On sale today and possibly not already sold out by the time you read this, Silent Pictures is an 800-piece boxed set of two 8.5" x 12" hardcover albums debuting the final completed color stories by Kevin O'Neill - among the most beloved of UK cartoonists from the late 1970s onward, who died in 2022. The publisher is longtime UK underground press Knockabout, not working in concert with the US publisher Top Shelf, as they often have in recent years; rather, this one can only be ordered directly from Knockabout or the London-based retailer Gosh! Comics. I am reading it off a PDF the publisher sent to me, and you should not take anything to follow as a comment on the reproduction quality or other physical properties of the package itself; the most recent book from Knockabout that I physically possess is 2024's The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic, to which O'Neill was a posthumous contributor, and that looked very nice, for what it's worth.

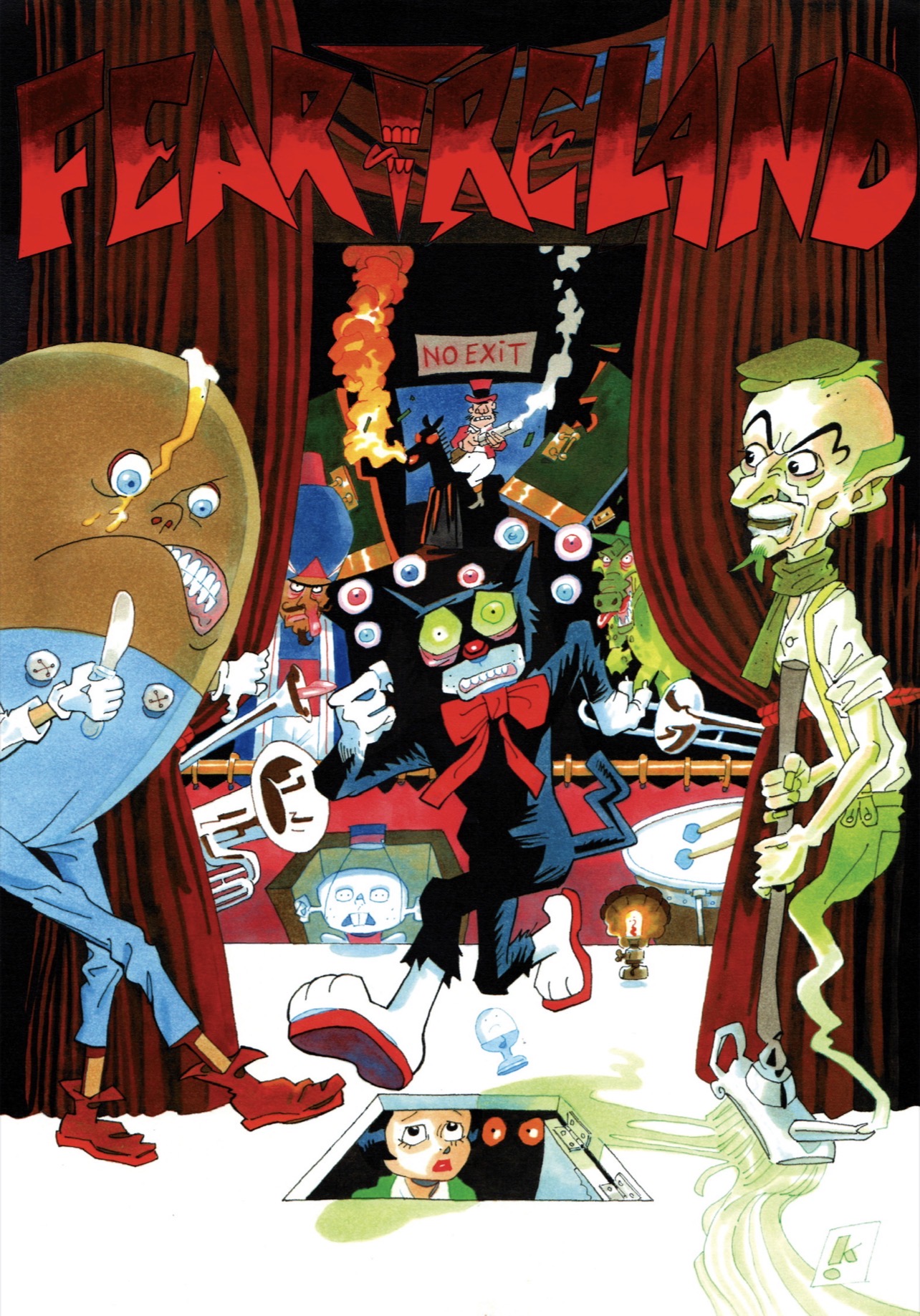

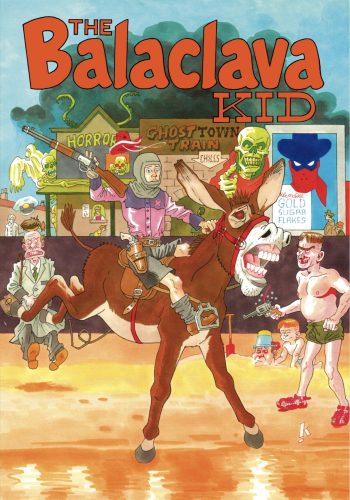

As is often the case with posthumous editions of an artist's unseen work, and as the limited nature of this release might suggest, it is serious admirers of O'Neill that will get the most out of these two books. Each contain 80 pages, most of which bear full- or double-page color illustrations, though some are divided into two or three panels. There is no narration or dialogue: "Silent" pictures. The first book is titled "Feartreland" (Theatre Land, put an accent on it, Theer-ter Land, Fear-ter Land) and concerns the antics of stage pantomime characters, among them an archetypical cartoon black cat and a spunky girl playing the trouser role of a male hero, who steal a magic eyeball from the odious Caliph of Pantopolis and barrel across fanciful panoramas of storybook creatures and folkloric villains; the second, "The Balaclava Kid," sees a bullied young boy from bombed out Monument Alley cold-cocked into a dreamtime escapade with figures evocative of the history of adventure comics and other entertainments circa the childhood of the artist: cowboys and knights, robots and funny animals. Each book includes a distinct introduction by the writer Alan Moore, who details the origins of the project and the editorial considerations behind its publication, in addition to offering his own interpretation of the stories from the perspective of a longtime friend and collaborator of the artist, informed by a great deal of biographical and cultural context.

Per Moore, these were pandemic projects for O'Neill, who was undergoing palliative care for the cancer that would take his life. Of particular interest, Moore notes that O'Neill considered these works "ready-to-go" shortly before his death, although the pages do not always seem 'finished' by the dictates of commercially published comics. "Feartreland" in particular often looks like words are supposed to be on the page; O'Neill completed a set of script notes, which were "difficult to make sense of," often consisting of scene descriptions related through "semi-comprehensible puns and word-play." There are no credits anywhere in the files I was sent, though Moore identifies Knockabout co-founder Tony Bennett, Gosh! founder Josh Palmano and O'Neill's wife Christina as involved in the assembly of the material — there were, at least, page numbers on hand to dictate the order of the images — and the decision was eventually made not to apply any text to the pages, as a reasonable argument could be made that O'Neill did not intend the pages to be shown in any form other than as they were found.

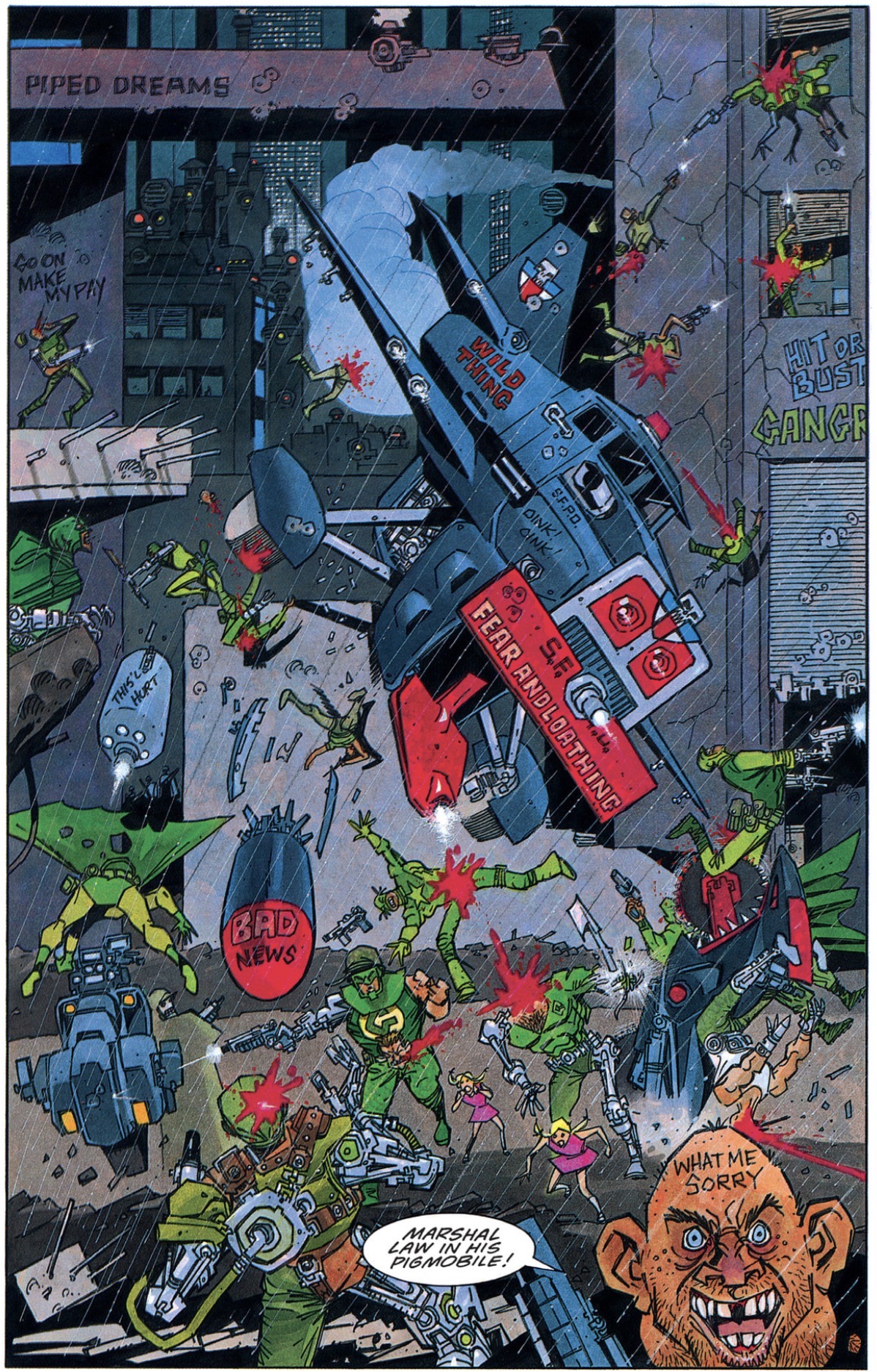

Of course, I am exactly the type of fervent Kevin O'Neill admirer I alluded to earlier, and I see much that is interesting in the book we have. It's a delight just to see him working in his own colors again, as much of his comics work in recent decades was either in b&w or colored by others - primarily Ben Dimagmaliw on The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. I like Dimagmaliw's colors as well, but I'm of the age where I became really fascinated with O'Neill through Marshal Law, his long-running travesty on superheroes with writer Pat Mills, which O'Neill generally colored himself with marker pens. So much of the atmosphere of that series — cold, hazy backgrounds of blue and grey, wet-looking rippling spandex and oily leather clinging to smooth skin — were products of O'Neill's painterly color sense. "Feartreland" is often gumball-colored, sometimes mossy and oaken, the tanned skin of a plucked rooster parading in slippers and knee socks shining as if rubbed with oil, as does the flesh of all un-furry characters here. There has always been a sensuality to the pillowy flesh of O'Neill's characters; it was most pronounced in his chaotic, near-abstract robot comics of the 1980s through Nemesis the Warlock, where pudding dollops of skin were forever surrounded by a million jagged metal edges, but this kind of eros, often disconcertingly independent of what is depicted, never left him even as age pared him down - his own color offers a crucial added component.

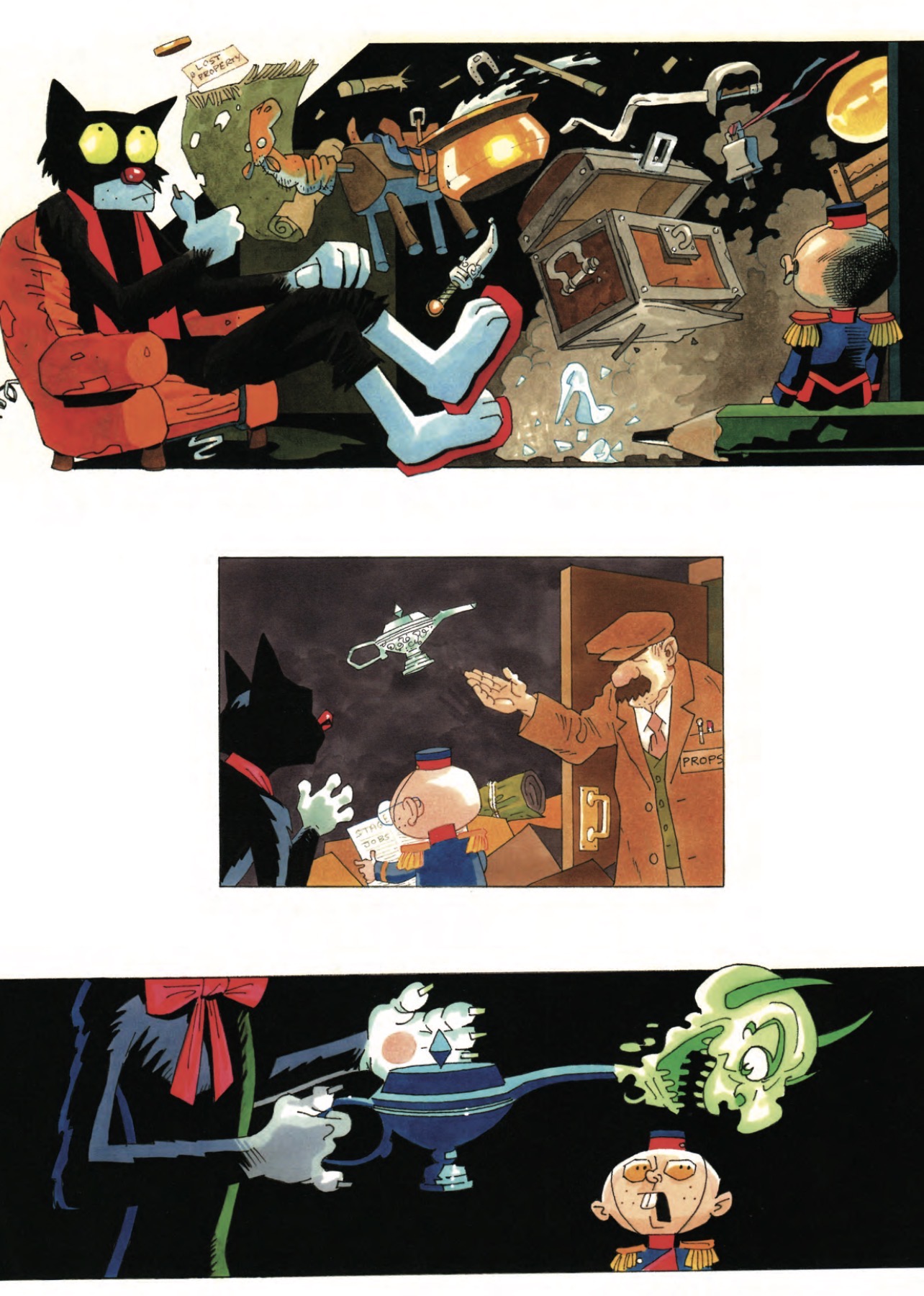

O'Neill's is a teeming art. Everybody (and Alan Moore here) correctly cites the English children's comics masters as his ancestors, Leo Baxendale and Ken Reid of the Beano, but this American has never not spotted the chicken fat of Will Elder in the great accumulation of tiny gags on his pages: Marshal Law might be the most overtly MAD of his major works, with League then directing the tendency so that nearly every gag is a specific drawing of some figure from the history of fiction. Sat at the end of the timeline, "Feartreland" is an overflow of archetypes, "a delirious cascade of childhood visions" per Moore, that has removed specificity from the image so that herds of men in music hall horse costumes, a genie emerging from a puff of humidifying absinthe, model toy movie gorillas and ogres, and a myriad of baying assassins with turbans and scimitars seem to issue from a cultural default, romping without comment. Many of the images feel self-contained as if they might summarize an issue of comics as cover art, but now it is all summary, driven forward only by the intuition that naughty characters must get into trouble with haughty authority figures and evade their pursuers until circumstance reveals them as heroes.

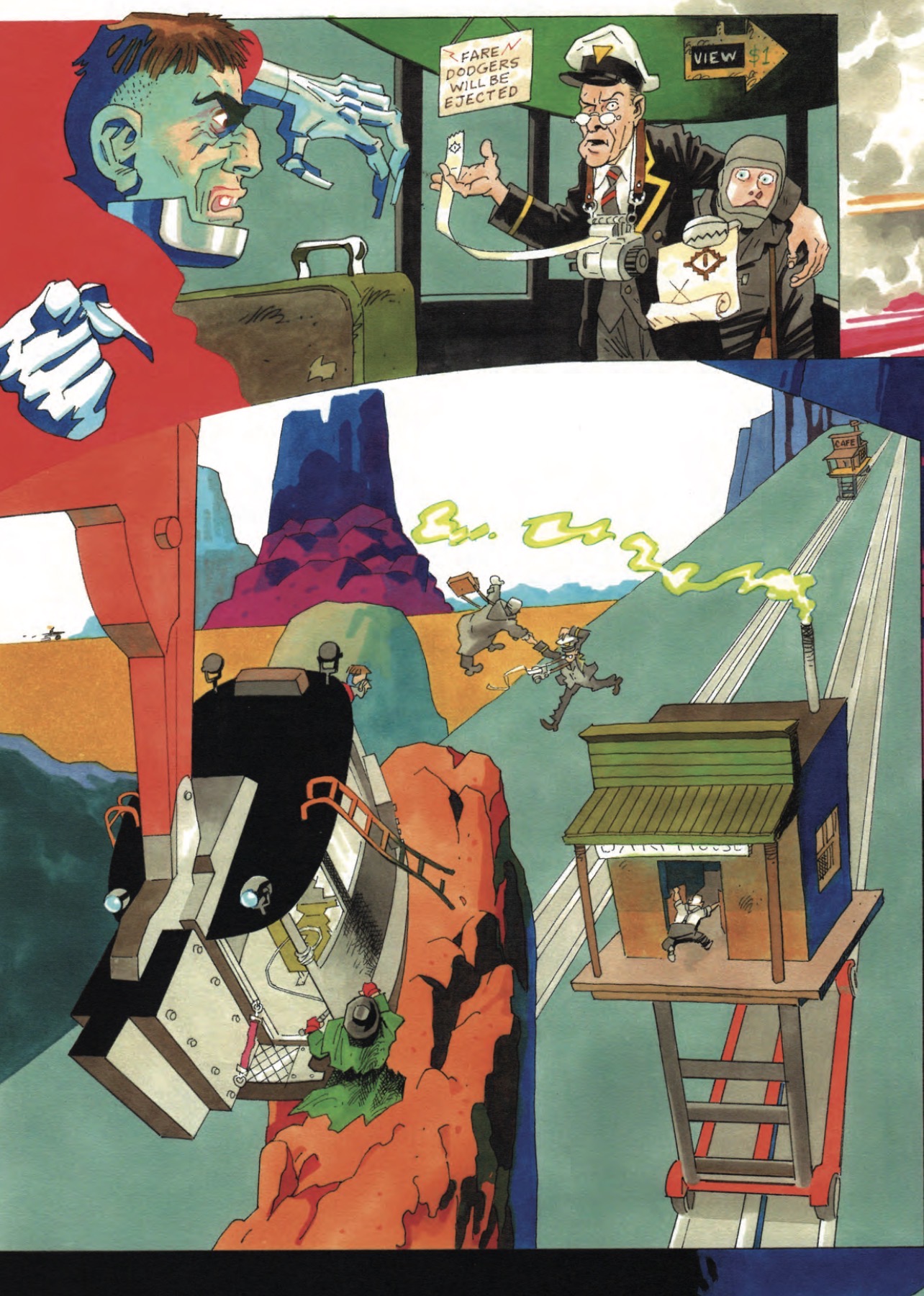

"The Balaclava Kid" was apparently finished last and is more sophisticated in its visual approach, in that O'Neill both frames its not-dissimilar chase narrative as a dream and integrates panels into the whole image by segueing from one to another along visual properties, so that the borders of panels curve like the contours of the vehicles characters are entering, or a rocky hill which characters are climbing in a top panel forms a sort of thought bubble over the head of an observing character in the panel underneath. On other pages, the images have no background or just a solid color, snatches of action surrounded on all sides by heavy white to seem like painted image boards for an animated film. The action is much 'harder,' dotted with explosions and bloody mayhem, presided over by a Denny Colt / Lone Ranger heroic outlaw figure with a fine, Tothian costume design.

Interestingly, this book feels as American as "Feartreland" feels British, given its cowboy movie / Chuck Jones desert setting and superheroic clashes. But to be American in this sense is to be as British as can be. In an interview with Douglas Wolk from 16 years ago, O'Neill characterized the postwar childhood experience of his generation of cartoonists as "a strange patchwork of British and American material," a "treasure hunt" of seeking DC, Marvel, Fawcett comics, vintage MAD, as they sailed over piecemeal from the States, like snatches of a fantasy. Silent Pictures, then, can be read as both cultural situations facing one another - two formative images of the past, one as-lived and one as-dreamed, recalled from the other end of life. The pleasures here are very particular, but powerful for those with the taste for it.

As a final note, I would ask you to pay especially close attention to the final pages of "The Balaclava Kid," which are 'unfinished' in a way the others are not. As the unconscious reverie of the boy hero fades, characters and background objects begin to go uncolored. Even as line art, they begin to trail off into pools of blank white. But this continues after the boy has woken up. In one image he stares directly at us, the color of his bloodied face surrounded by uncolored clothing, the same cold white as the winter snow in the background. A line art bicycle lies buried, half-drawn, in a snowdrift of the blank page. Nobody knows if O'Neill completed these pages in exact sequence, but I will imagine he was deliberate, or his instincts so true, that this story should trail off into a last unfinished sentence as it shuts its eyes.

The post Silent Pictures appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment