It was one war, one battle, one conflict after another, a state – Valuska gazed at the crushed terrain in front of him – where each event was self-evident, and it wasn’t as if there was anything surprising about this...

-Laszlo Kraszynahockai. The Melancholy of Resistance

“I know you want peace on Earth,” Dave Edmunds sings. “But we got to kill the monster first.” Only later do you learn the monster is doctors and nurses and babies and little girls with flowers on their skirt, all of them, “underneath the rubble... crying for the dead.” For more than three decades, Joe Sacco has been writing and drawing about monsters. They have been killed by defenders of land they believed God gave them 4000 years ago, or to make up for what they believed the Turks cost them in 1390, or, in his most recent book about Hindus and Muslims in India, in defense of cows. To be fair, no one was actually killed in The Once and Future Riot (2025) for eating a Jumbo Mac, but, by book’s end, some states had made it illegal to possess one and, in a few, slaughtering Elsie could mean life behind bars. (All artwork herein from The Once and Future Riot by Joe Sacco, Metropolitan Books, 2025)

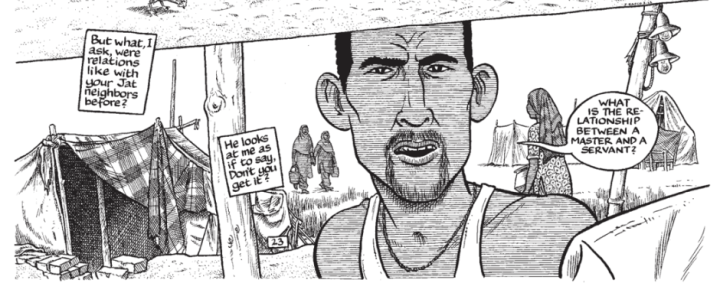

At Riot’s center are two-weeks of violence in 2013 in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh. Houses burned; tens of thousands fled; estimates of the dead ranged from dozens to hundreds. Sacco visited the following year, not to uncover the “truth” of what had occurred. His earlier ventures into combat reporting had convinced him that was impossible. Peoples’ memories faded or conflicted with other peoples’ or were distorted by bias or colored by subsequent events. Records were falsified or slanted. His own reporting could be shaped by preference and belief. Sacco sought instead, “the fiction, the myth, the imposter” that stood in truth’s stead.

His jumping-off point is the killing of a young Muslim man by two young Hindu men – and the killing of them by a Muslim mob. Following these second killings, several Muslims were arrested – but freed the next day by politicians courting favor with that community. Then eight Hindus were arrested in connection with the Muslim’s murder, which led to a call for a mass protest by leaders of the Hindu community – and a responsive call for a mass protest by leaders of the Muslims. Fearing the consequences of competing rallies, the government banned all public gatherings of more than four people. Both sides ignored this ban. Thirty-to-40,000 showed up here; 60-70,000 showed up there.

His jumping-off point is the killing of a young Muslim man by two young Hindu men – and the killing of them by a Muslim mob. Following these second killings, several Muslims were arrested – but freed the next day by politicians courting favor with that community. Then eight Hindus were arrested in connection with the Muslim’s murder, which led to a call for a mass protest by leaders of the Hindu community – and a responsive call for a mass protest by leaders of the Muslims. Fearing the consequences of competing rallies, the government banned all public gatherings of more than four people. Both sides ignored this ban. Thirty-to-40,000 showed up here; 60-70,000 showed up there.

The feared consequences consequenced. Following the killings and burnings, 20 men were arrested here; 50 were arrested there. Thousands of Muslims ended up in displacement camps. A system to compensate victims was paid out so arbitrarily and capriciously a tsunami of discontent and ill will followed.

II.

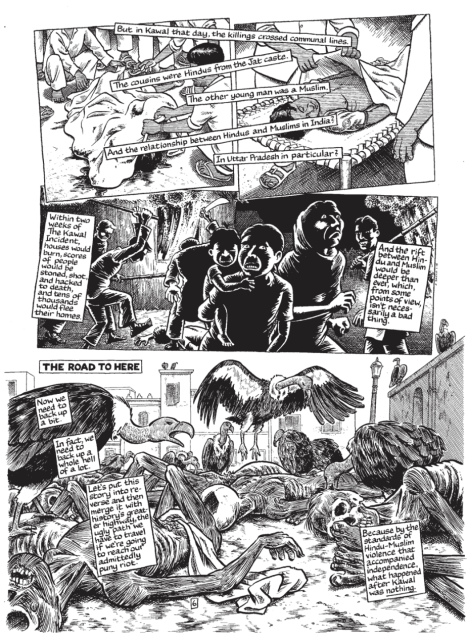

The violence upon which Sacco reports is always rooted in history. “(P)ast and present...,” he says “are part of a remorseless continuum (planting) hatred in hearts.” The point along these continua he chooses to begin his reports, I suspect, influences the conclusions he draws. In the Balkans, it is the break-up of Yugoslavia in 1991. In the Mid-East, it is the creation of Israel in 1948. In Riot, it is Great Britain’s setting aside part of its empire in 1947 for a Muslim-majority state, Pakistan and a larger portion, India, for a Hindu one. As an exercise of international diplomacy, partition did not work out as well as, say, the Marshall Plan. More than 12 million people left their homes. As many as 2 million may have been killed. This should not have been a surprise. Hindus and Muslims had been killing each other in India for over a century. With time out for World War II, there had been at least one riot a year since 1921; death counts reached into four figures.

Sacco quotes a journalist-associate for the proposition that after partition India remained free of “communal violence” until 1992, when 150,000 Hindus burned down a 16th century mosque Muslims had built upon the believed birthplace of the Hindu god Rama. This proposition is untrue. Wikipedia lists about 30 Muslim-Hindu riots between 1948 and 1991, often with hundreds of fatalities. (During the same period, other riots claimed the lives of Assamese, Dalits, Kannadigas, Marathis, Sikhs, and Tamil. More recently, Bengalis, Bodos, Christians, Kukis, and Meiteis have been added to the charnel ground.)

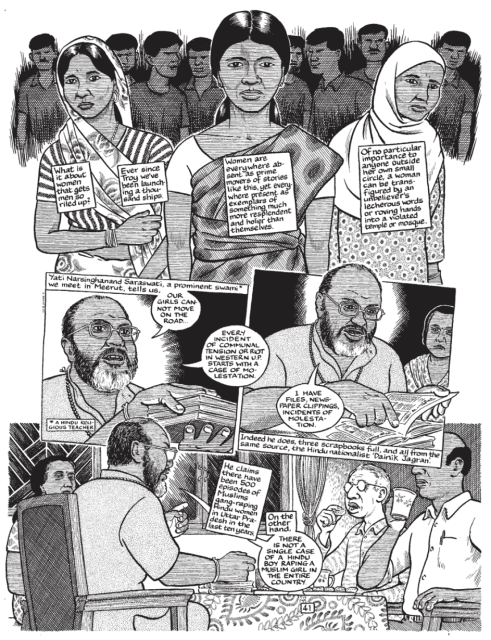

Up to 2000 people died in riots following the mosque’s burning. After 1992, there were another dozen or so homicide-resultant Hindu-Muslim clashes until the one on which Sacco focused. In 2002, in the worst, following the torching of a train containing Hindu pilgrims, 2000 may have died. By 2013, the blood-letting had slackened, but Hindus in Uttar Pradesh believed Muslims were being taught to gang-rape and impregnate Hindus and claim their babies in order to increase the Muslim share of the population, while Muslims were saying this slander had been manufactured to justify the beating of Muslim boys found where Hindu girls were present.

III.

Sacco is a courageous, dogged reporter. He ventures down streets too mean for many. He interviewed dozens of people on both sides. Villagers. Civic leaders. Farm laborers. Land owners. Journalists. Attorneys. Police officers. Religious figures. Victims of violence and its perpetrators. He pursues leads others provide and initiates avenues of inquiry himself. He is dedicated, serious, thoughtful. He tries to smooth his partisan edges with fairness; he can be skeptical when reason for skepticism socks him in the nose. His sentences are clear and clean and lead readers to a shudder-inducing WOW! His strength though, is his graphics.

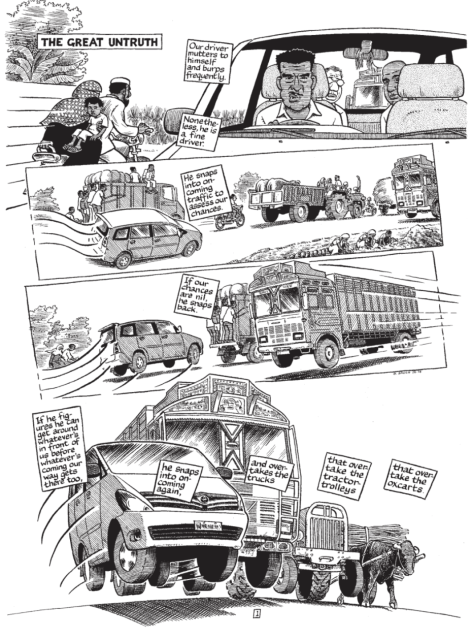

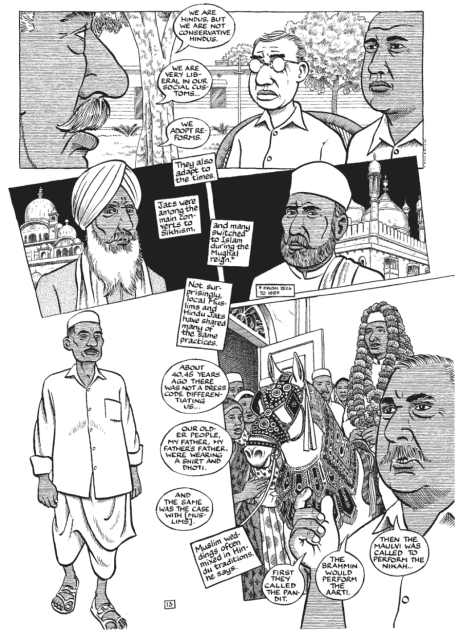

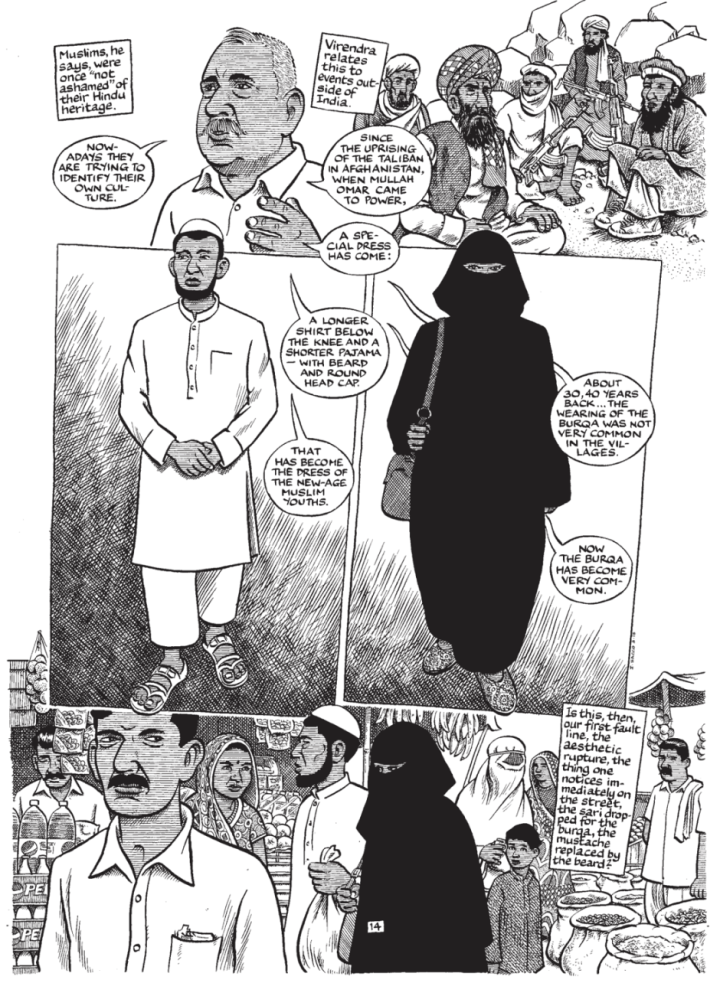

His layouts are imaginative. They proceed with stately regularity or careen across the page. Border lines may contain his panel or dissolve and let them flow. His backgrounds are generally pure white, but shadows and darkness swoop in and descend when fear and horror are to be conveyed. Basically he renders what he has seen or been told, but on occasion, as in a ghastly depiction of vultures feeding on corpses, he accesses the grotesque in summary of history’s march.

Sacco is adept at capturing details which portray a way of life. Oxen in streets. Sugar cane stalks and sheaves of wheat on heads. Swords and clubs in upraised arms. The furious eyes and bared teeth of the men who wield them. Women are colorfully dressed and men more drably and uniformly, emphasizing their military-like dominance of these villages, which women merely serve to adorn.

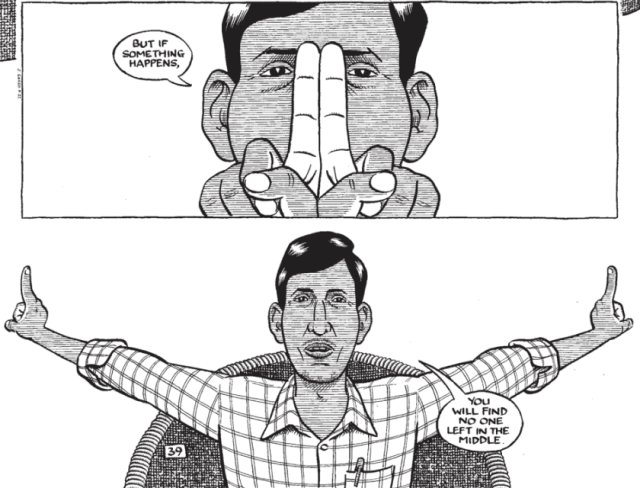

Sacco’s art relies on facial close-ups. There may be no page without one. (Even in his crowd scenes, distinct faces emerge.) He captures wrinkled brows and stubbled jawbones. His faces express sorrow or fatigue or rage or ennui. (The rendering of a smile lands like a slap.) The sense one gets is of people buried under centuries of poverty, denied education, health, advancement, weighted down as much by oppression as the bundles on their heads.

Most of Sacco’s panels strive for drama-invoking realism. The most “cartoony” is when he draws himself. His whiteness is palpable. His over-sized, circular glasses have no eyes behind them. Even an unconsciously rendered lack of vision for a reporter seems to recognize a work impediment.

Sacco does most of his research before visiting a country. His post-visit time is spent drawing. This allocation of labor makes for visual excellence but causes verbal problems. It is as if he dropped into a bunker when he returned from India, slammed the door, drew the blinds, and sat at his drawing board, not allowing onto it anything that occurred outside.

While in India, one or two people showed Sacco newspaper articles or hospital records, but these people were partisans, and the information they provided supported the positions they put forth. In the 11-years between his travels and the publication of Riot, Sacco seems to have barely deepened his initial impressions. (He does not even seem to know if any of the killings he reported resulted in trials and/or convictions.) I found a single footnote, authenticating a single quote by referencing “a later court proceeding and media reports.” By comparison, “America’s Vigilantes” (TNYT Magazine. Oct. 5, 2025), Matthieu Aikins’s report on murders by American Special Forces troops in Afghanistan in 2010 and 2012, which I happened to read at about the same time I read Sacco, supplemented his interviews with information culled from books, personnel and detainee files, and military, court and vital records, providing weight and significance to Aikins’s piece. Sacco may not have had this amount of paper available – and India probably didn’t have much of an FIA to help him – but the narrowness of his aperture suggests either (a) that this level of violence was of interest to few in positions of Indian authority – as in, what’s-a-couple-dozen-dead-bodies-out-of-9-million-in-country-annually? – or (b) that he was less inclined to in-depth investigative journalism than recounting personal experience and belief.

IV.

If Sacco explained why he went to India, I missed it. Even if he did, I was curious about his choice of atrocity. India’s history provided several where the death toll was higher, and he had already shown with Footnotes in Gaza (2009),which reported on events nearly 40-years prior, he does not limit his investigations to the contemporary. Might he, I wondered, have been looking for a chance to make an already fermenting point, instead of launching a journey to see what lay at its end? Might he have needed a point?

If Sacco explained why he went to India, I missed it. Even if he did, I was curious about his choice of atrocity. India’s history provided several where the death toll was higher, and he had already shown with Footnotes in Gaza (2009),which reported on events nearly 40-years prior, he does not limit his investigations to the contemporary. Might he, I wondered, have been looking for a chance to make an already fermenting point, instead of launching a journey to see what lay at its end? Might he have needed a point?

In any event, one is offered which he grabs. It comes from Zile Singh, whom Sacco describes as “a professor of political science at Sanjay Gandhi’s Postgraduate College in Meerut,” a city in Uttar Pradesh. Sacco introduces Singh on p.16, and he reappears several times thereafter. His first of significance is when Sacco reports in a panel caption claims that both Hindus and Muslims had used the riots to fire up their constituencies for an upcoming national election, but allows Singh to say below, without challenge, that this assertion was a media-created lie. The riots, Singh declares, were planned solely by the right wing Hindu nationalist Bharantiya Janata Party, which saw them as the only way they could win the election. The BJP won; the ultra-rightist Narendra Modi became prime minister; and laws brutally discriminating against Muslims followed.

Sacco then gives Singh the book’s final words, which, in effect, make them his final words too. “Public sentiment can’t be controlled,” Singh says.” Riots can’t be controlled.” They are “a curse to the country,” which have de-legitimized democracy as a form of government. Sacco’s concluding image is a full page of upraised arms clenching swords, scythes, axes, and clubs. His concluding thought is that riot will follow riot into a time unknown.

Winston Churchill may be your prototypical old, white, male, cigar-puffing imperialist bogeyman, but his observation “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all other forms” still holds water for me. Neither Sacco nor Singh say what type of government they prefer. Monarchy? Dictatorship? Oligarchy? Neither suggests that problems with democracy could be fixed by educating citizens so they made better decisions. Neither proposes building a society which treats its citizens equally enough to reduce conflicts between them. Neither limits their condemnation of democracy to (supposedly) less developed countries, which may not be suited for it. [In On Gaza (2024), repelled by the slaughter Israel carried out, aided and abetted by the US, Sacco muses “Are we still giving points for democracy?”] Ironically, one person who probably agrees with Sacco about consigning democracy to history’s dust bin is Modi, who, the moral philosopher Susan Neiman has pointed out, “has dismissed human rights as a Western concept,” another example of former colonizers dictating to the formerly colonized.

When it comes to Gaza, repulsion has been well-earned. But at a time our president seems determined to replace 250-years of constitutionally expanded, if still unsatisfactory, social progress with all the molar-cracking, blood-boiling, demon-determined despotism he can jam up our rectums, Sacco’s conclusion seems a risky bone to toss dogs. (For sheer, loosely-wired crankiness, in this respect he brings to mind Robert Crumb.) And democracy seems not to have served India too badly. Life expectancies have more than doubled since independence. In terms of income equality, one source has India among the best countries in the world. (Of course, under another, there was less inequality under the Raj. And a third says Indian statistics are so incomplete and inconsistent, there is no way of knowing.)

When it comes to Gaza, repulsion has been well-earned. But at a time our president seems determined to replace 250-years of constitutionally expanded, if still unsatisfactory, social progress with all the molar-cracking, blood-boiling, demon-determined despotism he can jam up our rectums, Sacco’s conclusion seems a risky bone to toss dogs. (For sheer, loosely-wired crankiness, in this respect he brings to mind Robert Crumb.) And democracy seems not to have served India too badly. Life expectancies have more than doubled since independence. In terms of income equality, one source has India among the best countries in the world. (Of course, under another, there was less inequality under the Raj. And a third says Indian statistics are so incomplete and inconsistent, there is no way of knowing.)

Not only is Sacco’s conclusion disturbing, he seems to employ a journalistic sleight-of-hand to reach it. Riot progresses along what seems a straight time line, from Sacco’s arrival in Uttar Pradesh, through a sequential series of conversations he had, leading to Singh’s democracy-damning conclusion. Sacco situates Singh’s assertion the BJP planned the riots in the middle of this narrative and his conclusion of perpetual riots at its end. But examine how Sacco set this up. The riots occurred in August and September 2013. Modi was elected prime minister in May 2014. Sacco arrived in India “more than a year” after the riots, so he already knew who won the election and may have suspected what he would make of it. And as far as I can tell, Sacco interviewed Singh once, which would have been after the election, too.

By dispersing the Singh interview across an expanse of time, rather than confining it to when it occurred, Sacco creates the illusion that Singh’s take on the BJP’s scheme was expressed before the election and his condemnation of what democracy had wrought after it. This increases narrative drama, while obscuring that both of Singh’s analyses were ex post facto speculations. Sacco could have begun with his arrival, admitting he was seeking an explanation for Modi’s election. Then he could have positioned his interview with Singh when it occurred in actual time. Sacco could then have interviewed the villagers and community leaders, testing Singh’s theories rather than swallowing them whole. Did the people feel manipulated? Did the riots change their votes?

By excluding 11-years of outside information from his creative bunker, Sacco further limited his ability to evaluate Singh’s doomsday forecast. This is unfortunate, for if riots had abated, Singh’s conclusions about the effects of those in Uttar Pradesh would have been of little significance. And if riots had continued willy-nilly, Singh’s conclusions might have been considered insignificant as well. Well, I checked; and in the decade before August 2013, India had about 10 riots, causing 150-200 deaths. In the decade following, it had about twice as many riots but the number of fatalities was similar. So, a riot a year, 15 or 20 dead per. Pulling the plug on democracy on that basis makes throwing the baby out with the bath water seem sound house keeping practice.1

V.

Neither Singh nor Sacco liked how the vote turned out. Neither do I. But blaming democracy seems crock-shit stupid. You do not need elections to call forth horrors. During my lifetime, some or all of the following occurred: World War II (70-85 million killed); Chinese Civil War (4-9 million); Second Congo War (3-5.4 million); Nigerian Civil War (3-4 million); Korea (2.5-3.5 million); Soviet Afghan War (1-3 million); Bangladesh (0.3-3 million); Ethiopia Civil War 1.75-2 million). I daresay campaign strategy hardly factored into any of them. While I was reading Riot, The New York Times reported on a single day that 400 people had been killed in a single hospital by a single Sudanese paramilitary unit, which is a third more than the highest estimated total of those killed in Uttar Pradesh, and 119 were killed in a drug raid in Brazil, which more than doubles the number killed in the atrocities committed by the Israeli army, which Sacco made the subject of his 400-page Footnotes.

Neither Singh nor Sacco liked how the vote turned out. Neither do I. But blaming democracy seems crock-shit stupid. You do not need elections to call forth horrors. During my lifetime, some or all of the following occurred: World War II (70-85 million killed); Chinese Civil War (4-9 million); Second Congo War (3-5.4 million); Nigerian Civil War (3-4 million); Korea (2.5-3.5 million); Soviet Afghan War (1-3 million); Bangladesh (0.3-3 million); Ethiopia Civil War 1.75-2 million). I daresay campaign strategy hardly factored into any of them. While I was reading Riot, The New York Times reported on a single day that 400 people had been killed in a single hospital by a single Sudanese paramilitary unit, which is a third more than the highest estimated total of those killed in Uttar Pradesh, and 119 were killed in a drug raid in Brazil, which more than doubles the number killed in the atrocities committed by the Israeli army, which Sacco made the subject of his 400-page Footnotes.

A slain person is a slain person. Each leaves behind resentment and grief. Which deaths becomes a focus of attention is a matter of a reporter’s drives, a public’s demands, a media’s cravings. So the choice of subject for Sacco suggests something beyond the number of tears shed or garments rent is determinative.

Democracy, Churchill might well have said, may be the bloodiest form of government, except for all other forms. Ever since Cain slew Abel out of personal jealousy, as some would have it. or as a pre-figuring of all herder-farmer conflicts, as would others (See also: Shane), people have found reasons to kill one another without seeking to increase voter turnout. Slipping everyone LSD, in Timothy Leary's opinion, would be one way to reduce the slaughter. Meditation, counseled Trich Nhat Hanh, is another. Do away with tribes, nations and religions, my wife would say (I agree.) Recognize we are all one and in this together. I admit ridding the world of democracies may be an easier fix.

Phil Klay, a Marine Corps combat veteran and National Book Award winner, has pondered if his writings are “fulfilling a civic obligation, exploring a personal obsession... or simply screaming into the void.” I wonder if Sacco’s travels have led him to a similar ledge of despair. He visited war zone after war zone. He found decent people in every one. They fed and sheltered him. With them, he sang and danced. They shared their hopes for marriage and profession. They asked for American jeans and the lyrics to songs by The Rolling Stones. His heart went out to them.

And he heard of rape and mutilation and death from stone and sword and club and fire, from iron rods and 2000-pound bombs. He recently told an interviewer he is stepping back from journalism because “drawing human suffering realistically has become more difficult and unpleasant. I need other ways of approaching the same subjects that are a little less visceral.”

After all these wars may he find peace.

The post A Scream Into the Void appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment