Two decades ago, Brian Sendelbach did a series of subversive, brain-twisting comics under the guise of “Smell of Steve, Inc.” Among them was (and I may have the title wrong) “The Laughing Disease,” in which the nation is struck by a viral infection that makes its victims guffaw themselves to death. A solution is discovered. An official instructs the nation to open their Sunday newspaper and read Beetle Bailey. All at once, the plague is vanquished; the last laugh dies off.

This summed up where Mort Walker’s work was in the 1990s. Predictable at every turn, its inspiration succumbed to formula, Beetle Bailey was an institution. Alongside Charles Schulz’s Peanuts, which also debuted in 1950, Walker’s strips dominated the syndication market thereafter.

Peanuts of 1995 was a faint shadow of its former self, but it still compelled its large readership. Schulz’s ink lines showed a palsy that made the strip feel like something its creator did with great physical effort and focus. Its readers remembered the vibrancy of the 1960s and ‘70s, when Peanuts was a reason to buy the paper every day. It mattered to our society. Those who stayed with the strip to its end held a loving devotion to an important cartoonist; they forgave its diminished state and were glad it remained.

Beetle of 1995 was a fly in amber. A reduction of linear and verbal detail that marked the passing of time as its cast, themes, gags and trends auto-piloted their way through days, weeks, months, years, decades. I presume it still had its fans — those who turned to the comics page, eager for a laugh, and were rewarded. Oh, that Zero! Such a lovable goof … ooh, Sarge has pounded Beetle into a pulp. Again. When will that boy learn?

My indifference to Mort Walker’s work was countered by the discovery of his self-referential side project Sam and Silo/Sam’s Strip, which had a quirky wit, a deep trove of comics history and a playful vibe that was a world away from Bailey’s mechanical game. In my research work on other newspaper cartoonists, I came across many early examples of Beetle; they were — I don’t know how else to put it — funny. Full of visual detail, composed of many words, they read as though their creator cared to make them worth the reader’s time and effort.

Mort Walker entered the syndication world at mid-century, with a fan’s glee and a young man’s energy. He drew funny in the mid-century magazine cartoon style: bulbous noses, bread-loaf feet, coat-hanger elbows and knees — each posture of each character full of life and personality. He understood the oft-brutal process comic strip art suffered in its path from Bristol board to newsprint. Our daily papers were dashed off on high-speed presses, where dislocated colors or under-inked blacks weren’t heeded by the men who worked the machinery. Bold, direct shapes that read well and printed without undue damage helped make Beetle one of the high-visibility strips in newspapers.

Newspaper comics’ decline began with size reduction during the second World War. Newsprint was rationed and recycling was encouraged. With few exceptions, former full-page Sunday strips went to half or third pages. Some newspapers, like the St. Louis, Missouri Post-Dispatch, reduced their Sunday comic-strips to fourth, fifth and sixth pages; they chopped and stacked panels and crammed as many features as one page could hold.

Daily comics, once published in five or six-column widths, halved that luxurious size as their hold on the public waned. In the first half of the 20th century, comics were a selling point of newspapers. All age groups and social classes read and enjoyed them. The acquisition of Blondie or Dick Tracy in your local paper was ballyhooed. Hefty Sunday papers were wrapped in their color comics section; its arrival made a grand thud on doorsteps. Comics made a difference. Adults read them with glee; kids laid wall-eyed on their living-room floors, pages spread open as they took in the color and imagery.

They were also disposable, like the rest of the daily paper; only oddballs saved them. Many of those people, like Walker, became professional cartoonists. Their work, influenced by the material they absorbed in their youth, kept the flame alive and added something new to the mix.

It took Peanuts a few years to win a wide audience. I find the first several years of the strip fascinating. Its bleak, sarcastic vibe must have felt shocking and unsettling in the first half of the ‘50s. Walker’s work always aimed to please the mass audience. Peanuts gave the reader pause; Beetle Bailey induced the ideal boffo laff, like Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy.

Walker did so with a high level of craftsmanship and polish. He went further in the strip’s first decade. He often surprised the reader’s expectations; he had room to do so. At a third or half page in the Sunday paper, Beetle could woo his reader with enough visual and verbal detail to tee up a point, hit it home and always leave ‘em laughing.

Mort Walker's Beetle Bailey: 75 Years of Smiles, a new full-color hardcover published by Fantagraphics and written and edited by Brian Walker, threw down a gauntlet to my jaundiced view of this iconic comic strip. A decade-by-decade tour of a beloved institution, it reveals that the first two decades (a period when newspaper comics got a second wind and still had some clout) are better than I imagined.

In contrast, New York Review Comics has reissued the playful 1980 treatise Lexicon of Comicana, also edited by Brian Walker and with an introduction by Chris Ware. This slim volume teems with the gleeful play that made Sam’s Strip a creative high point in a conventional career. Both books show that there was once a creative fire in Mort Walker’s work. It ebbed with newspaper comics’ lost influence. By the 1970s, with the exception of G. B. Trudeau’s Doonesbury, which gained an immediate, faithful audience, the legacy strips were on life support. Walt Kelly, Roy Crane, Gus Arriola, Al Capp, Milton Caniff and Chester Gould still produced work, but most strips had outlived their creators and were continued by assistants or ghosts. Editors shrank the comics further — perhaps to alienate their audience and provide an excuse to get rid of them.

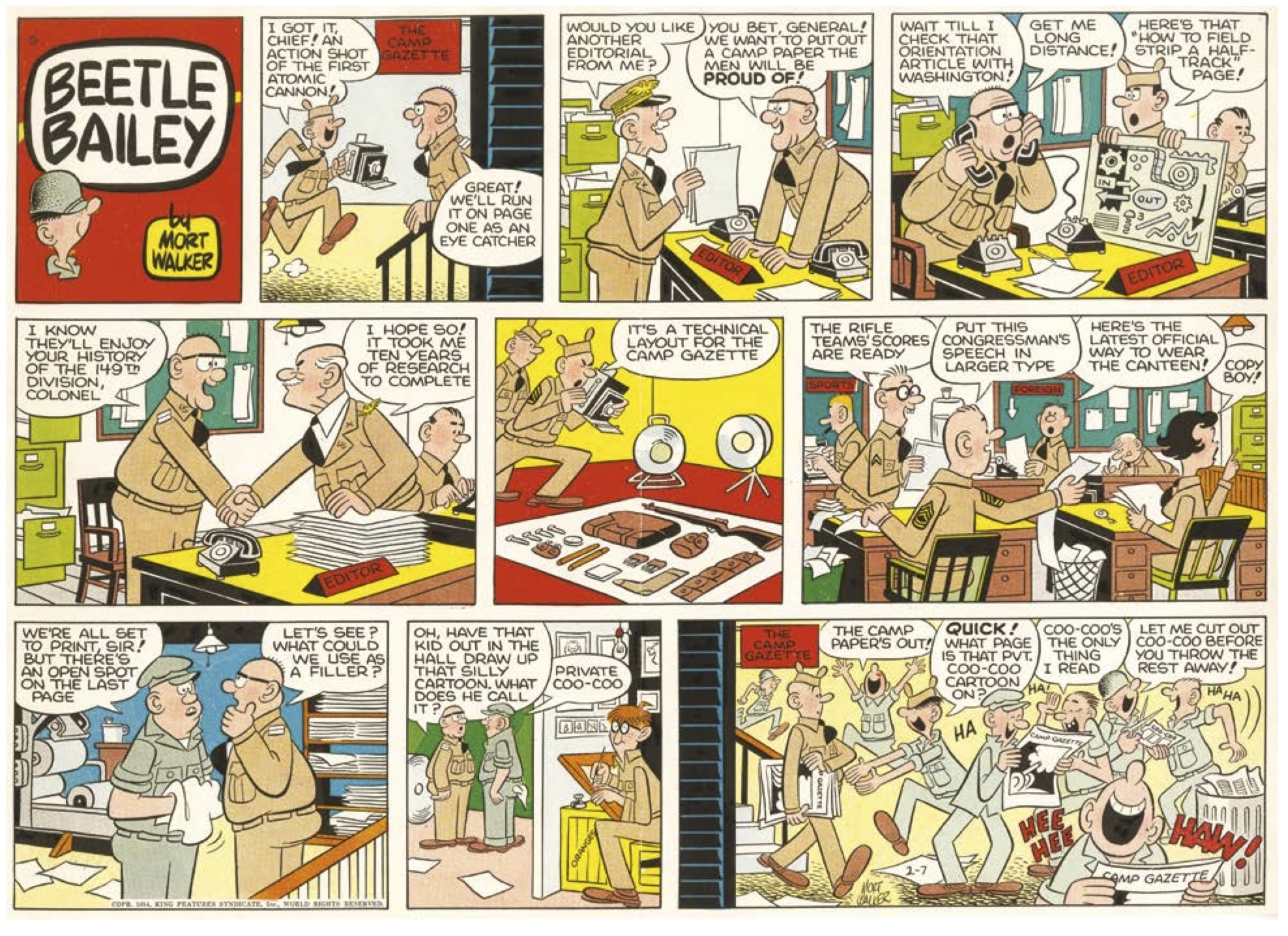

The first decade of Beetle, done before the worst post-war cuts sunk in, are a revelation. Walker’s skill for comedic escalation is impressive and amusing. The Sunday strip for Feb. 7, 1954 can serve as Exhibit A. In 199 words, spread over nine panels, it follows the progress of an issue of the Camp Swampy newspaper. Editors coordinate with writers, artists and photographers; the head editor proclaims that “we want to put out a camp paper that the men will be PROUD OF!”

Come press time, a hole in a page is discovered. The harried ed has the staff cartoonist knock off a comic strip to fill the gap. The paper goes to press and hits the camp. All the GIs care about is that comic strip — a work beneath the contempt of the editors, whose articles, editorials and instructional pieces, for all their effort and good intent, are ignored.

Many steps set up the strip’s payoff. The first six panels document the hustle and chaos of any newsroom. We get a quick portrait of the nameless editor — we see his ambitions, hard work and TLC; his diplomacy with Army brass; his belief that he’s doing something of value to the military. That a rogue, dashed-off doodle connects with the soldiers is a delightful outcome: comics for the win! We see how conflicting priorities collide. The moral of this story: one man’s lofty goals line others’ wastebaskets.

Walker draws each panel in a medium or long shot, with enough detail to evoke a sense of place and pace. Urgency embodies the paper’s staff as they rush against a deadline. To those who know the current iteration of Beetle, this 1954 strip might not be recognizable. Its events aren’t generic situations for time-worn characters. We get a sense of a larger world, within the perimeters of the army camp, and no one is the focus of what occurs.

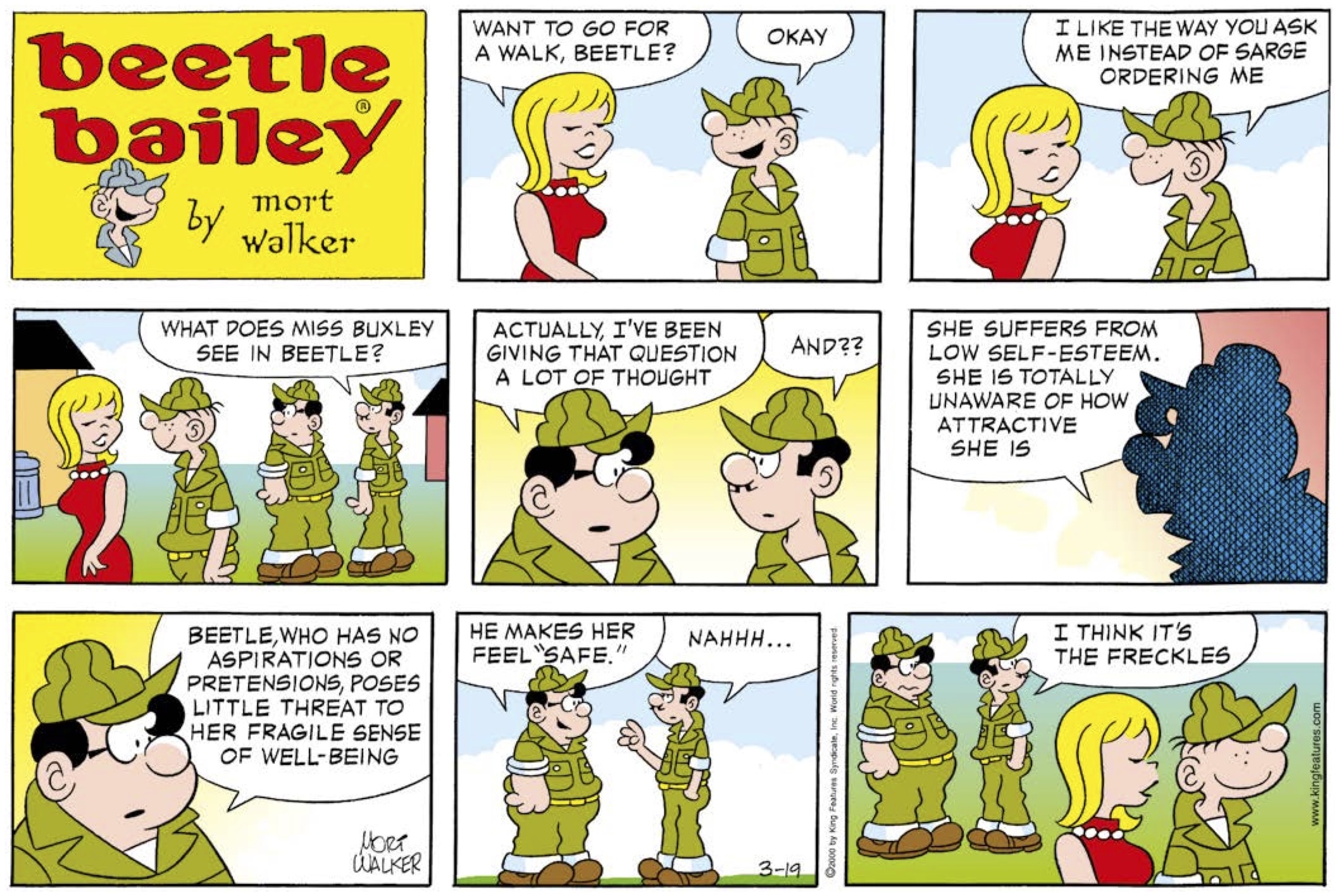

Exhibit B: the Sunday strip of March 19, 2000, contains 81 words (lettered at twice the size of the ’54 episode). There is no background detail beyond two simple building shapes, and more close-ups or two-shots than medium or long. This episode takes one-fourth the time to read, and though the character of the well-read Plato orates much of it, nothing really happens. Its punchline is a mild observation. No crisis, action or reaction has occurred. Stasis triumphs.

These two episodes demonstrate the decline of the American newspaper comic strip. Once teeming with detail and dialogue and given a canvas of half a page (which it well exploits), Bailey is bereft of texture, character and substance by the dawn of a new century. This was not Mort Walker’s fault; he adapted his work to survive in less space, little editorial disregard and minimal importance to the newspaper’s well-being.

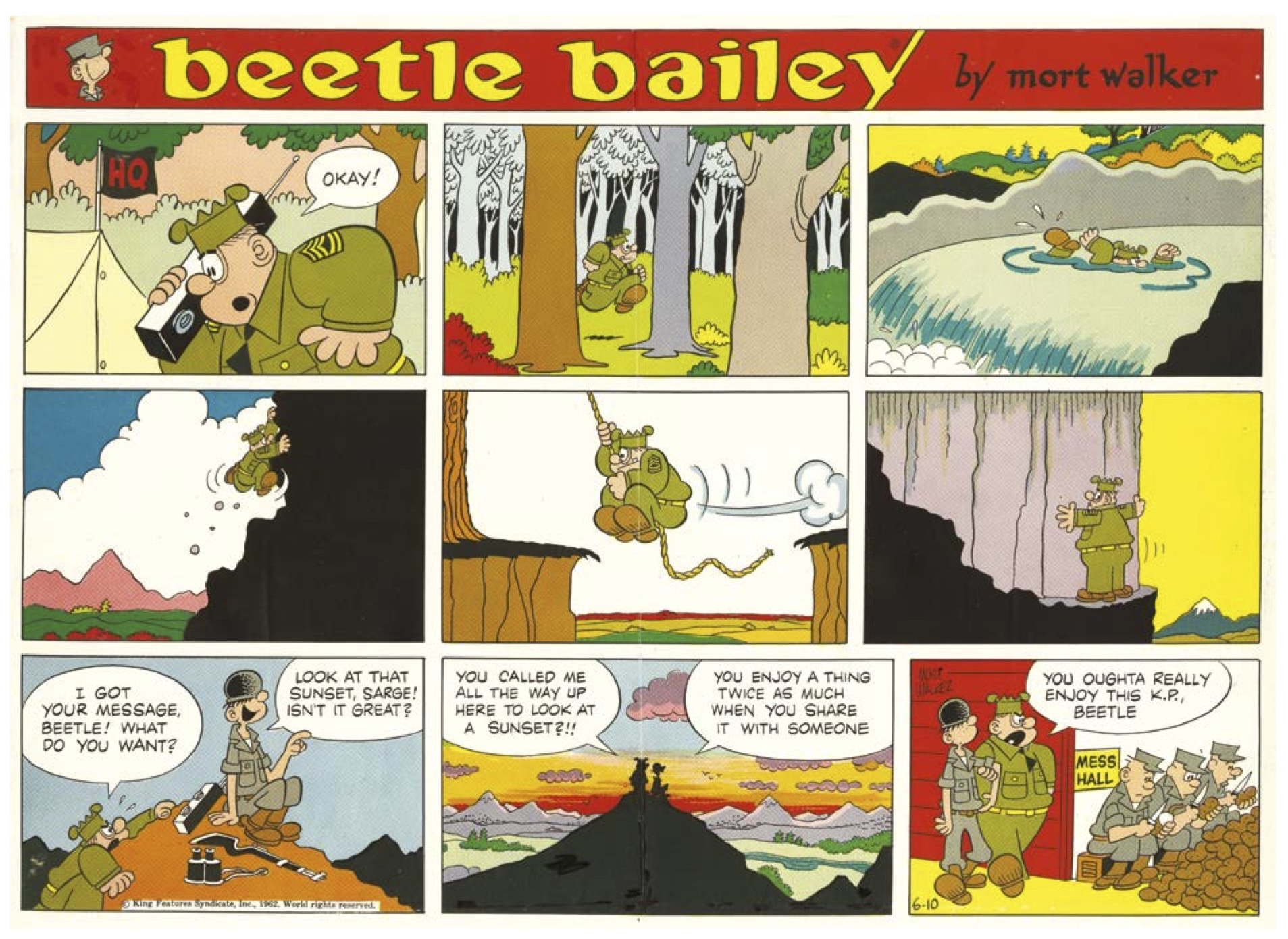

The strip wasn’t wordy by nature. Walker admired the pantomime approach of earlier cartoonists and understood that an image speaks for itself. The Sunday episode of June 10, 1962, takes place outdoors. A variety of natural backdrops underscore a quiet but affecting look at opposing priorities. The last panel offers a "kicker" that undercuts the sentimental moment before it. Had Walker created this episode 30 years later, the last panel wouldn’t be there, and the stylized visuals would be less complex and engrossing.

The military wasn’t happy with Beetle Bailey in the 1950s; they felt it took potshots at their dignity and traditions. Walker used his experiences during the Second World War for inspiration. Under more stressful conditions, he’d seen how the hierarchy of the Army worked — as had Nat Hiken, whose classic TV sitcom You’ll Never Get Rich (AKA Sgt. Bilko) took a harsher stance against military protocol. Hiken served in the Army Air Force during WWII, and his was a jaundiced view. I imagine the character of the amoral scofflaw Ernest Bilko (played to perfection by Phil Silvers) gave military brass nightmares. Small wonder that, in the final episode of the long-running series, Bilko was court-martialed; five years of swindles, disregard for the rule of law, and of his superiors had to be punished.

Walker’s well-aimed swipes at military foibles softened through the 1960s. By then, Bailey’s cast did less real-world Army things. They were characters gathered in a neutral container where their quirks became fodder for comedy. Walker expanded the strip’s cast; farm boy Zero and philosopher Plato gave him more personalities to riff upon. Zero’s naïve ways were frequent feedstuff; Plato’s discourses became a recurrent theme in the Sunday episodes.

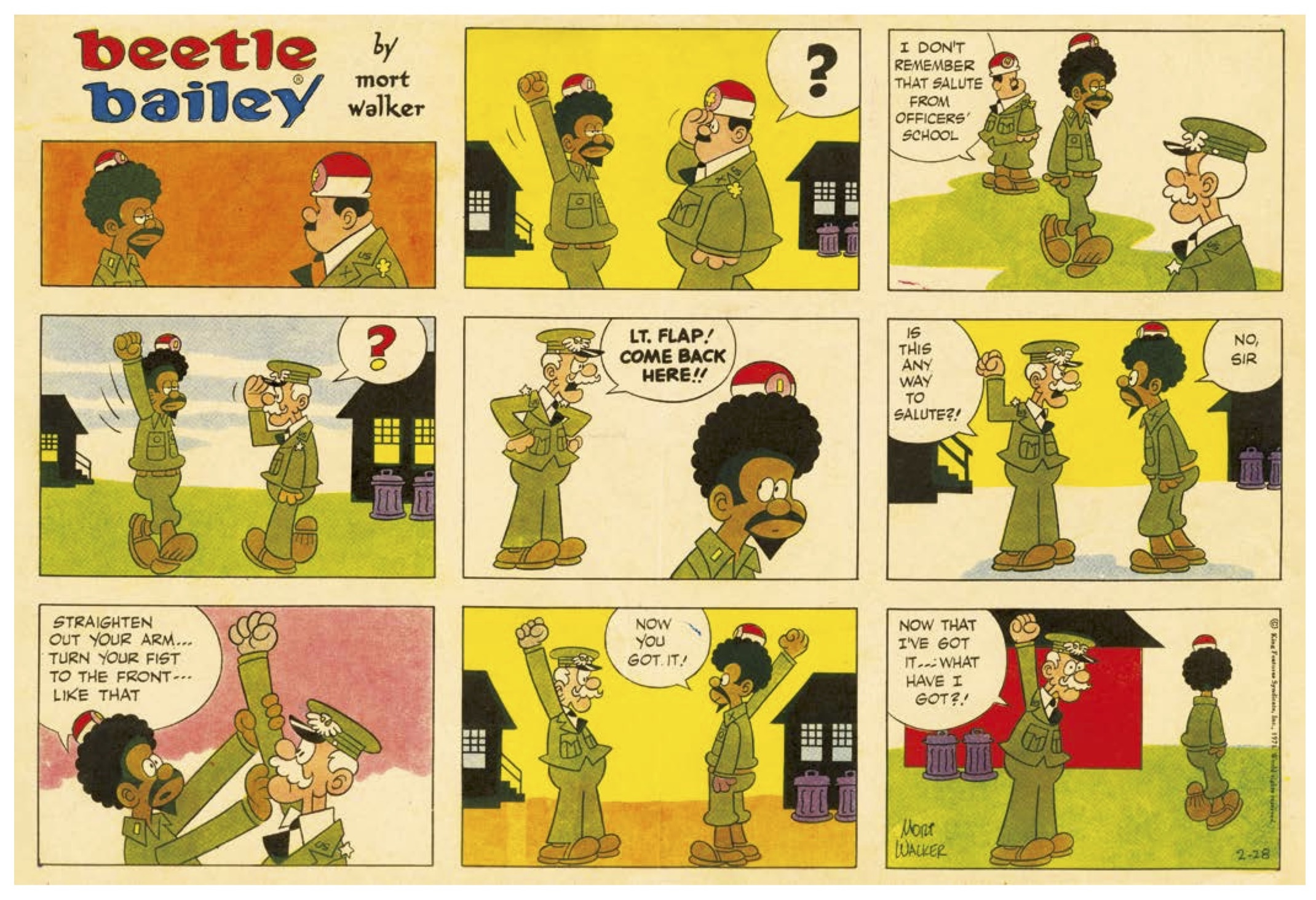

Black officer Lt. Flap debuted in 1970, at a time when non-white figures began to populate pop culture in earnest. Walker mined some daring moments with Flap, as in the episode of

Flap’s ethnicity soon became moot. Like Rocky, Zero, Otto, the Chaplain and General Halftrack, the strip’s cast became chess pieces in a well-worn game; move one toward another and something will happen. The endgame was no longer the long play of the 1950s and ‘60s material, but a simple situation with a broad payoff: a quick laugh and nothing more.

By the start of the 1980s, most Sunday comic strips appeared in quarter-page editions; the dailies seldom exceeded one-third of a page’s width. There wasn’t enough real estate for a cartoonist to say or do much. Yet many career cartoonists soldiered on.

Beetle Bailey made Mort Walker a wealthy man; he put some of this to grand use in the establishment of the International Museum of Cartoon Art in 1974. He sought to legitimize cartooning and pay tribute to the artists who inspired him — and to cast a light on newer cartoonists from all over the world whose presence hadn’t pervaded America. This noble enterprise was a meaningful act to keep the legacy of cartoonists’ work alive and available.

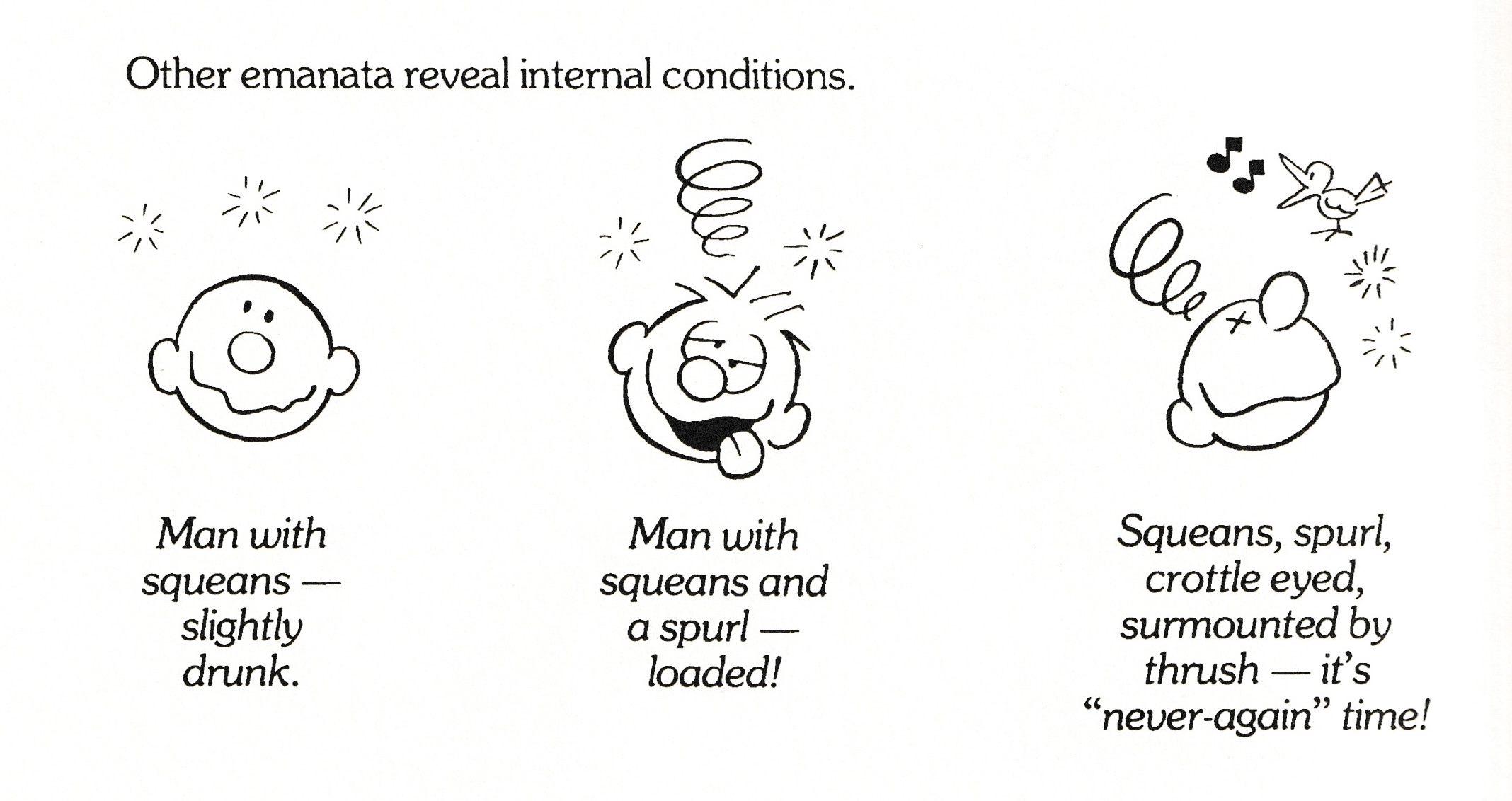

As Walker regarded the work he’d admired in his childhood, he might have given a wistful sigh; where did it go wrong? Small wonder he engaged in this large project and other smaller ones. Among those was The Lexicon of Comicana. Here, the quick wit, observational humor and free association that Beetle no longer housed comes into play. Walker and his colleagues had, over the years, given names to elemental tics of cartooning. Sweat drops that flew from a character’s head were plewds; the classic lightbulb-over-the-head, emanata. An intoxicated figure radiates squeans, spurls and, if soused enough to have a chirping bird overhead, thrush.

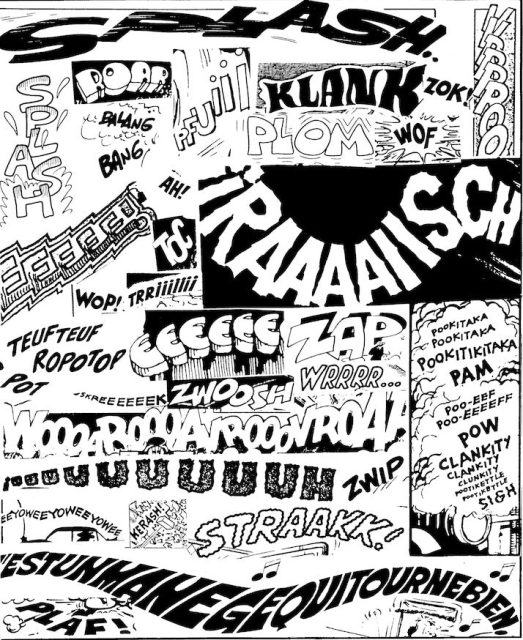

This is done with tongue in cheek; it also gives these icons of cartoon expression a sense of order and purpose. Name something and it’s important — in theory. Walker has fun with this silly but sensible nomenclature. He makes his points with his own doodles — some brisk and spontaneous — and many examples from mainstream and underground cartooning. In a full-page collage of sound effects, Robert Crumb’s work is present.

Some American readers got their first glimpses of European comic art in this book; Walker IDs some artists and character names, in a continuation of this droll anthropology. The visual essay “A History of Visual Humor in The Comics,” one of the book’s many appendices, is well-wrought and could be used as a learning tool for those new to comic art.

The Lexicon reached those immune to Bailey’s wizened charms — among them Chris Ware, whose introduction recounts his relationship with the book during his college days. It’s a work that any cartoonist will appreciate, and a worthy companion to Scott McCloud’s books in this vein. If newspapers had valued their comic strips in later years and not regarded them as a necessary evil, Mort Walker might have shown this side of his wit to a larger audience.

To the end of his days, Walker tried to make something of value with Beetle Bailey. The forum for his work failed him, as with most other newspaper cartoonists. Those who fought for more space, like Bill Watterson and Berke Breathed, gave up over time; it wasn’t a battle worth fighting for them.

It’s rare that I see current newspaper comics. There’s no reason to regard most of them. They’re gutted, empty things, their outreach smaller every day. The audience and leverage they had a century ago seem like a dim fantasy now. Legacy strips like Beetle, continued beyond their creators’ existence and not allowed a dignified death, mingle with newer features — most patterned on what has come before, rather than what might or could be. The destruction of newspaper comics is complete; it’s one of many reasons print media is in decline. Nothing lasts forever, and nothing is sadder than an entity that outstays its necessity and relevance.

The post Mort Walker, <i>Beetle Bailey,</i> and the decline and fall of newspaper comics appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment