What is a history? Is it an account of the past? an explanation of the present? a guide for the future?

Ben Passmore's Black Arms to Hold You Up: A History of Black Resistance is something else: a search for identity.

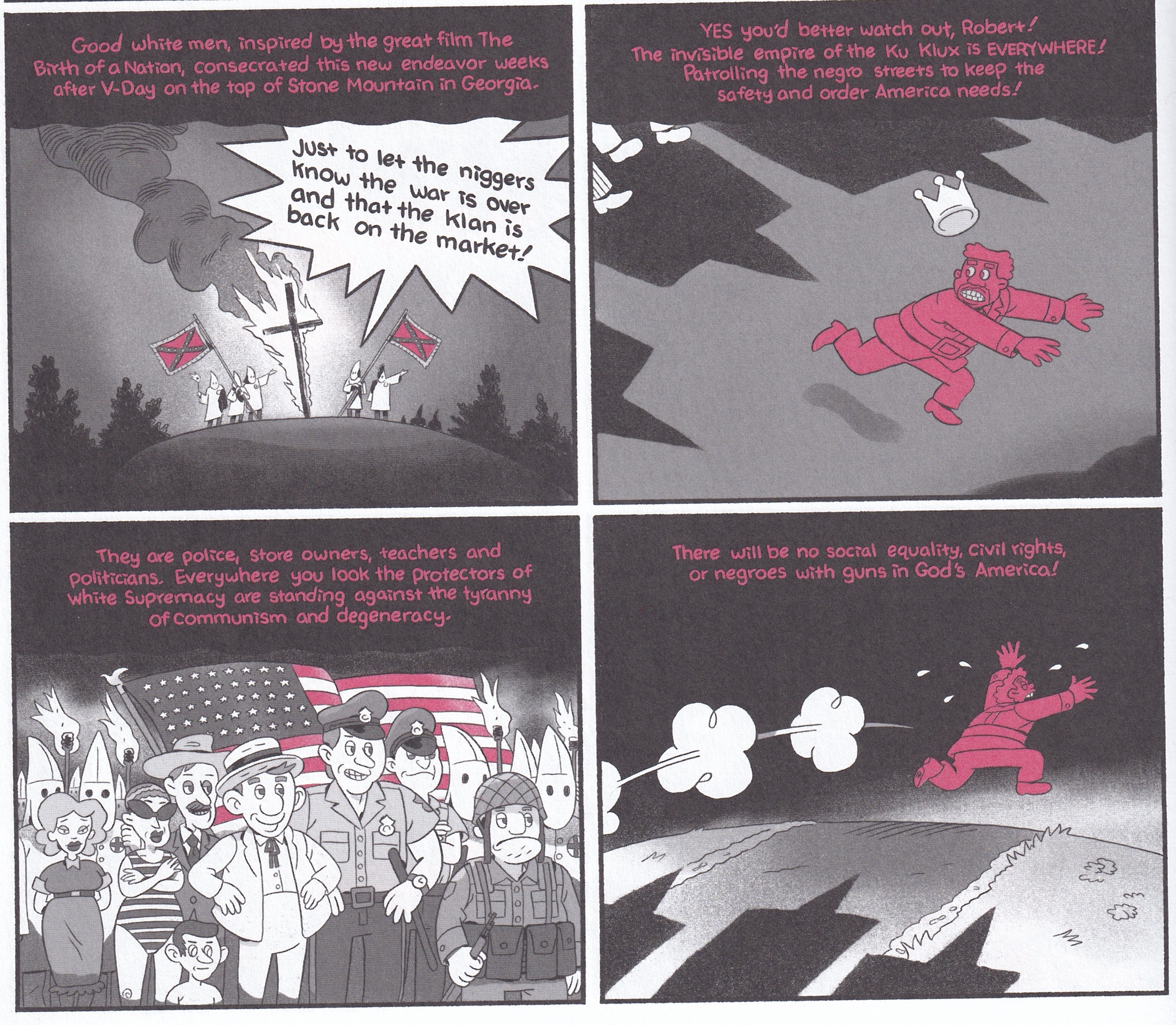

Passmore appears as a time-travelling witness to intensely conflictual, often disregarded, moments in American history: from Robert Charles's police-initiated shoot-out in 1900 to the MOVE commune bombing by Philadelphia police in 1985, followed by a series of uprisings sparked by video footage of police violence as recently as 2020. Along the way he meets both major and minor figures from the Black Liberation struggle.

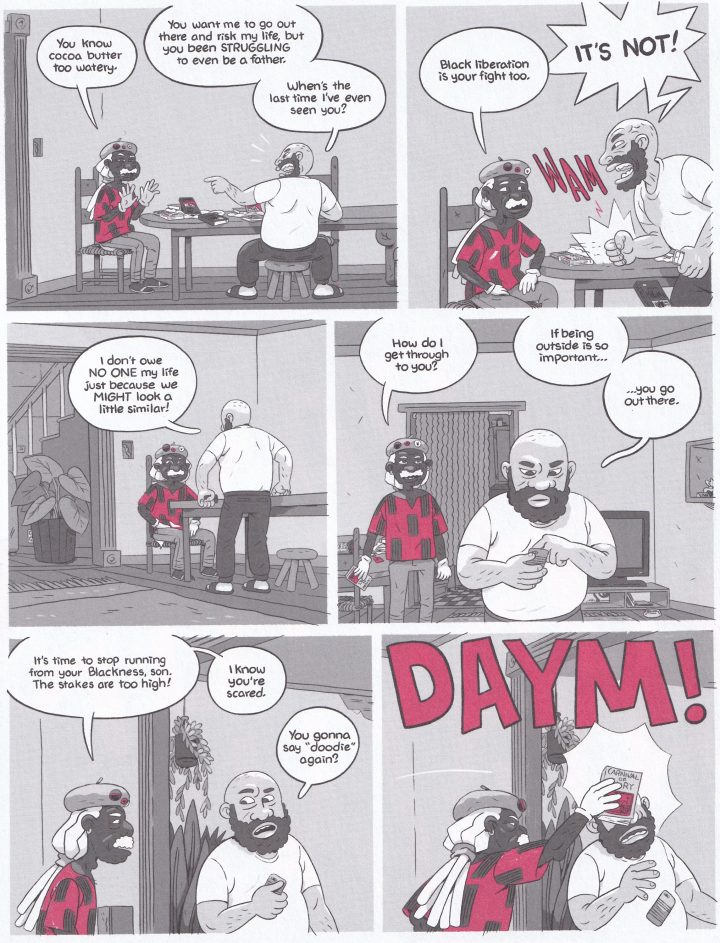

The narrative conceit is that Ben, the character, never quite understands what is going on; so he is constantly being lectured by the past luminaries (as well as a mythical father figure, who urges him toward activism). But my feeling reading the book was that we never hear enough of any one story to quite understand it either, that we don't have sufficient context to grasp what we are seeing on the page. It feels at times like the presentation takes it for granted that we will already know what it is trying to tell us. This assumption leads to some weird narrative choices — giving a lot of attention to Assata Shakur's life before she joined the Black Panthers, for example, but only a couple of pages about her time in the Black Liberation Army and almost nothing about her experiences as a political prisoner and an exile. The book does not so much explain the events it portrays as it briefly reminds us of them, one after another in quick succession. The story thus proceeds with the logic of a dream. In fact, Passmore cries out in one scene, "There's history everywhere, this is a nightmare!"

The narrative conceit is that Ben, the character, never quite understands what is going on; so he is constantly being lectured by the past luminaries (as well as a mythical father figure, who urges him toward activism). But my feeling reading the book was that we never hear enough of any one story to quite understand it either, that we don't have sufficient context to grasp what we are seeing on the page. It feels at times like the presentation takes it for granted that we will already know what it is trying to tell us. This assumption leads to some weird narrative choices — giving a lot of attention to Assata Shakur's life before she joined the Black Panthers, for example, but only a couple of pages about her time in the Black Liberation Army and almost nothing about her experiences as a political prisoner and an exile. The book does not so much explain the events it portrays as it briefly reminds us of them, one after another in quick succession. The story thus proceeds with the logic of a dream. In fact, Passmore cries out in one scene, "There's history everywhere, this is a nightmare!"

Some sections are stronger than others. The dialogue, toward the end, with Sanyika Shakur, an old-school Crip and author of the memoir Monster, is especial powerful. It richly conveys the consequences of a failed revolution, what becomes of the militancy after the political project has collapsed; and, equally, it offers a kind of conversion story, relaying the process by which an individual can acquire a political consciousness and reorient accordingly: "After learning more about Islam from the brother," Shakur recalls, "I overstood it to be a way of life, just like bangin. The god thing never stuck. But he made me think of myself as Black man first, and a Crip second. That was brand-new."

Passmore's linework, at least, is clean throughout, and the art is strangely disarming, even when depicting atrocities. The imagery moves smoothly between literalism and visual metaphor. And the book contains a handful of genuinely inspired compositions, most memorably a line of riot cops whose shadows reveal them to be hooded Klansmen.

Still, the fragmentary narrative, the slippage through time, sometimes makes the connections between events rather obscure, and I was frequently perplexed by the gaps in the story: the missing pieces, the bits left out. Some can be explained as perfectly justifiable choices of scope and emphasis. This accounting begins in 1900, so there is no chapter on slave revolts or Maroon colonies. It is focused on militant resistance specifically; so no mention of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters or the Montgomery Bus Boycott. But then — as one character objects repeatedly in the volume's final section — "where's the Nation of Islam?"

The principle of selection, as well as the strategy of the presentation, are deeply idiosyncratic, as Passmore explains the nature of the overall project:

"To start from the beginning, I gotta admit I've always lived through other people’s eyes. . . . Cause all I knew about being Black was the stereotypes white people put onto me. . . I would’ve went on thinking I was everything white people told me about myself if I hadn’t found something in the back of the schools' library. I found books about Garvey and Black Power, things I had never heard about before that made me feel pride in who I was."

There is a vulnerable, confessional aspect to the speech that is very moving, and at last the purpose of the book becomes clear. Black Arms is less about Black history than about Passmore's relationship to Black history, the use he personally has made of it, the meaning for him as an individual. It is less a history than a personal essay about the importance of history, to spark rather than exhaust our interest.

The post Black Arms to Hold You Up: A History of Black Resistance appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment