Many an observer has stated that we are experiencing something of a Golden Age in the world of independent and self-published comics, and who am I to argue with facts? It wasn’t so terribly long ago that it felt like almost nothing good was coming out, and now we’re facing a situation that’s 180 degrees removed from that: there are almost too many unique, well-done, highly individualistic comics to keep up with, made by people who want to expand the boundaries of the medium, use it to express their truths and tell their stories, and bring others along for the ride.

Indeed, comics is now a more inclusive art form than it’s ever been in the past, and as work from creators who come from marginalized and/or oppressed populations finally finds the recognition it has long struggled for and unquestionably deserves, the divisive, confrontational and often upsetting visions committed to paper by the likes of Rory Hayes, S. Clay Wilson, Greg Irons, Jim Osborne and their like is seen by a good number of folks as being hopelessly passé, a relic of a regrettable bygone age drenched in (and celebratory of) almost any social ill you care to mention, misogyny being chief among them.

And yet, the knee-jerk contrarian in me asks: isn't there something inherently unhealthy about starving the darkness in favor of feeding the light? Good comics are easy enough to find, but confrontational and unsettling work is becoming something that you really have to hunt around for - and for an art form to reflect life’s totality, it first needs to encompass it. While authors such as Dennis Cooper, Audrey Szasz, B.R. Yeager, Charlene Elsby and many others are riding an ascendant wave of transgression in the literary world (thanks in no small part to specialist publishing houses like Philip Best’s Amphetamine Sulphate and Ben DeVos’ Apocalypse Party), comics in general seem to be closing ranks around the idea that excess, decadence and even base id regurgitation are little more than reminders of an embarrassing past - best ignored or, barring that, piled on with scorn and derision. “We’re past all that now,” as more than one friend has told me.

I’m sorry, but - WHAT?

There’s no greater evidence that comics probably still has some growing up to do than the idea that they can’t and/or shouldn’t be whatever the people making them want them to be. The notion that we have “arrived” at a certain point and can’t “go backwards” is inherently offensive to anyone who thinks that comics—like ANY OTHER ART FORM—should be free to explore any subject matter whatsoever. “If it’s in you, it’s gotta come out,” as the old saying goes, and I’m far from the only reader with an active interest in seeing this medium used as a means by and through which to reconnoiter the abyss - be it personal, social, or global. In a world where the likes of Crumb and Johnny Ryan are held in increasing contempt, you’ve REALLY got to wonder what would happen if Mike Diana were busted today. My best guess is that some of his fiercest critics would come from within the comics community itself.

I state this not in order to dredge up another tired debate about so-called “cancel culture,” but to point out the obvious fact that comics won’t need the stifling forces of conservative conformity to censor them if we impose a de facto censorship regime ourselves - and that’s something I’d dearly like to see avoided at all costs. In order to ensure such a depressing eventuality never comes to pass, though, it’s vital to not only support, but to champion work that shocks the conscience, pays no heed to decorum, challenges one’s sensibilities, and even pisses off the (frequently self-appointed) good guys. Work that colors outside the lines, sure, but also work that rips those lines to shreds or simply refuses to acknowledge their existence in the first place. Work of that sort you’ll find in the pages of publisher/editor (and damn fine cartoonist) Harry Nordlinger’s increasingly transgressive horror anthology series Vacuum Decay, which serves as a necessary counterpoint to all the respectability comics has accrued to itself in recent years.

Eschewing playing nice in favor of playing for keeps, Nordlinger—who has “ported over” his previous short-form solo project, "Softer Than Sunshine", into this series’ pleasingly cream-colored pages—has revealed a clear-cut but in no way inflexible developing editorial sensibility in his three years at the helm of this series, one that takes “abandon hope all ye who enter here” as its starting point rather than its ending, and proceeds to “go there” in ways not seen in a horror comics anthology since the heyday of Stephen Bissette’s Taboo. Whereas Bissette’s inclinations—as well as his numerous A-list industry contacts and friendships—resulted in a series with a more literary bent, however, Nordlinger has made no bones about his fondness for the purely visceral from the outset. Depravity for its own sake is a largely undervalued field of artistic endeavor, but it’s not shied away from in Vacuum Decay - indeed, “shock schlock” is the stock in trade of regular contributors such as Andrew Pilkington, Nik Ruby, and the previously-mentioned Mike Diana.

You largely know what you’re in for with these cartoonists’ strips: stomach-churning scenarios strung together over skeletal plots in service of amoral (to put it kindly) ends, but this in no way negates the import of such work. After all, in a world trending disturbingly toward atomization, isolation and self-absorption, radical measures are required to stand above the digitized din that serves as our constant-but-decidedly-pale approximation of “interaction.” Inviting someone to pay attention to the art you’ve created is all well and good, but art that compels or demands one’s notice, even if the most common reactions to it are outrage and condemnation, is a powerful weapon in the arsenal of any self-respecting aesthetic terrorist. When Pilkington depicts a baby’s innards being ripped out along with its pacifier, or Diana shows an abusive parent throwing his living son into a deep fat fryer and then eating him, no one’s going to argue that these aren’t crass, immature, and frankly cheaply exploitative works - the questions that largely go unasked, however, are where any medium would be without artists willing to indulge in absolute extremes, and why repugnant visions retain their ability offend most audience sensibilities even after decades of deliberately disgusting “slasher” films and the like. Like the kid in the back of the classroom drawing blood-drenched doodles of the teacher getting his or her head chopped off before their entrails are served up in the lunch room, “dude, you’re fucked up” is precisely the reaction these cartoonists seek to engender, and it’s altogether more honest—if less pleasant—to engage with their work and examine the impetus behind it unflinchingly than it is to brush it off and pretend it doesn’t exist.

Even still, Nordlinger’s predisposition for commissioning existentially bleak and shockingly violent strips has never functioned as a de facto “boxing in” device, nor has it resulted in the contents of his book weighing too terribly heavily toward any one particular “kind” of storytelling. Karmichael Jones, for instance—the only cartoonist save for Nordlinger himself to have appeared in all six Vacuum Decay issues to date—utilizes art that verges on being unbearably detailed to delineate Grand Guignol stories that are equally horrifying for their absurdity as well as for their uncomfortable relatability: soul-dead suburban commercialized existence being the ultimate recipient of his adroitly-honed ire. Michael Falotico’s “body horror” indulgences offer a gutter-level vision of corporeal existence itself as the enemy that even the likes of Huysmans might approve of (if it were presented in a more romanticized style and context, mind you, which is hardly the case when we’re talking about, say, a deformed kid who can’t make friends because he can’t stop shitting). Corinne Halbert’s neo-decadent (and decidedly gorgeous) strips appropriate sci-fi, giallo and “nunspoitation” genre tropes in a manner that dispenses with all pretense and directly explores the connection between sex and death with unflinching honesty. David Enos weaponizes a narrow but creatively fertile range of emotions from longing to lust in service of cautionary tales that emphasize the chasm capitalism digs between our desires and their fulfillment. Happy endings aren’t just in short supply in this anthology, they’re nowhere to be found - but how the existentially bleak resolutions (or non-resolutions) we receive are arrived at, and what they represent, run the proverbial gamut.

Within what would appear at first to be a fairly tight editorial remit, any number of exceptional cartoonists are finding myriad ways to unleash the reprobate imaginings we all have to one degree or another - the key difference being, of course, that these individuals all have guts enough to own up to theirs, and don’t shy away from blatant (if sometimes silent) statements vis-à-vis their ramifications. The “lost” biological monstrosity in Karmichael Jones’ “Have You Seen Me?” (Vacuum Decay #2) is right there “hiding” in plain sight but no less anonymous for that fact; the Saw-style “torture porn” practitioners in Mavado Charon’s untitled stirp in issue #4 (arguably the most physically and conceptually repulsive story to appear in the series to date) find mutually depraved satisfaction more by accident than design, but are you just gonna have to do the whole thing over again? Nordlinger’s own shadow-side version of Homer Simpson in issue #5's installment of “Softer Than Sunshine” finally manages to permanently rid himself of the perpetual nuisance that is Bart, but has to start offing the other members of the family in order to keep them from asking too many questions about where the world’s most famous juvenile delinquent has disappeared to - you get the idea. One-way tickets to oblivion are more or less the only kind being offered here.

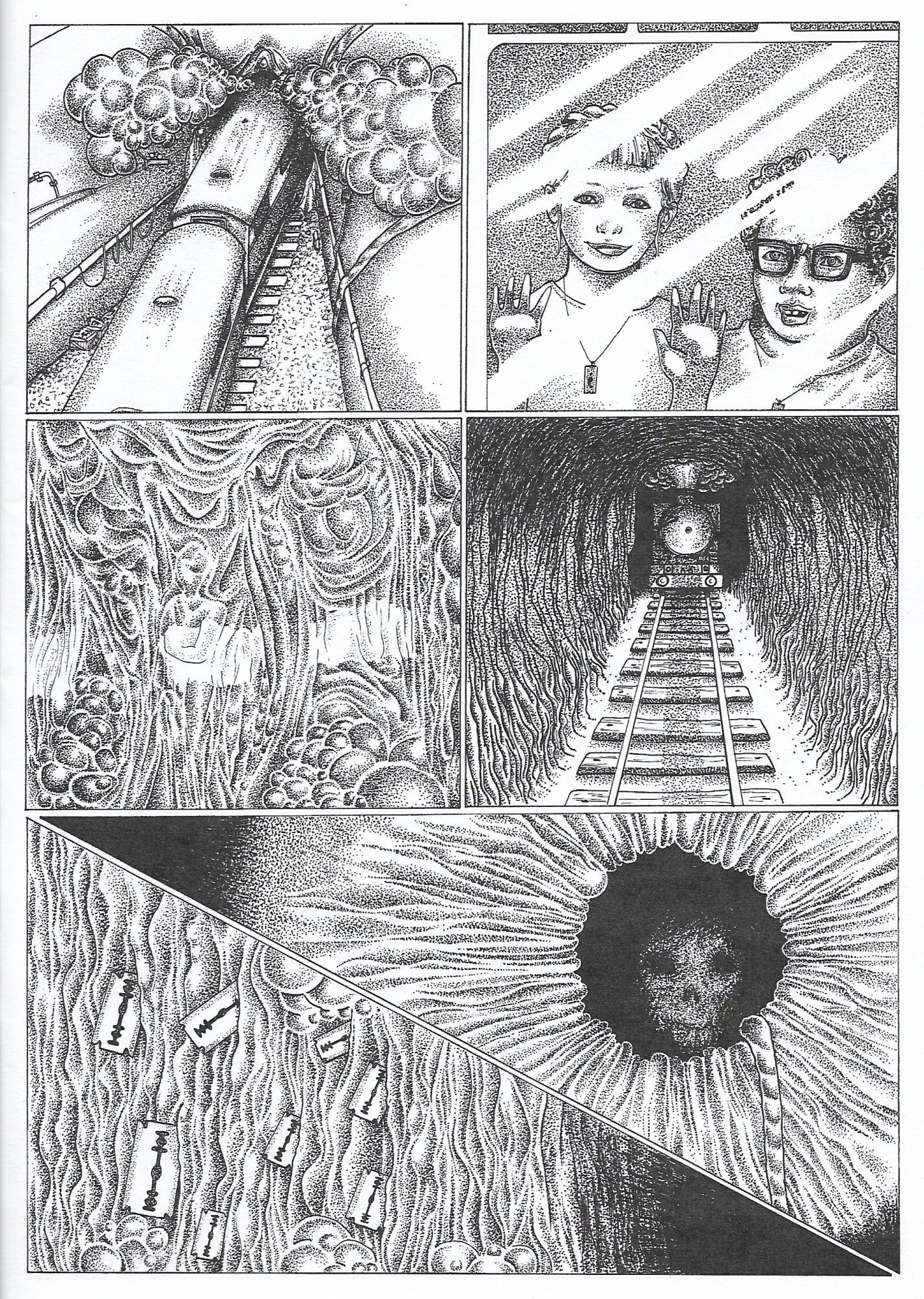

Perhaps most pleasingly (a term that I suppose, all things considered, I’m using advisedly), though, is that as this series has progressed, Nordlinger has also begun to present more work best described as being highly interpretive in nature, the best examples being a tantalizing and symbol-rich melding of the modern, the medieval, the mythological and the vaguely Lovecraftian from Chloé Burt in the recent issue #6, and an elliptical, transcendental, harrowing and obliquely confessional visual exegesis on the pains and pleasures of harm (whether induced by the self or by other parties) by the always-amazing J. Webster Sharp in issue #5 that is next-level stuff even by her lofty standards - and that will, fair warning, come roaring back to your mind whenever you hear someone use the term “running a train” again, so inedible is the imprint that it leaves. The essential character of what I suppose we could call (for lack of anything better or more handy) the “Vacuum Decay ethos” remains unchanged by the inclusion of material with loose-to-non-existent relationships with narrative, but the aesthetic methodologies by which its various highways, byways, and tributaries are being mapped is becoming broader, more multi-faceted, and more thrillingly dangerous in both ideation and execution. What began as an underground horror anthology still is very much that, but transgressive art is no respecter of limitation or boundary, and the contents of this series are becoming increasingly reflective of this sensibility - or, perhaps more accurately, of this obliteration of sensibility.

It's also proving to be a welcoming home for reasonably well-established cartoonist who have made names for themselves doing work damn near 180 degrees removed from what you’ll find here, and in that sense it’s become something of a “release valve” for the darker impulses of, say, a Jasper Jubenvill, a Pat Aulisio or a Joakim Drescher, all of whom have contributed strips to Vacuum Decay that fit in better when presented with like-minded company than they ever would or could in the pages of any of these artists’ own books. Even Ian Sundahl, whose comics are planted pretty firmly in the world of dive bars, shady drifters, and muscle cars rolling along dusty desert roads in the middle of the night as a matter of course, takes things a bit further with his contribution to this series’ fifth issue, which hinges on a bizarre physical deformity (I’ll say no more) that wouldn’t work nearly as well within the context of a Social Discipline story. As stated earlier, “it’s in you, it’s gotta come out,” and it’s rather impressive to see just how many noteworthy talents have chosen Nordlinger’s anthology as the place to let their freak flags fly.

Even still, for all the talent on display here, there’s no avoiding the simple truth that we’re talking about a project that will, by its very nature, be of interest to only a very small audience, and that will actively appeal to only a fraction of that. Those with delicate sensibilities are advised to stay the hell away, of course, but I’d caution even those with an interest in exploring depravity to think long and hard before going down this road. It’s both as “ultimate” and as “extreme” as “ultimate extremes” come, and it’s best to go into any given issue armed with the full knowledge that there could well be things seen within in that can’t be unseen. I’d never be so foolhardy as to suggest that Vacuum Decay is a comic that most people will find necessary - but its continued existence is absolutely necessary, both as a counter-balance (or, if one views things in more militant terms, a necessary corrective) to the affirmational narratives that dominate the independent/small press/self-publishing scene as it exists today, and as a dynamic and evolving wrecking ball aimed squarely at acceptability’s outer limits. That it exists to shock and offend is never up for debate - but the importance of shocking and offensive material is too often lost in this medium’s endless, tedious chase for an ephemeral “respectability” that quietly bludgeons the sharper edges of self-expression in exchange for acceptance by and among the patron class.

We’re all well aware that when you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes back - but for those who have been there and done that innumerable times already, Vacuum Decay ups the ante both quantitatively and, more importantly, qualitatively: the abyss is challenging you to a staring contest, daring you to blink first. And it’s probably going to win.

The post Transmissions from the Void: On <em>Vacuum Decay</em> and Harry Nordlinger’s Evolving Nihilistic Vision appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment