Tom Strong, collected again in DC’s new "Compendium" format,1 is a clever thing. The 36-issue tome is more proof of the conceptual brilliance of Alan Moore, as if we needed it. Also: the artistic merits of penciler Chris Sprouse, as if we needed more. From the first issue to the last—by which I mean issues #1-22, and then issue #36, ignoring a stretch of fill-ins that are mostly treading water, which I’ll address separately—the whole thing is a marvel of carefully-considered structure. From the fictional setting to the timeline of events to how various elements reoccur, you can see thing whole thing has been thoroughly planned.

Launched in 1999 as part of Moore’s ABC (America’s Best Comics) line, Tom Strong appears, at first glance, to be the most traditional book on the slate. Top Ten gleefully blended superheroes with police procedural; Promethea quickly chased large metaphysical ideas into the heavens; and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen showed us how big Alan Moore’s library is.2 On the surface, Tom Strong is a rather straightforward exercise in modernized pulp. Our titular protagonist is a long-lived adventurer in the manner of Doc Savage: the peak of human physical and mental abilities. Aided by his family and supporting cast, he trots the globe (and beyond) bringing justice wherever he goes. The "long-lived" part—courtesy of extracts from a special root that allows the protagonists to live throughout the whole of the 20th century—especially helps to emphasize the pulp lineage, all the way back to Tarzan.3 But the series quickly proves more than it appears to be, with a sinister underbelly beneath the golden sheen of utopian retro-future.4

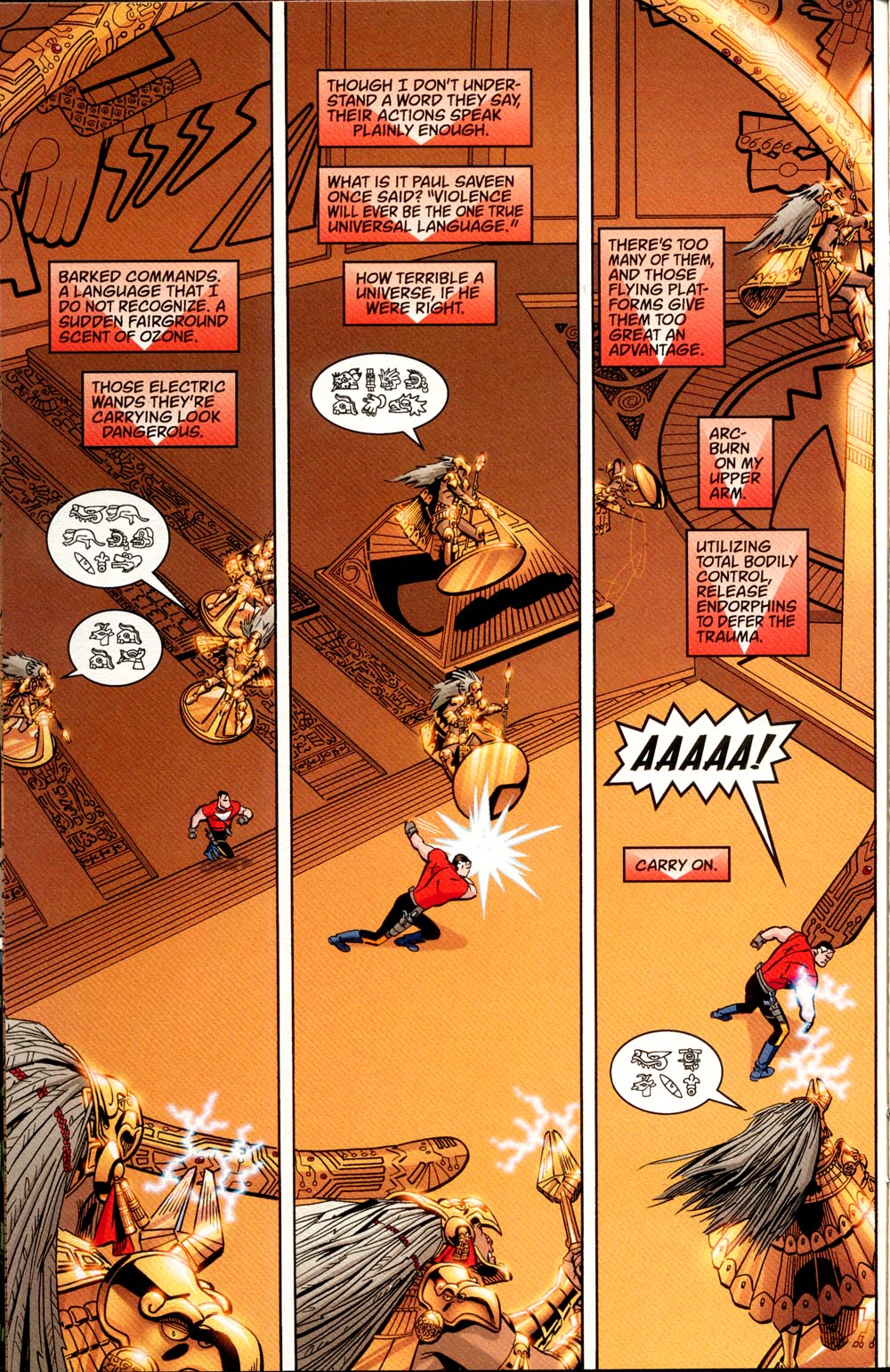

For example, in the first issue, seeding Moore’s usual metafictional interests, a young fan is told that he has been approved as member #2059 of “The Strongmen of America”; two issues later, a multi-universe spanning Aztec empire seeks to conquer Tom Strong’s own reality as the 2,058th world they'll take over. By comparison, we are given to understand that Aztecs and Americans are both variations of the same backwards-looking empire. Tom Strong’s is a gentler one, but it is still ‘his’ world. He seemingly answers to no higher authority; all government agencies are at his beck and call. When Tom's son, conceived through his rape by a villainess—again, not a very innocent world—grows up to become a Nazi, it seems less an aberration than a natural continuation. Every insult Tom throws at the fascist aesthetic can be easily returned to his own.

Is Tom not an Übermensch? Isn’t he presented, over and over again, as genetically superior thanks to his birth and strict parenting? We visit many different universes, and in almost all of them Tom's destiny is to shine. He's naturally superior. Sprouse’s art, all bold poses and broad movements, is a world people would love to inhabit: beautifully realized Gold and Silver Age kitsch married to late 20th century sheen. It is all very carefully considered. You can enjoy Tom Strong for what it appears to be, and also appreciate it for what it is.

There is only one problem. I don’t care about any of it.

I don’t regret reading the Tom Strong Compendium, because even lesser Moore is better than most other people’s best, but the whole thing feels like a big shrug. A well-executed shrug, made by Olympic champions in shrugging, but a shrug nonetheless. After 36 issues, I care for Tom Strong and his family not one iota more than I did in the first issue - which is to say, I care about them as vehicles for stories, but not in any way besides. It’s all so distant and artificial, communicated through genre exercises and knowing winks. Tom Strong, like much of the ABC line, feels like a predominantly intellectual exercise.5 Like the worst of Grant Morrison, its head is firmly screwed into its own metafictional arse.

In 1999 this was already well-trodden territory for Moore in particular, who had just concluded a run on Image's Supreme filled with stories-within-stories and art styles shifting to reflect older times; in 2023, reading metafictional and historically-aware superhero stories is almost inherently groan-inducing. The one story throughout this whole massive endeavor that actually made me feel something for the characters, that made me connect on an emotional (rather than intellectual) level to anything occurring on the page, is the short “Bad to the Bone” from Tom Strong #19, one of three short stories that issue, written by Leah Moore and penciled by Shawn McManus.

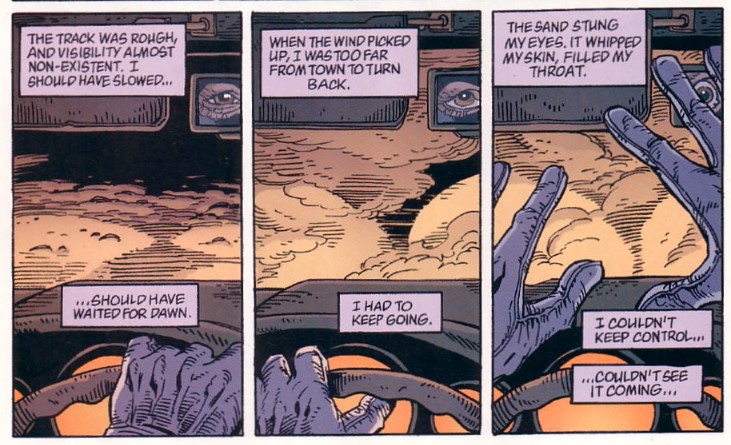

It’s an EC-esque morality play, starring Paul Saveen (Strong’s nemesis), dying slowly in the desert as he searches fruitlessly for eternal life. For longtime readers of the series this resonates because Saveen’s struggle with old age, especially compared to the long-lived Tom Strong, has been well-established. But even as a first exposure, the story works because Moore and McManus do a good job of concisely explaining Saveen’s character: he betrays the man who gives him the location of what he desires, the only man who could have saved his life, not out of malice but because after a life of betrayals it is something he does automatically, thoughtlessly. Saveen destroys himself because he is clinging to life so hard he misses anything that makes it worth living. All of this in just eight pages.

Compare this to the other guest teams, who take over the series for one or two-issue bids in the stretch between #23-35, and you’ll see a big difference. A lot of the concepts they present would probably work better in eight pages, but are spread too thin. Issue #28, by Brian K. Vaughan and Peter Snejbjerg, has a cute idea at least. We see everything from the point of view of Strong’s mechanical butler, who has been with him since boyhood, as he struggle with the final instructions left to him by Tom’s mother: “see... that he never suffers.” Because life is suffering, you see. And so, the only way to make sure Tom doesn’t suffer… well, you get the point. So did I, but the issue just keeps belaboring the same idea without adding anything. The Ed Brubaker / Duncan Fegredo arc (#29-30) fares even worse, because it’s two full issues of the old cliché of a superhero waking up in a dark and gritty reality with everyone telling him that his exciting adventures were just the stuff of comic book dreams. At 40 odd pages, this is stretched like a man on the rack - but it's the readers who get tortured.

But we can’t really talk about special guests without talking about issue #25, written by one Geoffrey Johns (and drawn by an utterly wasted John Paul Leon). These days the concept of Alan Moore approving work by the man behind Doomsday Clock seems more impossible than any alternate reality Tom Strong might visit, but there he is, just one year before Infinite Crisis would fully cement his style as the antithesis of everything Moore and Sprouse are after. Issue #25 is a Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen ‘parody’—I use that word in the broadest application allowable by the English language—which sees an annoying nerd attempting to gain Tom’s attention, leading to a serious of disastrous results via his badly explained karmic powers. A young writer muscling in on an older writer’s project to write a story about an annoying fanboy misunderstanding and ruining everything that works is the sort of things that, if it appeared as a tangential reference in Moore’s “What We Can Know about Thunderman,” would probably come off as a bit on the nose.

Intentionally or not, Johns has made a spoof not of old comics, but his own career: the faux Jimmy to Moore’s Superman. Yet Moore, in this case at least,6 has no one to blame but himself. This whole playground he has created is the exactly the kind the encourages the inwards-looking writing of Johns and his cohorts. Johns writes a bad story, yeah, but it’s not bad in a way that is unique to the other issues by non-Moore writers. The gags and reference points are more obvious, the pseudoscience more pseud than usual, but it’s a Tom Strong story. Not an aberration, but the inevitable conclusion.

The best of Alan Moore’s work is in comics, but it’s not about comics. There’s certainly an element of comics critique throughout his catalog, because he has grown and worked within the industry, and his writing reflects that fact, but From Hell isn’t a comic about comics, nor is Swamp Thing, nor is The Ballad of Halo Jones, nor is Providence - not solely. Tom Strong is the kind of work that surrenders often to cheap and immediate references: a comic about comics and its broader lineage in pulp writing. It can only see itself. The final issue, #36, is a different vantage point on the events of the final storyline in Promethea, which brought about a certain type of End of the World; I have no idea how it might have felt to readers who hadn't followed the other ABC series, which were only referenced in the most oblique manner throughout Tom Strong. But it shows the problems of Tom Strong in full. I’m far from being the world's greatest Promethea fan, but that series tried for something grand and different. It doesn’t mesh with the tone of Tom Strong at all, and the revelations it forces about the relationships between characters are straight out of the Chris Claremont playbook.

This grand sense of change, the End of the World, could work if played against Tom Strong and his family as living monoliths who never need to change. Instead, Tom and co. just accept it all without a hint of resistance. I would say this goes against the character, but there is no character, just a clothesline to hang stories on. The stories are fun, at least when Moore writes them. And they look good 90% of the time. Sprouse is properly adaptable throughout, and most of the guest artists—both assisting Sprouse throughout the Moore run and handling full issues later—are the cream of the crop of mainstream American comics of the millennial period. Tom Strong is a clever series, because Moore is always a clever writer, but the best of his work isn’t just ‘clever,’ it’s smart. A smart work goes beyond the surface, into the depths of the character and the world. It engages. It demands. Tom Strong does none of these things. Like its title character, it’s a throwback.

* * *

The post Strong Men Also Cry: The <em>Tom Strong Compendium</em> appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment