I don’t have children, so I’ve never had the experience of teaching them and reinforcing lessons. But I have had experience with relatives with dementia who have lost their memories, who are unable to make new ones, who are unable to recover what’s been lost, and in trying to guide someone untethered from their memories. It is, to say to the least, disorienting.

This all came to mind reading Roses in December (The Kent State University Press, 2015). The book by Tom Batiuk and Chuck Ayers collects two storylines from Crankshaft, a comic strip that the two worked on for 30 years together, until Ayers retired in 2017 and Dan Davis replaced him as the artist. I grew up with Batiuk’s Funky Winkerbean, which he wrote and drew until the strip was retired in 2022, but in the pre-internet days of my childhood I never knew there was a strip about a curmudgeonly ex-baseball player turned school bus driver named Ed Crankshaft.

People have called me a curmudgeon over the course of my life, and I liked the idea of a comic that was centered around a figure who wasn’t warm and fuzzy. But reading Roses in December, I found myself deeply moved in ways for which I was not prepared. And while it’s easy to say that the reason for that is because it reminded me of real life events, I believe that it’s more than that. The reason why captures some of what a comic strip is capable of doing.

1.

The storylines collected in Roses in December played out over many years in the Crankshaft strip. One concerns Crankshaft’s best friend, Ralph, whose wife Helen has Alzheimer’s. The other concerns one of the two sisters who live next door to Crankshaft.

As the book opens, Helen has been living in a home, and Crankshaft takes Ralph to visit her.

Over the course of the book we see Ralph spend time with Helen, though she rarely remembers anything about him or their life together. We do, however, through flashbacks, learn about how they met, when Ralph was a musician in his youth. Ralph sneaks her out of the home at one point and takes her to New York City, where they met, where they had honeymooned, and we see echoes of their youth matching the present day trip. Even if Helen doesn’t remember, readers are able to see the depth of their relationship and their history, which occupies half the panel space of each strip. The past is lost to Helen, but we’re able to see what is missing.

Before I had gone through certain experiences with my own family, I’m not sure I would have registered the weight of those strips. Read one at a time in the daily paper, it’s easy to read the then-and-now story as nostalgic or sweet. Saccharine, even. But read in one sitting, there’s a weight and a darkness there, which makes it far more than simply a cute story about an old couple re-creating their honeymoon. Ralph is trying to re-create their honeymoon, but he knows that Helen cannot remember it.

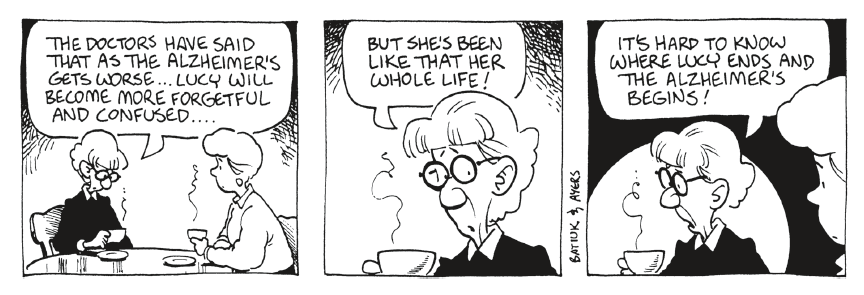

The other story in the book involves Crankshaft’s aforementioned neighbors, Lucy and Lillian McKenzie, as Lucy is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. After a series of incidents which range from the dangerous to the humorous, Lucy moves into a home, and later dies.

There’s a lot of truth in the strip just above; so much so that people with no experience may not understand. It’s why illnesses like dementia often don't get diagnosed immediately. After all, old people forget things and get lost and mix things up and can’t remember names and don’t know where they are. We have a term for it: a “senior moment.” Whether those moments are comic or tragic often depends on a medical diagnosis.

This highlights one key difference between the two storylines, united by an illness but otherwise very different. Ralph is the one who quotes James M. Barrie, the source of the book’s title: God gave us memory so that we might have roses in December. It’s a sentiment I find rather treacly. It’s a sentiment that Lillian would never express as she deals with her sister’s illness, at an older age than Ralph has to deal with it. Ralph has made his peace with Helen's illness on some level, and has come to accept what it means, but Lillian doesn’t have that opportunity. By positioning two very different scenarios together, Roses in December makes clear what Alzheimer’s is and what it means, and what it takes away, even as it demonstrates that there is no universal story.

2.

Time moves differently in comic strips than it does in real life. The ancient Greeks had two different notions of time: chronos and kairos. Chronos is the chronological time that we’re all familiar with in our daily lives, while kairos is a more complicated concept. To offer a brief and admittedly oversimplified explanation, chronos is time measured and counted, while kairos is time lived and experienced. Chronos is minutes and seconds, while kairos is numinous.

(And while it does feel pretentious to evoke here an ancient culture’s conception of time, I first learned the terms because Madeleine L’Engle used them to distinguish between her Austin Family Chronicles and Murry-O’Keefe Family Chronicles. You may have read those books too, at an age when you were reading the funnies page with great seriousness.)

The idea of two different notions of time is common. The Catholic Church differentiates holidays from “ordinary time” - a phrase I’ve always enjoyed. Or think of the way that schoolchildren know that time moves at different speeds depending on whether it’s summer vacation or classroom instruction. Kairos, I think, is well-suited to understanding how comics work.

In Peanuts, for example, Linus and Sally and Rerun grow up to some extent over the course of the strip, while other characters don’t seem to age at all - or, at least, not so noticeably. Arguably, such stylistic changes to the strip—the way that Schulz went from drawing characters like this to drawing them like that—can be seen as illustrating the passage of time.

But the Peanuts characters always remain children, so maybe what changes is what being “young” means. The way siblings and neighbors are no longer babies, and old enough to be included, to become a part of the group. And this can happen before the older ones have “aged out” of being a kid. They’ve aged, but in a sense, they haven’t really gotten older.

Similarly, I spent my entire life thinking of my grandparents as “old.” When I was born, my grandparents were in their 50s and 60s. When they died in their 80s and 90s, they were also “old.” My parents today are older than my grandparents were when I was born, and I’m not going to say that they are not old, but I don’t think of them as old in the same way.

The same way that my friends and I today are not old in the way our parents were at this age.

The same way that their children think that we are old, but are too well-behaved to say it. Out loud. In front of us. Usually.

3.

As I mentioned at the start, I am not a disinterested party to these issues. My grandmother had dementia. Not Alzheimer’s, though I will not bore anyone with the distinctions, which mean little to most. Including myself. What it meant was that for years before her death, my grandmother didn’t know who I was. Or she thought I was my father. Or she thought I was my uncle. Or she thought I looked familiar. She couldn’t identify her late husband, her parents, her siblings, or even herself in photographs. Eventually we understood that when she recognized us, she would address us by name. Once we understood that, we saw how rarely she addressed anyone by name, and we understood that this had been going on for a while.

The final years of her life were spent in a home, where her needs could be addressed. For a period of weeks before that, my parents and I cared for her 24/7. But even before that–before I realized that she didn’t know who I was and that this wasn’t an isolated incident, that she wouldn’t be forthright about what she could remember, or about what she was physically capable of doing–I remember watching her age. I don’t mean bearing witness to the at-a-glance evidence of aging, but aging as in losing memory, losing mobility. The very, very slow ways that a body and a mind can deteriorate in every way possible.

That process can be painful and excruciatingly long. It continues long after a person can remember, or speak coherently. Long after they’re capable of taking care of themselves. Long after you are able to do anything but witness it and make them comfortable and be kind to them, which seems to do little. But a child’s brain develops differently if they’re held and cared for, and we live in hope that at the end of life, doing so can still make some difference.

Roses in December reminded me of what a diagnosis means, and how that changes the way we read things like forgetfulness or other antics - it rang very true to me. A switch is flipped that affects everything. We live with people for so long that we don’t always notice their behavior changing. And then, suddenly, it’s impossible to ignore.

I wonder how I would have reacted to the book before all that. If I had read it serialized in the newspaper over years and gotten to know the two old ladies who live next door to the main character with their own quirks and habits, which were not unfamiliar from the older people I had come to know at church and in the neighborhood. What it would have meant for their behaviors to take on a very different meaning with a single medical diagnosis? One strip, one episode to change everything. Would I have found it true to life? Or would I have found it awkward, the equivalent of a Very Special Episode? I don’t think that having had this experience makes me a better judge of the strip's quality. If only people have who experienced something react positively to a work of art that depicts the thing, that often means the artist has failed.

I wonder how I would have reacted, because the same aspects that make it seem so awkward–that a character has been hijacked by the author and given an illness, which changes everything and nothing all at once–is precisely what makes it so realistic.

4.

Batiuk’s other major strip, Funky Winkerbean, was famous for the way it jumped ahead in time in 1992 and 2007, aging the characters and introducing a new status quo and different relationships. Crankshaft is simpler in terms of time. The main character has always been old–as grandparents are–and yet time passes, things change. People die and get older and move away. In some ways it’s like a book series, how Poirot and Spenser and Nero Wolfe change, but never really age.

This isn’t necessarily unrealistic. We often don’t think of ourselves as getting older the way others do. And we all know people whose lives have stood still, for good or ill, or who have felt stuck. People’s lives and careers move at their own personal velocities. There are people who will always be old, people we struggle to see differently even though they’ve changed. Others will never see us as we are - just how we used to be. That is why most of us go a little mad talking with our parents, who, no matter how much they try, seem incapable of treating us as adults all of the time.

Considering Batiuk has been a fixture in American newspapers for half a century, has created three comic strips and been a Pulitzer Prize finalist, there is surprisingly little written about him critically. Beyond, of course, people complaining on the internet and in letters to the editor that his work is depressing and doesn’t belong on the “comics” page.

Some of that is simply because, over the course of his career, Batiuk exchanged one set of influences for another: he began by making a strip that was comic in nature, and then switched to making a strip that was more of a serialized melodrama, albeit under the same title. Batiuk was 25 when Funky Winkerbean debuted, and it’s not surprising that he wouldn't have wanted to write and draw the same type of thing for 50 years - but from the beginning, Funky was never just a gag-a-day strip about high school hijinks.

I have probably read thousands of comic strips written and/or drawn by Batiuk by this point in my life, and one of the things that has always stood out is the way he balances this playful, often goofy sense of humor, with a darker and more complicated understanding of the world than is immediately evident. He often struggles to place these two elements side by side; on the modern comics page, they tend not to even exist in the same strip.

Still, from the beginning of his career, Batiuk has been interested in finding a way to portray adolescence in a more nuanced manner than often shown in contemporaneously daily strips. Funky Winkerbean could be frantic and crazy, and used the medium to lean into that, but it was also a strip that had anxiety and pathos built into it: about gym class and getting stuffed into lockers; about planning the day around bullies and the capriciousness of teachers; that so much of high school seems unimportant compared to spending time with one’s friends and dating; about how daily life could change on a dime and suddenly become very serious. The adults in the early years of the strip were often presented as comic relief, delusional at times and constantly defeated in different ways. But for all the goofy humor, the kids didn’t fare much better.

I don’t think that Batiuk’s sense of the world has changed all that much. Or, rather, I think he has continued to see the world in similar terms, but how we deal with it changes as we get older. How we goof off changes. What "failure" means changes. We come to understand our lives backwards and forwards, where once there was only the future ahead of us.

Gasoline Alley is one of the greatest comic strips ever, and formally magnificent for the ways that Frank King managed to depict the passage of a single day, aging his characters one episode at a time. More recently, Lynn Johnston’s For Better or For Worse was masterful in how she handled the gradual march of time. But she was the exception. For the most part, little changes on the comics page anymore.

I don’t know whether Batiuk deliberately considered, after he initially jumped the Funky cast ahead to life after high school, to let them age in real time, or if it just happened. But as someone roughly half Batiuk’s age, high school being about Star Trek and the Battle of the Bands and grades, and then getting older, and life becoming slower and less zany and more serious - it feels realistic. Batiuk likes a good joke (a bad pun, a good visual gag) - that hasn’t changed. To be in the school band and watch the band leader’s mad dreams get dashed on the rocks year after year: that’s funny. But as the kids grow old and have to deal with their dreams being dashed on the rocks: that’s less funny.

When they were in high school, Les was bullied by Bull. Bull bullied just about everyone. It wasn’t played for laughs. The point wasn’t to laugh at what happened to Les, but Funky Winkerbean was centered around Les and his classmates, and while the experience wasn’t exactly traumatic, bullying was something that shaped what Les did at school, where he went and when. After the strip jumped forward, one of the storylines concerned why Bull was the way he was. Specifically, that he had been abused by his father, and so he fought and beat up other kids.

Is the strip depressing for explaining this? Yes, but it’s also the whole story. Hannah Gadsby had a very elegant and thoughtful explanation of the difference between a joke and a story in her comedy special Nanette, and what it means to make a story into a joke. To explain would take an essay in and of itself, but the idea is that a joke is only a partial truth of an experience in a moment in time. There are ways to tell jokes, but also to accept that there are some things that jokes can’t do. This is something that Tom Batiuk has understood for a long time.

The full story is always dark and hard and brutal and depressing. (See: history.) I won’t claim otherwise. But the idea that it is only that is something that I will push against. Both in life and in the comics.

Consider the death of the Funky Winkerbean character Lisa in 2007, as she is ushered offstage by a masked figure in a tuxedo. Or how in Roses in December, after a long brutal illness, Lucy’s death is not so brutal. Batiuk has had cancer, and I’m sure he has been with people who have died, and he takes such great care to depict illness and deterioration, to depict the toll illness takes on caregivers and family members. He wants readers to feel it. In life, so often one is bludgeoned to the point of exhaustion. He does not sugarcoat anything, but also he doesn't make death harder than it already is.

Lucy’s death and final moments are left unseen. Instead, her sister Lillian receives a haunting. Not a painless one—hauntings never are—but one that ends with a moment of grace and release. At heart, Batiuk has a comedic and light sensibility. Of life and of death.

5.

John Gardner wrote about the “vivid and continuous dream” to which fiction aspires; graphic novels certainly aspire to that, but comic strips do not. The daily rhythm and structure of a daily strip, whether part of a larger narrative or simply a one-off gag, is designed for reading in isolation. It is intended to come after one strip and before another, although it may not be dependent on them. In reading collections of comic strips, this jerky start-stop rhythm becomes apparent. Some creators are able to finesse the story in ways that are elegant, while others manage to capture that feeling of time passing between strips.

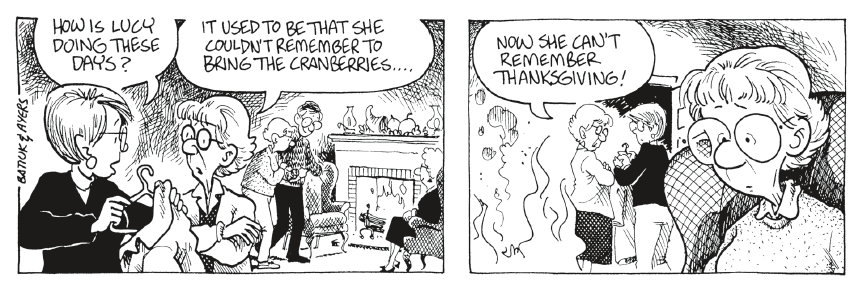

I think what makes the stories in Roses in December work so well is the fact that they unfold over years, in bits and pieces, in between other episodes. The book does not collect every individual Crankshaft strip from all of these years, but it bundles weeks of strips together where the illness is touched on in some of those strips, if maybe not all of them. In doing so, the collected book manages to capture some of that rhythm of daily life - not simply telling a story in bite-sized pieces, but embodying the way that we are reminded of something and then move on. These strips likely still read better over the course of years on a daily basis. In a book, it can be jarring to have a strip about, say, Crankshaft dusting with a leaf blower, or his grandson and his band. Then there will be strips about Thanksgiving, but also about forgetfulness - how every year Lucy forgets the cranberry sauce, a running gag that is now something much darker.

That’s the way that dementia often feels. Sometimes it’s front and center, and other times it’s not, because sometimes one can forget and get on with other things. A comic strip functions as a daily encounter with people; this is why so many of the strips with large ensemble casts are able to function, because they are trying to mimic those brief interactions of our lives. The best strips understand that events are happening to characters off-panel. In Crankshaft, we go for stretches without seeing Lillian and Lucy - and even when they pop in, it’s not necessarily to talk about Alzheimer’s. However, when they do appear, Batiuk and Ayers take great care not to simply show Lucy retreating and becoming less talkative, less engaged, but also how Lillian is handling all this. To show the strain and the pain and the exhaustion of taking care of someone.

There's a saying, sometimes attributed to the writer Clifford Odets: “Any idiot can face a crisis; it’s this day-to-day living that wears you out.” We are able to rally in moments of trial, but as days turn to weeks and weeks to months, as a person’s condition deteriorates, it often is no longer possible to care for them. In the strip, Lucy understands what’s happening, and that her sister can no longer take care of her. For some of us, this is one of the least realistic moments of the saga. But emotionally it works, because Lucy is saying goodbye to her sister. Even if she may not be able to remember doing so the next day.

As I mentioned before, Lucy's ghost appears to Lillian at the end of the story. With Ralph and Helen, the past was clearly marked; here it very intentionally is not. Lillian is forced to confront not just Lucy, but her own actions. She follows her sister to an abandoned park on the edge of town, and Lucy tells her to rid herself of a particular letter she has been hiding - one that has been the source of much guilt for Lillian over the decades. An act of grace, to leave her burden behind, and to let her sister go.

To accept the lightness of being means accepting the absence of any ultimate meaning to life. Instead, it means seeing life as a series of moments. (A series of comic strip panels?) Teaching a young girl to knit. Lost love. Getting stuck in the snow during a storm. Being unable to remember one’s address and understand the signs. Of the neighbor calling the cops on your choir practice. Building a snowman in an effort to recapture that joy of childhood. Winning a dance contest. Falling asleep in the attic, just as one did as a child.

Batiuk’s world is not bleak. In his comics, people are more than their final moments. They are more than their illnesses. They are more than their lost memories. They are more than their best days and more than their worst days. They are individuals with long and complicated and messy lives. Part of a vast community that continues after they’re gone.

An unnamed construction worker discovers the letter left by Lillian and takes a moment before placing it back where he found it, and then he returns to demolishing the amusement park. For whatever comes next. Something always comes next. The dance goes on.

The post The Dying of the Light: My Grandmother, Dementia, Time in the Comic Strip, and <em>Roses in December</em> by Tom Batiuk and Chuck Ayers appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment