Among the new inductees to the Will Eisner Hall of Fame this past July, one surely stood out to those beautiful souls who know the names down the page: Diana Schutz. While an accomplished writer and translator, Schutz is known best as a longtime industry editor, with significant tenures at Comico and Dark Horse; she served as editor in chief for both, and spearheaded the much-admired Maverick line at the latter. She has worked directly on major releases by Frank Miller & Lynn Varley, Eddie Campbell, Matt Wagner, Harvey Pekar and countless others, but the true scope of her career encompasses almost every aspect of comics as art and industry, from retailing at the late 1970s dawn of the direct market to teaching in the 21st century blossom of comics studies. Now freelance, her work continues on projects like Blacksad, the wildly popular series by Spanish authors Juan Díaz Canales & Juanjo Guarnido, which Schutz translates in collaboration with Brandon Kander.

It's been 12 years since we last checked in with Schutz, and her energy remains undimmed. The following interview was conducted in writing in April and May of 2023, with subsequent edits and revisions through September.

-The Editors

PAUL NEAL: How did you discover comics? Can you recall the first ones that caught your eye and impressed you, or where they were from?

DIANA SCHUTZ: The thing is, I learned to read in 1960, when I was five, and comics were everywhere in those days! At the grocery store, corner mom-and-pop shops, on the spin racks at lunch- and soda-counters, at the newsstands on the street. Comics were just so much a fact of everyday life that it’s hard to pinpoint exactly when I became aware of them.

That said, two formative memories loom large. My late father was a dentist whose waiting room contained not only “grown-up” magazines, but also comic books! He worked in a dental office with other colleagues, including an orthodontist who brought in his children’s secondhand comics for the kid patients. Stacks of Mort Weisinger-edited DC superheroes! So, that’s certainly where I discovered Supergirl, my all-time favorite—especially as drawn by Jim Mooney, an artist whose name I wouldn’t even learn until decades later but whose Supergirl I could art-spot even as a child.

One more strong memory, also from the early ’60s: my cousin Kenny let me read his precious Marvels, and while I have vague recollections of the first issue of Fantastic Four, I was still too young to really “get” Marvel’s superheroes, whereas I became totally hooked on those cautionary Cold War tales of nuclear paranoia and alien invasion. Steve Ditko was the other artist whose work was immediately recognizable to me as a kid, maybe because it was so radically different from Mooney’s more straightforward style? Ditko’s deep shading around the eyes, the prominent, thick lips on his women, the spare, otherworldly design of his panels or splash pages—his work gave me the creeps, but I couldn’t get enough of it.

There’s a daft question I like to ask anyone who has worked on or enjoys superhero comics. If you could have one superpower, or the abilities of one character, what power or whose abilities would you choose?

Oh, that’s easy. Supergirl, for sure—the original 1958 creation. She was an adorable blonde, goodhearted teenager who could do anything her more famous cousin could do. Who wouldn’t want that?! Well, at age five, I mean.

How did you first come to work in the comics industry?

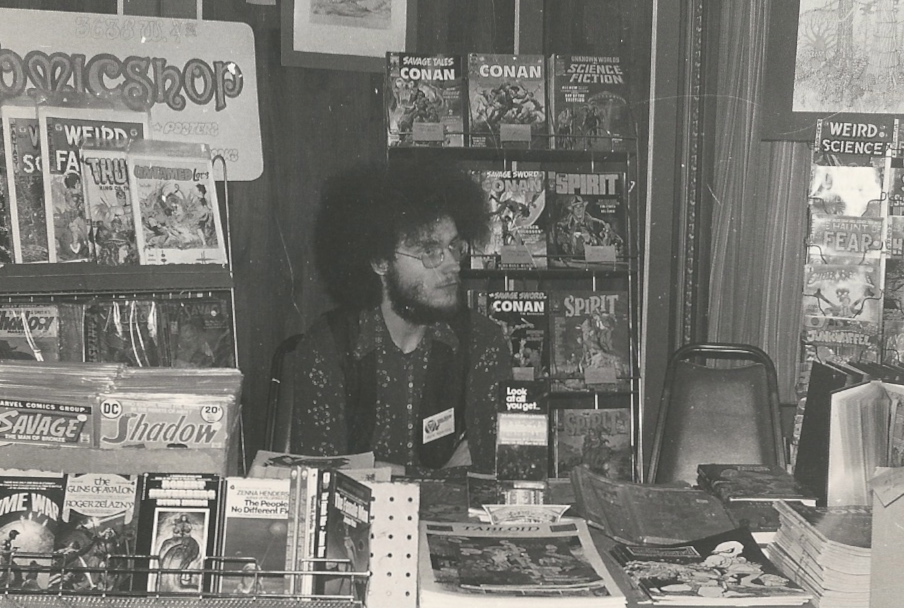

In 1978, I was two years into a PhD program in Philosophy at the University of British Columbia, but I was feeling out of my element. I’d been in school for 18 years straight at that point, and by then, I’d rekindled my previous passion for comics, and started collecting. The 1970s, of course, marked the growth of the direct market of comic book specialty shops in the US, and Canada was no exception. I’d discovered The Comicshop in Vancouver, near the UBC campus, not long after it opened in 1974—which was like discovering Oz—and when owners Ken Witcher and the late Ron Norton offered me a job, you bet I took it. It was Ron and Ken who gave me my first real education in comics, and it was at The Comicshop that I finally found my tribe. I worked comics retail for six years, moving in 1981 to Comics & Comix in Berkeley, California, where I also began writing reviews, doing interviews, and editing a xeroxed store newsletter that soon morphed into a 32-page bimonthly print magazine called The Telegraph Wire. All of which would lead, in 1985, to a job offer at Marvel Comics as Annie Nocenti’s assistant editor. A job that lasted four days!

Oh wow. What transpired in those four days?

I think it was a case of … be careful what you wish for? I had only ever worked for very small companies before, when, at age 29, I found myself with hordes of commuters, taking the train every morning to a midtown Manhattan corporation—Marvel Comics, that is. I was still a west coast hippie, a comics fangirl who was suddenly surrounded by high-powered New York professionals—and once again utterly out of my element. I’d been recommended for the job by some friends—Christopher Claremont, Frank Miller, and Annie’s outgoing assistant, Marvel historian Peter Sanderson—and working as the assistant editor on Uncanny X-Men in 1985 should have been my dream job … but it wasn’t.

Though people have apparently now forgotten, the 1980s were a profoundly political time for comics. After four decades of Draconian work-made-for-hire contracts as their only option, writers and artists were seeking rights of authorship for work they created. But in those days, there were just a handful of independent publishers offering copyright ownership and royalties. Even returning the physical artwork to the pencilers and inkers who had drawn it was still a relatively new practice! And we were all learning just how badly Marvel had exploited Jack Kirby. Archie Goodwin’s Epic imprint notwithstanding, overall policy at Marvel was not what I would call creator-friendly, another reason I didn’t feel at home there. Mind you, I learned a lot in four days, and Annie was a pretty simpatico boss, but on day five I was scheduled for what the editors called my “indoctrination lecture” with Marvel’s then-editor in chief, Jim Shooter. Indoctrination lecture! Apparently SOP for all incoming editorial staff. Honestly, I was terrified. I’d heard all the horror stories—Shooter was not especially well liked during his tenure as editor in chief—and I called in that morning … and quit. A decision I don’t regret, except for leaving Annie in the lurch. Having gone on to hire countless assistants myself, both at Comico and then for 25 years at Dark Horse, I find hiring—and personnel issues generally—to be a grueling part of the job. Worse, that’s time away from the joy of making books. I’ve hired plenty of assistants who didn’t work out for one reason or another, and finding the right person is difficult. So, I’m sorry that Annie had to look for a new assistant again after only four days, but a midtown Manhattan corporation was never going to be a good fit for someone like me who’s allergic to bureaucracy in the first place.

All that said, I took what I learned at Marvel, especially the making of comics production schedules—thanks to Virginia Romita, wife of the late John Sr. and Marvel’s then-production manager—and brought that skill with me a few months later to Comico, and then in 1990 to Dark Horse, where it was really needed!

What were your duties at Dark Horse?

I rode into Dark Horse exactly the same way I had ridden into Comico five years earlier: on the generous coattails of my then-husband Bob Schreck! In 1990, Dark Horse was a company of only 10 people, working out of one big room, spearheaded by publisher Mike Richardson and editor Randy Stradley. I was hired as a second editor, their first female editor. In fact, the only other woman on staff back then was the receptionist. But I was aghast to learn that they had no schedules at all! No individual book schedules. No master printing schedule for the line as a whole. And their printer was some crappy outfit in Florida that blew every deadline. No wonder Dark Horse hadn’t been able to get any books out on time. Really, in 1990, after only four years in business, Dark Horse was best known in the industry for publishing late books. Good ones, but late.

In fact, my first mandate at Dark Horse, per Mike Richardson, was to get Aliens vs. Predator published—in only four months! They’d been soliciting for that series for a year and a half but hadn’t been able to get it out. That’s because the penciler was off making more money as a storyboard artist. Well, the book needed a new penciler, obviously! And the company needed book schedules, a master printing and production schedule, and a new printer. So, that’s what I did for them. The trains started running on time. I was hired March 5, 1990, and Aliens vs. Predator #1 was published in June 1990. It sold half a million copies and made the company oodles of money. Ask me what I made.

No, don’t.

This is a tricky question to ask, but I can only ask it bluntly: at that stage in your career, did you ever experience any sexism, blatant or subtle? And if that was the case, have things improved?

Well, yeah! Of course I did!

And yes, things have improved, but they sure ain’t perfect yet.

The comics industry was a total Boys Club when I first began working in the field. But it was the late ’70s, and comics were no different than anywhere else. In grad school at UBC, one of my professors had flat-out said, If you don’t fuck me, I’ll make sure you never get your PhD. Well, I didn’t—and I didn’t. By the ’90s, when I went back to university for my M.A. in Communication Studies, things had changed. Or were changing.

And comics … well, the customers who really don’t want you ringing up their purchases, who look just off to the left of your eyes if forced to say two words to you, who assume you can’t possibly know—let alone care—that Bill Sienkiewicz is filling in for regular Uncanny X-Men artist Dave Cockrum on this month’s issue. The married supervisor whose “friendly” hugs always last just a bit too long. The colleague who leans in, expecting a kiss when you’re just shooting the shit with the rest of the editors over one drink after work. The stupid porn pinups that come down because you get hired—not because you’re asked or you particularly care. The resentment created by those more or less good intentions on the part of your boss.

Women of my generation were treated as women first—consciously or not. Our career roles were secondary. I did a thousand Women in Comics panels before I was ever asked to discuss my work as an editor on any convention panel anywhere.

And then … as a woman, once you turn 60, you’re invisible. No one notices you anymore anyway. Senior women just disappear altogether from most people’s radar, certainly from most men’s.

Relatedly, and mindful of your experience, can I ask your opinion of how women are treated in general in the comics industry?

I retired from my editorial staff position at Dark Horse in 2015, so I’m not involved in the day-to-day of publishing anymore, and can’t really speak to the present other than what I read on various news sites. But I think that the revelations about Dark Horse’s former editor in chief, Scott Allie, are pretty indicative of the kind of thing that can go on, and has gone on, behind closed doors for far too long.

My very first day of work in comics, way back in 1978, I heard someone ask the owners, Who’s the skirt? Well, when that’s the starting point, you know it can only get better.

Right?

Can you describe the duties of an editor in chief? Say, a picture of an average day in the role?

Well … hmm. First, I have to say that the role of editor in chief differs from company to company, and even within a single company it morphs over time. At Comico, I was editorial coordinator in 1985, overseeing the schedules, then editor in chief from 1986 through 1989, overseeing everything. At Dark Horse, I was managing editor in 1991 and 1992, then editor in chief from 1994 to 1996. Man, I hope I have those dates right! It was a long time ago. As editor in chief at Dark Horse, the first thing I was asked to do was drop almost all the books I was editing. I hated that!

There was nothing I loved more than getting my hands dirty, so to speak, making books. We’re talking 30 years ago now, so my memory has faded over time, but in those years Dark Horse was growing dramatically. As I said, it had been a company of only 10 people when I’d started there, in 1990. But four years later, we had over 40 employees—and that’s when the toilet paper started disappearing, know what I mean? We’d reached the threshold where I guess people began seeing the company as something alien, something it was okay to steal from. Whereas I’d started when Dark Horse was so small that it felt like family, if dysfunctional at times. But suddenly we were growing fast, and I got saddled with constant personnel issues. In fact, that seemed to be the primary role of DH’s editor in chief: the hiring and firing of editors, personnel issues that just felt oppressive and not at all what I wanted to do.

Scheduling was suddenly my responsibility again, so I asked Bob Cooper—an experienced systems analyst who’d previously been my assistant editor—to oversee all the individual book production schedules along with the Master Production & Printing Schedule for the entire company, meaning that I effectively created the new position of editorial coordinator. Pretty sure Coop hated that job, but he did it to help me out, god bless him.

To tell you the truth, it was all so long ago that I really don’t remember what the day-to-day was like. One crisis after another! Countless mind-numbing meetings, umpteen memos every single day, and not being able to work with creators to make books, which was something I was pretty good at and really loved. Because of the company’s growth, I did restructure the entire editorial department, creating the editorial levels still in effect there, which I modeled on DC’s: assistant editor, associate editor, full editor, senior editor. Later, senior executive editor was added to that scale. This was just before the advent of email and a few years before the internet came along to completely change all the methods of comics production and all our work lives in the process!

But editor in chief usually just means you oversee one department of many within a company—the editorial department. I had very little say in publishing decisions or in developing the company’s editorial vision as a whole or in any real planning for the future—which I think is what most people associate with being editor in chief. But at Dark Horse it is (or was) a middle-management position that involves dealing with personnel issues; representing the editors as a group in interdepartmental negotiations over who is responsible for what within the company; structuring the department itself, both internally and in its external relations, in a way that makes sense and allows for individual goals and upward movement. It’s all pretty far removed from actual editorial work—it’s managerial work. And a bureaucrat I am not!

Yeah, I really did not like that job. Finally, I just stepped down after two years, took a big pay cut so I could go back to editing books, working one-on-one with creators instead of other editors. Though for a long time, I continued to be the person who trained all the junior editors coming in to Dark Horse.

It sounds like you enjoyed producing comics more than the business side of things. Was there one comic, or comics series, that made you especially proud?

Well, every editor is a businessperson. I mean, publishing is a business, and a good comics editor must have a knack for that as well, not just for story and art. Here’s an example: the design of a cover—including the artwork, the logo, and its color—is dictated not only by aesthetics but also by marketing considerations. A good cover is one that sells the product, and that can be independent of the beauty of the art itself. So, working with my designer—typically, the multitalented Cary Grazzini—to determine the right cover art along with a striking cover design for the art is both a creative and a business challenge, and it’s that unique blend of the two and the command of those two skill sets that characterize strong editorial work.

Scheduling is another important aspect of the publishing business, especially periodical publishing, and that was always interesting to me, too: making a production schedule for an individual series that can hit printer deadlines and on-sale dates while still accommodating all the individual artists involved and their specific scheduling needs, without alternately squeezing them or giving them so much time that they can’t make enough money—that’s a challenge. And it can be fun. It’s like solving an intricate, creative puzzle.

To say I “enjoyed producing comics more than the business side of things” really isn’t correct, because producing comics means actively being involved in the business side of things! Not many people really understand what editing encompasses—and, in particular, how much of that job requires a head for business. Last year, at Portland State University, I taught the first-ever (anywhere! anytime!) university-accredited course in Comics Editing, and I guess my students thought we were going to spend 10 weeks talking about story and what makes a good one, when, in fact, before we even got to that, we first had to spend several weeks talking about things like negotiating contracts, work-made-for-hire vs. creator ownership; scheduling and deadlines; order solicitation, advertising, and marketing comics; production and design; and budgeting. My students were surprised just how much math they’d be expected to do as editors! Editing is often referred to as an “invisible art,” but I think that just means people don’t know what the hell we actually do, since so much of it is behind the scenes.

As for the comic I am most proud of … all of them? I mean, that’s a little like asking which child is your favorite! I can’t really pick a favorite, Paul, but I’ll tell you about a few that I’m proud of for different reasons.

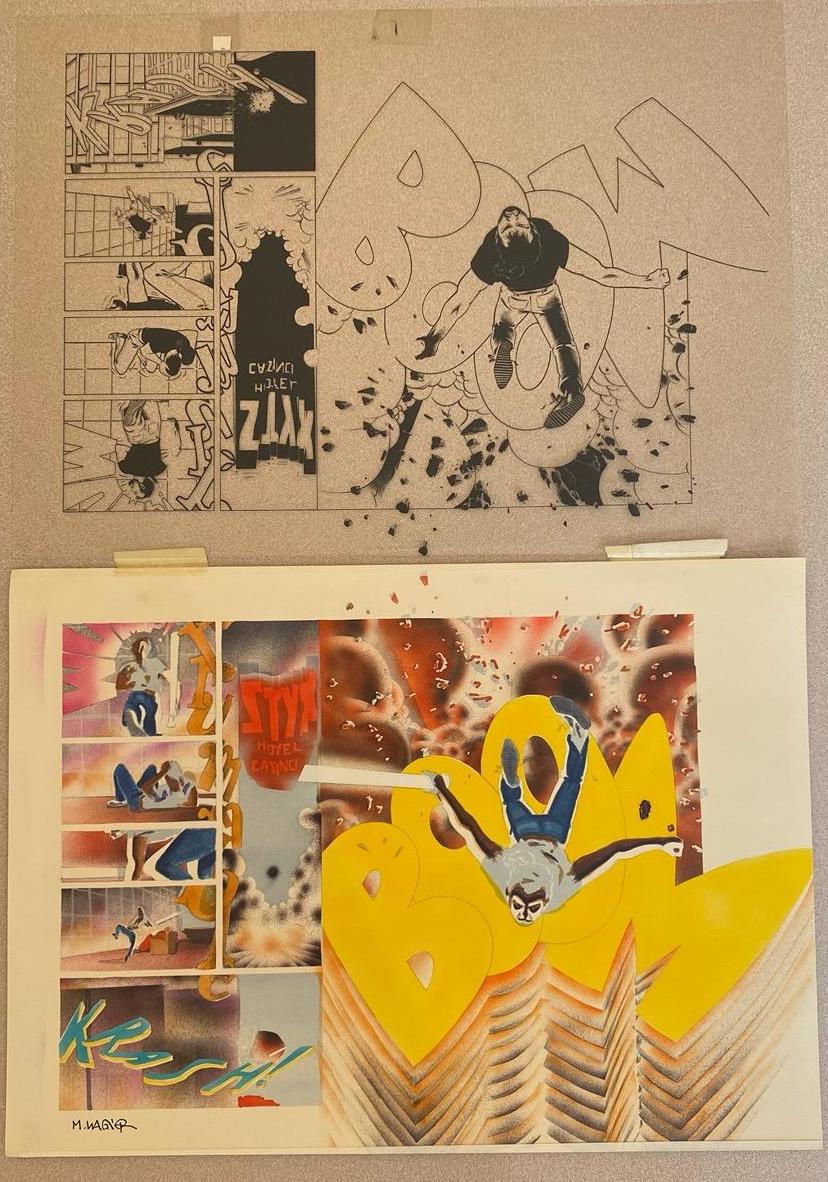

Well over 20 years ago, I came up with the idea to do Dark Horse’s first art book, and that was The Art of Sin City. I was used to editing serialized comics, mostly, and I didn’t honestly know what I was doing, but Frank Miller sent me tons of his original inked pages, pencils, and production sketches, and designer Cary Grazzini and I went to work assembling that book, which launched an entire line of art books at Dark Horse that continues to this day. And making that first Art of Sin City book was so much fun that even though I was a novice at art books, I kept going and learning more along the way, eventually adding Usagi Yojimbo, Grendel, Will Eisner, and Denis Kitchen to the list. I was lucky to have Cary help me because he’s a fantastic designer. He’s taught me an awful lot through the years.

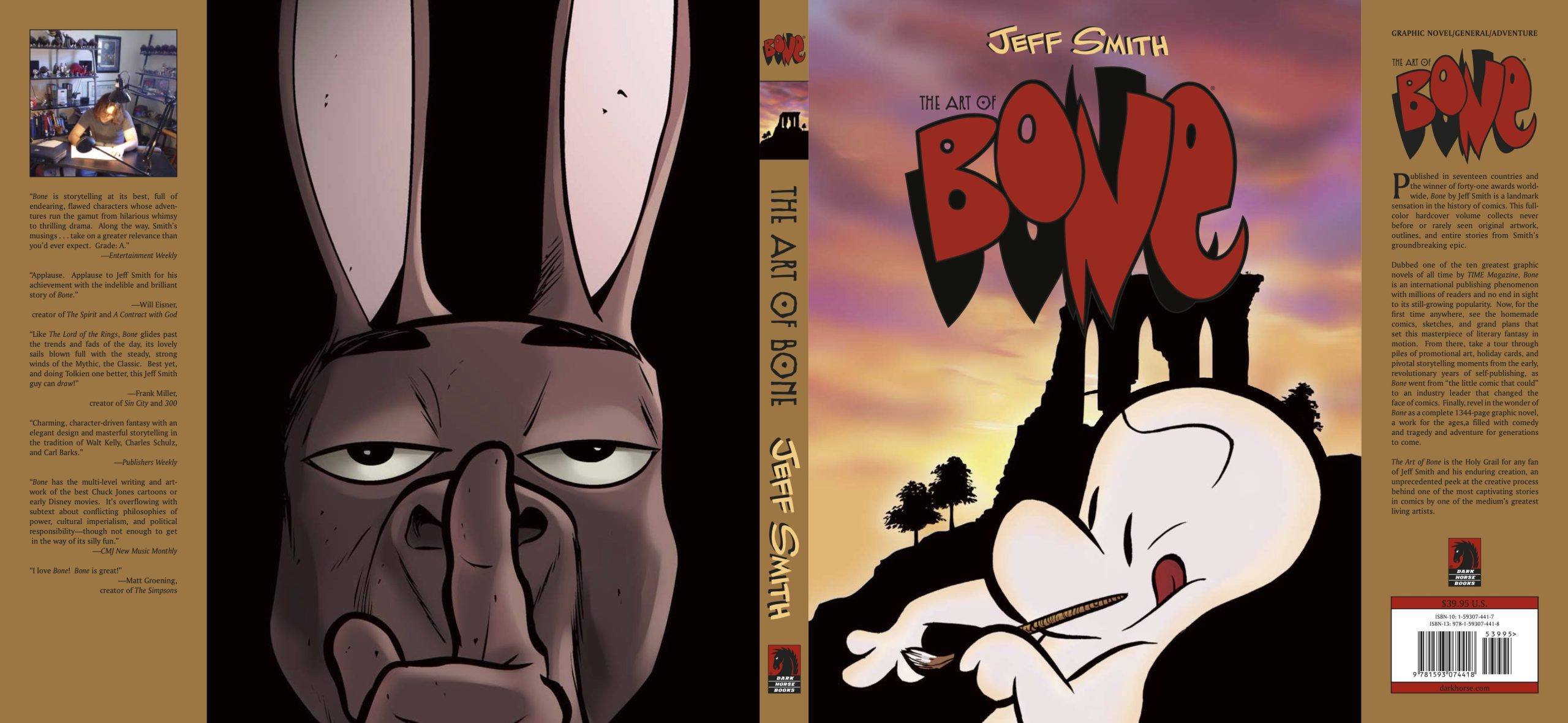

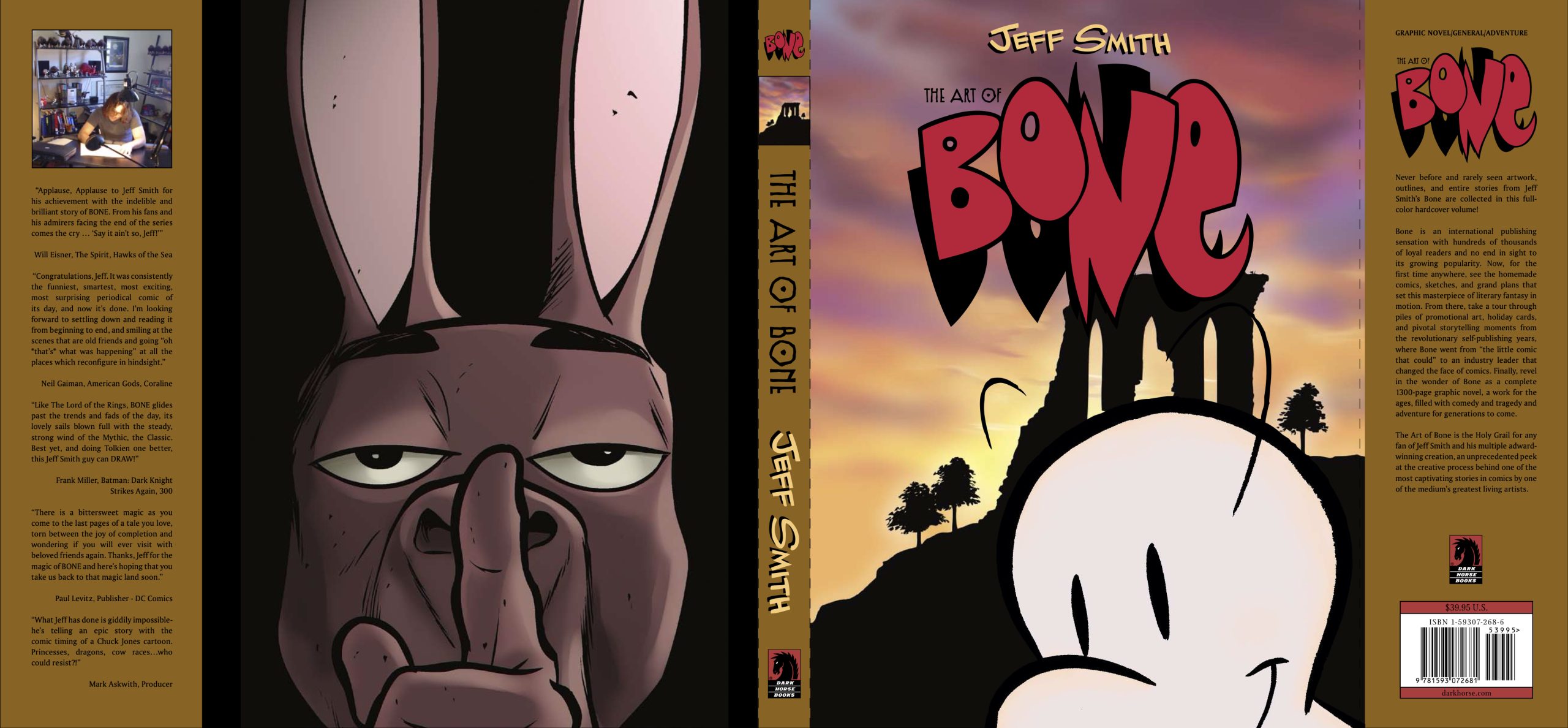

In 2007, Jeff Smith let me edit The Art of Bone, which Dark Horse published even though Bone was not a Dark Horse comic book. But I’d been a fan of Jeff’s work right from the start, and a friend, and what a joy it was to fly to Columbus, Ohio, and spend a few days at the Cartoon Books studio, looking through all of Jeff’s original drawings for Bone, some dating way back to when he was just a kid!

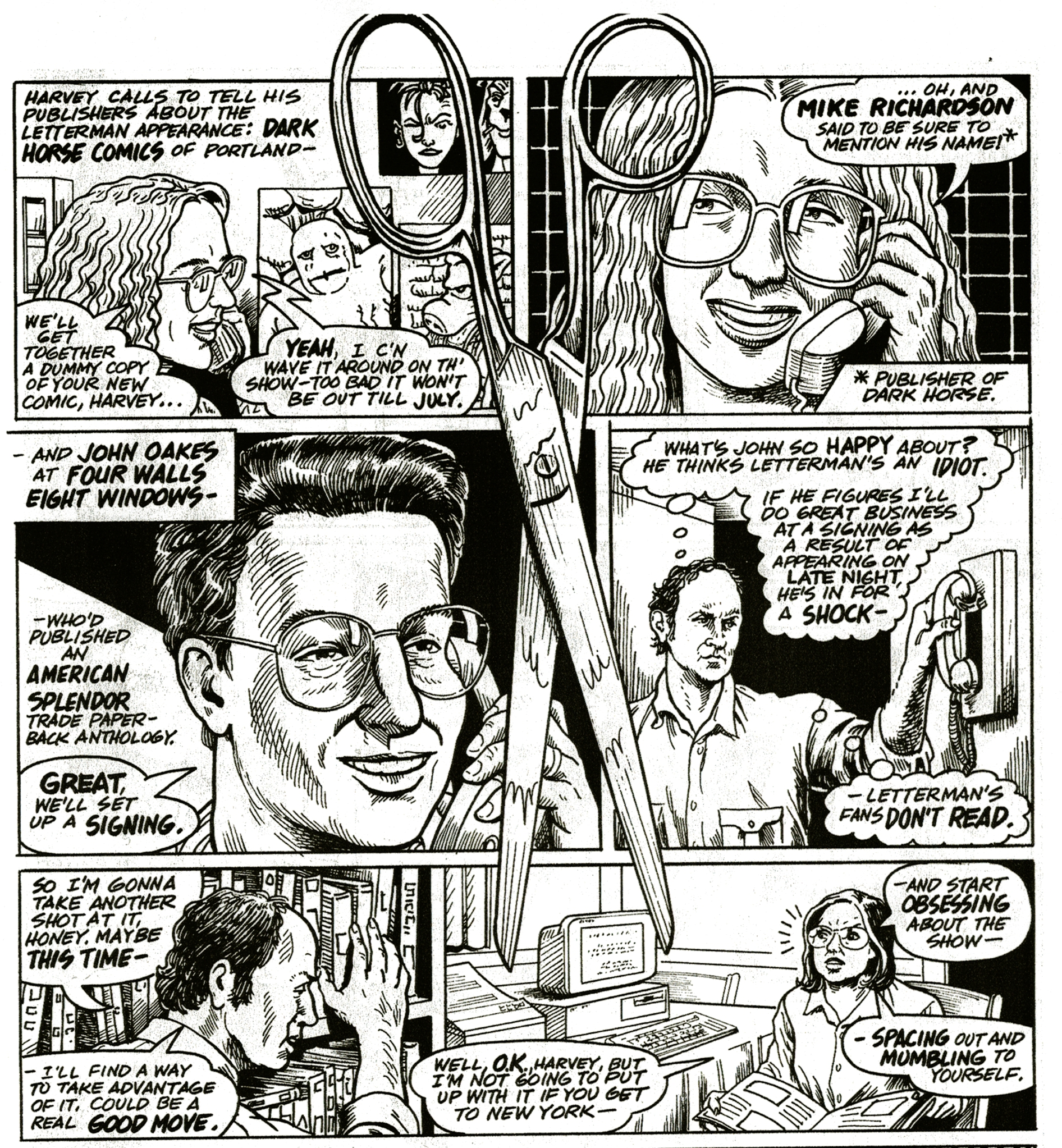

Not many people remember this, but I was Harvey Pekar’s editor on American Splendor from 1992 through 2003. Harvey began self-publishing American Splendor in 1976, but by the early ’90s, he’d been through his first cancer and it had left worn him out, so he didn’t want to handle the business end of publishing anymore, especially distribution. He and I had met several years earlier, and he knew I loved the comic, so he called and asked if I had an interest in publishing it. Even back in those early days, Dark Horse had a budgeting process for each new project, and I suspected that, given Harvey’s then-sales, American Splendor probably wouldn’t get past the accounting department. But here’s the advantage of working for a privately owned company as opposed to a corporation: I appealed to my boss, Mike Richardson—Dark Horse publisher, founder, and owner—telling him we’d been offered American Splendor and we had to publish it, sales notwithstanding. And Mike agreed! He said, and I will always remember this, “American Splendor is too important a book to say no to Harvey. He’s expanding the boundaries of the medium with his work, and I don’t care what the sales are, Dark Horse will publish Harvey’s book.” I love autobio comics, and I loved working with Harvey, so American Splendor is a bright spot in my career. For similar reasons, I loved working with Eddie Campbell, especially on his autobiographical The Dance of Lifey Death, another high point for me. Well, I love Eddie, period. He’s a good friend.

Working at Dark Horse also made it possible for me to indulge my passion for Franco-Belgian bande dessinée. I grew up in Montréal, and my elementary education was entirely in French, even though we spoke English at home. My late parents were first-generation German and Ukrainian immigrants to Canada, and it was clear to them that their three English-speaking daughters needed to learn French in what was quickly becoming a majority French-speaking city (Montréal) and province (Québec). And though I railed against my mum and dad back then, I am so grateful now that I did learn to speak French, fluently, as a child. In addition to instilling a receptivity in me for other languages—Spanish, German, Italian, even Latin, all of which I’ve studied—ultimately it opened up my own reading choices to a world of literature and allows me, now, to work as a professional translator of French and Spanish graphic novels, work that I enjoy immensely.

Along with the Jim Mooney-drawn Supergirl stories (at the back of Action Comics), my other favorite comic as a kid was Tintin, which I read in its original French. And that love of Franco-Belgian bédé continued into my adult years: so, trips home to visit family always meant returning to the US with a stack of new European graphic novels to read, or new to me at least.

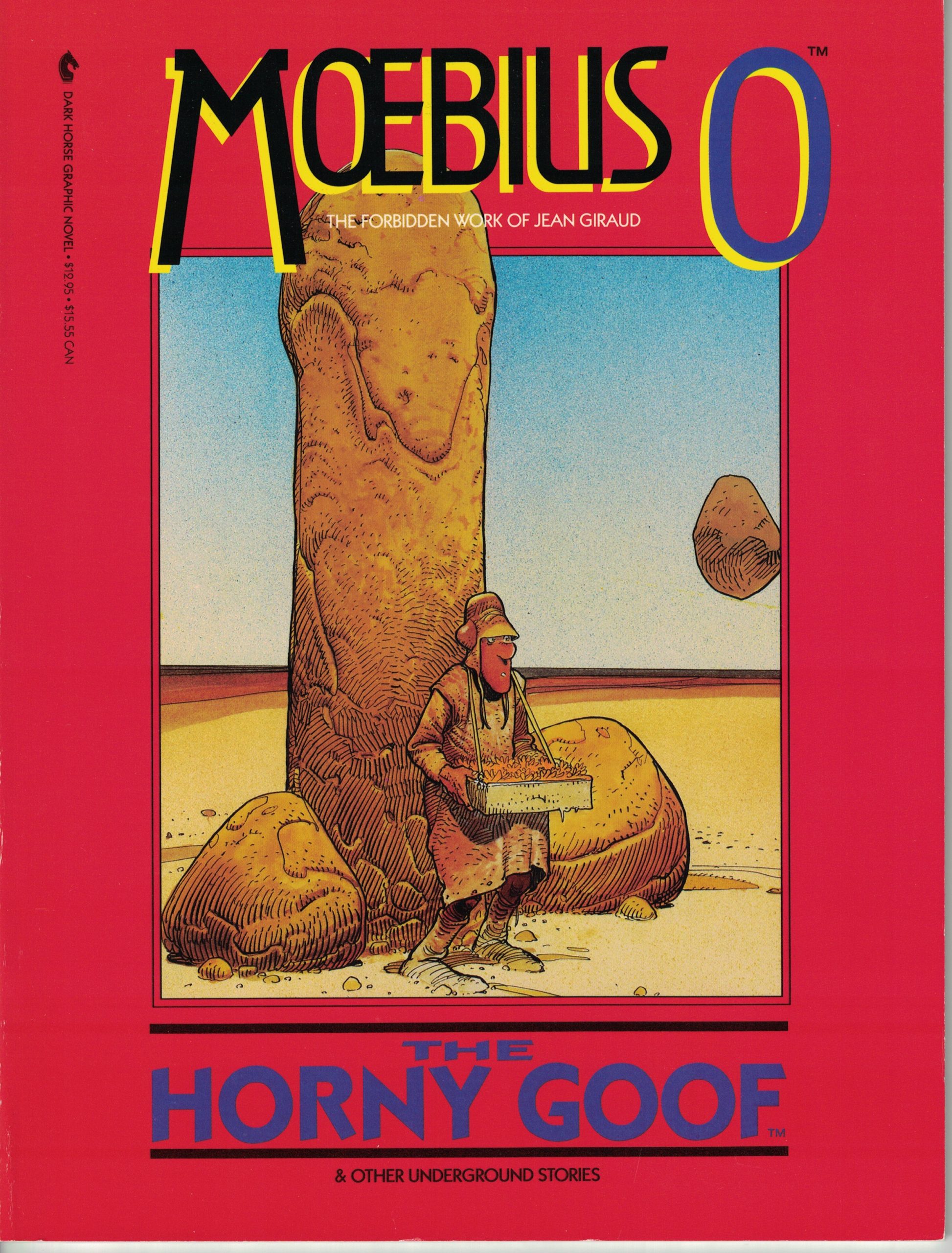

In addition to Aliens vs. Predator, one of my very first gigs at Dark Horse was Moebius 0: The Horny Goof. Marvel was publishing their series of Moebius graphic novels through Archie Goodwin’s Epic imprint, but The Horny Goof was a collection of Giraud’s more underground-style work—so it was very sexy and really out there, and Marvel refused to touch it. I mean, there was a big erect stone dick right on the cover! Anyway, editing that English-language translation of Moebius’s more raw, bawdy humor was a blast! Who knew I’d be translating his work now!

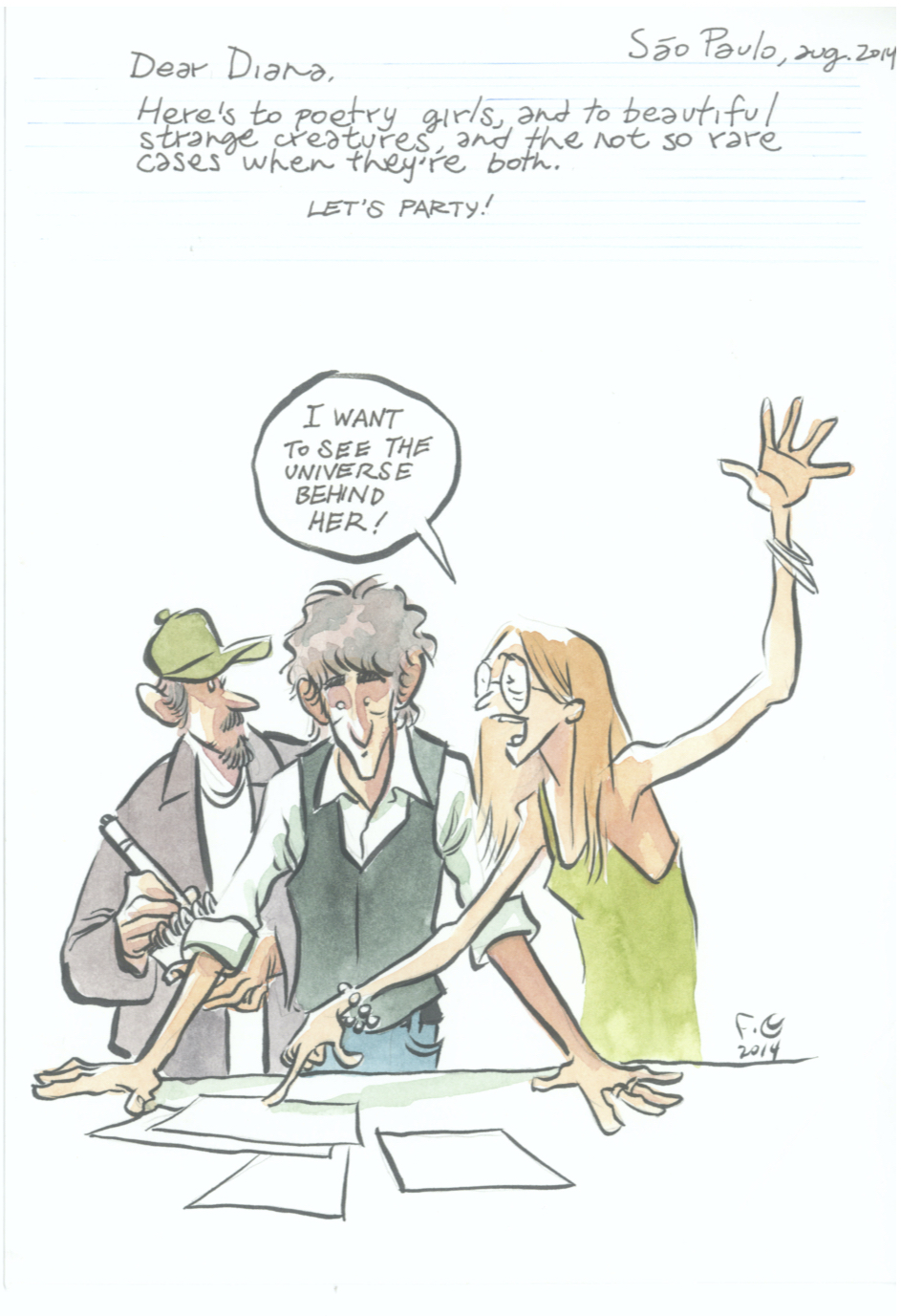

Jacques Tardi is another favorite of mine, and no one remembers this, but in 1992 Dark Horse published The Secret of the Salamander, one of Tardi’s Adèle Blanc-Sec books, as a 48-page black-and-white comic book—a joy for me to edit! And somewhere along the way I’d discovered Marc-Antoine Mathieu, a brilliant French cartoonist best known for his mind-bending, groundbreaking Julius Corentin Acquefacques series of graphic novels, whose stories are filled with inventive formal tricks and intricate wordplay, making them almost impossible to translate—but I convinced Dark Horse to try just the same. So, in 2003, we published Mathieu’s Dead Memory (“Mémoire morte”), translated by Helge Dascher. Sadly, that book was too far ahead of its time for American readers, I think. European graphic novels were still struggling in those years, and sales just couldn’t support continuing with Mathieu’s work. But slowly, through the years, US audiences have become more and more open to European work: witness the huge success of Blacksad, which I began editing for Dark Horse with A Silent Hell in 2012. In fact, as of the most recent book, Blacksad: They All Fall Down—which I translated with my partner, Brandon Kander—creators Juan Díaz Canales and Juanjo Guarnido talked me back into editing the English-language editions again. Temporarily, anyway.

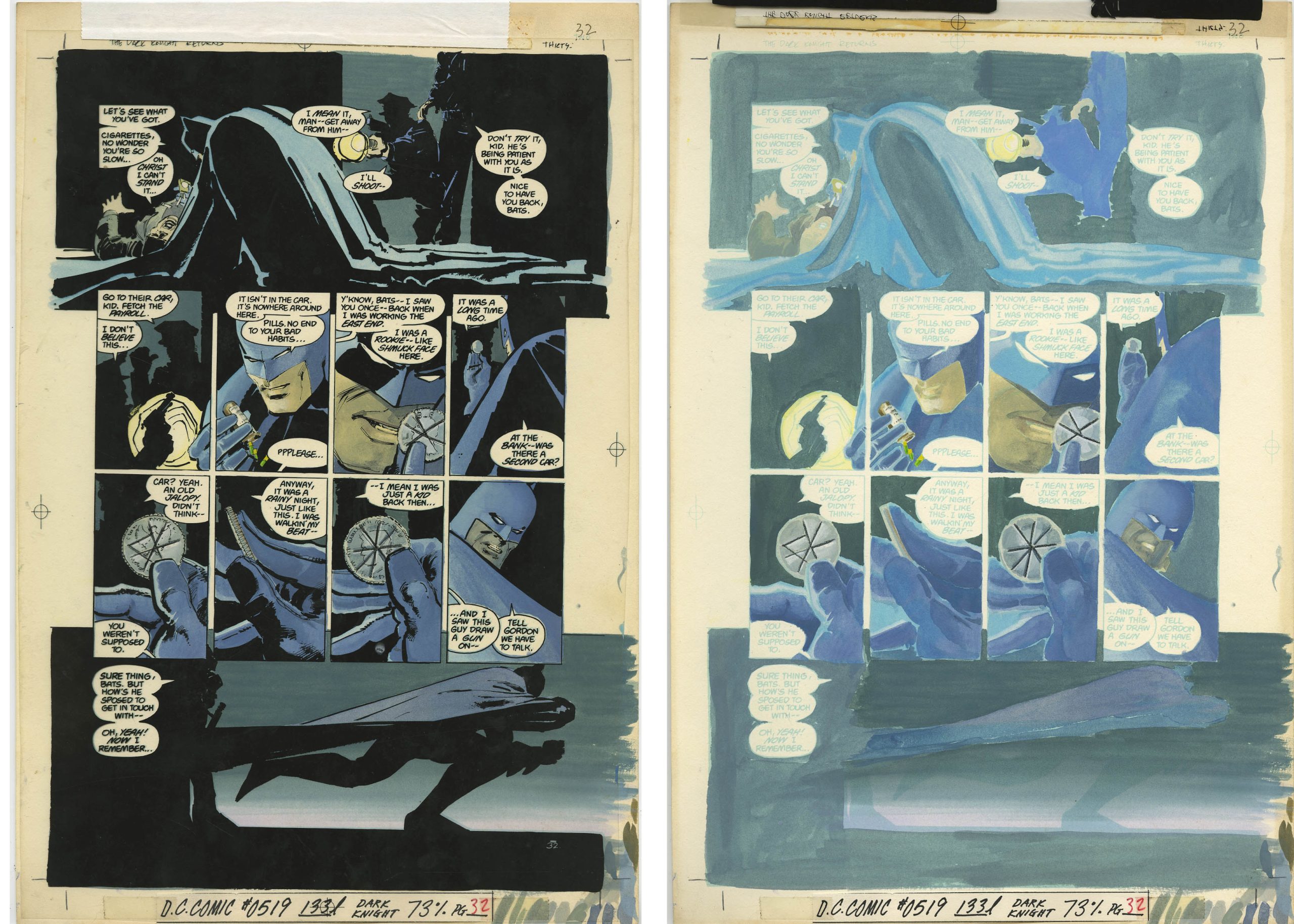

When asked about books I’m most proud of, I’d be remiss if I didn’t talk about 300, the five-issue series and subsequent landscape hardcover graphic novel, by Frank Miller and Lynn Varley. I don’t think I’ve ever worked harder on a project than on 300. Lynn revolutionized color in comics here in the US in the 1980s, something she’s not given nearly enough credit for, but she’s largely responsible for introducing blueline color painting to mainstream comics with Ronin in 1984 and especially with Batman: The Dark Knight Returns in 1986. Anyway, blueline color is a complex technical process—that I won’t even try to explain—allowing the color artist to hand-paint each page while still preserving the crisp black line on its own separate level for printing, undiluted by the surrounding color. Lynn had learned this method in France from Moebius, and by 1986, my brother-in-law Matt Wagner was also using it on Mage.

Meanwhile, so-called “flat” color was trying to keep up with the expressiveness afforded by painted color, especially as we were printing on whiter, less porous paper. By 1987, for example, Comico had teamed with veteran artist Murphy Anderson and his Visual Concepts color separation house to develop additional black tones in the 10% and 20% ranges, resulting in the number of available flat or “coded” colors to increase from 124 (I think it was) to 372. And then, of course, Dark Horse hired young Matthew Hollingsworth to create our in-house digital color department; this was in the pre-Photoshop days of Tint-Prep, very early comics coloring software. So, by 1997, when Frank, Lynn, and I began working on 300, every day had felt like a new crash course in comics color, because things were changing that quickly.

With 300, Lynn wanted to try something new: a blackline process. This meant printing Frank’s original black-and-white artwork at reproduction size onto watercolor paper, which Lynn would then paint. At that point, Frank had begun drawing at twice the size of reproduction, which is quite a bit larger than most comics artists draw their pages, and because each issue of 300 was composed exclusively of double-page spreads, his original art for the series was just HUGE! We needed a local printer who could make the blacklines for Lynn to color, and just finding one, first of all, was a challenge. I needed that printer to provide me with 5–10 black-and-white copies of each spread, printed pristinely on good-quality watercolor paper—again, at reproduction size, the final size of the comic book, in other words. Once I received Frank’s art for each issue—which he FedExed in just massive packages—I would read the issue immediately, which Frank always insisted on. Then I’d read it a second time for proofing, have any necessary art or lettering corrections made—after having discussed those first with Frank, of course—and surrender those original inked pages, now corrected, to that local printer to create the 5–10 black-and-white reproductions on flexible watercolor board for Lynn to paint. In fact, I’m pretty sure I even had to supply the art board; I sort of remember shopping for that because no printer would just happen to have the very specific flexible watercolor art board in stock that Lynn needed. Anyway, once painted, Lynn’s color art would be scanned, and the lettering would be dropped out of the four-color process, eventually to be reinstated on the black plate only, to prevent any blurring.

And it was right at that point that comics printing began to transition from a film environment to a digital one—by which I mean that comics, just like old photos, used to be printed from film negatives, but towards the end of the 20th century, digital took over: though mechanical (or “flat”) color had already begun the shift into digital color files, we were still outputting those files into film negs and physically stripping them up into eight-page flats for the printer. But then comics printing itself began to fully inhabit a digital environment: as printing tech also became digital, negative color film became obsolete, and printers began printing directly from digital color files. Well, Miller and Varley’s 300 series arrived smack in the middle of that entire transition! And while we were all learning how to negotiate this new reality, Lynn was hand-painting each spread, using watercolor on the “blackline” pages. There were 13 of those spreads for each issue, so 13 paintings for Lynn, except the last issue, which was double-sized. Incidentally, the reason Lynn wanted multiple copies of each spread was to allow herself as many attempts at the color as she needed before deciding on the final one to submit. She’s a perfectionist! We all are!

I’ve said this many times, but I’ll say it again here: when Lynn’s first issue of watercolor art for 300 arrived on my desk … I wept. That incredible beauty … the sensitivity of her watercolors was just overwhelming, bringing me to tears. That is the power of real Art. Incidentally, Zack Snyder would go on to mimic Lynn’s color palette shot for shot, scene for scene in his movie adaptation of the 300 graphic novel.

But having that gorgeous art in hand and getting it to reproduce faithfully in the comic books were two different things! And I worked my ass off on that. In those days, flatbed scanning wasn’t yet technically advanced enough to do a high-quality job, and we were still outsourcing painted color for scanning. So, I hired a local scanning outfit that had been recommended to me: Lynn’s flexible watercolor boards—this is why they had to be flexible—would get wrapped around big circular drum scanners, and each scan became a digital file, which was then output as a positive film proof for me to approve. Which is to say I mostly disapproved each scan until Lynn’s color was absolutely perfectly reproduced! But the clock was always ticking, and a few particularly tough scans meant I had to go to the scan company office a few times myself. This was 1997, 1998, and it was my first time seeing painted color scans manipulated onscreen—for those last-minute approvals. I remember one scan in particular giving us so much grief that we were up to the 17th correction before I finally caved and okayed it. But Lynn’s color was so beautiful, how could I do anything less?

Printing was yet another challenge because … well, color (especially painted color) sort of migrates on the press, and when you have predominantly blue pages printing near to predominantly red pages, it’s hard to keep the colors coherent, to keep them from invading each other. We sent our print buyer, Darlene Vogel—god bless her and her exceptional eye—on press, all the way to Singapore, for a few printings of the graphic novel, and she would literally stand there, telling the printers to up the blues here, pull back on the reds there, and so on. During the very first printing, she called me at home in the middle of the night, whatever time it was in Singapore, to make some judgment call that I no longer remember. But that’s just what you do when you’re invested in a project and you want to make it work. You want to make it work for the creators, because your job as an editor is to realize their vision, but you also want to make it work for the readers. You want the reader to see what you see: the talent, the artistry, the miracle. Frank and Lynn gifted me a color version of the final page of the graphic novel, the last spread of issue #5, and when you see it, the color is just so lush that you’d never believe it’s one of Lynn’s “rejects”!

In the end, Paul, I mean … I worked with giant talents like Will Eisner, Neal Adams, Barry Windsor-Smith. I worked with brilliant writers like Neil Gaiman, Harlan Ellison, Brian K. Vaughan, Pulitzer-winner Michael Chabon. I worked with the heroes of my youth, Jim Mooney, Murphy Anderson, Carmine Infantino, and my adult heroes the Hernandez Brothers. I worked with my contemporaries, exceptionally talented cartoonists and independent spirits like Larry Marder, Shannon Wheeler, Stan Sakai, Paul Chadwick, and, right from the start, my amazing brother-in-law Matt Wagner. I discovered young, new talents, like the late, much-missed Tim Sale, way back in the mid-1980s, and then over a decade later, my amazing Brazilian twins Fábio Moon and Gabriel Bá. I am as blessed an editor as ever could be. It’s impossible to tell you what I’m most proud of, because it’s all of it.

Any memories of the Give Me Liberty comics?

The four-issue prestige format Give Me Liberty, by Frank Miller and Dave Gibbons, began production in 1989, the year before Dark Horse moved Bob Schreck and me to Portland, so I wouldn’t actually end up editing the various Martha Washington series until Martha Washington Saves the World, sometime in the mid ’90s. Of course, Frank and I had met way back in Berkeley, California, in 1981, but I didn’t become his editor until 1997. I probably met Dave in the late ’80s, though I remember being very surprised when he asked me to edit the 1991 Batman vs. Predator series, which he was writing, with Andy and Adam Kubert on pencils and inks. The thing about Give Me Liberty … y’know, the ’80s were such a political time in comics. The industry was so much smaller then. For example, when I first started going to the San Diego Comic-Con, in 1982, there were only about 4,000 of us there—compared to today’s 130,000! So, it was easy to get to know people personally, much easier than it is nowadays, I think, despite the internet and social media. Also, there were very few women working in comics—at any level. You’d see the same handful of us, over and over again, at every Women in Comics panel at every convention! And in those years independent publishers were just beginning to establish themselves as an alternative to Marvel and DC. When Frank and I first became friends, in 1981, Dark Horse didn’t even exist—and wouldn’t for another five years!

But up until the advent of independent publishing—with Mike Friedrich’s Star*Reach laying the groundwork in 1974, followed by Fantagraphics and Eclipse solidifying the structure in ’76 and ’77—if you wanted to work in the comic book biz, you had to sign away all your rights. Period. Typically, as an artist, you were paid a one-time crappy page rate—for penciling, or for inking, or for creating Superman! As a penciler, say, you weren’t given any choice over who would ink your work. If the work was reprinted, you weren’t paid anything extra. If you created a new character that became popular enough to warrant its own series or any kind of ancillary item—movies, lunchboxes, action figures, whatever—you didn’t get paid anything extra for that either. Comics creatives were being exploited by Marvel and DC in ways that were unconscionable, simply unethical, and the companies had been getting rich on the backs of creators for decades! Artists didn’t even get their own original, physical artwork back until sometime in the mid-’70s, I believe, and then only because Neal Adams began rallying creators to petition for their rights. Comics fans of today—and even creators—either have forgotten all this or don’t even know about it to begin with, but independent publishers arose as a reaction against Marvel and DC and their repressive policies. Jack Kirby, in particular, had been really fucked over by Marvel, his original artwork stolen or given away to cadge favors—or just utterly neglected and left to rot in some storage space where it was never recovered, if you prefer to believe that. And by the ’80s, other artists began getting vocal about art return, reprint rates and sales royalties, ownership and creators’ rights overall, especially in support of Jack Kirby. People like Neal Adams and Frank Miller were out there leading the way, along with Gary Groth and The Comics Journal. And independent publishers—like the ’70s pioneers, and then in the ’80s Pacific and Comico and eventually Dark Horse—were founded on the principle of creators’ rights. But most of the work they published back then was in black-and-white and by novice creators—Love and Rockets by the then-unknown Hernandez Brothers, for instance. And sales couldn’t really begin to compare with those of the so-called Big Two, Marvel and DC. But economies of scale notwithstanding, the independent movement, and it was a movement, was growing.

So, imagine: fresh off the enormous success of both Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and of Watchmen, when Frank Miller and Dave Gibbons, who had only worked before on characters they did not own, decided to team up for a new creator-owned project in 1988, then opted to bring that new project, Give Me Liberty, to the tiny, three-year-old, black-and-white publishing “company” in Nowheresville, Oregon … man, that was huge! Both Frank and Dave had been talking the talk, as it were, but then they also got up and walked the walk, putting their money, their livelihood, directly on the line, standing up for what they believed in: creators’ rights. Taking Give Me Liberty to a then-upstart independent young company like Dark Horse rocked the comics industry in a way that changed everything.

During your time in the comics industry there have been significant advances in computer technology that have altered the way comics are produced, printed, and consumed. From an editor’s perspective, what do you see as the most significant advantages and disadvantages of these changes?

The computer itself is the most significant technological advance that I’ve lived through. I’m old enough that I was 35 before the personal computer became an essential part of my work as an editor. At Comico, we had one of those old box-like Macs for the entire office, and I never used the damn thing—I was afraid of it! But it was clearly the wave of the future, so in 1988 and 1989 I took community college night courses in what was then a growing academic area: Computer Science. And in 1990, when Bob Schreck and I began working at Dark Horse, the company provided us with our own Macs, so I’m glad I’d learned to use one by then. But I was almost 40 before I bought one for home use. I’ve always done a lot of work at home; as an editor, the work doesn’t end just because it’s 5 o’clock, and if you’re conscientious, you take the work home to get it done. In fact, I always got more work done at home because of the lack of interruptions.

Dark Horse didn’t get email, though, until 1996. So, in my years of editing The Telegraph Wire retailer zine for Comics & Comix, then in all my time at Comico, and for the first six years at Dark Horse, the phone was my primary editorial tool. Which means I talked to my freelance creators in person over the phone at least once a week. Nowadays people use their phones for everything … except speaking to someone! And from an editorial perspective, I believe that’s a tremendous disadvantage. First of all, it’s pretty hard to chase deadlines via email. Emails and even texts are a lot easier to ignore than your editor’s voice over the phone. More importantly, email doesn’t really build the kind of personal editor-creator connection that you develop over time by speaking to someone directly. And if you’re not interested in creating those trusted working relationships, then editing is perhaps not the job for you.

As for reading comics on a screen … well, I don’t do it. No doubt because of my age, but that just feels like work to me, not pleasure, and I still derive, and want to derive, pleasure from reading comics. I know so many editors whose passion for comics has burnt out as a result of the job. There’s a comics shop right across the street from the Dark Horse editorial offices, and when I was still on staff, I was one of very few editors who still checked out the new comics each week—and not out of a sense of duty, but because I love the form. At 68, I still shop at that LCS, and I still read comics … every day! Right now wrapping up one of the Pogo volumes, which I’m admittedly rushing just a little to get to Eddie Campbell’s new flip book, one half of which—The Fate of the Artist—I’ve already read, but I’ll happily read it again.

To what extent did having the rights to publish comics such as Aliens, Terminator, Predator, and Star Wars help Dark Horse publish other titles that were a risk financially? I hope that is a fair question, but it feels right to discuss Dark Horse in particular.

It’s a fair question, Paul. And a good one, but I’m afraid the answer is Not much. Or in any case, Not directly. Dark Horse had, and still has, a standard system for budgeting all new projects. Having survived the demise of one small company, Comico, that I’d predicted would soon go bankrupt—which is the reason that Bob Schreck and I left there in 1989, after the owners refused to admit what the math had already proved to me—I really appreciated Dark Horse’s more judicious approach to costing out new projects. I’ve already told you the story of American Splendor and how Mike Richardson bulldozed that through, for reasons of quality, sales numbers notwithstanding. But that was the exception. Most books had to prove themselves financially viable before they were approved for publication. That was a complex formula of creative and print costs versus projected sales.

Where the licensed titles really helped was in expanding the company itself: hiring new editors, growing other departments. And, of course, as we grew, more projects were pitched to us, we developed more credibility, and that led to further expansion of the line. The company grew like a weed during my 25 years on staff!

How much hands-on involvement did you have on the licensed comics? For that matter, do you have a favorite?

Are you familiar with the work of my Norwegian friend, cartoonist John Sæterøy, who signs his work “JASON”? Maybe you’ll enjoy this licensed comic, which I edited and which Dark Horse published in its Star Wars Tales anthology …

There’s no doubt that Lucasfilm was in tight control of their license, but there’s a sense in which I prefer that: no matter how egregious the “rules” might seem, it’s better to have them spelled out beforehand than to learn after the fact that the licensed comic you’ve been sweating over has been disapproved for some obscure reason—which might amount to the licensing rep just having a bad day. But if you’re given guidelines to follow from the start, then you just work around them. There’s not a lot of point to fighting the licensor. They own the IP. Star Wars is George Lucas’s baby, and that’s the bottom line. So, for example, when I first saw John’s “Who’s Your Daddy” strip—as an unlicensed black-and-white bootleg—I asked him if we could make it legal by publishing it in Star Wars Tales, which was edited by Dave Land, but different editors could submit different strips for the anthology. John’s bootleg was not titled, so I think I came up with that, and then panel 3 on the first page originally had Darth Vader peeing in the sink, and as funny as that was, I knew it would never fly at Lucasfilm, so I recommended to John that he have Darth brushing his grille instead. John replaced the panel, his delightful two-pager was approved for publication, and we were able to pay him some good money! Though I cannot for the life of me remember who did the color. Maybe Paul Hornschemeier, creator of the Mother, Come Home graphic novel, another project I was blessed to edit [NOTE: Paul did].

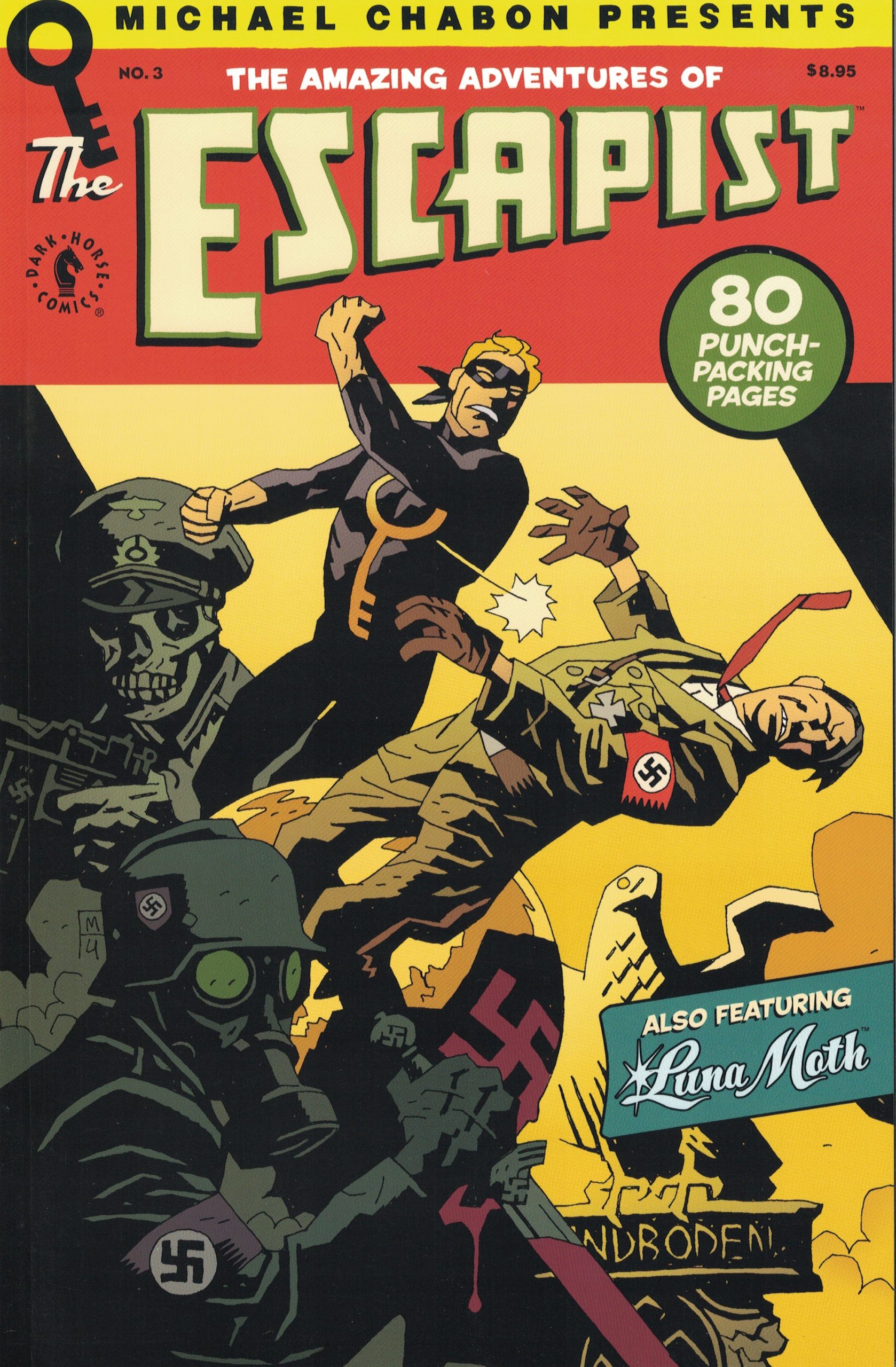

Sometimes the licensor is not a corporate entity but a single individual. I loved working with Michael Chabon on The Amazing Adventures of the Escapist, an anthology series based on an important character from his Pulitzer-winning novel, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay. And in 2005 we won both the Eisner and Harvey Awards for Best Anthology. But then, of course, the book was canceled later that year, because as quality-driven as we were, anthologies have a difficult time maintaining sales levels, especially color anthologies. And they’re a complicated juggling act for any editor!

Oh, but it was fun! I’m not sure how familiar you are with Michael’s novel, but it presents a history of comics that is in large part accurate … except for the Escapist character and its publication history, all of which sounds true but is entirely made up! And we kept up the faux history in the comic book, which allowed Dark Horse’s “resident historian,” Bubbles LaTour (me!), to write fanciful histories of the stories—about their “original” publication or about the spurious company that had “published” them or about the genre they “pioneered”! It was a lot of work, writing that meta-history for the stories, but it was worth the effort! And we matched that effort in the artwork, too. For instance, I’d asked my longtime friend, Hellboy creator Mike Mignola, to draw the cover for the third issue of the anthology— requesting a riff on Simon & Kirby’s first issue of Captain America, where Cap punches Hitler on the jaw, sending him flying across the cover. That cover was pretty controversial for its time—1941, just before the US entered World War II. Well, the way we told it, that “historic” cover had featured the Escapist, not Captain America!

Anyway, I guess the point is that just because a book is a licensed property, that’s no reason to treat it like shit. Readers may be used to thinking that way because, typically, that’s exactly how Marvel and DC tend to treat anything they don’t own. But I have spent my entire career working in independent comics, meaning the two publishers I’ve worked for never owned any IP at all—or if they did, it was a bad mistake! Witness: DH’s Comics Greatest World universe (1993) of terrible titles created by consensus.

As for a favorite licensed title … a toss-up between the six-issue Escapists series by Brian K. Vaughan, with art by Steve Rolston and Jason Shawn Alexander, with the Golden Age sequences by the late, great Eduardo Barreto, and Jonny Quest. We published the latter at Comico from 1986 to 1988: two miniseries, two specials, and 31 issues masterfully written by Bill Messner-Loebs and drawn by a Who’s Who of artists, including JQ creator Doug Wildey, Steve Rude, Matt Wagner, Tom Yeates, Al Williamson, two heroes of my youth: Carmine Infantino and Murphy Anderson, Wendy Pini, Dan Spiegle, Ken Steacy, Adam Kubert, an amazing wraparound cover by Bill Sienkiewicz as well as a sexy Jezebel Jade cover by the late great Dave Stevens—and, of course, Marc Hempel and Mark Wheatley, who would take on the monthly art as of issue #14. Jonny Quest originally aired on American TV during primetime hours in 1964, when I was nine years old, and the show was full of everything I loved: adventure, exploration, exotic lands, and science fiction.

Incidentally, that was the same year I attended my very first rock concert: the Beatles! A life-changer for sure!

As a part of your job, did you enjoy comics conventions?

The conventions, the panels, being able to see all my closest friends gathered together in one spot every year—that was great! But working the booth, not so much. And reviewing portfolios, not at all. When you’re working the show, it can be brutal: long hours, constant loud stimuli from all angles. After a while the smile stretches pretty thin on your face—cons are just not very conducive to the kind of focus you need to properly evaluate someone’s art or their story proposal especially. And y’know, people can be rude sometimes, interrupting you in the middle of a conversation with an old friend to insist on monopolizing your time. I mean, I’ve been followed into the bathroom—the women’s bathroom, by men wanting a portfolio review!

And once Hollywood took over Comic-Con, they just sorta sucked the fun—and the comics—right out of the show. In fact, my last 10 years on staff at Dark Horse, I paid my own shot to attend Comic-Con. That was the only way I could make sure I’d have time for my creators and my friends—who were often one and the same!

Any fun or funny convention stories that you are allowed to share?

One of my best convention memories is from the 2000 Small Press Expo. This isn’t particularly funny, but it’s enormously heartwarming. SPX is (or was) a small convention: two display areas and a cash bar that’s open all through the weekend—so it’s comfortable and friendly and no blaring Hollywood crap. It’s all about the comics. That year, Will Eisner was the guest of honor, and he and I had just begun working together maybe six months earlier, but we’d already become pretty close. Will was like a father to me. And in fact, I was the age his daughter Alice would have been had she not been struck down by leukemia at age 16.

Anyway, Will had been invited to SPX to present the keynote speech for that year’s Ignatz Awards—for smaller press, more alternative work. That afternoon, he had no obligations, so I brought him around the two display rooms, where new, young, more offbeat artists were selling minicomics or other very individualistic, very art-oriented, smaller-press work: more personal, more exciting work than the standard monthly commercial comics fare. Creators in the room, if I’m remembering correctly, included James Sturm, Anders Nilsen, Seth, Paul Hornschemeier, James Kochalka, Brian Ralph, Dean Haspiel. And I brought Will from table to table, introducing him to any artist I happened to know, and that was a big deal for many of the younger artists there. Will had inspired so many of them, they were in awe of him and never expected that they would meet him, let alone that he would pay attention to their art, and he was so gracious: he took the time to look at everyone’s work that day, engaging them in conversation, and of course they gave him freebies of their books—and he was just delighted by all of it! He was leaving the next morning to return to his home in Florida, and that night, after the Ignatz Awards ceremony, he told me that he himself had been really inspired that day! Meeting all those young turks and seeing their innovative work had both excited and challenged him, and he told me that, as a result, he just “couldn’t wait to get back to the drawing board!” He was so fired up by having met that new generation of comics creators. Y’know, that’s real greatness.

My final question is simple. What does Diana Schutz do these days? And what does the future hold for her? Are there any mountains left to climb?

Your last question is a really tough one, Paul. I could just be flip and say that if I knew how to predict the future, I’d be a lot richer than I am.

But the truth is that age is sobering. I was born in 1955, so you can do the math. One thing about aging is that everything takes longer than it used to, so I doubt I could work those 60-hour weeks anymore that I routinely put in for Dark Horse. But when I “retired” in 2015, I got more involved in teaching comics courses, which I’d already been doing annually since 2002. And in 2015, Dr. Susan Kirtley founded the Comics Studies program here at Portland State University, and I think I was her first hire. So, I’ve taught a variety of courses there, including Comics History, Comics Memoir, and I’ve already mentioned the Comics Editing course I created.

Retiring from the Dark Horse staff also allowed me, in 2017–2018, to work with my brother-in-law again as his script editor on the third and final part of his Mage trilogy. And that was fantastic! I mean, that final 15-issue storyline not only features my family in its pages, but Matt wrote and drew it, and his son, my nephew Brennan Wagner, did the coloring, so that was a pretty meaningful project that I wouldn’t otherwise have been able to do while at Dark Horse, since Mage is published by Image.

But, y’know, it’s “retirement” in quotes because those of us who truly love comics never really retire, I don’t think. I had done a tiny bit of comics translation while still at Dark Horse, but I ramped that up in a big way once I left staff and have pretty consistently translated a handful of French or Spanish graphic novels into English every year since—mostly for Dark Horse, but also for other publishers like Dean Mullaney’s EuroComics, for instance [initially an imprint at IDW, now at Clover Press]. Some translations I write with my partner, Brandon Kander, and some solo, so he and I are currently translating Blacksad, which I’m also editing on a freelance basis for Dark Horse, whereas I’m translating The Moebius Library books by myself since they’re just too absurdist for him.

Very few people understand just how much writing is involved in the translation process. Understanding the meaning of a foreign text is the easy part of the job—except, of course, for Moebius! But what’s always tough is choosing how to convey that meaning in English, which is a very large and very versatile language, whose functional vocabulary is five times greater than that of French. So, translation presents a new creative challenge for me. In fact, our most recent translation, Blacksad: They All Fall Down • Part One, just won the Eisner for Best US Edition of International Material, which is enormously gratifying, especially as the Eisner Committee now recognizes the creative contribution of translators with that award, and especially considering that translation is a second career for me—and as a senior no less.

So, I hope to continue translating comics into my 70s, if my health holds up, which is an inescapable concern at my age, having already lost so many friends. And though I stopped teaching this year—or maybe it’s just a break for now, I’m not sure—I’m still pretty actively involved with Portland State University’s Comics Studies program, helping to place students in publishing internships and hoping to expand those internships, as they’ve been really productive for both the students and the publishers. A lot of people helped me out when I was a kid wanting to break into comics publishing, and I believe we have a responsibility to pay that forward. My generation of comics professionals is on its way out: we are the senior generation now. And just as Will Eisner and Harvey Kurtzman and Joe Kubert and Trina Robbins, among others, were available to us when we were starting out, I think it’s important that we make ourselves available to today’s younger comics fans who will become the industry’s next generation. Amazing creators like Shelly Bond and Brian Bendis and David Walker are teaching comics courses, and it’s not for the money, believe me! They’re part of our Comics Studies program because they’re dedicated to comics and to helping shape the future of this industry that we all love so much.

If the future had nothing left to offer, Paul, then I wouldn’t be here to answer your questions. That said, being nominated and then actually voted into the Eisner Hall of Fame was both entirely unexpected and greatly humbling, a huge honor, especially among such a stellar cast of fellow nominees. Really, I consider myself incredibly blessed. I’ve been able to spend my entire adult life doing something I love, in an industry I love, with people I love, and it just doesn’t get any better than that.

The post Work and Pleasure: Diana Schutz, Today appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment