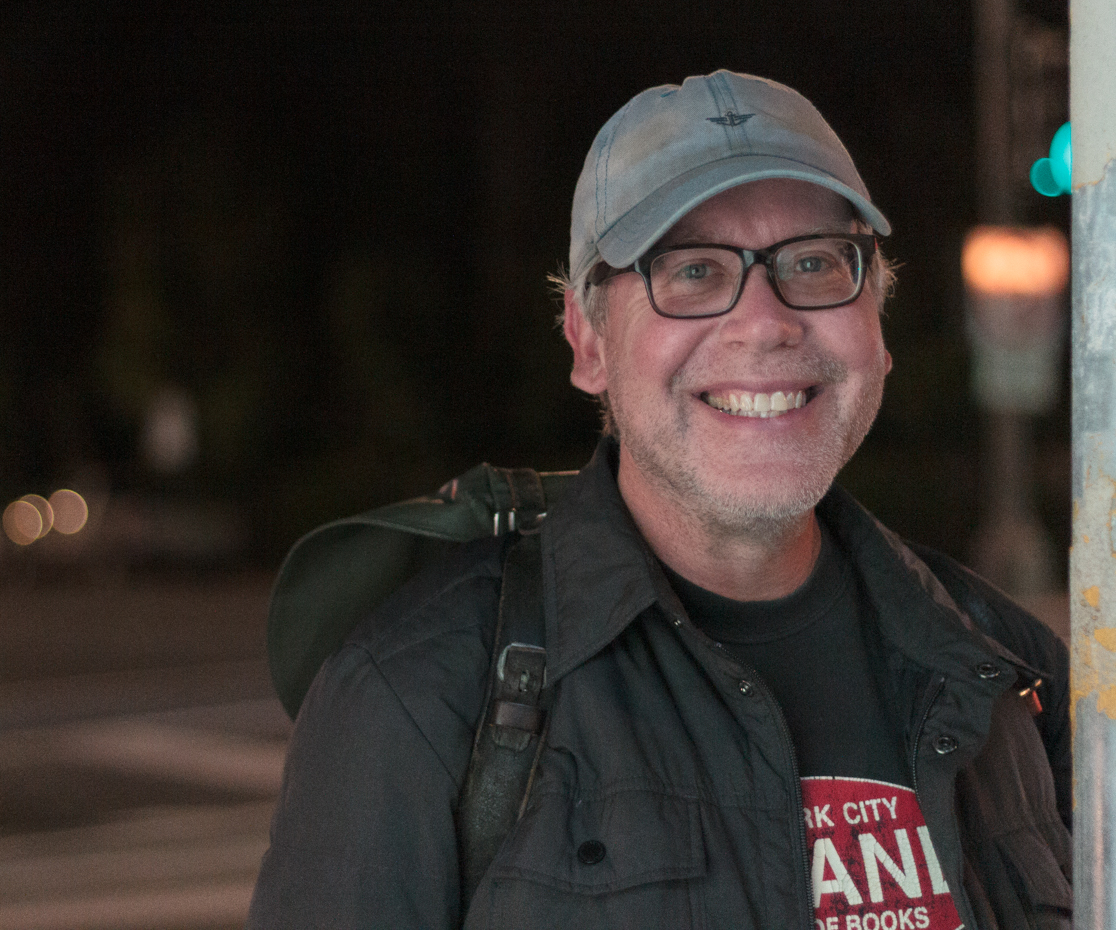

Sixty-year-old alternative cartoonist Joe Matt was found dead Sunday, Sept. 17, literally at his drawing board until the end. Matt had reportedly experienced chest pains in recent days, and while the cause of death had not been announced at press time, circumstances pointed to a heart attack.

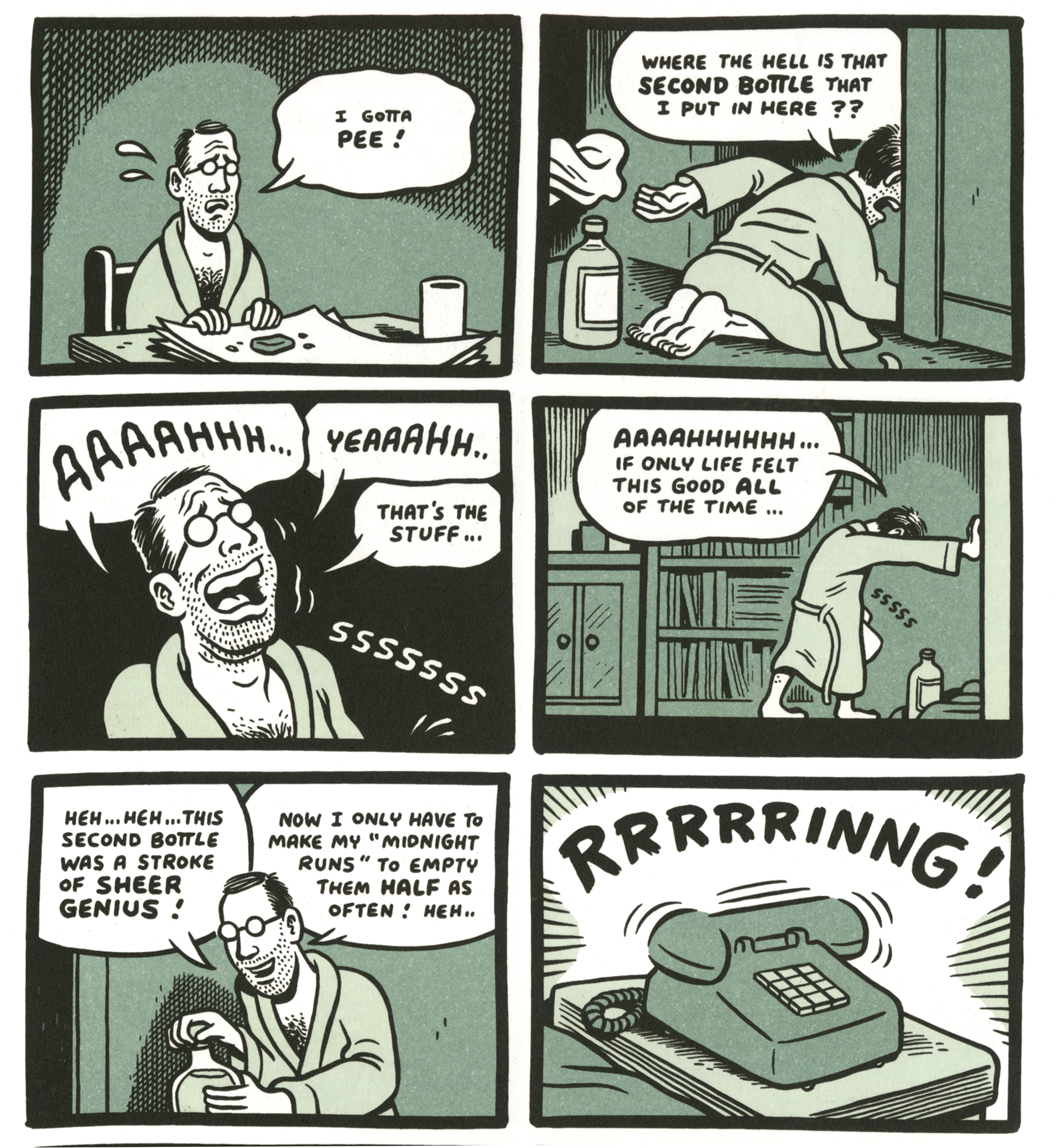

The opposite of a celebrity cartoonist, Matt had diligently recorded the ordinary, unflattering, financially impoverished, even abject, details of his life in the 14-issue Peepshow series published by Drawn & Quarterly from 1992 to 2006. The brutal honesty of his depictions followed a tradition established by Undergrounders like Robert Crumb, Justin Green and Aline Kominsky-Crumb, and in turn influenced a new generation of bluntly candid autobiographical cartoonists.

A large part of the Peepshow narrative explored Matt’s obsessions with masturbation and pornography after breaking up with his girlfriend. Both he and Crumb could be accused (especially by quick-to-cancel, post-millennial readers) of indulging their sordid male appetites on the pages of their comics — a form of masculine exhibitionism that only guy cartoonists could get away with. If it was comparatively easy to forgive Matt his storied flaws, it may have been because Crumb’s idiosyncrasies helped make him not only a great artist but relatively wealthy, whereas Matt’s long list of sins required a devotion that ensured he would forever remain a starving artist, albeit a very talented one.

Most importantly, no matter how low his self-aware persona sank, he was never allowed a moment of straight-faced drama; Matt was never not funny. If he was infuriating, he was also consistently entertaining and observant. As an artist, he didn’t have Crumb’s larger ambitions. The world he drew was organically complete — simple, cartoonish, comically paced, but rarely straying from a quotidian, matter-of-fact focus. His avatar occupied a share of the lower depths that was not so much tragic as petty — more punk introversion than, say, the grotty, beat romanticism of a Charles Bukowski.

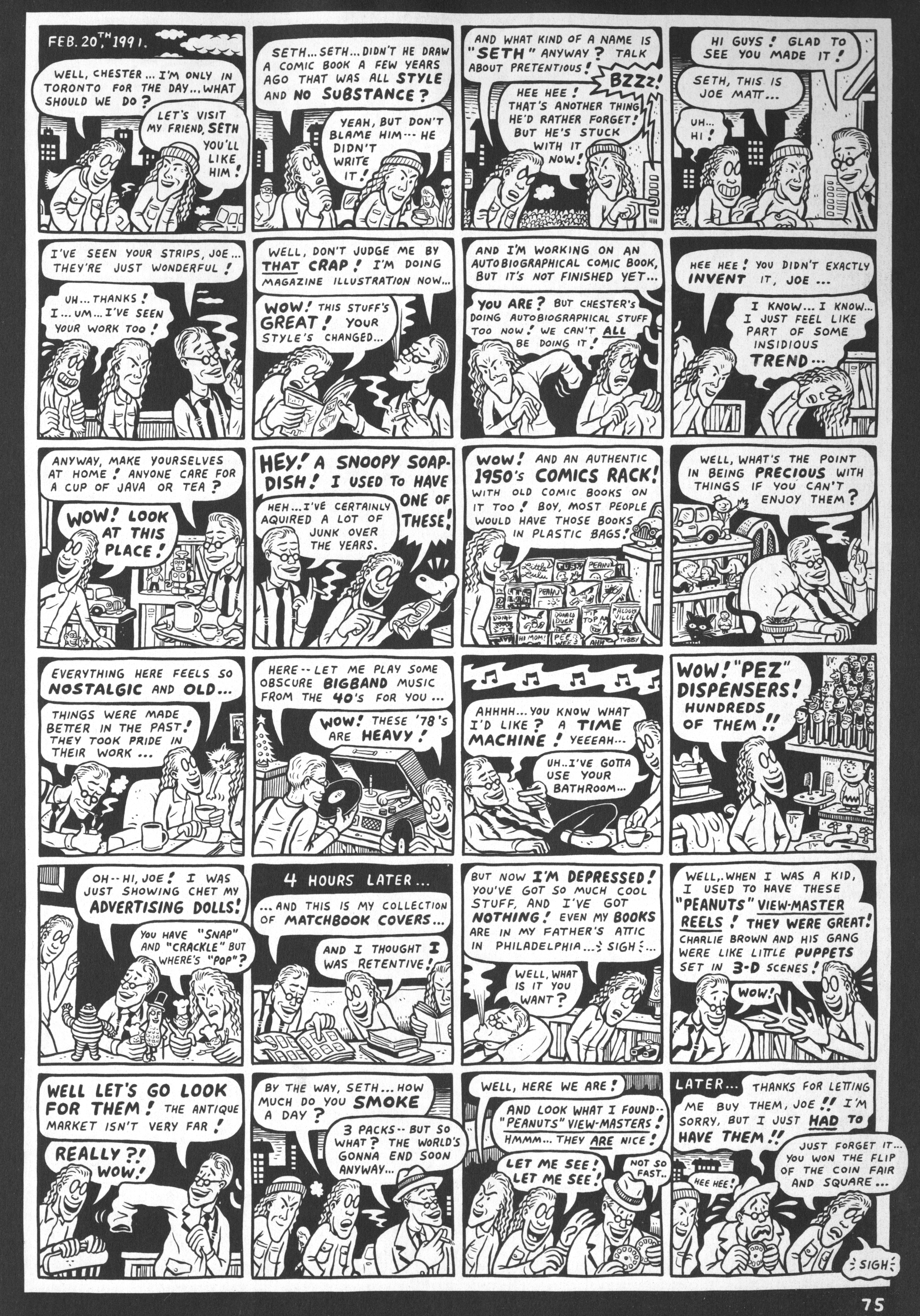

And there’s no denying that his work soon appeared alongside a rich vein of equally confessional comics by women cartoonists like Phoebe Gloeckner, Julie Doucet, Diane Noomin and Roberta Gregory. Doucet was also published by D&Q during the same period that Matt was producing Peepshow. Three male cartoonists, however, formed a triumvirate at D&Q: Matt, Chester Brown and Seth put their neuroses (Brown leaning toward prostitutes rather than porn) on display in their works, appeared together at conventions and showed up as characters in each other’s comics. Reporting on Matt’s death for The Nation, Jeet Heer wrote, “Together they formed a strange embodied realization of the Freudian trinity: Joe was the id, pure untutored carnality; Brown, a libertarian, was the ego, the cagey pursuer of rational self-interest; Seth, the melancholy romantic, was the super-ego, the one who insisted on standards of moral conduct and artistic excellence.”

All lived at that time in Canada, where D&Q was based, but Matt was not a legal resident. He was born in suburban Philadelphia on Sept. 3, 1963. His mother was a housewife and former art student. His father worked a variety of jobs before settling at Amtrak. Like Justin Green, Matt had a Catholic upbringing. After graduating from his mother’s alma mater, the Philadelphia College of Art, he went to work unloading comics at Fat Jack’s Comicrypt. His entry into the comics profession was effected by PCA classmate and Grendel creator Matt Wagner, for whom he worked as colorist and production assistant beginning in 1986. Posting on Facebook, Wagner said, “[O]ur mutual love of comics and music soon sparked a friendship that lasted through the decades.”

Matt contributed to Wagner’s 15th and final issue of Mage: The Hero Discovered and much of his Grendel series (both for Comico), as well as the Batman/Grendel crossover miniseries (1993) and the 1989 Neil Gaiman/Bernie Mireault Riddler origin in DC's Secret Origins Special #1. His coloring work was highly regarded and also appeared in the Comico Jonny Quest and Fish Police comics. This phase of his career came to an end as a result of two things: He began focusing on his life’s work, the Peepshow series, and computerized coloring became the standard for the industry, leaving coloring craftsmen like Matt behind. “I haven’t a clue how that’s done,” he told Daniel Epstein at the Suicide Girls website. “I can never color superhero comics again.”

Matt was famously averse to computers and smartphones, telling Epstein, “I don’t want a computer in my room. I don't want to have to try to control myself around these things. I don't have any self-discipline.”

Matt turned down an offer to work on a Batman cartoon series; Peepshow, pages of which began appearing in 1989 in Kitchen Sink Press’ Snarf, had already claimed his full attention. Shortly after, he moved to Montréal, where D&Q publisher Chris Oliveros invited him to contribute to the first issue of the Drawn & Quarterly anthology, which published in 1990. The first D&Q issue of Peepshow was released in 1992. Matt’s goal for the series was to proceed chronologically, reporting from the front lines of his own life. His meticulous and unhurried approach to his work, however, meant that he tended to live experiences faster than he drew them, falling behind even as the series reached 14 issues and four collected editions. After the first Peepshow collection, published initially by Kitchen Sink, The Poor Bastard continued to focus on the aftermath of his break-up with his girlfriend (who was Wagner’s sister-in-law); Fair Weather was primarily a flashback to a childhood friendship, a period he described as the happiest in his life; and the final book, Spent, seemed to work its way toward a kind of peace, with Matt’s addictions to porn and masturbation, his anxieties and sense of romantic loss, finally waning.

Peepshow spoke powerfully and generously to its readers and helped to establish D&Q’s identity as a publisher. It was a relatively strong seller for an alternative comic and brought Matt to the brink of an unaccustomed success when HBO optioned The Poor Bastard for a proposed series in 2004. The show was to be a mix of live-action and animation, in the manner of the Harvey Pekar American Splendor movie. It did not excite Matt’s modest ambitions. He told Epstein, “Writing the pilot for HBO was very stressful and I really didn't want it to move forward. I was just playing along to get that paycheck for writing the pilot. I didn't really expect or envision it going ahead…. I was never looking to switch careers from a cartoonist to anything to do with TV or film.” His hopes were granted when the cable network ultimately passed on the project.

Matt dedicated himself to capturing his interactions with life, his unapologetic compulsions and imaginings, with a kind of purity that could never have tolerated the television world’s pressure to compromise. Interviewed by Christopher Brayshaw for The Comics Journal #183 (Jan. 1996), he said, “The whole question of 'fiction' has always been troublesome to me because as a writer, you’re always drawing on your own experiences, so to try to camouflage or change things, it just seems like more trouble than it’s worth.”

One of the things that gave him considerable pleasure was drawing jam comics with other artists. When he couldn’t convince Oliveros to publish a jam comics collection, he self-published Joe Matt’s “Jam” Sketchbook in 1998. Included were collaborations with Seth, Brown, Doucet, Chris Ware, Will Eisner, Ivan Brunetti, Jason Lutes, and others. He reportedly had hundreds of jam sketches he had done with the singer Aimee Mann, who lived down the road from him in later years.

A 1990 nomination for a Harvey Award for Best New Talent was followed by nominations for Special Achievement in Humor for the next three consecutive years. Peepshow was nominated for three Eisners in 1993 and one (as collected in Fair Weather) in 2003. Matt’s coloring work on various Grendel projects was nominated for a Harvey and an Eisner in 1989, and an Eisner in 1994.

Matt’s productivity, never great, dropped off soon after the turn of the century. His last years were spent in Los Angeles, a 2003 change of venue that he was reportedly hoping to incorporate into future comics. The final abject detail that his early death invited us to speculate on was his inability to pay for medical attention that might have saved his life. For the first time, it is a detail that we won’t be able to read about in his comics.

The post Joe Matt Dies at 60 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment