic Pandora’s Choice, a family drama set in nineteenth century America. Raging Clouds is a work of historical fiction set in the 16th century Netherlands revolving around Amélie, an impoverished Dutch noblewoman who must marry Hans, a merchant. The marriage is arranged, neither Hans nor Amélie are happy with the match; Hans wants a well-endowed common woman who can bear him many children and readily perform housework, and Amélie wants to pursue her independence and study the science of flight.

Their household is turned upside down when Hans returns from a trading trip in North Africa with an enslaved Asian woman Hans has named Sahara whom he forces into a sexual relationship. As the story develops, Amélie and Sahara form a close bond founded on similar fascination with flight, as well as an intense erotic tension. The narrative through line of the book follows Amélie as she designs a flying machine, a pursuit entangling her even more deeply with Sahara, Hans, and the mercantile greed of the Dutch East India Company when Hans takes credit for Amélie’s invention.

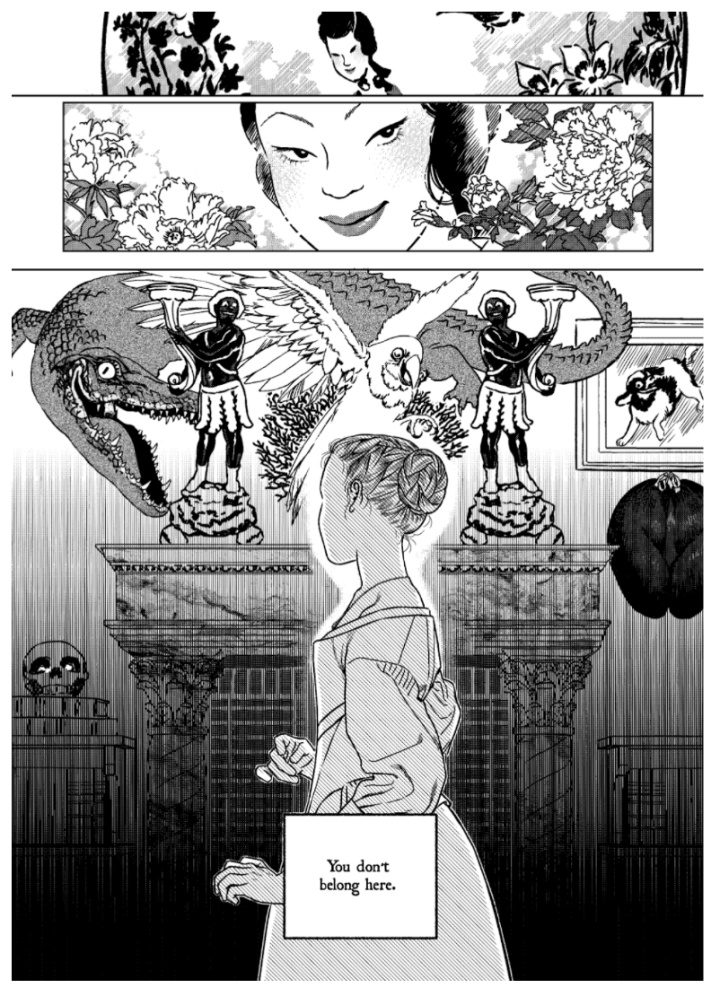

Raging Clouds is certainly Yudori’s most visually stunning work. The art pairs realistic, technically virtuosic backgrounds and environments with simpler organic and often erotic figures. Yudori makes full use of the space and time afforded to a cartoonist when working in the graphic novel form to flesh out a visual world rich in both symbolism and feeling. Even with teams of assistants, most serialized mangaka are rarely able to create a visual world as richly detailed as Yudori is in Raging Clouds’s 364 pages.

Scott McCloud notes in Understanding Comics that manga uses the contrast between cartoony characters and naturalistic environments to make a reader’s immersion as seamless as possible. Yudori’s figures aren’t nearly as cartoonish as someone like Osamu Tezuka’s, but the immersive effect is still very much present. Even the most beautifully rendered environments in Raging Clouds retain a cold aloofness. The eclectic and exotic collection of objects in Hans’s house taunts Amélie with her husband’s freedom and the avarice with which he cruelly ignores her.

It’s only when the focus of a scene becomes the body, in all its tortures and pleasures, that the overwhelming environmental detail dissipates, leaving a page awash in sensuousness. It is in these moments when Yudori’s work is at its strongest. These moments of intimacy are often paired with Amélie’s thoughts on God and divinity. They run the gamut from thought provoking and emotionally affecting to vague and morally confused. The phrase “No one is untainted in God’s eyes.” repeats twice through the book, spoken once by Hans and once by Amélie, but the nature of the story's characters makes the refrain ring hollow and naive. This is not a book in which every character is evil or wicked, nor is it a book in which each character is flawed in a normal way. Hans is pretty quantifiably evil; he beats Amélie, assaults her and Sahara; enslaving Sahara after murdering her lover. The other characters in the book’s main cast are flawed, but none as horrifically as Hans.

Even as it seems to criticize the totalizing morality of the Christian church, the book struggles to contend with the very real differences between the failings of Sahara and Amélie’s and those of Hans. The narrator bludgeons us over the head with the impossibility of perfection, all the while refusing to distinguish between imperfection and abject cruelty. The moral discourse of the novel crumbles when one attempts to expand the maxim to other characters; what, after all, did Sahara do to merit such condemnation?

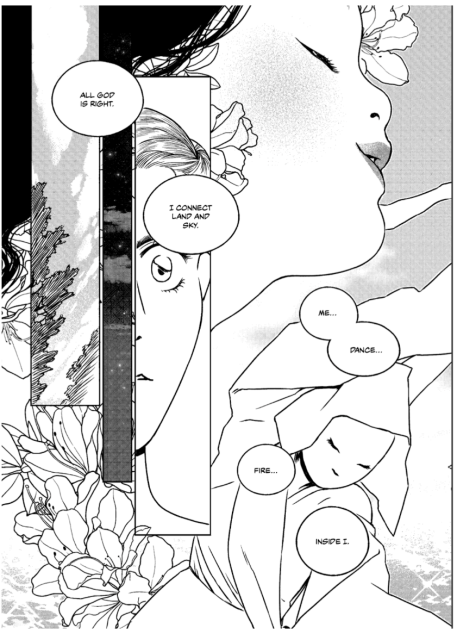

Although presenting a disappointingly shallow discussion of morality and religion for a comic that relishes so much in its length, the book suggests far more interesting and novel concept: that divinity rests in the eroticism of a woman’s body. Amélie’s initial understanding of divinity is defined solely by Christianity. However, as Amélie grows close to Sahara, she begins to find that there is a powerful divinity within her friend’s body. The two eventually become nearly impossible to distinguish for Amélie, as she recognizes a beauty in Sahara of which she was originally blind. Amélie finds herself obsessed with her friend’s body, wracked with visions of its naked beauty, overwhelming her as the light of God might a prophet. Amélie, unable to communicate desire outside the context of the divine and the moral strictures of Christianity is overcome by her discovery.

Raging Clouds never attempts to define the women's relationship through contemporary structures of desire and love. Yudori never uses the words ‘queer,’ ‘gay,’ or ‘lesbian,’ taking full advantage of comics' formal visual strengths to convey a desire her characters don’t have sufficient language for. It recalls Céline Sciamma’s 2019 film Portrait of a Lady On Fire, the story of two women falling in love in eighteenth century Brittany, one a noblewoman and the other an artist tasked with painting her. In Sciamma’s film, neither of the lovers nor, likely, the rest of the world, had a framework to define their attraction without condemnation, so Sciamma chose to make their attraction clear through their actions. Despite the lack of language, their relationship isn’t ambiguous. The pleasure and beauty of their attraction, as well as the pressures and torments of it, are on full, unabashed display.

By similarly refusing language’s ability to sum up queer desire a few centuries ago, Yudori’s work in theory becomes more queer and raw. There is certainly an erotic and explicitly sexual charge to the moments of intimacy between Sahara and Amélie, broken only once the need to intellectualize and define breaks in. In a climactic wordless moment in the book, Amélie masturbates, seemingly for her first time. Alone in a field of grass she imagines Sahara’s naked body. When she orgasms, rays of light emanate into the sky from her crotch in godlike pleasure. The scene zooms out to reveal Sahara watching silently from behind a tree wearing a slight smile. I bring up Sciamma’s film because it exemplifies the absurdity of calling a queer narrative queerbait because its creator chooses not to use contemporary language for queerness.

It is almost impossible not to read Raging Clouds as queer, although it seems some readers have alleged that the book is queerbaiting1. I was unable to find any reviews of Raging Clouds explicitly referring to the book as queerbait, but the opinion was pervasive enough for Yudori to post a swipe comic on Instagram titled “Is This Queerbait?”, addressing the notion that her book is not queer enough, and discusses non-European, specifically east Asian concepts of sexuality and same-sex intimacy.

Frankly, I think anyone who regards Raging Clouds as not a ‘real’ queer story, or as wholesale queerbait is missing some incredibly Sapphic content in the book. Raging Clouds is part of a long lineage of international queer literature, from Western classics like Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, to modern Asian masterpieces such as Notes of a Crocodile by Qiu Miaojin. It’s a text that explores desire outside of a hyper-sexualized realm. If the only way we can engage with queer comics is through the pornographic lens, we erase most of our historical and contemporary canon.

Unfortunately, much of Raging Clouds is all set-up with very little pay-off. Its ending is rushed, undermining the complex interior lives of its characters and revealing how little subjectivity Sahara is afforded throughout the book. Without revealing too much, Hans dies in a hot air balloon crash after impregnating Amélie. Amèlie is left with Hans’s money as his widow. Only fourteen pages of the 370-page volume are dedicated to life after Hans’s death, seven years after the fact. Sahara, still enslaved, seems to be tasked with the childcare of her rapist’s son, who tells her “Grandma says you’re a man-eating whore and you killed my father.”

After reading over 300 pages of Hans’s brutality, the child’s words are a brutal reminder of all that Sahara has gone through. They shouldn’t be taken lightly, but Sahara’s only reaction is to smile brightly. It’s then that we realize Sahara is still enslaved, justified by the notion that she can’t be tried for Hans’s death if she remains Amélie’s slave. The whole back and forth is founded on some serious leaps in logic that none of the preceding story supports, including the fact that there is no reason for anyone to think Sahara was responsible for Hans’s death, and that Amélie, who created the hot air balloon in the first place, is a much more likely target for any accusations. Furthermore, the notion that it's for the best for Sahara remaining enslaved is naive, bordering on condescending, her final moments in the book defined by caring for the racist child of a murderous slave-owner.

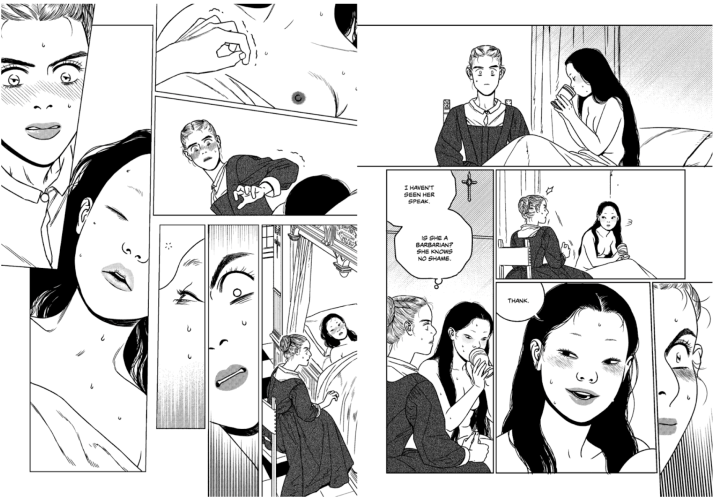

Throughout the book, we are given very few glimpses into Sahara as a person with subjectivity. The reason ostensibly being that Sahara does not speak Dutch very well, but by the end of the book she's fluent, using her voice to excuse her enslaved status. She is given almost no interiority, we’re never privy to her thoughts or emotions beyond vague facial expressions and short sentences that convey very little about herself, her culture, or how she feels about being enslaved. She oscillates between tough and competent to meek and dumb with no rhyme or reason, while at times seemingly enjoying being assaulted by Hans. Comics readily offer their creators formal avenues for characterizing people beyond just dialogue. Thought bubbles, captions, and narration are all immediately available tools Yudori forgoes in writing Sahara; we never even learn her real name.

While Sahara has very little characterization, Amélie actually has an incredibly complex interiority, with motivations and desires almost constantly in painful conflict. Unfortunately all of her complexity is wholly undermined by the book’s final pages. In them, the narrator tells us “Amélie was a simpleminded girl,” running contrary to everything we know about her, before saying “Men told her of elephants and unicorns that frolic in faraway lands. She wouldn’t dare to travel so far,” despite the fact that she originally designs her flying machine in the hopes of traveling with Sahara to Asia, on the other side of the world.

The narrator closes saying “She [Amélie] looked at the land. It was taken by men. She looked at the sea. It was also taken by men. So she decided to build her own kingdom of land and sea and keep the gate shut forever. But you’d never know, would you?” The monologue is confusingly unfounded, relying so heavily on the appearance of poetic depth that it provides more questions than answers. We don’t know anything about the kingdom she built after Hans’s death, we don’t know what it means that it is of both land and sea, and we don’t know what it means that its gate is closed to us.

In an online comic addressing accusations of queerbaiting, Yudori wrote that she had “pledged an oath to never make a story in which the main characters find a romantic happy ending,” and that “if you want to be ‘rescued’ by fiction, save your time and read the Christian bible or watch a Disney movie.” Reading this, I was taken aback. The suggestion that a person looking for a queer book with a happy ending is a childish, naive reader is strikingly offensive, and the added notion that such a person might find what they’re looking for in Disney movies or the Bible ignores that fact that neither the Bible nor Disney movies are at all queer, as well as the homophobia justified by the bible for hundreds of years. Yudori’s assertion also ignores the happy ending tone wrapping up the book's narration, even as Sahara remains enslaved, and Amélie’s discoveries are hidden even from her own child.

Raging Clouds is ambitious in length, and beautifully drawn, but ultimately the writing crumbles under its own weight. It is a rare book that I finish thinking it would be improved by a couple hundred more pages of story. Raging Clouds may be one such case.

The post Raging Clouds appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment