Jules Feiffer mastered every major narrative art form of the 20th century — comic strips (Feiffer), theater (Little Murders), cinema (Carnal Knowledge), novels (Harry the Rat with Women), graphic novels (Tantrum), children’s literature (Bark, George) — and he used them to capture our every neurosis, desire, fear, hypocrisy, fantasy, rationalization and twisted daydream. He was also capable of painting beautiful watercolor renditions of dancers fixed in the fluidity of a moment, but his true genius emerged when his figures were prodded into motion, dancing or walking or talking — especially talking — from panel to panel until their stories were told. His own seemingly unceasing movement was brought to an end by congestive heart failure on Jan. 17, 2025 at the age of 95.

His affinity for visual storytelling seized him at an early age. Neither athletic enough to join the neighborhood boys roughhousing and stickballing in the street nor brainy enough to earn accolades at school, Feiffer preferred to stay in his room communing with Captain Easy, Flash Gordon and Superman. “Comics: I ate them, I breathed them, I thought about them day and night.” He wrote in his 2010 autobiography Backing into Forward. “I learned to read only so I could read comics.”

Outside his room was the Depression. He had been born on its cusp on Jan. 26, 1929 in the Bronx. Like much of the population in that era, his father David, a World War I hero, had failed at business and was mostly unemployed. His mother, Rhoda, brought in the family’s meager income by selling clothing designs — sketches at $3 apiece — to New York area fashion houses. Comics allowed Feiffer, a middle child between two sisters, a four-color refuge from reality, but he didn’t escape unscathed. He described his father as cowed by financial failure and his mother as embittered by the burdens she’d been forced to shoulder. As he recounted in his autobiography, he was his mother’s greatest hope and her perpetual disappointment. This resulted in a permanently strained mother-son relationship.

Still, it seems likely that Rhoda Feiffer inspired, directly or indirectly, much of the creative course of his life. For one thing, her dissatisfactions fueled his own ambitions and set the stage for years of psychotherapy, which instilled in him an appreciation of the unconscious motivations of urban Americans. Though he never graduated from college (a fact that fed a lingering inferiority complex), his sensitivity to modern neuroses aligned him with a milieu in which writers and artists were enthusiastically exploring the ramifications of Freudian theory. And even if his mother can’t take credit for single-handedly driving him into the arms of psychotherapy, she was, after all, the artist of the family. Her hours huddled over the table drawing were a glimpse into his own future.

Feiffer rarely spoke of his mother as an influence on his artistic career, but it’s hard not to notice that his comics were entirely centered on the human figure, just as his mother’s fashion sketches had been. Her figures were often in the act of walking, but there was no other panel for them to walk into. They progressed from dress to dress, always ready to go out, but hung motionless in space. Her son’s figures changed emotions and rationales the way hers changed clothes, and, most of all, following the example of his beloved comics, they broke free from his mother’s single-panel cage, moving from panel to panel in a cumulative sequence of actions, arguments, emotions, thoughts and conflicts.

Already, at the age of 7, as evidenced by the sketches he drew of Popeye and other comics heroes, he had a style. His bodies were in motion, had weight and momentum. He was 7 when he won a gold medal in the John Wanamaker Art Contest for his crayon rendition of cowboy star Tom Mix capturing an outlaw. Pre-Superman, other kids Feiffer’s age were mostly following radio serials, while Feiffer was “counting how many frames there were to a page, how many pages there were to a story — learning how to form, for my own use, phrases like: @X#?/; marking for future reference which comic book hero was swiped from which radio hero” (Feiffer’s The Great Comic Book Heroes, 1965).

His skills were not enough to impress Will Eisner when Feiffer, at the age of 16, applied for a job with the creator of The Spirit. As Feiffer recalled in Backing into Forward, Eisner looked at the boy’s work and told him it “stank.” When it became clear that Feiffer knew Eisner’s comics inside and out, however, Eisner hired him to work half-days as his assistant, erasing and cleaning up art — for no pay.

Feiffer’s art lacked the hard edges necessary to draw things like guns and cars — staples of the urban crime and superhero comics he admired. What he did have was a strong grasp of storytelling, an area where Feiffer felt Eisner was beginning to slip. As revolutionary as the Spirit strip was, Feiffer believed that Eisner, always a shrewd businessman, had become distracted by other ambitions for non-comics magazines devoted to things like baseball and fishing. When Feiffer criticized Eisner’s scripts, Eisner told him to try writing a Spirit script himself. Feiffer gave it a shot, channeling early Eisner mixed with his favorite hard-boiled radio shows — and Eisner liked it. In Michael Schumacher’s biography Will Eisner: A Dreamer’s Life in Comics (2010), Eisner described Feiffer as having “an ear for writing characters that lived and breathed.”

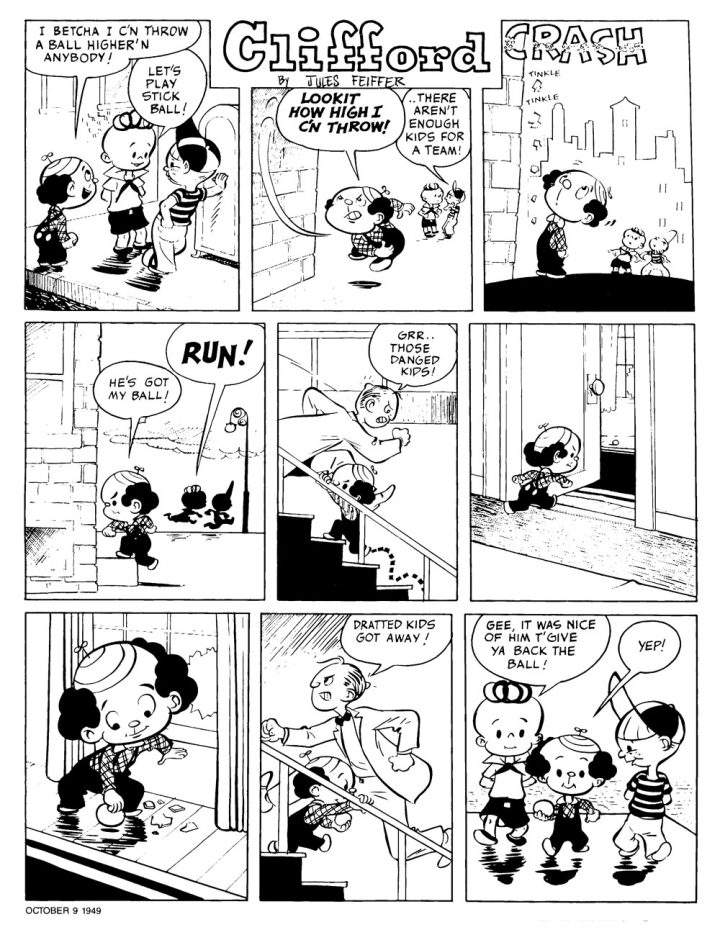

Feiffer’s nonexistent salary was raised to $10 (later $20) a week and he found himself, at the age of 17, working on The Spirit alongside Eisner studio-mates Jack Cole and Wally Wood. Eisner even allowed Feiffer to do his own strip at the back of the Spirit section (which Eisner treated as a form of compensation, taking the place of, rather than earning, higher pay). In contrast to The Spirit’s adventure stories, Clifford was a cartoonish humor strip presenting the world through the eyes of its bubble-headed kid protagonist.

Eisner and Feiffer, who shared Bronx childhoods, families that struggled with poverty and strong mothers, became increasingly close collaborators, with Eisner often providing the opening page of a Spirit strip and Feiffer scripting the rest. Feiffer made a couple of brief forays into higher education at the Art Students League and the Pratt Institute, but most of what he learned came from the cartooning trenches of Eisner’s studio. In 1949, however, the draft was looming over the 20-year-old Feiffer. His girlfriend, in a display of courage and independence that amazed him, had hitchhiked to California to attend UC – Berkeley, and Feiffer decided to surprise her with the grand romantic gesture of following in her ride-thumbing footsteps on the eve of being sucked into the Korean war. In his autobiography, Feiffer described this quest, his first trip so far from home (with stopovers to try to sell his mother’s designs), as a maturing experience, not least because at the end of it, his girlfriend snubbed him.

The Army was not so choosey, and in 1951, he found himself suffering through basic training at Fort Dix, New Jersey. After a frustrating stint failing to learn how to repair radios in Fort Gordon, Georgia, he ended up at a desk in the Signal Corps Publications Agency in Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, where he worked on training manuals, maps and other projects.

Encyclopedia Britannica reports that Feiffer “did cartoon animation” while in the Army and Encyclopedia.com says he worked in a “cartoon-animation unit,” but none of Feiffer’s own accounts of the period give credence to that. What he did do while sitting at his desk was dream up “Munroe” (later Munro). Inspired by his own experiences in the bureaucratic maze of the armed services, it was a cartoon tale of a 4-year-old boy accidentally drafted into a military that refused to recognize that he didn’t belong there. “Munro was going to be a subversive book,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Before I knew much else about it, I knew that. It was going to attack the mindset of the military in a time of war. It was going to do so not as a polemic or a scathing satire but as a funny and entertaining story. A children’s story. For adults.”

Drawing from the influence of various cartoonists and his interactions with the three GIs who worked alongside him at the Publications Agency, Feiffer created a fable that was both cartoonishly charming and an existential, Kafkaesque indictment of bureaucratic blindness. Ten years later, Munro would become an Oscar-winning animated short directed by Gene Deitch. “Munro and my early struggles to learn how to do what I do, figuring out what story to tell and how to tell it, discovering that just when you think you’ve reached a peak, that’s when you go for more, raise the ante,” he wrote. “And just when you think you’ve about come to the end, that you’re almost finished: Slow down, not so fast. All these facets of writing, whether for cartoons, theater, film, or children’s books, I began to figure out at my desk at the Signal Corps Publications Agency.”

After serving for two years in the Army, Feiffer was honorably discharged into another kind of limbo working half-heartedly at spot illustrations for small art studios. With Munro, he had found his blackly humorous cartoon storytelling voice and streamlined style, but there was no place to publish something like Munro, no audience, no venue. To do the kind of work he wanted to do, he had to wait for that audience and venue to be invented — which happened in 1955 with the founding of The Village Voice. It was a new kind of alternative newspaper, reflecting the beginnings of a countercultural perspective that could only have been born in Greenwich Village. His cartoons began appearing in the Voice in 1956, captivating readers with mini-narratives of sexual politics, social politics and political politics, and earning him — no pay.The trade-off was that Voice editors never told you what to do, or what you couldn’t do, for no pay. Feiffer was free to draw the kinds of cartoon strips he envisioned without interference. And because he had seen copies of the Voice on the coffee tables of the publishers that had rejected him, he knew his work would be seen by other cartoon editors. And it was seen, gradually becoming a new standard for cartooning.

Quoted in a 2014 Washington Post article, This Modern World cartoonist Dan Perkins (Tom Tomorrow) said, “Jules Feiffer is the man who invented the genre we now call ‘alt-weekly cartooning,’ and everyone who came after him owes him an immense unpayable debt of gratitude. Without Jules, there would probably have been no Matt Groening or Lynda Barry, and there certainly would not have been a Tom Tomorrow.”

Feiffer’s strips at the Voice became not only a regular feature — called Sick, Sick, Sick, and then simply Feiffer — but one of the things the Voice was known for. Feiffer was able to collect and package the strips into profitable books, but he drew no pay at all from the Voice until the mid 1960s. Despite this uncompensated labor, it was a mutually beneficial, long-lasting relationship, as both the Voice and Feiffer rose in profile. From his first Voice strips until his cancellation in 1996 as new owners slashed the paper’s comics, Feiffer distilled the absurd essence of seven presidential administrations, including Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Carter and Reagan. Politically, Feiffer was a classic left-wing cynic, but psychologically astute enough to understand both the xenophobic nightmares that drove right-wing bullying and the self-doubts that gnawed away at white, liberal motivations.

Feiffer was nothing if not observant and what he observed happening in the country undermined his idealistic streak early on. He was severely disillusioned when writer Clifford Odets, after strongly condemning the government’s anti-Communist witch hunt, ended up naming names before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Feiffer had heard Odets deliver a fiery, inspiring speech at the funeral of a blacklisted screenwriter (an experience that found its way into more than one of Feiffer’s works) and he was present when Broadway choreographer Jerome Robbins caved in to pressure and cooperated with HUAC. “Odets educated me,” Feiffer wrote, in Backing into Forward. “He taught me there were no heroes, there was no one to trust.”

Feiffer perceived that the flame had gone out beneath the melting pot that had absorbed his own parents, and as a result, the disparate elements of American society had begun to congeal. Speaking to the American Civil Liberties Union during Ronald Reagan’s first term as president, Feiffer painted a starkly clear-eyed picture of the multiple Americas that have solidified around us more and more firmly in the ensuing decades: “With the death of ‘the American Dream,’ we have become woefully aware that there is not one America out there but 200 or 300 Americas, closet Americas, whose citizens owe a stronger allegiance to their own codes, their own systems of values, their own closet constitutions than they do to the Constitution of the United States; led to believe in the cultural and political correctness of their particular America over all other Americas, schooled first and foremost in the rules and regulations, the laws of their closet America.”

The Voice was a defining venue for Feiffer, allowing him the space to develop his style of expression and political point of view, a place where he could put Americans on the couch and probe their psyches, and a spotlight that introduced him to the cool, comedic intelligentsia of the 1950s. Having made a name for himself, he was invited to all the right parties and got to know people like Mort Sahl, Mike Nichols, Elaine May, Terry Southern, Joseph Heller, Phillip Roth, George Plympton, Peter Matthiessen, Nelson Aldrich, Alexander King, Al Hirschfeld, William Styron, Lillian Hellman, Bruce Jay Friedman and Hugh Hefner.

What he hadn’t made for himself was a steady income. Luckily, one of his creative acquaintances was Gene Deitch. Deitch, like everyone else, had seen Feiffer’s work in the Voice and invited him to join the crew of artists and animators Deitch was putting together at Terrytoons. This gave Feiffer a much-needed financial boost, but it proved to be short-lived. His first assignment at Terrytoons, which was best known for Mighty Mouse, was to design a series of low-budget animated shorts to replace the long-running Tom Terrific series on Captain Kangaroo. Feiffer’s pitch for Easy Winners, a series of minimalist, three-minute allegories involving a cast of amiable street kids, was deemed too intellectual by CBS execs, and his stay at Terrytoons ended shortly afterward. Deitch and Feiffer, however, made their mark on animation history when Deitch’s 1960 animated adaptation of Munro, the cartoon story Feiffer had conceived while in the Army, won an academy award for Best Animated Short Film at the 1961 Oscars.

Showcases for his cartooning were increasing. “Passionella,” a narrative cartoon satire of Hollywood celebrity culture, ran in Pageant in 1957 and was redrawn by Feiffer in graphic-novella form two years later. Passionella and Other Stories, published in 1959, included the Munro story that Deitch had adapted. Hefner saw “Passionella”’s appearance in Pageant, as well as the Sick, Sick, Sick collection of Feiffer’s Voice work, and offered him a regular cartooning gig for the publisher’s fledgling Playboy magazine in 1958. As Feiffer’s visibility widened, opportunities to sell out multiplied. In 1959, he wrote and drew some clever ads for Rose’s Lime Juice, but overcome with shame, he pulled out of the account and never did another ad. Ironically, the lime-juice ads were the first appearances of his work in The New Yorker.

The early 1960s marked Feiffer’s first work on a children’s book and the birth of his first child. At a party thrown by theater critic and producer Kenneth Tynan in 1960, Feiffer met Judy Sheftel, a photographer and confidante of poet and activist Maya Angelou. After living together for three years, Feiffer and Sheftel, who became a novelist and editor, were married in 1963, and a year later, their daughter Kate was born. In 1961, he illustrated the much-loved The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster, who had been Feiffer’s roommate while writing the book.

In 1963, Feiffer published his first novel, Harry the Rat with Women, a kind of male version of “Passionella,” with its coddled protagonist shaped more by the expectations of those around him than by an inner life. Accustomed to the distilled purity of his strips, Feiffer struggled painfully with this long-form fiction. It was a success, with both the hardcover and a two-part Playboy serialization bringing in a welcome influx of cash, as well as offers of movie and Broadway adaptations (including a proposed musical by Little Shop of Horrors composer Alan Menken). But Feiffer turned all the adaptations down and would not be coaxed into writing another novel until 1977’s Ackroyd.

Theater came more naturally, but not without the occasional crisis of confidence. Feiffer’s writing first appeared onstage in Chicago in 1961 when the Second City comedy troupe adapted a collection of his Voice strips under the title The Explainers. The performance was seen by Mike Nichols, then a comedian on his way to becoming a theater director and eventually a film director. Nichols proposed to adapt some of Feiffer’s cartoons and monologues, including a musical version of “Passionella” with songs by composer Stephen Sondheim. After New Jersey tryout performances of The World of Jules Feiffer, however, Feiffer got cold feet about bringing the production to New York, and the project was abandoned. “And the rest,” as Feiffer wrote in Backing into Forward, “is not history.”

“Crawling Arnold,” however, was a one-act play — in which an adult inhabits the life of a child, a kind of inversion of “Munro” — written by Feiffer for the stage rather than the page. It was performed in 1962 along with several adaptations of Feiffer cartoons by Harvard’s Poet’s Theatre, but it was “Arnold” that stood out for critic Fred Gardiner of The Harvard Crimson. He wrote, “An uproarious, perceptive play about a man of 35 who finds genuinely childish behavior the logical response to a hypocritical, senile world, Crawling Arnold invalidates the praise Feiffer once received — ‘your people speak just like real people; put them on the stage and they'll sound just like real people.’ His cartoons and his theater share not the tape-recorded quality of real life, but the synoptic terseness of drama. His dialogue is not literal chatter, it is a precis of real conversation that takes into account the encumbrances of colloquial speech. And while real people can lie successfully, Feiffer's only exist to reveal some truth.”

Feiffer’s breakthrough play was Little Murders, but it tanked when first staged in New York in 1967, closing four days after it opened. Even Nichols was initially unresponsive to it, which caused Feiffer to stop speaking to him for more than a year. But two months after it had closed in New York, it reopened in London, the first American play staged by the Royal Shakespeare Company, and became an award-winning success. This English validation caused New York to see the play in a new light. A new production was directed by Alan Arkin for the Village theater Circle in the Square in 1969 and this time it was a hit, the biggest financial success of Feiffer’s theater career, which went on to include Jules Feiffer’s People (1969), “Dick and Jane” (his one-act contribution to the 1969 production of Tynan’s erotic revue, Oh Calcutta!), The White House Murder Case (1970), Knock Knock (1976), Grown Ups (1981), Elliott Loves (1990) and A Bad Friend (2003). The flop-turned-hit had yet another life as a 1971 film also directed by Arkin and starring Elliott Gould, who had also played the lead role on stage.

Feiffer’s breakthrough play was Little Murders, but it tanked when first staged in New York in 1967, closing four days after it opened. Even Nichols was initially unresponsive to it, which caused Feiffer to stop speaking to him for more than a year. But two months after it had closed in New York, it reopened in London, the first American play staged by the Royal Shakespeare Company, and became an award-winning success. This English validation caused New York to see the play in a new light. A new production was directed by Alan Arkin for the Village theater Circle in the Square in 1969 and this time it was a hit, the biggest financial success of Feiffer’s theater career, which went on to include Jules Feiffer’s People (1969), “Dick and Jane” (his one-act contribution to the 1969 production of Tynan’s erotic revue, Oh Calcutta!), The White House Murder Case (1970), Knock Knock (1976), Grown Ups (1981), Elliott Loves (1990) and A Bad Friend (2003). The flop-turned-hit had yet another life as a 1971 film also directed by Arkin and starring Elliott Gould, who had also played the lead role on stage.

Little Murders begins small — the stage version opens on a family living room — observantly lampooning family dynamics and relationships between men and women Feiffer-style, but about two-thirds in, it takes a mercilessly sharp turn into pitch-black political commentary as the world outside the family and the couple violently intrudes. Just when you think the characters are headed for an ironically happy ending, the curtain is jerked aside to reveal Americans as their own worst enemy. Of the film version, critic Roger Ebert wrote, “It left me with a cold knot in my stomach, a vague fear that something was gaining on me.” One could hardly guess he was describing a comedy.

The year of Little Murders’ conception was the year riots broke out at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, and Feiffer came face to face with political reality in a way that literally shattered his privileged authorial viewpoint. In his autobiography, Feiffer described drinking martinis with writer Studs Terkel and other colleagues in the Hilton Hotel bar while police battered protesters on the other side of the bar’s plate-glass picture window — until the glass failed to hold and the brutal spectacle spilled into the bar. Feiffer was so shocked by the experience that he returned to the Playboy Mansion, where he was staying, and insisted that his host, Hefner, accompany him into the streets to see what was happening firsthand. A small expedition, including Hefner, columnist Art Buchwald and historian Max Lerner, left the Mansion on foot, and Hef soon found himself shoved against a wall by a Chicago policeman and struck by a nightstick. Feiffer proudly credited himself with the subsequent radicalizing of Playboy’s editorial stance.

Feiffer was a Eugene McCarthy delegate to the convention, but his role began to feel irrelevant after witnessing the thuggish response of Mayor Daly’s police to protesters. In a 2011 Comics Journal interview, he told Gary Groth, “To me, the real action was going on in the streets, and what the police were doing in the streets of Chicago to these kids who were protesting. The violence and the police riot that we know fully about now was quite clear back then, and it was not being dealt with on the floor in any way, so I just resigned on some kind of radio interview, and that caught no one’s attention but my own.” In 1971, Grove Press published Feiffer’s Pictures at a Prosecution: Drawings & Text from the Chicago Conspiracy Trial.

The same year that the movie of Little Murders was released, Feiffer’s marriage to Sheftel came to an end and Feiffer’s Carnal Knowledge, directed for the screen by Nichols, shocked Hollywood and drew rave reviews for its evisceration of male-female relationships. Feiffer’s script was unflinching in its examination of American sexual mores, giving audiences ringside seats for harrowingly intimate confrontations between Jack Nicholson and Ann-Margret, as well as mainstream cinema’s first onscreen blowjob. After showing the film, a theater owner was convicted of obscenity by the Georgia Supreme Court, but the verdict was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1974. Feiffer had intended the dialogue-driven Carnal Knowledge as a play until Nichols proposed to do it as a film, and it was revived as a play in 1988 in Houston and two years after that Off-Broadway.

It may seem that Feiffer’s movie scripts, with their long speeches and dialogue passages, were like plays, but it would be more accurate to say that both his plays and his films were like his strips. It could also be said that his strips were like mini-plays, which is why theater people and sketch-comedy groups kept wanting to adapt his strips into revues for the stage. But the episodically punctuated pacing of his scenarios originated nowhere but in the comic strips — the three-panel gags and adventure continuities that had impressed themselves on his young mind. As with his Voice cartoons, his scenes took as long as they liked to build to a pay-off, but, like a Captain Easy strip, they were always as discretely autonomous as they were part of a larger whole. As dark as Carnal Knowledge or Little Murders are, each scene builds to a gag or an irony. The Nicholson/Art Garfunkel pair in Carnal Knowledge might as well have been Feiffer’s Voice strip semi-regulars Bernard and Huey, avatars of dysfunctional masculine self-regard. In fact, the neurotic, self-reproaching, angst-ridden Bernard and the confident, successfully repressed Huey were the protagonists of Feiffer’s 2017 indy film Bernard and Huey. Based on a 1986 script, lost for decades, the film reunited the characters, while tracing their shifting balance of power.

The stature of Carnal Knowledge has only grown over the years, but at the time, the Hollywood establishment averted its eyes, ignoring Nichols and Feiffer at the Academy Awards (though Ann-Margret won for what was by far the most impressive performance of her career). Only two other Feiffer screenplays made it before the camera during his lifetime, though there were many close calls, unproduced scripts and rejected job offers. For a time, Feiffer’s most lucrative activity was collecting cash for screenplays that he knew would never reach the screen. As Feiffer told Screen Slate’s Tyler Maxin in a 2019 interview, “They love the idea of me, but they hate the fact of me. When I did this work for other people, they thought it was terrific, when I did it for them, they didn't want to touch it.”

Stanley Kubrick (like Feiffer, born in the Bronx) twice approached him — to do a film based on Feiffer’s recurring dancer from the Voice strips and to write what became Terry Southern’s script for Dr. Strangelove. Despite his admiration for Kubrick, Feiffer balked at both, perceiving that the resulting films would be Kubrick’s visions rather than his own. A version of Little Murders was nearly directed by the legendary Jean-Luc Godard, but he and Feiffer failed to see eye to eye. Alain Resnais, like Godard, part of the Mount Rushmore of French New Wave directors and, incidentally, a comics fan, had no such problem with Feiffer. Their 1989 collaboration, I Want to Go Home, about an American cartoonist in Paris, won a Best Screenplay Award at the Venice Film Festival, but went undistributed in the U.S. It wasn’t until the DVD release 20 years later that it found an appreciative English-language audience.

Feiffer’s only other realized film was 1980’s Popeye, which ran out of money toward the end of filming and has a reputation as a flop, but it was in fact successful everywhere but the U.S., its box-office take more than doubling its budget. Life magazine sent 25-year-old reporter Jennifer Allen to Martha’s Vineyard to interview Feiffer about Popeye. He asked Allen to dinner, and, after the article was published, she accepted. Three years later, she became his second wife, ending a 12-year bachelor stretch for Feiffer, though he had been in a six-year relationship with painter Susan Crile.

Popeye was directed by Robert Altman and starred Robin Williams, both well known for ignoring scripts in favor of improvisation. Feiffer admired Altman, but told Groth in the TCJ interview, “My struggle with him was to keep his film in the background while my film and Segar’s was in the forefront. And sometimes I won at that, and sometimes I lost. I figured I didn’t do too badly, because about 60% of what I wrote got on the screen, but I think that if the other 40% got on it would have been better. As it was, I don’t think the film turned out badly.”

The film was shepherded by producer Robert Evans, though most Hollywood suits would have been terrified of Feiffer’s vision for this big-budget children’s musical. “There was something Kafkaesque in that world, and there was something Beckett-like in that world,” he told Groth. Audiences familiar with Popeye only through reruns of the Fleischer Studios cartoons may have been surprised to encounter Feiffer’s psychoanalytic take on the eccentrically intricate narratives and characters of Elzie Segar’s original comic strip, but, internationally, kids seemed to respond to the film’s internal logic and surreal absurdity. For Feiffer, the pay-off was a phone conversation with Segar’s daughter just after she had seen the film. “She was in tears,” he told Groth. “She said it was everything she had hoped it would be. That it was his Popeye, she was just bowled over by it. She was crying and I was crying. It was wonderful. It was just wonderful. So that made a lot of it worthwhile.”

Whatever form Feiffer was working in, comics — their sequential rhythms and juxtaposings — were at the base. In 1965, he paid a debt to the comic books he had grown up with by writing what may be the best book about comics ever published: The Great Comic Book Heroes. Half the book was given to reprints of classic Golden Age superhero origin stories, but the other half was a history of comics creators and superhero genre tropes filtered through his self-aware, witty, psychologically astute memories of those comic books. No other history of comics has been as entertainingly analytical and as steeped in the arcane joys of comics reading.

As seen in Munro and Arnold and virtually every character Feiffer has written, he was always conscious of the child in the adult and the adult in the child. When he wrote books for children (not to mention his Popeye screenplay), he never wrote down to them. The first book written and drawn by Feiffer for children was The Man in the Ceiling (1993), an autobiographical fiction about a boy who is fascinated with comic books and drawing and whose relationship with other kids has all the alienating and bonding complications of an artist and his or her audience. Though intended for 8-to-12-year-olds, it was sophisticated enough in its insights to be produced as a musical in 2017, directed by Hamilton producer Jeffrey Seller with compositions by Andrew Lippa (who wrote the songs for the musical version of The Addams Family, another cartoon-based stage show).

His work on children’s books continued steadily through the 1990s and early 2000s. Publishers Weekly described A Barrel of Laughs, a Vale of Tears (1995) as “sophisticatedly silly.” Meanwhile … (1997) was about a boy who utilizes the narration box from a comic book to transition himself to new locations and situations. Bark, George (1999) is a favorite of kids, with its simple story of a dog who, instead of barking, makes the sounds of various creatures he has swallowed. A vet coaxes the animals out of George’s mouth one by one, each impossibly larger than the last until the sequence reaches a gag that tickles adults as well as kids. Other children’s books by Feiffer include I Lost My Bear (1998), I’m Not Bobby (2001), By the Side of the Road (2002), The House Across the Street (2002) and The Daddy Mountain (2004). His daughter Kate has written several popular children’s books, often with illustrations by her dad. Those collaborations include Henry the Dog with No Tail (2007), Which Puppy? (2009), My Side of the Car (2011) and No Go Sleep (2012).

But always, he returned to his first love: comics. His cartoons could be found in Saturday Evening Post, Playboy, The Nation, The New Yorker, Esquire, Life, Mademoiselle, Ramparts, Holiday and Commentary. And paid or not paid, he produced a stream of cartoons for The Village Voice and that became the well from which he drew collections of cartoons that were published every couple of years for the rest of the 20th century. His first book of cartoons was Sick, Sick, Sick in 1958. It did so well that a second edition was published in 1959 with an introduction by Kenneth Tynan. A partial list of Feiffer’s books of cartoons includes: Boy, Girl, Boy, Girl (1961), Feiffer’s Album (1963), The Unexpurgated Memoir of Bernard Mergendeiler (1965), Feiffer on Civil Rights (published by the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai Brith in 1966), The Penguin Feiffer (published in England in 1966), Feiffer on Nixon: The Cartoon Presidency (1974), Feiffery: Jules Feiffer's America from Eisenhower to Reagan (1982), Marriage Is an Invasion of Privacy, and Other Dangerous Views (1984), Feiffer’s Children (1986) and Ronald Reagan in Movie America (1988). Four volumes of his collected works were published by Fantagraphics between 1989 and 1997. His Voice strip was syndicated outside New York by the Robert Hall Syndicate and Universal Press. When his run at the Voice finally ended in 1997, Feiffer immediately transitioned to The New York Times, where he drew the notoriously comics-free newspaper’s first Op Ed comic-strip, a regular feature until 2000.

He was a cartoonist who captured the admiration of more than one generation of cartoonists. On the occasion of Feiffer’s 89th birthday, Doonesbury creator Garry Trudeau told The Washington Post that Feiffer was a “huge influence.” In the same Post article, Understanding Comics author Scott McCloud said, “I’m struck by his youthful exuberance for the form, awareness of contemporary trends, and his good-hearted appreciation of previous generations. A resilient, adaptable mind, but with unshakeable convictions. It’s a nice combination.”

It is exhausting just to try to list all the awards Feiffer won over the course of his multiple careers. He received a Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning in 1986. Twenty-six years later, he was still getting awards for editorial cartooning, this time the 2012 John Fischetti Lifetime Achievement Award from Chicago’s Columbia College. In 2003, the National Cartoonists Society presented him with the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award. At the 2010 Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards, named after his mentor, he was inducted into the Comic Book Hall of Fame. As noted, he received an Oscar for “Munro” in 1961 and a Best Screenplay Award for I Want to Go Home at the 1989 Venice Film Festival. In 1961, he was the recipient of a Special George Polk Memorial Award, an honor generally handed out to journalists. Little Murders, the play, collected a Best Promising Playwright Award from New York Drama Critics, a Best Foreign Play of the Year from London Theatre Critics and an Outer Critics Circle Award and Obie Award from The Village Voice. In 1970, The White House Murder Case also received an Outer Critics Circle Award. Bark, George was given a Red Colver Children’s Choice Picture Book Award in 2000. In 2004, the Writers Guild of America presented him with the Ian McLellan Hunter Award for Lifetime Achievement in Writing. Also in 2004, he received the Chicago-based Harold Washington Literary Award and the Patricia A. Barr Shalom Award from Americans for Peace Now. Although he never graduated with a college degree, he was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters by Long Island University in 1999 and was elected to the Academy of Arts and Letters in 1995. He taught at numerous colleges and universities, including the Yale School of Drama, Northwestern University, Dartmouth College, the American Academy in Berlin and Southampton College, where he occupied an ongoing adjunct faculty position from 1998 on.

If anybody ever had a comfortable bed of laurels to rest on in retirement, therefore, it was Jules Feiffer as he approached his 83rd birthday in 2012. Instead of retiring, however, he excitedly announced that he’d found a new drawing style and planned to apply it to not just a graphic novel but a trilogy of graphic novels. And then he proceeded to do so, turning out Kill My Mother in 2014, Cousin Joseph in 2016, and, at the age of 87, The Ghost Strip in 2018. He paused in this output in 2016 just long enough to embark on a new marriage, his third, to JZ Holden (then 68) playwright and author of the 2013 epistolary Holocaust novel Illusion of Memory). His marriage to Allen had ended in 2013 after 20 years and two daughters.

Kill My Mother was technically not his first shot at a graphic novel. That would be Tantrum, a 1979 variation on the regressed-adult theme of “Crawling Arnold” in comics form that was one of the first shots by anyone at a graphic novel. In an introduction to the 1997 Fantagraphics edition of Tantrum, writer Neil Gaiman wrote, “When the history of the Graphic Novel (or whatever they wind up calling long stories created in words and pictures for adults, in the time when the histories are appropriate) is written, there will be a whole chapter about Tantrum, one of the first and still one of the wisest and sharpest things created in this strange publishing category, and one of the books that, along with Will Eisner's A Contract With God, began the movement that brought us such works as Maus, as Love and Rockets, as From Hell — the works that stretch the envelope of what words and pictures were capable of, and could not have been anything but what they were, pictures and words adding up to something that could not have been a film or a novel or a play: that were intrinsically comics, with all a comic’s strengths.”

Tantrum, then, was a demonstration of what long-form comics could do, but not entirely a departure for Feiffer. It was an extended cartoon exploration of an idea in the vein of “Munro” or “Passionella” — but as groundbreaking as it was, it was not particularly novelistic. When Feiffer returned to the form 35 years later with Kill My Mother, he produced a work that was in every sense of the term a graphic novel.

For the first 70 years of his career, Feiffer’s cartooning had been driven by a gag or a point that was always just around the corner. If it wasn’t one person holding forth, it was generally a pair of characters passing an idea back and forth like a football until the play was complete a few minutes or panels later. As he embarked on Kill My Mother, he began construction of a fully realized fictional environment crisscrossed with intricate narrative threads and populated by enough psychologically complex characters to fill a Russian novel. In his screenplay for Popeye, the large cast of characters had fully inhabited Segar’s world (Sweethaven, the movie called it), but the trilogy was a first for Feiffer: a world of his own, inflected with all his historical, psychological and aesthetic obsessions. The story beats and atmosphere are fashioned out of pulpish noir elements ranging from Raymond Chandler to Sunset Boulevard, but the trilogy is also a multi-generational family mystery that winds through the American century touching on the Depression, the House Un-American Activities Committee, WWII in the Pacific, cross-dressing, a USO tour, radio days, Hollywood, urban corruption, political conspiracies and jitterbugging teenagers. Each part of the trilogy has a story to tell, with Cousin Joseph’s prequel revealing events that set the stage for Kill My Mother, but the proliferating ironies don’t become entirely clear until The Ghost Script, which brings together ghosts of the past, government spooks and imaginary phantoms of the silver screen.

Another ghost whose stylistic imagination influenced the trilogy was Feiffer’s old boss. “I’m working on a page and I think Eisner would do it this way,” he told Charity Robey in a 2017 Shelter Island Reporter interview. “He’s standing on my shoulder as I’m doing these pages, more so now than in the 40 years when I was doing the Voice strip.” He even found a way to suggestively render guns and cars. There is a sense of dashed-off spontaneity to the art, but it never abandons the job of storytelling. Expressive and immediate in their conveyance of narrative, scenes hurtle forward in the trilogy, despite generous sprinklings of Feiffer dialogue, sometimes adopting a style that is more cinematic choreography than literal, detailed illustration. Reviewing Kill My Mother in The New York Times, Laura Lippman wrote, “His kinetic line drawings unspool like an obscure film found during late-night channel surfing.”

This effect was intentional, as Feiffer told Screen Slate in 2019: “I approached them from the script to the layouts as movies on paper and in which I played every role. I was all the actors and cast all the actors. Not only was I the screenwriter, but I was the director who threw out the script of the screenwriter and rewrote lines as I was doing the finished page. More and more as I did the trilogy, it became more cinematic to me and more movies on paper.”

The down side of this style was that more than one reader found it difficult to keep track of the large cast of sometimes cross-dressing characters, especially with the trilogy’s jumps forward and backward in time — a problem that the 10-year-old Feiffer might have solved with judicious use of an old, non-cinematic, comic-book device, the narration box.

Even so, the trilogy was a critically praised best seller, with Kill My Mother chosen as one of the best books of the year by both Vanity Fair and Kirkus Reviews. Tegan O’Neil of The Onion’s AV Club wrote, “This is someone who by all rights should be living a peaceful retirement crashing the party and straight-up embarrassing cartoonists one-quarter his age. Kill Your Mother is a wonder of a book that, rather than using its author’s reputation as cover for its deficiencies, dares the reader to imagine another book this year, by any other cartoonist, feeling quite so vibrant and daring.”

As soon as the trilogy was completed, Feiffer launched a new comic-strip series called Feiffer’s American Follies, which began appearing monthly in Tablet Magazine in 2018. It was a continuation of Feiffer’s regular strip presence that had paused for few interruptions since 1956, and just as with The Village Voice 52 years earlier, he was allowed to do whatever he wanted. Even his famous modern dance figure from the Voice strip returned to perform new interpretive dances for the 21st century.

America, the patient on Feiffer’s couch, was as troubled as ever. “I think we’re at the scariest period in our history that I have ever known,” he told the Shelter Island Reporter in 2017. “Whatever you want to say about Joe McCarthy, he wasn’t President of the United States, and he didn’t have power beyond the groups he could influence.”

In his final years, Feiffer finally began to slow down, unable to read more than a paragraph at a time before the text blurred out of sight. Nevertheless, Feiffer, in the 2017 interview, said his life was in its “best and happiest and most productive form.” It was a state of bliss that he owed, as always, to comics. “With them,” he wrote in The Great Comic Book Heroes, “we were able to roam free, disguised in costume committing the greatest of feats — and the worst of sins. And, in every instance, getting away with them. For a little while, at least, it was our show.”

As he told, Robey in the 2017 interview, “When I sit at my little table, I’m 25.”

Feiffer is survived by his wife, Joan (JZ) Holden and his daughters Kate (b. 1964), Halley (b. 1984) and Julie (b. 1994), as well as granddaughters, Maddy Alley and Eylah James Feiffer.

The post Writer, cartoonist Jules Feiffer dies at 95 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment