“Engineers like to solve problems. If there are no problems handily available, they will create their own problems.” — Scott Adams

Scott Adams, creator of the Dilbert comic strip, creator of controversy, and creator of his own problems, passed away on Jan. 13, 2026, at the age of 68 after a yearlong battle with prostate cancer. Adams’s ex-wife, Shelly Miles, broke news of his passing on a YouTube livestream, sharing a prepared statement in which the late cartoonist expressed gratitude for all the opportunities that had come his way: "I had an amazing life. I gave it everything I had. If you got any benefits from my life, I ask you pay it forward as best you can."

News of his passing was not unexpected, as Adams went public with his cancer diagnosis in May 2025, informing listeners of his Real Coffee with Scott Adams program that the disease had progressed to Stage 4 and that successful treatment was unlikely if not impossible.

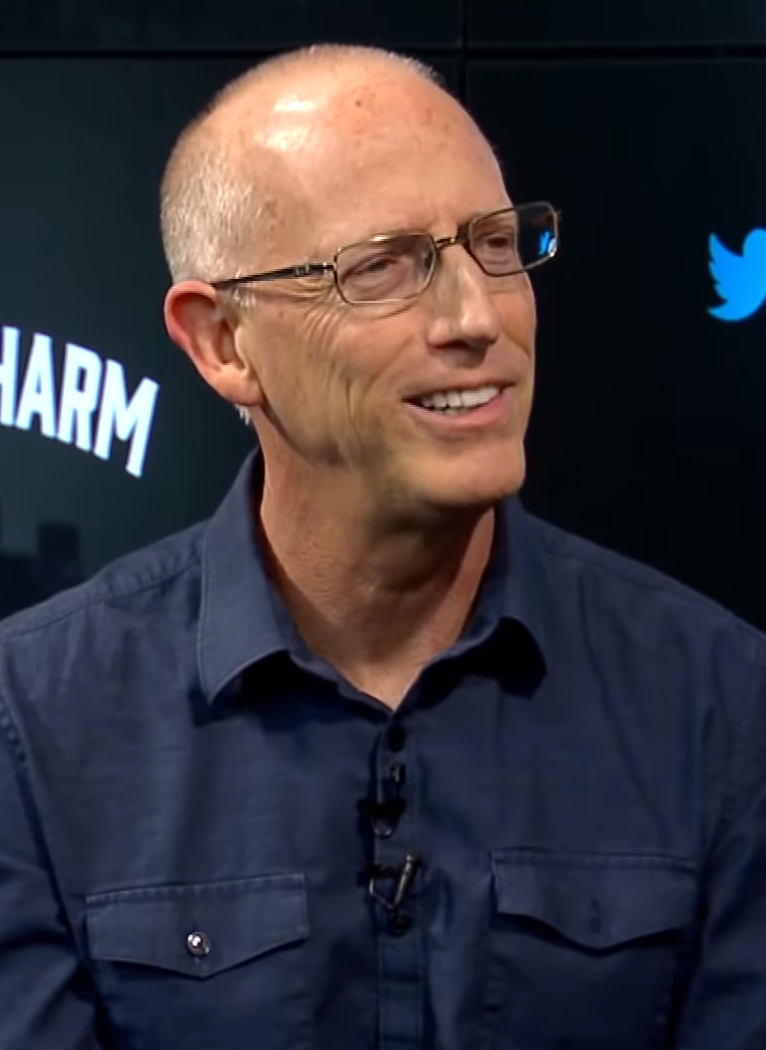

The response to his passing, however, was unexpected to those who knew Adams only as the creator of Dilbert, one of the most successful comic strips of all time. Elon Musk, Fox News commentator Greg Gutfeld, Vice President J.D. Vance and President Donald Trump all offered their public condolences, none of whom mentioned Adams’s career as a best-selling author or award-winning cartoonist, but rather praised him as an influencer and podcaster. The few cartoonists who shared stories about Adams were quick to point out that they hadn’t spoken to him in several years, sometimes several decades, and his former syndicate, publisher, and professional organizations have all declined to pay tribute or even acknowledge his passing.

But years before the term “influencer” came along, Adams was exactly that, and his unlikely path to presidential recognition began on the comics page.

Like many cartoonists, Adams grew up reading newspaper comic strips and dreamed of becoming the next Charles Schulz. Throughout his childhood in Windham, New York, through his college years studying economics at Hartwick College in New York, then as an MBA student at the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley, he was a compulsive doodler, daydreaming about making it big as a cartoonist and crafting a newspaper syndication pitch during his downtime while plugging away at day jobs in banking and telecommunications. “Dilbert was a doodle long before he had a name,” recalled Adams in his 1997 Dilbert compilation Seven Years of Highly Defective People.

“He was a composite of my co-workers at Crocker Bank and later Pacific Bell,” said Adams. “I worked with a lot of technical people and noticed that many of them had potato-shaped bodies and glasses. When I morphed them together in my brain they became Dilbert. I suppose I doodled the technical people more than other people because they seemed more interesting to me, both in personality and appearance.” It was a co-worker, Mike Goodwin, who suggested the character’s name. “The strange thing is that there was a real sense of destiny about that moment. It didn’t feel like Dilbert was being given a name, it’s like I was finding out what his name already was. I can’t explain the feeling exactly, except that I knew it was important even then. It was a rare moment of complete clarity, when I knew I was in exactly the right place at the right time.”

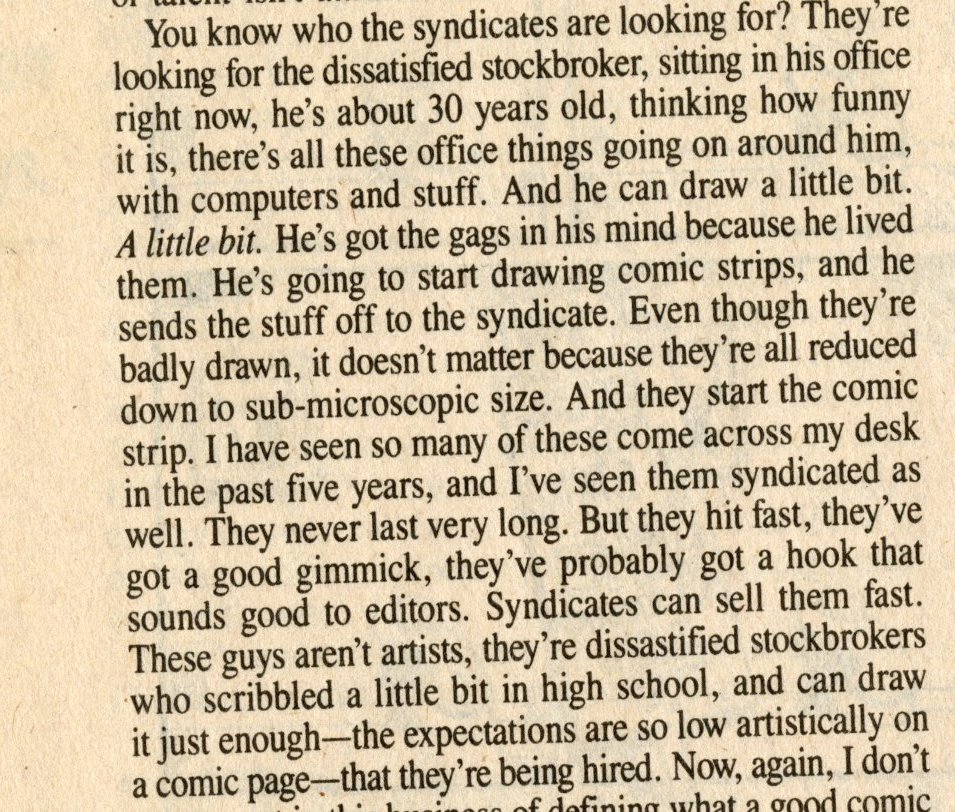

“Exactly the right place at the right time” is an apt description for how Adams landed his syndication deal, as Dilbert checked all the boxes for United Feature Syndicate. In an eerily prescient interview with The Comics Journal in 1988, Bloom County cartoonist Berkeley Breathed predicted the next big trend in newspaper comics. “You know who the syndicates are looking for? They’re looking for the dissatisfied stockbroker, sitting in his office right now, he’s about 30 years old, thinking how funny it is, there’s all these office things going on around him, with computers and stuff. And he can draw a little bit. A little bit. He’s got the gags in his mind because he lived them. He’s going to start drawing comic strips, and he sends the stuff off to the syndicate. Even though they’re badly drawn, it doesn’t matter because they’re all reduced down to sub-microscopic size. And they start the comic strip. I have seen so many of these come across my desk in the past five years…they hit fast, they’ve got a good gimmick, and they’ve probably got a hook that sounds good to editors.”

The following year, Dilbert, not yet an office strip, made its newspaper debut on April 16, 1989, less than six months before Berkeley Breathed retired the daily Bloom County strip to launch the Sundays-only strip Outland. Adams’s strip focusing on the title character, his canine companion Dogbert, and Dilbert’s bizarre science and engineering projects was not an overnight success, but when the strip shifted its focus to Dilbert’s office job and co-workers, Adams found his voice, and circulation of Dilbert grew exponentially, and, ironically enough, was the biggest beneficiary of Bloom County’s departure from daily newspapers. The strip’s office setting gave newspapers the option of running Dilbert in the business section, too, allowing features editors to add the popular new strip without displacing anyone’s favorite from the main comics page.

Readers, especially those working nine-to-five office jobs, related to the blank-eyed, expressionless Dilbert, his nerdy tendencies, and his perpetual frustration and bemusement with his Pointy-Haired Boss, clueless co-workers, and office bureaucracy. It was the perfect clip-and-share strip for cubicle dwellers or anyone who ever felt like the smartest person in the room, an attitude Adams encouraged with collected editions whose titles referred to the people Dilbert encountered as clueless, defective, idiots, and morons.

Adams was arguably the first syndicated cartoonist to realize the potential of the World Wide Web, printing his email address, scottadams@aol.com, in the gutters of the Dilbert comic strip beginning in 1993 and opening a direct line of communication between himself and his readers. Two years later, Dilbert became the first syndicated strip to be published online for free, and Adams created an email newsletter and blog so that he could share his thoughts with readers, and vice versa. Fans were encouraged to share their own office experiences, ensuring that when Adams finally left his day job at Pacific Bell in 1995 that he would stay connected to the contemporary workplace and the booming dot-com economy, culture, and jargon that would inform the strip in the years to come.

Fans who followed Adams were also treated to an inside look at the creation of the strip, director’s commentary, and Easter eggs unavailable to those who only read Dilbert in their daily newspaper. When Dilbert was ready to take his relationship with his girlfriend Liz to the next level, Adams tipped off his newsletter audience that his trademark curved red-and-black necktie would be drawn flat the day after Dilbert “lost his innocence” with Liz, neatly bypassing the content restrictions of the family newspaper while building an insider’s clubhouse for his most dedicated fans.

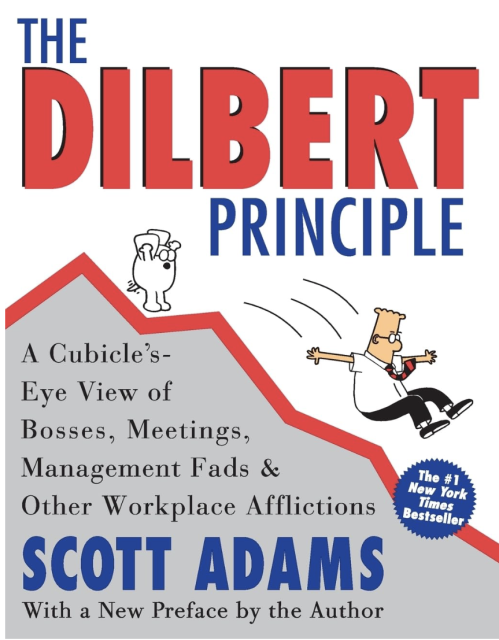

And there were many dedicated fans. Within five years of launch, Dilbert was carried by more than a thousand newspapers worldwide, and the best-selling strip collections published by Andrews-McMeel generated millions of dollars of revenue for Adams and his publisher. His first business guide, The Dilbert Principle, built around his theory that "the most ineffective workers are systematically moved to the place where they can do the least amount of damage" would sell over a million copies for publisher HarperCollins and would land on the New York Times Best Sellers list for 43 weeks from 1996 to 1997, earning Dilbert (but not Adams) a spot on Time Magazine’s most influential Americans list in 1997 and made him the face of a $30 million advertising campaign for Office Depot.

In addition to mainstream and financial success, Adams was recognized by his peers and honored with the National Cartoonists Society’s most prestigious award, the Reuben, as the outstanding cartoonist of the year for 1997. Any reservations that the NCS membership had about recognizing the cartooning skills of someone who readily acknowledged the simplicity and overall crudity of his own artwork fell by the wayside as Adams’s career and readership soared. He could be standoffish and brusque with fans and even his fellow cartoonists, especially if he felt they were trying to take advantage of his success, but many colleagues recalled Adams as generous with his time and encouragement, especially to up and coming creators. “I’m a cartoonist because of Scott Adams,” said Jon “Bean” Hastings in a January 13 Facebook post. “I did the lettering on Dilbert for six years in the early 90’s, beginning a fortuitous two weeks after I started Kiwi Studios. Scott paid me close to a full-time wage for a very part-time job — about an hour a day — freeing me to scribble up my own comics, while doing other freelance work as well.

“As technology advanced through the '90s, he could have easily switched over to computer lettering, but I think he kept me around because he liked supporting a goofball fellow artist. In fact, when he finally did let me go, he gave me a stunning $3,000 bonus.”

Stephan Pastis, another Northern California cartoonist, also acknowledged Adams’s early, enthusiastic support as instrumental in his own success with his syndicated comic strip Pearls Before Swine. “Scott Adams is the whole reason I have a career. Years ago, he endorsed my strip to millions of his readers and that was my big break.” Pastis, it should be noted, also had a lucrative day job while working on his syndication pitch and dreaming of life as a full-time comic strip artist.

Newspaper and magazine articles and interviews with Adams were inescapable throughout the 1990s, and he became such a public figure that mainstream audiences recognized the bespectacled cartoonist when he made cameo appearances on NBC’s NewsRadio and the syndicated sci-fi series Babylon 5. Even more best-selling books followed, and merchandise ranging from the expected coffee mugs, Hallmark cards and desktop calendars to breath-freshening Manage-Mints and the vegetarian microwaveable Dilberito (accompanied by a flash-animated video game) further established Dilbert as the biggest breakout strip to hit newspapers since Garfield. Dilbert was also the first comic strip since Garfield to reach the 2,000-newspaper mark in syndication, and, due to the ever-decreasing number of active newspapers, is the final strip that reached that benchmark.

Dilbert was so popular and influential during this era that, after several near-misses, a Dilbert animated series debuted on UPN in January 1999. Larry Charles, fresh off of Seinfeld, co-developed the series with Adams, and A-list talent from The Simpsons and Seinfeld joined a voice cast led by Daniel Stern as Dilbert, Chris Elliott as Dogbert, Kathy Griffin as Alice, and Larry Miller as Pointy-Haired Boss. The series was a moderate hit for UPN, earning an Emmy Award for Outstanding Title Design (the theme for the show was composed by Danny Elfman), but diminishing ratings and the network’s decision to focus on live-action programming led to its cancellation at the end of the second season.

"Scott was a very brilliant but very apolitical fellow in those days,” said Larry Charles in an Instagram post. “We wrote or rewrote all the scripts via email and had a good relationship. I thought of the show as more science fiction than an office comedy and we explored many futuristic themes like what is the role of technology and what does it mean to be human. It was fun to produce. It only lasted two seasons, which was perfect. He was so successful and lived in the proverbial bubble that I believe after the show ended it led to his hubristic somewhat arrogant pronouncements which won him new but dubious fans and lost him many more. His humor was always dry and hyperbolic and he didn’t care if people got it or not or what the consequences might be."

The cancellation of his television series–and the Dilberito’s failure to revolutionize the office lunchroom experience–was relatively minor for Adams, whose daily comic strip and book sales were as strong as ever in the early 2000s. Public speaking engagements, interviews, and regular features on local and cable news shows kept him in the spotlight, and his newsletter and blog allowed him to share his non-Dilbert thoughts and opinions directly with a captive audience. With each new social media platform that came along, Adams was an early adopter, embracing every opportunity to expand his reach and share his worldview.

Adams spoke candidly about expected topics like cartooning, office culture, and popular entertainment, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, revealed his self-described “Libertarian leanings” as he ventured into discussions of current events and politics. Controversial and outright hateful comments were framed as “thought experiments,” such as a 2006 Dilbert Blog post that questioned historical accounts of the Holocaust or a 2011 post in which he compared adult women to “children and the mentally handicapped.” Adams offered dating advice that included “pickup artist” techniques and emotional manipulation, but the Dilbert comic strip plugged along as usual, just with more dot-com jokes and cynical takes on the economy in the wake of the 2008 crash. Most daily newspaper readers and feature editors were oblivious or indifferent to Adams and his online activity, and friends chalked up the occasional offensive newsletter or blog post to the cartoonist’s sense of humor or desire to provoke a reaction. He had been happily married since 2006, after all, and was a devoted stepfather to two children, so how much of a jerk could he really be?

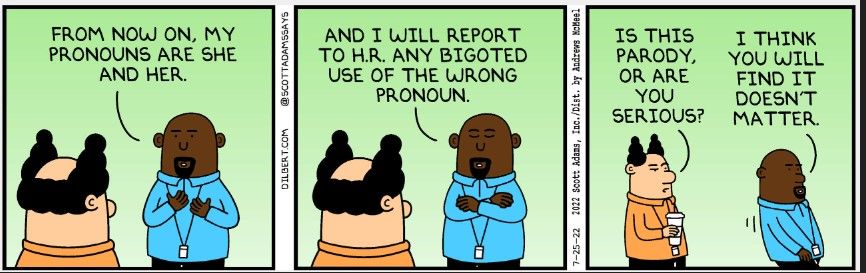

Readers, especially in hindsight, felt that Dilbert’s tone shifted during the 2010s, punching down at targets, mocking and belittling societal shifts and perceived “political correctness,” with more cynical, even bitter humor than the bemused, gentle office hijinks of the strip’s first two decades. “Dilbert went from challenging the absurdities of workplace management and the abuses of late-stage capitalism to a broader distrust of all expertise, media, and institutions,” observed Rob Salkowitz in his Adams obituary for Forbes.com. “The tone became combative, the humor more hectoring. Dogbert, Dilbert’s anarchic pet who always managed to come out on top, began delivering preachy monologues more suited to the op-ed page.”

Adams and Shelly Miles divorced in 2014, with an amicable split; Miles moved to another home just a block away following their separation. Dilbert and Adams’s blog, supplemented by a near-constant presence on Twitter, changed little after the dissolution of his marriage. His online presence continued to mix amusing observations with intentionally provocative Tweets, and he seemed to revel in being an internet troll.

When Donald Trump announced his Presidential candidacy in June 2015, Adams became an early and vocal supporter of the real estate developer turned reality television star. Throughout the next year and in the weeks leading up to the election, Adams was one of the most prominent public figures willing to go on record predicting a Trump victory when nearly every major poll and pundit suggested otherwise. As a guest on HBO’s Real Time with Bill Maher in May 2016, he projected Trump’s odds for victory at 98%, a figure that he invented based on pundit Nate Silver’s then-recent prediction that the candidate only had a 2% chance of winning the presidency. In the solicitation for his best-selling book on the 2016 election, Win Bigly: Persuasion in a World Where Facts Don’t Matter, Adams insisted that the candidate had “a level of persuasion you only see once in a generation. We’re hardwired to respond to emotion, not reason, and Trump knew exactly which emotional buttons to push.”

In the aftermath of the election, Adams became a fixture on cable news programs, parlaying his successful prediction into a side-hustle as a political pundit. His public support for many of Trump’s social and economic policies had a negative impact on his social life but not immediately on his career, as the majority of Adams’s clients supported his right to free speech and his support of the political party of his choice. In 2018, midway through Trump’s first term, he launched a Periscope podcast that served as an unfiltered platform for his social and political opinions, which became increasingly conservative and right-wing.

That year, Adams experienced his first significant political backlash. In the wake of a mass shooting in Highland Park, he opined on social media that a parent is obligated to kill their own child if he is “a danger to himself and others.” Connecting the shooting to his stepson’s recent death from a fentanyl overdose, he wrote, “This won’t be easy to read. When a young male (let’s say 14 to 19) is a danger to himself and others, society gives the supporting family two options: 1. Watch people die. 2. Kill your own son. Those are your only options. I chose #1 and watched my stepson die. I was relieved he took no one else with him.” These comments were seen as tough love by some online fans, but were deeply troubling to friends and family who were concerned about Adams’s mental health.

And the floodgates were open. In 2020, he took to Twitter to claim that the Dilbert animated series was the "third job I lost for being white," citing UPN’s decision to create more content by and for Black people as the reason for his series’ cancellation. On the podcast Real Talk with Zuby, he made an unsubstantiated claim that he had been a victim of “reverse racism” at Crocker Bank, and left after being told by management that “we cannot promote white males anymore. I was finishing my MBA and they promoted my co-worker who only had a high school education.” Judging from context, Pacific Bell would seem to be the third job Adams believed he lost for being white, but all accounts at the time suggest that he left on his own terms due to the success of Dilbert.

In the buildup to the 2020 presidential election, Adams took to Twitter to warn that “Republicans will be hunted” and that “there’s a good chance you will be dead within the year” if Joe Biden won the election. These Tweets were typical of Adams’s public persona by that time. His punditry alienated many fans of his comic while cultivating a very specific political audience. His YouTube channel grew to nearly 200,000 subscribers and his Twitter account acquired over one million followers, making him one of the most popular and influential users of the social media platform. His online presence became increasingly provocative and inflammatory during the Covid era, as he complained about lockdowns, mask mandates, vaccines, and the Democratic Party to a diehard audience with a similar outlook. Another major change for Adams in 2020 was his marriage to pilot, influencer, and former child model Kristina Basham, who was born the year before Dilbert made its newspaper debut. Citing “a tough pandemic,” they separated and divorced less than two years later.

Adams was certain that his outspoken political beliefs and his criticism of “wokeness” caused Lee Enterprises to drop Dilbert from its network of nearly 80 newspapers in 2022, a substantial hit to his syndication income. Characteristically, he doubled down on his provocateur status. In February 2023, in reference to a Rasmussen Reports survey on race that asked people if they agreed with the statement, “it’s OK to be white,” Adams noted that only 53% of Black respondents had agreed with that declaration, which he found completely unacceptable. He called Black people “a hate group” and said “the best advice I would give to white people is to get the hell away from Black people; just get the fuck away.”

Dozens of newspapers dropped Dilbert immediately, with some running a blank space on the comics page, others using that spot to run a statement from the features editor explaining the decision to remove Dilbert from the newspaper, and others taking the opportunity to replace Adams’s comic with another strip created by a woman or person of color. Over the course of the weekend, Adams’s syndicate, Andrews McMeel Universal, severed ties with him and canceled his contract. Dilbert was dropped from its 1,400 remaining newspapers overnight. "As a media and communications company, AMU values free speech," read the syndicate’s official statement on the matter. "But we will never support any commentary rooted in discrimination or hate."

Adams received support from then-Twitter CEO Elon Musk, who claimed that the media previously “was racist against non-white people, now they’re racist against whites & Asians.” Other rightwing news outlets blamed reverse racism and cancel culture on Dilbert’s departure, while the cartoonist declared himself a victim of CRT (Critical Race Theory), ESG (environmental, social and governance), and DEI (Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. "If you look into the context, the point that got me cancelled is that CRT, DEI and ESG all have in common the framing that White Americans are historically the oppressors and Black Americans have been oppressed, and it continues to this day,” Adams said in the aftermath of his newspaper cancelation. “I recommended staying away from any group of Americans that identifies your group as the bad guys, because that puts a target on your back."

Adams took advantage of the publicity surrounding his cancellation to launch the subscription-based Dilbert Reborn and a podcast called Coffee with Scott Adams, which would soon grow to nearly 200,000 subscribers on YouTube. Having been dropped by his literary agent, Adams self-published a series of eBooks and found an audience of MAGA and Trump supporters more than willing to patronize his “anti-woke” vision of Dilbert. Public speaking appearances and invitations to appear on cable news programs dropped off completely, but Adams was free to be as belligerent and outspoken as he pleased for an audience that was more than happy to indulge him.

Scott Adams made headlines once again in May 2025, when he immediately followed up news of Joe Biden’s cancer diagnosis with the revelation that he had been diagnosed with Stage 4 prostate cancer that had spread to his bones and had weakened him to the point that he could no longer walk unassisted. In a video filmed at his home, the cartoonist revealed that he had declined the established medical treatments for prostate cancer and had instead opted for alternative methods including the anti-parasitic medication fenbendazole and horse dewormer ivermectin. This approach proved ineffective, and Adams announced that he did not expect to live through the summer.

In early November, Adams was still alive, but his health had taken a severe decline, with the cancer spreading unchecked throughout his bones and the rest of his body, leaving him bedridden and in constant pain. He appealed to Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. on Twitter, asking him to intervene on his behalf to fast-track his treatment with the FDA-approved cancer drug Pluvicto, after difficulty scheduling the treatment through his healthcare provider. Kennedy issued the immediate reply “On it!”, followed up with a post asking, “Scott, how do I reach you? The President wants to help.”

Subsequent messages from Adams make it unclear if his medical team was able to provide Pluvicto or if the supposed “miracle drug” would have provided any relief for his advanced condition, which had left him paralyzed from the waist down. He marked the new year with a livestream update on Real Coffee with Scott Adams, informing his audience “It’s all bad news. The odds of me recovering are essentially zero. I’ll give you any updates if that changes, but it won’t,” noting that January would be “a month of transition.” Just over a week later, he entered hospice care at his Pleasanton, California home, and passed away on January 13.

News of his death elicited mixed reactions online, with relative silence and mild, qualified praise from his colleagues, cheers and mockery from those still embittered over his hurtful and hateful commentary during the final decade of his life, empathy from those saddened by his rapid decline in health if not his rapid fall from grace, and tributes from Donald Trump’s White House, including a disturbing AI-generated illustration of J.D. Vance, Donald Trump, and Dilbert, each rendered with a vacant stare and large, toothy smile, despite the fact that Adams had deliberately designed his character with no visible mouth. If Donald Trump was aware of Adams’s pre-podcast career, his dashed-off Truth Social post gives no indication that he did. "He bravely fought a long battle against a terrible disease. My condolences go out to his family, and all of his many friends and listeners," one final, bitter punchline for Dilbert.

The post I have no mouth and I must scream at Black people: Scott Adams, 1957-2026 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment