Peter Kuper’s latest work, Insectopolis: A Natural History (W.W. Norton & Company, $35) is an absolute triumph by a master practitioner of the comics form. It is the jewel within the crown of this unrivaled artist’s lengthy career — a work of immense scope, depth, creativity, humor and heart.

Although educational in nature, Insectopolis is a marvel that can be enjoyed by anyone. Insectopolis leaves behind the pedantic monotone of most educational comics to open the reader’s imagination into the wondrous, kaleidoscopic and cacophonous world of insects — a riveting world teeming with life and drama that may otherwise have tragically gone unnoticed.

Kuper deftly spins a delicate and thoughtful web of scientific fact, artistry, history, evolution, culture, politics, war, literature, art, architecture, film, music, toys, and the popular imagination – showing us how human history is both indebted to and inextricable from insect history.

What in the hands of another artist might have been a cliché, overwrought, prescriptive text full of talking heads, in Kuper’s hands is a transformative and immersive three-dimensional experience into Earth’s past and humanity’s potentially cataclysmic future. Radically casting aside the human perspective for that of the arthropod, Kuper takes the reader on a one-of-a-kind, unforgettable tour of New York Public Library’s Insectopolis exhibit.

Kuper’s intricate and visually-stunning work is incredibly easy-to-read, guiding you through each morsel of information and every page turn with expert skill. His artistic sleight-of-hand will so thoroughly absorb the readers into the insect world that they may entirely forget that they may have a long-standing history of being entirely disgusted by insects.

Kuper brings his signature radical perspective adjustment not just to the insect world, but to the inscription of natural history. Throughout Insectopolis, Kuper not only highlights luminary naturalists like E.O. Wilson and Rachel Carson, but also pioneering naturalists like Charles Henry Turner and Maria Sibylla Merian, whose insights and research have been overlooked due to prejudicial human ideologies around race and gender. Throughout Insectopolis, Kuper works to reinscribe the forgotten aspects of natural history for the reader.

I recently sat down with Kuper to discuss his latest staggering feat of art, his revolutionary artistic perspective, and his robust three-decade career.

This interview has been edited and condensed for the purposes of clarity.

IRENE VELENTZAS: Let’s begin with Insectopolis. Can you give us a general understanding about the project and its inception?

PETER KUPER: Let's start with why I was even inclined to do it. I have been interested insects since I was about four. I was born in New Jersey, and the cicadas came out in 1963 — I think it was Brood 11 — they come out every seventeen years, by the millions and they were covering trees. I know a lot of people's reaction to seeing something like that is total horror, but for me it was complete excitement. From that moment on, I found them incredibly fascinating.

I think it's the same mentality that makes one interested in comics, or science fiction — seeing the stars in the night sky or Spider-Man swinging by a web — they touch on a sense of awe and wonder. What would later turn into my enthusiasm for comics started with my interest in insects. I went from spiders to Spider-Man. But it did originate [with insects], I had a sign on my desk that my father had printed for me when I was six that said “Peter Kuper, entomologist.” I collected insects and I loved them to death — I apologize to all the ones that I literally loved to death. I was just fascinated with natural things — the color of butterfly wings and the venation of dragonflies’ wings, the Praying Mantis in our garden — and wanted to study them up close and have direct contact.

I still keep the Golden Nature Guide insect book my parents gave me when I was, probably five, on my desk. It’s got my name scrawled on the top. It’s a talisman for me now. I've thrown out so many things from my childhood and I almost threw this out. Now I keep this book close — it’s an important building block of my history. So I got into comics probably when I was seven. I saw Jack Kirby and Stan Lee’s Thor, and was instantly attracted to comics, although my insect interest continued. So there were parallel passions there.

As I became a cartoonist, as an adult, I realized that I could find a Venn diagram between these dual passions. I first brought that into my work via my adaptation of The Metamorphosis by [Franz] Kafka. My love of insects worked into the sympathy I had drawing Gregor Samsa.

Then, with my book, Ruins, I really dove in. That book came out of my time living in Mexico, and actually raising monarch butterflies, and then visiting the monarch sanctuary where they go by the millions. Seeing it firsthand, I realized that would weave into the story as I developed Ruins. I had every other chapter focusing on the monarch butterflies’ migration in that book. A few years later I did [Joseph Conrad's] Heart of Darkness — which was loaded with insects in the background.

I was making my way towards Insectopolis. After I finished Heart of Darkness, I proposed to the publisher that I was going to do kind of a "Guns, Germs, and Steel" history of insects. It was inspired in part by an article I’d read in the New York Times magazine on the insect apocalypse. I had also read Silent Spring by Rachel Carson and Elisabeth Kolbert’s Sixth Extinction, so I wanted to cover aspects of all of those books in a graphic novel. My editor at Norton said he wasn’t interested in what was, at the time, a pretty vague idea. [Laughs.] I kind of went away dejected, but I sat down with my sketchbook and started roughing things out.

I wanted to create a graphic novel that surpassed the knowledge I had at that point that would take a huge amount of research. I wanted to come up with storytelling that I hadn't figured out yet: where I'd do something, with panels are crisscrossing through time, the history was going to merge, and … I was super vague on what that meant! My brain was screaming, “Be brilliant. Do something you haven’t figured out, that you don't know you can do yet,” which also felt absurd and impossible.

By chance ran into a Harvard professor, Maya Jasanoff, who had written the foreword to Heart of Darkness for me. She came by my studio and we were talking about this project idea, and she said, “Oh, you should apply for a Cullman [Fellowship at the New York Public Library],” which she had gotten previously. I was aware of the fellowship because a number of people I knew had got it, like Ben Katchor, Gary Panter, and Dash Shaw. In fact, I had written a few recommendation letters, one for Frances Jetter, and she had gotten the fellowship few years earlier. So, I went down to the library, I looked around their collections, what books they had on insects and entomology. I also got some pointers from people who had gotten the fellowship. In a one-week period I managed to throw together a proposal and am still stunned that it came together.

They called me and told me that I had received the Cullman in February of 2020. It would start the next September. Then, the collapse of the pandemic occurred. Aside from the growing pandemic anxiety, I was rather freaked out getting the fellowship, because I really did feel like it was a bit above my pay grade. The guy who had won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, Gregory Pardlo, was getting it, Hernán Diáz, who subsequently won the Pulitzer for the book he wrote [Trust] during our Cullman was there, also New Yorker writers and famous historians etc. — a lot of amazing people.

Part of the fellowship is that you get to interact with everybody. But with COVID, they informed us [there would be] no interaction whatsoever. Also, the library was closed to the public. You would have to mask up everywhere but your office. It came close to being entirely cancelled. They even had shut down — in mid-Cullman — the group who had gotten it the previous year. So, my group just squeaked through. I get up there to the library and I just think, “This is so typical.” Like the generation that arrives at the beach just in time for the medical waste to wash up. I felt like crying over what wasn't going to be possible, interacting with the other scholars.

I was walking around that empty library and it was like a haunted house. I went to the Map Room to find out if they had a map of the monarch [migration]. [As] I was waiting for the librarian to come out with the material, I was looking around this incredible library architecture and was hit by a creative lightning bolt. I suddenly realized; this seemingly post-apocalyptic environment could be the perfect backdrop for my story. I started photographing the room and then I ran up to my cubicle and I began making drawings coupling the environment with the insects. I didn't know what chapter the image would land on, or how I was going to break the story up. It was just all a lot of estimation. I just thought, “Dragonflies or dung beetles would be good insects to cover” and started making drawings of them moving through the empty library.

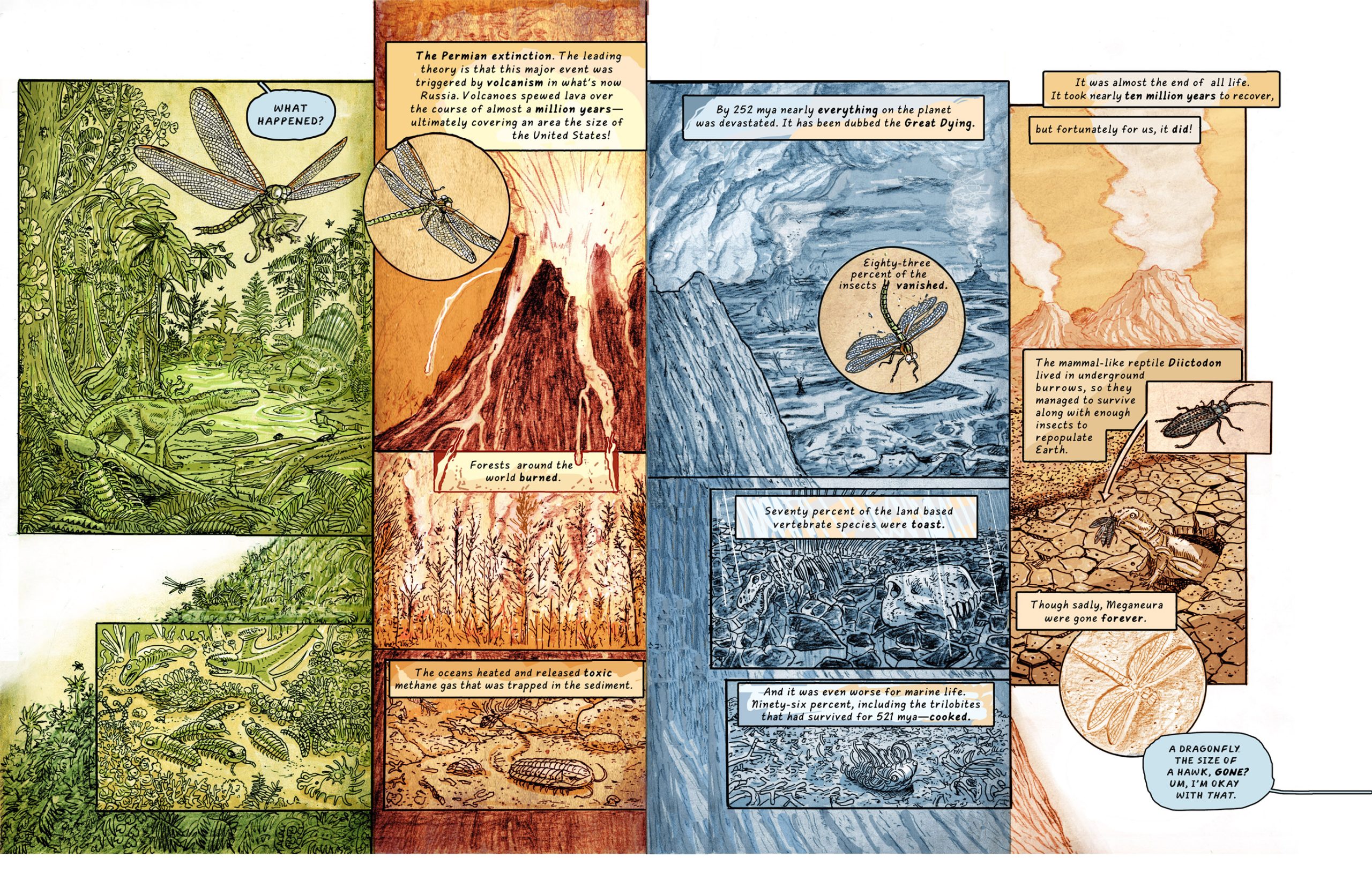

As I began developing on it, I reached out to entomologists for advice. They would tell me, “Well, you're going to have to cover the Permian extinction and the Eocene.” Then I had to educate myself on those subjects and figure out how the pieces would fit together.

You have all of insect-kind to choose from this book. How did you decided which to highlight and how to order those sections? The ordering throughout the book feels so fluid, but I'm sure that took some real thinking through what the book would become.

The curious thing is, I was guessing as I went along. I didn't know what would make a good chapter or where any individual chapter was going to land. I worked on them in a modular way and sometimes jumped around a little bit. I would start exploring a particular insect and think “Okay, dung beetles are going to be good because it's the scarab, and there's going to be Egyptian history in there — that goes into all sorts of things that should be interesting.” Then I'm looking into what they have at the library to back that up — part of the Cullman is utilizing the different areas of the library.

So, when I studied, let's say, Maria Sibylla Merian, who was a 17th century naturalist, they had her original hand-colored lithographs from the early 1700s that I was allowed to page through. I would find somebody like that and what insects they might have been interested in. Just to keep moving forward, I would do individual [pages] like a dragonfly flying up the staircase one day, and then the next day a drawing of a dung beetle rolling dung ball down the hall the next. I’d say “I'll figure out where they will land later,” [or] “I think that will make an interesting chapter,” but I wasn’t really sure. This completely broke the pattern that I had in most of my other books, where I map out a book carefully beginning to end. Normally I would do thumbnail sketches on an eight-and-a-half by eleven-[inch] sheet paper that has fifty pages in little squares, and I write down what's going to happen so I know where the page turns are and all that.

With Insectopolis, I was figuring things out one spread at a time. I would not necessarily know where the next page design was going or even where the story was going to end. It was much more like jumping without a parachute. There's a kind of a terrifying aspect creatively to do it that way, because you're just wondering, “What if I go wrong?” and “What if I have to just throw out a lot of work?” The strange part was I threw out virtually nothing, almost everything that I guessed at somehow pieced together. It was a lot of more of a general conceptual approach to it, rather than clearly figuring it out how it was going to work in a linear way. I think that's partly why I managed to keep engaged with the book over so many years.

If I was researching somebody, then I'd learn some surprising turn of events. I had no intention of doing Osamu Tezuka, but then I found out that he named his animation studio Mushi Studios, because Mushi means “insect” in Japanese. He went by Osamu “Mushi” Tezuka when he was younger, literally adding “insect” to his name because he was such an enthusiast. I stumbled upon that in my casual research and happened to reread Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics while I was working on a chapter, which has a whole section on Japanese comics and their storytelling. I thought, “What if I draw Tezuka’s biography in a manga style and have it read it right to left rather than left to right? What if I could force readers’ eyes to do that mid- story?”

Not calculating things so much, I was surprised by what happened each page. In the same way that’s what potentially happens with characters where they start talking to you and you really feel like you're being informed by them in writing the dialog. I think it was Graham Greene that completely refuted the idea that your characters come to life and start talking to you. And yet, I have had that experience many times, and that’s one of the joyful moments in a creative process of the writing. When I feel like I come upon a stuck point and I'm not sure what the character will say next, and the character just says, “I don't know what to say,” that's the line I use.

I was really interested in your Tezuka spread because there's this dynamic act of consumption that you show happening in terms of Tezuka’s work. You picture him consuming all of this information, which is essentially how his art is born. So, I wanted to ask you about the parallel of that process in your own work. Was it like you had been taking this information in for decades and all of a sudden it synthesized as you were creating rather than being on, like you say, an organized, systematic kind of journey?

Absolutely. There were so many things I didn't know about insects. So, it was the pleasure of going to school, trying to become an entomologist while I worked on it. The project was dangerously close to taking a course in biology. My inability to sit in a science class and learn the Latinates and all the things that come with a college degree had dissuaded me from trying to be an entomologist. But here I was, studying up; I would have a documentary playing about the history of the planet, or the history of the six extinctions, or whole hours of documentary on dragonflies or dung beetles. I was just completely marinating in all this information. I've been interested in insects for so long, but until Insectopolis I had only studied them casually.

During some of my travels — and my travels with my wife and later with our daughter — involved very specific insect explorations, like going to Monarch Reserve in Mexico, or going to a butterfly sanctuary somewhere in Malaysia. So that fascination was always there. But then there's so much deeper learning about the inner workings of arthropods — the process of a monarch butterfly when it goes from egg, to caterpillar, to when it's in the chrysalis. For example, learning that in the chrysalis the caterpillar breaks down into a liquid form and reconstitutes as a butterfly — there’s bottomless reservoir of new information, which I [also] find to be true in studying comics. No matter how much I investigate, there's no end to the study — in comics, comic strips, in the history of the artform and art in general.

Your research process, asides from having grown up with this, also seems to have been very multimodal and experiential. Insectopolis includes maps, podcasts, documentaries, insect sketches, and photographs. Can you tell us about your about synthesizing those pieces of information to create a comic?

One of the things that was so great in this project, and in a number of other books I’ve done, is encountering things that I don't necessarily want to draw. Like doing architecture would not have been something I would have said, “Yeah, I'm going to be really excited about carefully drawing a Beaux Arts library interior, or for that matter drawing buildings in New York. What I found was when I was working on projects that pushed me to say, draw a library ceiling, or a building with a million windows. that I'd start to find the joy within that process.

So doing a deep dive study of science, then talking to entomologists, and then getting all this terminology, and all of it became dessert. I mean, I was learning, but it was so interesting and it didn't stop being that way, or lose any of the momentum of joy until I finished. With many other projects, as I'm getting towards completion, I'm getting desperate to be done. With Insectopolis, I actually asked for an additional six months. I was working intensely — almost seven days a week on it — and yet I didn't run out of steam, or get overwhelmed by the information.

As I worked on Insectopolis having information coming in from different areas — looking in books and documentaries, looking at art history, poetry — anything that was related to insects helped open lots of doors to ideas. I happened to look up a podcast on a guy, David Rothenberg, who makes music with the sounds of insects. I just filed that away. I reached out to him when I needed music for the QR codes that I had in an exhibition at the New York Public library after my fellowship. He responded immediately, and he let me use all that music for free. We met some months later and went out into the woods and put microphones into a lake to see if we could pick up the noises of creatures underwater. While we were doing that, I realized, I could work the QR codes from the exhibition into my book. When you’re immersed in a project there can be a lot of that kind of kismet — stumbling-upon new ideas that take you in unexpected directions when your mind is always focused on the project.

It's like the joy of discovery. This also translates to the reader, because we get this same kind of joy of discovery throughout the work.

Earlier, you said that you went from spiders to Spider-Man as a kind of natural progression, and I wanted to ask you more about that. There doesn't seem to be a lack of insect-related material in the comics industry in terms of the insect-superhero – there’s Spider-Man, Ant-Man, Black Widow, The Wasp, and many more. Why do you think the Super-insect has loomed so large in comics fantasy culture, but the regular insect has not?

I addressed that in the Ant chapter — the whole idea of gigantic ants from the movie Them! and H.G. Wells’ book Empire of the Ants. I was interested in finding how our human fears were actualized in stories and characters like Godzilla. The way scientists develop things that run out of our control, like nuclear weapons, which is perfectly relatable right now, of course, with AI. Stan Lee threw radiation at everything — there's a container with radiation and it bumps Matt Murdock in the head, and BANG! you get Daredevil, “The man without fear!” I really think it was part of a way of addressing the fear that people had, with the A-bomb and radiation coupled with insects. People turned [that fear] into powers, like Giant-Man and Ant-Man, or monsters.

One of the earliest drawings I did [for Insectopolis] was of these giant ants entering the library, and I had not completely figured out why I had giant ants there. So, later in the book I just threw in, having a small ant asks one of the giant [ants], “Why are you so big?” The big one says, “Diet and exercise. Just kidding — I have no idea.” I later learned, 300 million years ago, there was a dragonfly ancestor the size of a hawk. Oxygen levels in the atmosphere during the Carboniferous Period was 35% as opposed to the 21% we have today. It was so oxygenated that [insects] could handle being a larger size, plus there were no other predators at the time.

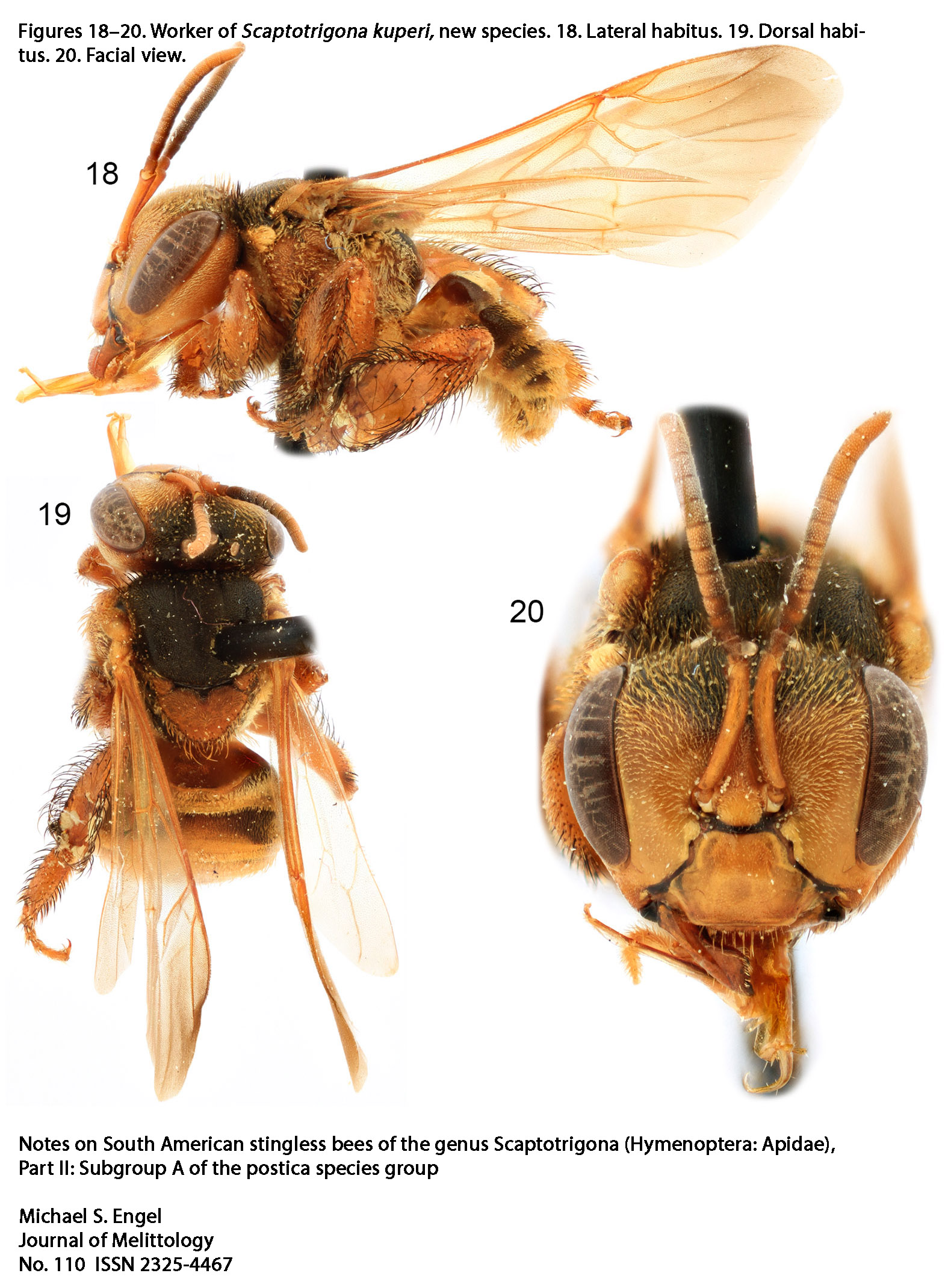

H.G. Wells wrote Empire of the Ants at the turn of the last century that was a response to these whole worlds that we barely understand. We've only identified about 20% of the insects; entomologists are constantly discovering new species. Michael Engel, one of the entomologists I was getting entomological advice from, was out researching in Ecuador when he discovered a bee and named it after me! The Latinate is Scaptotrigona kuperi. They just add a little “-i” at the end of Kuper to make it a Latinate. One of the joys of my life is to have a bee flying around that has my name attached to it.

That's amazing. It's very interesting, you're talking about this almost fear of dissolution that humans have, and this threat of contagion as well, in your book. But art and science, insects and invention, have all intersected throughout human history to bring us the technology that we have — from the helicopter to bioluminescent screens and more. There's not just fear, but there's also observation, and from there creation. Where does that push us within those realms?

We’ve taken a lot from observing insects. Dragonflies can turn their heads almost 360 degrees, detaching and reattaching it with fine connectors. People looked at that to develop Velcro. They're looking at how the wings work on a dragonfly to develop all sorts of flying robots. I'm sure this will all work out perfectly to benefit humanity. But if you're a Black Mirror viewer, you know that robot insects are going to be problematic.

And of course, in very real helpful terms, insects are doing a million things to help us. They’re aerating the soil — ants, termites, and the cicadas do that. What so many insects do in their natural course of existence, though the benefits aren’t obvious to us, are hugely important to a functioning planet. That's why I quote E.O. Wilson at the beginning of the book, [who said]: “If all mankind were to disappear, the world would regenerate back to the rich state of equilibrium that existed ten thousand years ago. If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos.” There’re all these ways that insects are making the world stay healthy and there're all these ways we can learn from them. Of course, insects can be a destructive force in our lives — termites can cause billions of dollars in damage to homes, mosquitoes carry disease. There are two sides to that coin.

There were hundreds of years of misinformation [about insects]. For example, believing the metamorphosis of an insect, the process where it went from egg to caterpillar into a chrysalis and then became a butterfly, were all separate creatures, not just stages of the same insect. Socrates, in about 400 B.C.E., thought that they were each different animals and that theory held for centuries. A maggot looks like one thing, and then next thing you know it's in RFK Jr's brain, and then he morphs into something else!

It was Maria Sibylla Merian, who in the 1600s, determined that the metamorphosis process for butterflies and other insects was just all stages of one insect. Since she was a woman though, her theory wasn’t completely embraced for another hundred years. Until the microscope was invented, there were so many other things people misunderstood about the natural world. For example, it was assumed that the head of a bee colony just had to be a king, until Jan Swammerdam got a closer look and realized it was a queen bee. Most insect societies are matriarchal.

You mentioned two things in your answer that I’d like to explore further. One of the things was that termites will eat your house. If insects are out in their natural habitat, I won't bother them, but if they're in my habitat, they’ve got to go. But your book reminded me that it's all their habitat. A lot of your work explores the idea of boundaries and maybe their superficiality, their tangibility, and their enforcement. So, I'd like to ask you more broadly about that concept of mobility – what or who is moving through space and what obstacles they're encountering – and the concept of borders, whether its insects taking over the library or a national border, like we see in Ruins. Can you tell us more about constructing these boundaries and playing with the idea of boundaries in your work?

As someone once said, "If you ever see a straight line on a map, you can bet your ass whoever lives there didn't make it!" I have a scene in Ruins where the monarch easily crosses the Rio Grande, but people are trying to cross into the United States and getting nabbed. There are certain things that create a [natural] border, like a river or a mountain range, but there're a lot of straight lines around the world that are utterly artificial.

In the animal world, there are some very real lines. An ant can go from one colony to another, they can travel up to 200 miles, and then step into another colony that’s related and work together. But when they step past a certain line, they will hit a place where they're in hostile territory and will be killed immediately. Mark Moffett — who is the expert on ants and studied under E.O. Wilson — mapped this out and found that there was a literal line that would be the point of no return. I definitely found interest in that examination, and how these societies coexist in the insect world, but also how there were lines they couldn’t cross.

You don't just cover territorial or geographical borders; you also cover ideological borders and that kind of social mobility. In Insectopolis you show the idea of ideological borders through Margaret Collins and Rachel Carson's inclusion into the annals of natural history. While telling their stories, you move them backwards and forwards in time from young girls, to women, to young girls again. Can you tell us about constructing this fluid mobility and its intersection with social mobility during their time?

This is the joy of comics — film does this well too. There's something about seeing somebody age before your eyes, which can express so much. I stumbled upon this approach in Insectopolis to tell a couple of biographies. Margaret Collins was the first African-American entomologist to get a Ph.D. So, to tell her history, I started when she was younger. She was a prodigy, she was going to college at 14, and then got up to the barrier, the border, of what you can do as a woman. In her case in particular, her professor — who was very encouraging of her to go into the study of termites — said, “I don't want you on the expedition because you're a distraction to the men-folk.” I told her story alongside of Rachel Carson, who wrote Silent Spring, an important book in the environmental movement. I had them start as children together and slowly age, then revert back to children.

In Insectopolis, I didn't want to just cover the [people] everybody knows [like] E.O. Wilson. So, I looked for entomologists and naturalists who were less well known or forgotten through time. Somebody like Charles Henry Turner, the first African-American, male entomologist to receive a Ph.D., was suppressed in his work his whole career. And yet, he did these transformative experiments that people thirty, forty years later were re-discovering and then going, “Whoops! Looks like somebody else figured this out before I did.”

While reaching out for advice I discovered [that] entomologists are like comic fans. One of the comparable aspects is that entomology was long considered a low science, the same way comics were considered low art. There were arguments between people like E.O. Wilson, who was at Harvard, fighting with James Watson, who discovered DNA, over the importance of Wilson’s work. Watson was saying field science is dead, it's all going to be in the lab. He blocked Wilson at Harvard from hiring people who would have a more traditional science approach. And they fought it out for years.

There are hierarchies in art and science, then you have the added bonus of being a woman, or being a person of color, and that blocked you from being able to move forward. I was interested in who got lost in history that I could highlight. That again was another reason to do the book, because that spreads into different areas of social commentary. That’s something I found a lot with my work in general. Like in Ruins, just tracking a monarch butterfly’s flight wordlessly to Mexico, what it naturally passes during its migration– Three Mile Island, strip mining, over migrant farm-workers, or the Lower Ninth Ward in New Orleans post-flood, or gang wars in Laredo. A natural commentary exists showing contrasting worlds and I'm merely illustrating them. This allows me to have another layer or two to my stories.

In discussing the intersection of the seeing, discovering, inventing and how science, literature, or art all do that, you mentioned the idea of the microscope being used to look at things more closely. I'm very interested in the kind of perspective that you create in all of your books where your viewpoint often simultaneously functions as both microscope and telescope. You show us a big spread, but then you're also punching in on all these things that would go unnoticed if we're just looking at the landscape. Can you tell me about constructing and presenting these simultaneous, shifting viewpoints for the reader?

With Insectopolis you can sit down and read through it in about 45 minutes just with the word balloons. Then, you can reread it slowly and discover additional layers like the hidden QR codes – which by the way my very astute copy editor didn’t even notice until I mentioned them — to get a bonus reward and more information. I love the notion of a work unfolding, where you’re finding new layers on a second read. There are a number of books that I re-read periodically, like Art Spiegelman’s Maus, and I keep finding something new each time I read it. There was a lot of subtext and context that I wanted to have in [Insectopolis], so I populated the pages with a dense amount of information. If you’re in the mood, you can read it carefully and see all that. If you aren't, you'd still get a really solid through line reading the word balloons only.

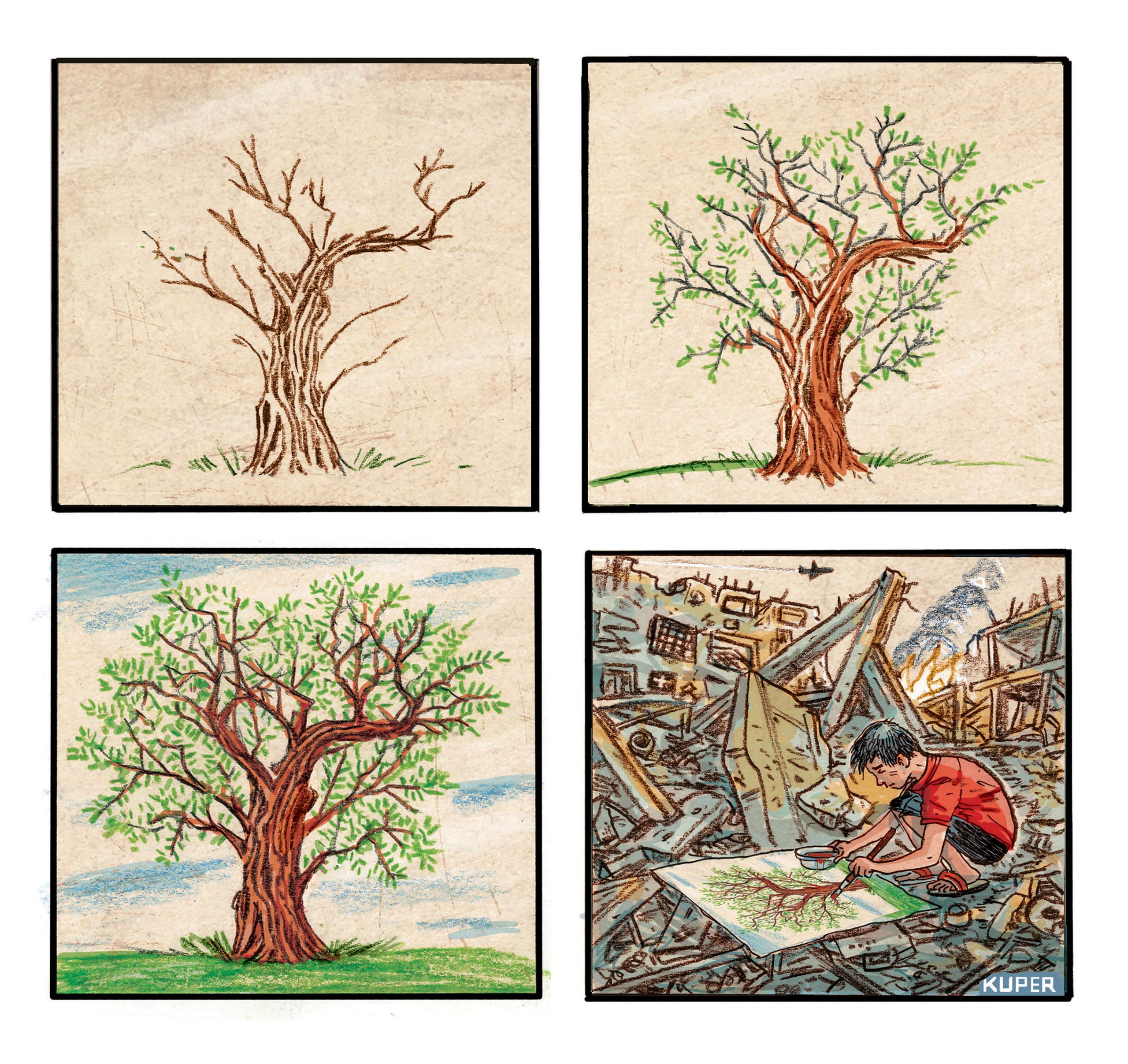

I’m interested in ways one can layer the visuals, things the reader many not be conscious of except in the back of their minds. There's the Kafka story I adapted called “The Trees,” where I turned this short story describing trees in the snow into a story about homelessness. There's a last shot where you have an ambulance pulling away and its back doors create the image of a skull. Things like that, inserting images that only your subconscious mind may see gives the art a richer texture.

There is so much going on visually in all of your books, but to me Insectopolis is the ultimate act of juxtaposition. Your work relentlessly juxtaposes several types of media, communication modes, and artistic tools. What are you trying to achieve with this almost overwhelming amount of juxtaposition in your work?

Avoid boredom. [Laughs]

Well, stylistically, some of it, I can't fully control. I’ll get tired of a style after some years and want to change and explore something new. With my Kafka adaptations, when I read the work, it rang the woodcut-style bell to me of Frans Masereel, Lynd Ward, and German expressionism. That's how his stories spoke to me. When I'm doing something like Insectopolis, each chapter has the opportunity to do that. I get to juggle approaches, especially now that I've been doing this for decades and have a range to choose form. I was looking at Saul Steinberg's and [Pablo] Picasso’s work in art school. You're seeing these [artists] doing a little painting, ceramics, sculpting, woodcuts, whatever. There're no boundaries on artistic style. Steinberg, for me, was an artist who made me reconsider my entire way of thinking.

When you're starting out, everything that's coming at you will get into your fingertips. I was an inker on Richie Rich when I was eighteen [years old]. That was one of my earliest jobs. So, I was going over the lines of a very mediocre Richie Rich artist because they didn't trust me with anybody better. But it was still helpful [because] I was learning how to ink. But like everything you learn when you’re starting out, it gets into your style. I cannot help but draw a kind of a Richie Rich hand occasionally. There’re certain anatomical motions that just got in my fingertips, because I spent a year and a half inking them. So, I learned about line weight and things like that, but I also got some stylistic ticks.

Now, I have all of that at my disposal. So, if I get an idea and I want to go in a direction, I'm not worrying about somebody saying, “He has no idea stylistically what he's doing.” It's a little bit over here. It's a little bit over there. If you look at my sketchbook, you see it's the mash-up of styles, because that's where I did my experimenting. But now, I feel like all of those are me, because it's all been funneled through my point of view. So, whatever tool I'm using, it's really the idea that matters — I’m not worrying about maintaining a particular style. To me, style is like clothing: if you wear it too long, it starts to smell, and it goes out of style.

I found certain art forms, like stencils and spray paint, that were just magnificent for their surprising results, they kept me on my toes. Like working with linoleum, where you work in a flipped image that you later print – I didn’t know what I was going to get until I was finished. I've done three whole graphic novels with stencils and spray paint: The Jungle, Sticks & Stones, and The System and a children’s book called Theo and the Blue Note. It was a very laborious process. I did thousands of illustrations that way, and that was the style I was known for, but enamel paint is toxic as hell and at some point, that approach just didn’t speak to me anymore.

One of the things that definitely did happen as an illustrator, was that people wanted me to have a style they could depend on. I eventually developed a style that gave me the latitude to experiment. I arrived at an approach where the stencils and spray paint were the base, but then I could put collage in there. I could use watercolor, colored pencil, and mixed media that kept me engaged and it remained surprising.

I have many different interests. That is evident in wanting to do autobiography, and adaptations, and going into science. If I do one thing too long, [I lose interest.] Wordless comics I remain interested in – and very fortunately, every week I get to do one for Charlie Hebdo. But, if that was all I was doing, there would be some writing I would want to get in there. So, a lot of it has to do with fearing the boredom factor that could creep into my work if I don’t experiment.

I've seen that in artists. You see somebody who's doing something that's magnificent, like Bernie Wrightson, who just clearly just got bored with what he was doing and began batting it out doing superhero work he clearly found tedious. That’s what I want to avoid.

That makes sense. You want to keep your point-of-view fresh. You want the energy of your art to translate to the reader. By using all of these artistic mediums, your work also embraces a synesthetic artistic approach. For example, you use scratchboard in works like Kafkaesque, The Metamorphosis, and Heart of Darkness, giving them a textural feeling. In Diario de Oaxaca you smear the red “juice” of the cochineal insects onto your pen and ink pages and you use watercolor shapes to evoke a location’s “Odorama.” In The System, you wordlessly transform an incoming subway train into a Wilhelm scream using stencils and spray paint, which also have a visceral effect. How do you approach drawing all of those senses together or transforming those senses through the visual medium in your sequential narrative work?

The boredom factor aside, I want the art to reflect the story I’m trying to tell. For Kafka, I used scratchboard to approximate the woodcuts of his era, whereas stencils and spray paint were very potent to tell a story like The System, which evoked the graffiti that was ubiquitous 1980s New York. With Heart of Darkness, the story being told in real time was done with pen and ink and digitally tinted. Then when we go into the past story that's being told by Marlow, I did that in black pencil and watercolor, so it looked more like my sketchbook. That felt right because Conrad kept a sketchbook during his travels in the Congo and I wanted to give the book that quality of travelogue.

I'm interested in your process of foregrounding your artistic tools and the materiality of your work. For example, Drawn to New York's cover showcases a Micron 05 archival ink pen, a pencil, and a paintbrush, with the Chrysler building also becoming a pen on the front cover. On the back cover, you transform the city's architectural landmarks like the Guggenheim, Statue of Liberty, Twin Towers, Flat Iron Building, Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building into paint splashes. Throughout the book, you also use your sketchbook as a frame for your double page spreads. Why do you foreground and transform your artistic materials in this way?

Well, my sketchbook is hugely important to me. There wasn't any indication that I was going to be a cartoonist when I was in high school. My sister bought me a sketchbook, thankfully, when I was about 15, so I started drawing more regularly.

But before that, there was an event that had a big impact on me. I grew up in Cleveland and I happened to meet Harvey Pekar, maybe in 1971. His paperboy saw that I had some comics and said, “There's a guy over in that building with some comics.” I went over – at that age I felt that it was my right to know anybody that had anything to do with comics. I rang his doorbell and he let me come up into his apartment. I mean, I was maybe 12 [years old] and he was an adult.

I think there was a copy of Batman on his coffee table, then he showed me an original Robert Crumb drawing he owned of a guy peeing into a toilet with his genitals out. This was absolutely mind-blowing for me at the time. I wasn't of age to buy underground comics, and it thrilled and shocked wonderfully. Crumb was friends with Harvey, so when Crumb came through town in 1972, I managed to trade him some 78 RPM records for doing the cover of a fanzine that my friend Seth Tobocman and I were publishing.

I went over to get the art and he hadn't started it yet. He was staying at Harvey Pekar’s and he said, “Just come back in a few hours and I'll be done.” I was young and confused by the process — and I thought like, “What if he doesn't do it?” So, I said, “I'll wait.” This is thirteen-year-old-me, so I'm just staring at him, sitting on the couch, and he's starting the cover, and I come over to look. To keep me entertained, he gave me a sketchbook to look at, and it was a revelation. Those are now published, incredible things. I spent the next hours, as he worked on this piece in front of me, slowly going through the sketchbook and it was life-changing. My mind was completely blown by the idea that Crumb was able to draw straight pen and ink, nothing penciled, drawn both sides of the paper. When I got my first sketchbook, I’d draw one drawing in the middle of the page and sign it like it was precious!

Another important guiding light was New York City and my annual pilgrimage to the New York Comic-Con. I went to my first one when I was twelve [years old], in 1971. It was a very, very different world of comic conventions. It was a small group of people, maybe a few thousand people, and you’d go up to the artist and meet them. I walked around with a sketchbook and got sketches and autographs from artists like Sergio Aragonés, who drew me several sketches. I got to see all that sketching and visiting New York, it was like a collision between those wonderful things. I was ready to move to New York then and moved there from Cleveland when I was 18, which was my first possible opportunity.

During my first spring break at Kent State, I hitched to New York with my sketchbook– which I was drawing in more and more. I can draw a straight line from looking at Crumb's sketchbook to doing the same myself. When I got to New York, I went door to door to animation houses. I said, “I'll do any work. I will paint blue backgrounds, no problem.” And Zander Animation said “O.K.” I was thrilled! I had been in a fairly deep depression in Kent because, I just saw the world that I was not going to fit into. I believed strongly, “I have to make it in New York or I’ll wind up a deflated football in a gutter.” The job offer was a lifeline, so I came back [to Kent] with my depression lifted.

I moved to New York that June, went to his office, but he wasn't around. I kept going back. Weeks went by. Then, when I finally met the boss, he had no memory of offering me a job. The animated film Raggedy Ann and Andy had finished and he said “Animation is in a downward turn and there's no job.” I said, “Well, what am I supposed to do?” He was like, “Call me in six weeks.” I just did that until I think the phone stopped ringing in his office. Though he's not somebody I’ll thank in my Oscar speech, he was one of the reasons I got to New York. If I hadn't had a job offer, I don't think I would have moved.

When I moved to New York in June of 1977, there was a garbage strike that lasted for two weeks. The entire city had rats everywhere, mile high garbage, and it smelled like you would imagine in the heat of summer. There was a blackout in July and complete pandemonium, just immediate rioting and smashing the place up. Son of Sam was running around shooting people. I had moved into a place in Brooklyn not far from where the shooting was going on, and still my attitude was, “This is amazing!” At 18, it was very exciting, and scary, and all the things that come with that. At that age, I was walking a line of being scared but feeling very alive.

So meanderingly answering your question: the sketchbook was hugely important and the tools, pens and pencils, are part of that story. Making the Chrysler Building, one of the most beautiful symbols of New York, into one of the drawing tools [reflects a piece of] New York that is so important to me: in my comics history of coming to the comic conventions; in terms of a general history of the artistic atmosphere of New York, where all this art is going on; and the electric vibe artist [bring to] it like [Jean-Michel] Basquiat, and Keith Haring, and David Wojnarowicz. The street art and the graffiti — subway trains that had these magnificent murals on the outside including spray paint versions Vaughn Bodē’s Cheech Wizard and things that were referencing the comics that I loved. All that mashed together in a happy mix of inspiration.

Sketchbooking was built into [Drawn to New York] and so those tools in New York as a sort of an instrument of my inspiration were also part of it. In fact, one of my earliest books was New York, New York, published by Fantagraphics in 1986, so most of the comics I was doing at the time were about New York and all the imagery I related to recorded that.

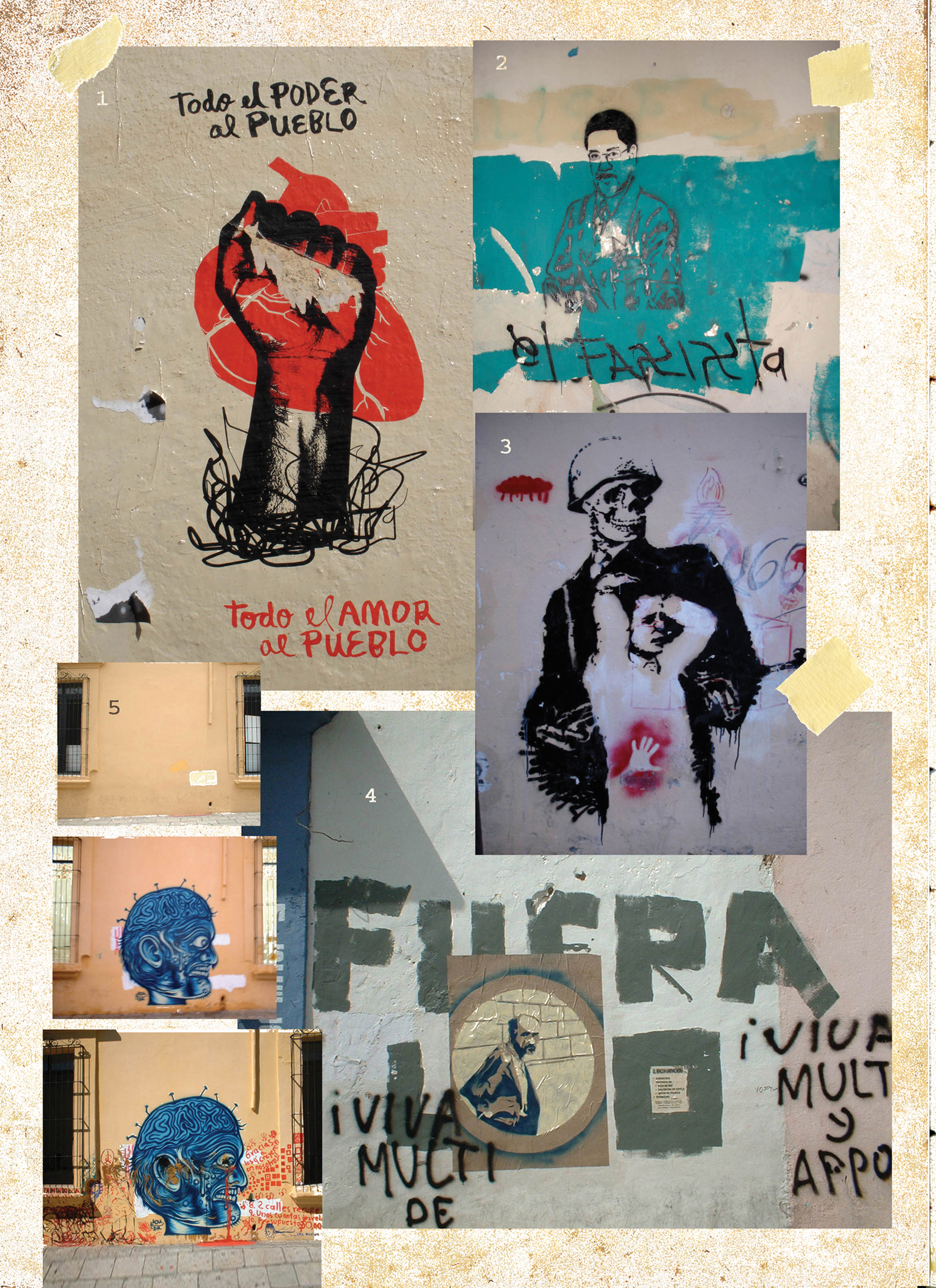

A couple of times, you've mentioned your use and reproduction of the tools of street art, which I’d like to ask you more about. In Diario de Oaxaca you capture street art by photographing it, but in doing so, you change it from this wall size image into an image that fits into the space of a couple inches within a printed book. You also collage many of these street art photographs together, whereas typically you would walk through a city viewing street art through space and time. There's also a sequentiality around street art that you capture as it changes from a blank wall, to a piece of art, to a piece of art that has art on top of it, to being a blank wall again. Can you tell us about using and transforming street art in your work?

This is going to tie into World War 3 Illustrated. Seth Tobocman and I started World War 3 Illustrated when we were we were both in art school at Pratt Institute. There was so much street art being produced on walls, on posters on lamp posts, representing huge protest, certainly in our eyes, against the direction that the United States was going as we headed towards having Ronald Reagan as president, the very dangerous Cold War, and the hostage crisis in Iran. There was a “rah rah to war” we wanted to fight against.

There were lot of things that people were talking about artistically on the streets, and sometimes in galleries, creating art commenting on it. But, with the first rain, the posters would wash away. An advertisement was put over the Keith Haring’s subway chalk drawings, graffiti was scrubbed off the walls, protests were being erased, and so a lot of history was being erased. The magazine was a way to codify [the history] by recording it, getting hold of the poster from the artist and printing it. Maybe only whoever saw the WW3 Illustrated, or picked up Diario de Oaxaca was going to see that, but at lease that history was recorded somewhere. In Oaxaca, the graffiti would slowly morph as people either added to it or it was painted over, which happened a lot. It’s that whole action that the governments would have of eliminating something, erasing it, so that it that can be ignored.

There were lot of things that people were talking about artistically on the streets, and sometimes in galleries, creating art commenting on it. But, with the first rain, the posters would wash away. An advertisement was put over the Keith Haring’s subway chalk drawings, graffiti was scrubbed off the walls, protests were being erased, and so a lot of history was being erased. The magazine was a way to codify [the history] by recording it, getting hold of the poster from the artist and printing it. Maybe only whoever saw the WW3 Illustrated, or picked up Diario de Oaxaca was going to see that, but at lease that history was recorded somewhere. In Oaxaca, the graffiti would slowly morph as people either added to it or it was painted over, which happened a lot. It’s that whole action that the governments would have of eliminating something, erasing it, so that it that can be ignored.

There was a strong desire that Seth and I both had of making sure that these pieces of history were preserved. What was in newspapers, what was on TV was acting like there weren’t big movements against our various wars. When we came out with a 9/11 issue, just a few months after 9/11 happened, you could not get any kind of work published that was antiwar. That's why Art Spiegelman ended up doing work in World War 3 [Illustrated], because any dissent against a rush to war in Iraq and Afghanistan was being completely muzzled and muffled. As we headed towards these idiotic wars that were damaging to everybody, except for the to say the munitions industry, there wasn’t outlets to register dissent besides something like WW3 illustrated.

So, a piece of that is to make sure that you freeze that moment so that it doesn't get erased. Then, there's also the curious sequential things that I saw with graffiti in Oaxaca, making time lapse photography. Somebody puts up one thing, and then something gets added to it, and then it builds and builds and builds, and then goes back to its original empty wall. Taking pictures of the art over time was like seeing an animated film, a conversation developing on a wall.

Yeah, it really gives a sense of time and of a conversation with something that, like you say, faces erasure. I want expand on this idea of erasure in a moment, but firstly I want to discuss the broader role of graffiti throughout your work. For example, in Drawn to New York the endpapers start with a pristine postcard and end with a graffitied postcard of New York. This made me think of places like the ancient Gates of Rome and the Gates of America on Ellis Island. Places where, through graffiti, citizens could inscribe their name, communicate their plight, and the political body could see and potentially respond to citizens’ needs. How do you feel your graffitied work is placed in the broader history of protest movements and in your own political viewpoint as a cartoonist?

Well, it goes back much further, because if you look at cave paintings you see hands painted on the walls.

Yeah, you include that image both in Diario de Oaxaca and in the Kafkaesque story “Trip to the Mountains,” which I was curious about, if you want to further speak to that.

In a lot of ways, graffiti is that that desire to say, [adopts a "Ratso Rizzo" accent] “Hey, I'm walking over here!” I'm passing through this world. It’s some mark that indicates that desire we all have to not just pass through a life and turn to dust, and not be remembered. A perfect example of that is if you go to the Metropolitan Art Museum, they've moved the pieces of the temple of Dendor from Egypt. Scratched on the temple it says, “Leonardo 1820.” This is the dream – you end up in a museum, immortalized just by scratching a mark on a wall! That thing of leaving some hopefully indelible mark.

With few exceptions, most people get — if you can use a term — erased. I mean, some things are actively erased. In fact, we're right now in a period of erasure of the most horrendous [kind] — such a frightening level of government action to see if they can't erase everything, and book banning, and even banning the term “climate change.” It's really dramatic. So, that’s what the graffiti represents in many ways, that intention of having something that will make it possible to not [get erased], to have your voice potentially heard. It's a message board through time.

I went to Berlin in 1987, before the wall came down, and it was covered in graffiti. Right up at Checkpoint Charlie there’s a Keith Haring, this huge, beautiful mural. Actually, seeing that wall, I sat down and had the complete idea for this strip I did, “The Wall,” that’s about Donald Trump. I did this in 1990 for Heavy Metal magazine, where Donald Trump becomes president and builds a wall separating the East side from the West side of Manhattan, and he gives out hats. It was bizarre how many details became prophetic. Now I feel I have to draw a new strip that undoes that!

I blame you.

I know! I can assure you there's been a couple of conspiratorial what-the-fuck posts where people are putting the strip up and are going, “Okay. What's the story? This is from 1990? How did he KNOW?” But this is the thing about science fiction, that a lot of it is guesswork. You get these [ideas] that you think are meant to amuse or they're supposed to be a metaphor. Nothing funny there.

Like art and literature can be strangely prophetic because of just the observational prowess that goes into them?

Yeah. In many ways, I look to art, and artists in general – musicians, writers, cartoonists – to figure out what the truth is, because that's getting more and more eclipsed by falsehoods that are being broadcast. I think an individual's perspective, and their estimation of what's going on, can be the closest we may come to truth in this environment. It's getting to a point where [the authenticity of] photography is completely up for grabs. You can AI whatever shit you want, and it's like, “That? That happened? Those are real?” We’re now under siege of people lying. The next day you have them saying, “I never said that,” even if it’s on film. They can capitalize on the fact that everything can be manufactured. But, if an individual artist is saying something that is their perspective, it can resonate through time and speak across generations.

[Robert] Crumb, who did the comic about America for Arcade, was prophetic and it scared the pants off of me at the time. The last panel is a baby suckling on the teat of Mother Earth, who is just about a cadaver, with the rich guy standing around. It's a fairly good estimation of where things are headed now, but he was already envisioning that in the 1970s. In fact, I got a lot of my information from comics like Slow Death. These were early environmental informants, certainly for me. Earth Day was happening and they were all on board with that. A lot of the music I listened to was talking about those things, like Neil Young’s “After the Gold Rush” has lyrics that are talking about “Look at Mother Nature on the run in the 1970s.” There was a whole movement going on that this art was highlighting.

I think about the flip-side of your point, which is: when you have manufactured photographs, video, sound clips that are artificial, then somebody can use that same tool to deceive you. That someone fabricated reality, what you're looking at is not what really happened or what somebody really documented on film. As you cover in Diario de Oaxaca, there's misinformation and disinformation in the press about what's happening down there. And yet, you create sketches and photographs, and write correspondences, documenting what’s happening. What might comics’ role be as a type of slow journalism that challenges current misinformation and disinformation efforts?

Absolutely. That's what I'm referencing: This notion that art can let us know what's going on. I mean, there are people like Joe Sacco who’s been doing that for years. I was reading Palestine when he was doing it originally for Fantagraphics as comics, and Yahoo, another one of his books. They probably weren't selling very well, there wasn't a large audience for what he was doing there, but it was a guiding light to show us what was happening. The audience caught up to him and turned to his work to understand what was happening in Israel and Palestine.

We've been doing that with World War Three Illustrated since 1979. If you look at an early issue of World War Three, it was talking about things that were developing. In 1988, we did a fascism issue that was talking about what was going on in Palestine, but it was also talking about what's happening in the United States – the seeds that were being planted under Reagan that are coming to fruition now. Those early issues were shining a light on things to come. That's definitely something that art can do and is doing. I think it's one of the many values of art, especially at a time like now, which is why the government is going to be very anxious to suppress it.

For example, Trump is now the head of the Kennedy Center, so we're going to be seeing things like Cats and not anything that has political content to it. Art scares the administration in the same way that Hitler was chasing down John Heartfield, and George Grosz, Käthe Kollwitz, and all those people who spoke out through their work. Many of them had to flee because they were under threat by the government. That could happen here again as it did during McCarthyism. Art can show the emperor has no clothes and very tiny hands.

There was the musician in Czechoslovakia, Marta Kubišová, who sang this protest song “A Prayer for Marta,” which was completely suppressed when the Soviets took over in 1968. But in 1990, when the Soviets were evicted, everybody knew the lyrics to that song. That suppressed song could not be suppressed, it was an underground classic passed around on cassettes and remained a rallying cry, even under the occupation.

The powers that be will always be scared of art and be suppressing it as much as possible, but they never fully succeed.

Just to go back to what we were saying about photography and graffiti, when I was in Oaxaca, I started doing sketchbook drawings of the encamped protesters. As I started drawing, they were definitely suspicious of me. I'm standing here on the side and I'm drawing away, and it takes hours to do a complicated drawing of the scene. The strikers sent some kids to look over my shoulder, and then an adult came over, and the next thing I know, they're like, “Oh, look at this – it's us!” and then they offered me some water. This was early on and my Spanish was very weak, so the communication was coming through my drawing and then they're smiling. Then they give me a chair. The whole time I'm getting a sunburn, but I'm putting in time and I felt very connected. When I finished there, they were shaking my hand. I walk up the street where there's another encampment and I snap a photograph of it. I got surrounded by angry protesters. They wanted my camera. I was about to show my sketchbook to explain, but they were completely suspicious. And I realized from this experience, there's something you get with time, it’s a big element there. You're putting in the time and participating.

I really feel like that’s why we're witnessing this attack on the arts and any venue for the arts – places like PBS and NPR, and the Kennedy Center. As I mentioned. [Art] is something that is frightening to [the administration] because it's not as easy to control. [Art] is outside the box of what they can completely crush, and that's been true forever. You see something on a wall – to tie it back into graffiti– what people will see will help influence their perspective. Sometimes, guerrilla art action, like the graffiti that was in Oaxaca.

That brings me to one of the main themes we see across your work. Whether it's Diario de Oaxaca, Sticks and Stones, The System, Ruins, and Insectopolis, or even your adapted works like The Metamorphosis, Heart of Darkness, and Kafkaesque. You not only show violence in these worlds and works, but also the constant threat of violence and erasure. Can tell us more about the development of these recurring themes in your work and how you navigate this tension for your characters and readers?

It probably started sixth-grade, getting beat up a lot, and reading comics, and being considered a super nerd. My father had a sabbatical year when I was ten years old and we moved to Haifa, Israel, for a year. I was an outsider and got beat up almost daily. Looking back, I’m glad it happened since it opened my eyes to a bigger world and clearer understanding of what it means to be the underdog. In general, a lot of the things that I liked were not socially acceptable. My enthusiasm for comics always felt like I was in on a secret that was so obvious. Like, this is the greatest art form, and it's being treated like it's the lowest art form. That's also true with information. Being conscious of environmental damage, was very obvious for a long time. Then you talk to people about climate change and there's a fight against any consensus on something that's so obviously is going on. So, having outsider status in different ways helped me see what was important.

The people I found interesting were ones that were getting beat up, or pushed to one side, or completely ignored, and a lot that's true with a lot of history. I found that in science fiction and with writers like [Kurt] Vonnegut who were always describing the way people related to each other, or the horrors of the world, in a comedic way. Of course, MAD magazine did that beautifully. A lot of political cartoonists like Jules Feiffer, Pat Oliphant, Conrad, Steadman, Scarfe were out there talking about inequities, but also pointing at the problems of the left too, not letting liberals off the hook either, especially Feiffer.

Do you think about how that threat of violence or erasure also impacts cartoonists and their protests? We've seen some of that in Diario de O axaca and Wish We Weren't Here. But very top of mind for me is the Charlie Hebdo attack – when the artists themselves become objects of violence and erasure because of their art. Can you speak to that?

Yeah. That’s been a part of the history of political cartooning. Cartoonists have been getting jailed for their work for years or, or attacked in some form. My cartoonist friends and I talk quite a bit about the conveyor belt of repercussions – attacks on anything that doesn't go along with the narrative that the administration is putting forward, attacks on the press. I'm keeping my eye on late night show hosts like Stephen Colbert, Jimmy Kimmel, Seth Myers, John Oliver, and Jon Stewart. That's the top of the food chain in terms of political commentary. I'm anticipating that shows like those will get suppressed, shut down, and maybe the comedians will find themselves jailed. As we're moving in an authoritarian direction, that's the kind of thing that's not allowed. You see it in the extreme in countries like Russia and North Korea, but that's the direction in the United States that we are definitely heading. I am conscious that there could be a tipping point – and by the time this interview comes out, the tipping point may have occurred. I feel like we've been teetering. There are so many different places that's going on, but on the other hand, it ups the urgency to get the work out there, and be very vocal through the work.

I fortunately have a spread of venues between World War 3 Illustrated, Charlie Hebdo, and a website called OppArt for The Nation magazine that I co-art direct with Steve Brodner and Andrea Arroyo. We’ve been doing [OppArt] for seven years, starting in Trump's first presidency. We post commentary art five days a week that includes graffiti. I post things from Oaxaca, when I'm there, or things you see in New York like paintings, cartoons, comics. It's a cross-section of political art. If there's a rally, we'll take pictures of all the signage. It's intended to encourage viewers to see that they’re not alone.

I reject the “preaching to the choir” perspective. I started cartooning because I saw people doing these kinds of things – political art. MAD magazine was definitely a big piece of that. I wasn't a member of any choir when I started reading MAD or looking at political art. That's how you get educated and form your perspective. So, for generations of people, this may be the first thing, the first time, they see something challenging the sanitized narrative. There was ongoing action in Oaxaca, Mexico, when I lived there, that wasn’t getting the attention it deserved. So, I started drawing about it, posting about it, and then writing about that work. I realized, I could bring attention to issues through my work.

The suppression of media really impacts our shared understanding of the world or our ability to even have a shared reality. I'm curious about the kind of perspective shift that you are creating in your work. For example, often you're depicting characters focusing on the wrong things or not focusing on the bigger reality. With so many things vying for our attention, how do you think about harnessing the reader's focus and being able to highlight what to focus on?

I think one of the beauties of comics is that you can have many layers going on at the same time. It's like you're standing in a burning room, the person sitting on the couch doesn’t notice there's a fire in the background. You see it, but the character doesn't. [You can] show that simultaneity, which is harder to do in just prose. Irony is a really huge, fantastic tool that you can have contrasting things, like the words say one thing and the image is showing something completely different. That can be a way to highlight the point. I'm trying all the time to figure out the best delivery system for information if I'm trying to say something.

I think humor is a great tool, and potent weapon, because it's one of the things it's harder to fight against. When you make an earnest point, it's much easier to dismiss. So that's where I think MAD has been so effective over the years. When you think about the resulting audience of MAD, that that's where you get Art Spiegelman, Bill Griffith, Robert Crumb, and the entire underground comics scene. Taking the piss out of everything, but doing it with humor and irony, that really blew a lot of young minds in the best way and got them out there doing their own thing and expanding upon what Harvey Kurtzman built.

Also, I always try to find the most engaging way to tell a story so the reader empathizes with the characters. In Insectopolis, I had the opportunity to do various forms of storytelling throughout the book. For example, I was trying to figure out how to tell the story of a cicada that is essentially alive underground for seventeen years. It's kind of a sad figure. It's lonely under there. I introduced the idea that the tree is the cicada’s friend. How get into the mind of a cicada? You think that would be incredibly lonely. So, I can do serious chapters like that, then joke about the seriousness, and roller coaster through the story.

[This reflects] my experiences studying and learning new information. In figuring out how to put it forward for a reader, you can only be guaranteed a reader of one, which is yourself. So, if you're not happy with the material, if you're not having a good time on some level with the work, you're not finding it fascinating, then you could end up with zero readership. I was enjoying the material, different ways of drawing and the exploration making Insectopolis, so I knew at the end of the day, if nothing else, I would enjoy reading this book.

Speaking of the cicada scene, I'm really interested in how you construct your physical page and panels to create central and peripheral perspectives. You enact a kind of moving upwards, where we see less and less of what's happening on the top world before the cicada reaches the surface. But you also use this technique in The System where the literal periphery of the frame is like the marginal viewpoint, making the reader search for information. How do you think through constructing the space of comics, or the space of the image, to enact this kind of perspective?

I made lots of different notes. There'd be written notes, and drawn notes, and a combination of the two. For example, the one with the cicada, I actually went outside, I was in the country, and I was sitting in the yard listening to them. I was thinking about the underground part, and then start fiddling around and doing these very loose sketches. Often these early things, the little sparks, will end up in the final product. The best of it is when, as I start doing that, the sparks turn into flames. I had the idea, “Oh, the tree is going to be talking to the cicada.” The tree’s above ground and the cicada’s deep underground, so to show this dichotomy I’ll make the panels vertical. Readers will see all the weather changes going on above ground, but underground it’s stationary and your eye travels down in a vertical panel to see the cicada.

There's a lot of intuitive things that hopefully happen. Part of the reason why I started teaching many, many years ago was because there are so many moving parts to comics. I knew I needed to remind myself of what they were. So, talking about them to a group of people, I'd be exploring the form. While I was studying up in order to talk about comics to a class, I’d find myself looking into early comic strips, so I have some of those page designs imprinted in my memory. I might recall some comic from a 1905 newspaper where somebody did storytelling using vertical panels and that comes back to me when I'm considering what page design works best for my story.

There's also the question of moving from page to page: “How do I keep it interesting, connecting one page to the next?” Seeing where an important moment lands and have the surprise be on a page-turn. I also think about how can I change things up so it doesn’t become visually monotonous. In the case of Insectopolis, there was a point where I was doing Alexander von Humboldt’s biography; I was doing panel after panel and was getting bored with the consistency, so I decided to make that spread into a giant image of his head and the panels are inset. This changed the layout into a more flowing narrative.

Yet you don't want to do too much of that fancy footwork or it gets distracting. I don't like that when I look at comics. I don't want to have it be splash page after page. So, it’s looking for a balance between those visuals to keep it lively, but not doing it just for change’s sake. Another example was the rough sketch for the biography of Margaret Collins, who studied termites, but was also a civil rights activist. I sketched the shape of the termite mound and looking at that mound shape I realized the top looked like it could be a KKK hood – which was appropriate to express an aspect of her challenging history and informed the page design.

I’m also interested in how you radically remove the reader from the human perspective in your work. In Ruins and Insectopolis, for example, the reader shares the monarch's perspective for a portion of the narrative through DNA, cardinal directions, UV light, and the Earth’s magnetism. How do you think about constructing these kinds of radically different, non-human perspectives in a visual narrative?

I think one of my fascinations with insects is the alien aspect of them on one count and then having empathy – seeing their complicated process, raising monarch butterflies in Mexico, and witnessing their struggles to reach adulthood. I couldn’t help but wonder, “What are they thinking?” All of this exploration got me looking into the monarch’s journey. Entomologists still don't know exactly how monarchs know to make their way from Canada to this one forest in Mexico over 3000 miles, flying 50 miles a day. So, how do I express to a reader what's going on in a butterfly’s brain? I've now entered [the monarch’s] world and I'm [visualizing their journey]. This is a good example of the stumble-upon I mentioned earlier.

I was on the subway, drawing in my sketchbook while the train is shaking around. I just put a couple of panels down, then started doodling out some lines. One scratch made a circle, then I started crosshatching it. Every day, I would do a little bit more, adding another panel and putting in action lines. I place different panel shapes playing off the circle like it was a sun and these are rays. Because I was so immersed in working on Insectopolis, everything fed into that. I looked at the developing sketch and thought, “Oh, what if this is inside the mind of the monarch?” I did multiple panels before I had any notion that this was going to be a spread in Insectopolis.

That’s really interesting. You're moving through space and vibrating through space to a destination, while you're constructing a monarch journey vibrating through space and moving towards a destination. I think there's something incredibly meta about that, which is great. It’s like you’re embodying that feeling and the sensation almost unconsciously.

Well, to connect that to The System, that [book] totally came out of one of those moments. I would get on the last subway car each day and I’d be looking at the crowd getting off and then getting back on the same downtown train some hours later. It started to seem like a cast of characters that would be a good setup for a play. That [idea] went into a little folder that I threw things into for eight years. An article about a subway driver that was drunk and crashed a train, that goes in there. There was a racial attack at Howard Beach, that goes in the file because somehow it tangentially relates. There was a homeless guy I saw regularly in my neighborhood and he went into the story. These interactions just kept on going and going. It was about recognizing information that was coming at me all the time and finding the ways it all could connect.

A big thing I talk about in teaching is the importance of capturing ideas or a passing thought, which is essential for doing New Yorker cartoons. If an idea comes to me during a conversation at dinner, if I don't write down right then, I lose it. So, I carry this [notebook] with me at all times. It’s all little notes (shows page): There's Jesus coming to a Jesus moment. I probably have 50 of these books over the years. A lot of my Charlie Hebdo cartoon ideas are in here.

I had the idea for Sticks and Stones in a movie theater while watching a documentary on an artist named Andy Goldsworthy called Rivers and Tides. In the documentary, he mentioned he was looking at a mountain and he suddenly had vertigo, realizing that [the mountain] hadn't always been there, it moved hundreds of miles over millennia. In the theater, I wrote down: Rock forms. Becomes king. Empire rises. I went scribble-scribble, put [the notebook] in my back pocket, and forgot about it 100%. Three months later, I was between jobs and was flipping through my notebook when I came upon that 1. That note turned into a 128-page graphic novel I spent a year on and was published by Random House. That’s why I have the fear of losing ideas! I recommend keeping a notebook and pen handy at all times.

Drawing regularly or working on projects is just like exercising, if you don't do it much you get out of shape or if you start and stop it's horrible for the project. I find it very difficult coming back after a break from a project and getting in the frame of mind of the story. When I am in the frame of mind and that's what I’m primarily doing, then I'm having dreams about it and waking up in the morning with something that I might do that day – getting on a track like that is ideal. Regardless of whether I have a big project or not, I try to draw daily and keep my hand in motion, so that when I get up in the morning, I will be raring to go.

Keeping that drawing wheel spinning is really important. When I travel, I keep my sketchbook going and will often dedicate quite a bit of energy to it. I draw some from life, a statue, a tapestry, a dog on the street, from a photo I took etc. I mix and match, keeping that muscle alive. I use photos to get all the details right for something like Insectopolis, like all that architecture and the specifics of the insects. But, I also have to make sure that I draw from my imagination, because those are different muscles.

I want to ask you about symbolic spaces in your work. It seems that you are often using windows and doorways and other liminal spaces like subway cars as frames. Can you tell us more about using these thematic frames in your work?

Travel has been a huge part of my inspiration, and it's where I have always done a lot of my sketchbook work. Because of my father’s sabbatical, our family was traveling and camping through Europe on our way to Israel. So, I did a good amount of traveling at a young age.

When I started traveling on my own, which was as soon as I could, you're looking at maps a lot, especially in the late ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, You didn't have Google Maps, so I had physical maps and I began collaging them into my drawings. I started to see the faces in maps and play around with that too. I’m sure LSD probably figured into my tendency to see things morphing, like screaming faces in wood paneling. I came back from one of these road trips and I had in my mind that I was going to incorporate maps into my work. So, like every job I was working a map into as part of my style. It was too short of a leash. I couldn't do that every time, but for a while I tried!

I was collaging other things too. Stamps photos of hands and eyes, colored paper, which had more longevity in my work. I think collage came into my work as a way of visually responding to how the world was changing new things overlayed on the old. The world started to seem like a collage – just the way our brain is taking in what's going on. I think at that point in the 1980s, life seemed very much like a collage of events. Even when you look at the world, you're walking down the street and you're seeing the art on the lampposts, signage, a person coming towards you, the car going that way, a siren going by. There're all these sensory things coming at us all the time and there're different ways you can demonstrate that through art.

It was also coming out of the scrapbooking that that my family did when we were traveling. We were always saving some little map, or some booklet, or a ticket to a show I had that experience. So, my sketchbooks started to be very scrapbook-y that way – saving a map, gluing it in, was a nice representation of the location attached to a memory.

Your work doesn’t just highlight the simultaneity of arts, or spaces, or objects, or events – it also highlights a simultaneity of time. For example, in Insectopolis, you locate the reader in the space the New York Public Library, but you show the layers of time in that space. How do you bring these layers of time into collage with one another?

A lot of that is intuitive after fifty years of drawing, thinking, and teaching about comics. Comics requires expressing the passage of time from panel to panel, deciding how much time passes, in the leap from frame to frame. It’s the job of the artist-writer to help the reader follow that and be clear on what transitions are taking place. Even the action of turning the page, takes time. The artist can make this leap in storytelling from one panel to the next and also create a moment of surprise with a page turn.

With Kafkaesque, I had the anchor of Kafka’s words and so I could do some crazy storytelling where the character in, say, “The Burrow,” is crawling up the page and I’m hoping to get your eye to follow him as you follow the text. In Drawn to New York, I experimented with scratchboard. I drew a foreground figure, then drew a giant head on page, put panels over it, then drew things in the individual panels. I scratched in a way that would make that face background. So, you're seeing the whole page and then you're looking at the individual panels and actions with time going by. What art form can you do that in? That is one of the many incredibly unique things that comics makes possible.

Speaking of time, when I visit the Natural History Museum, I feel like I’m stepping into a time machine. Same with going to a library or an art museum. Getting to stand in front of a Van Gogh painting and realizing that he was standing in front of this canvas is transporting. It's one of the things that makes me feel okay about humanity – we were smart enough to preserved these things. We had the wherewithal to save art treasures, record ideas and knowledge and history, then preserve them in institutions through time.

Sadly, now we are dealing with an administration that is trying to destroy all that by defunding these institutions. They’re trying to eliminate all of this history – especially Black history – that might inform us about the past so we can make educated judgements about the current events. There's a serious danger that people will forget even recent history as the narrative gets expunged and rewritten.

I'm wondering if this kind of continual sense of simultaneity in all of these forms is what might draw your work towards surrealism, and why you're drawn towards including other surrealist creators, like Franz Kafka and Winsor McCay. This intertextuality is a big part of your work, and it's often turn of the twentieth century comics animation, or even German Expressionism. Can you tell me about including surrealism and surrealist creators within your own work and what that's doing?