Ben Juers of Glom Press has an avant-garde Eurocomics column in The Comics Journal, Pointu Vague. For The Comics Journal #311, he wrote about Isidore Isou’s Journals of the Gods, Gabriel Pomerand’s Saint Ghetto of the Loans and Roberto Altmann’s Geste Hypergraphique. In this excerpt, he discusses Lettrist and Situationist comics and the theory behind them.

In a previous column, I mentioned the difficulty of tracking down three important-but-overlooked, experimental comics-y works: Les Journaux des Dieux/Journals of the Gods (1950) by Isidore Isou, Saint Ghetto of the Loans (1950) by Gabriel Pomerand and Geste Hypergraphique (1968) by Roberto Altmann.

Each of these artists were Lettrists, a movement founded in Paris in the 1950s by Isou and Pomerand. Until recently, Lettrists were known mostly as precursors to the more famous Situationists. But the former kept churning out cutting-edge nonsense long after the latter’s influence catalyzed in the May ’68 Paris riots. (The Situationists didn’t instigate the riots, but their slogans were everywhere; they were “in the air,” as Murray Bookchin put it.) An Isou biography by Andrew Hussey, along with Frédéric Acquaviva’s mouth-watering catalog of their print works, Lettrist Corpus, both published in 2021, have raised Lettrism’s profile. On the back of this, World Poetry Books have just reissued Saint Ghetto of the Loans. Perhaps Journals of the Gods isn’t far behind. In the meantime, I’ve tracked down secondhand copies of Geste Hypergraphique and Isou’s elegantly named Initiation to High Voluptuousness (1960), which, along with Isou, or the Mechanics of Women and I Will Teach You Love, make up his “erotology” trilogy. (He wrote porny novels for a living.)

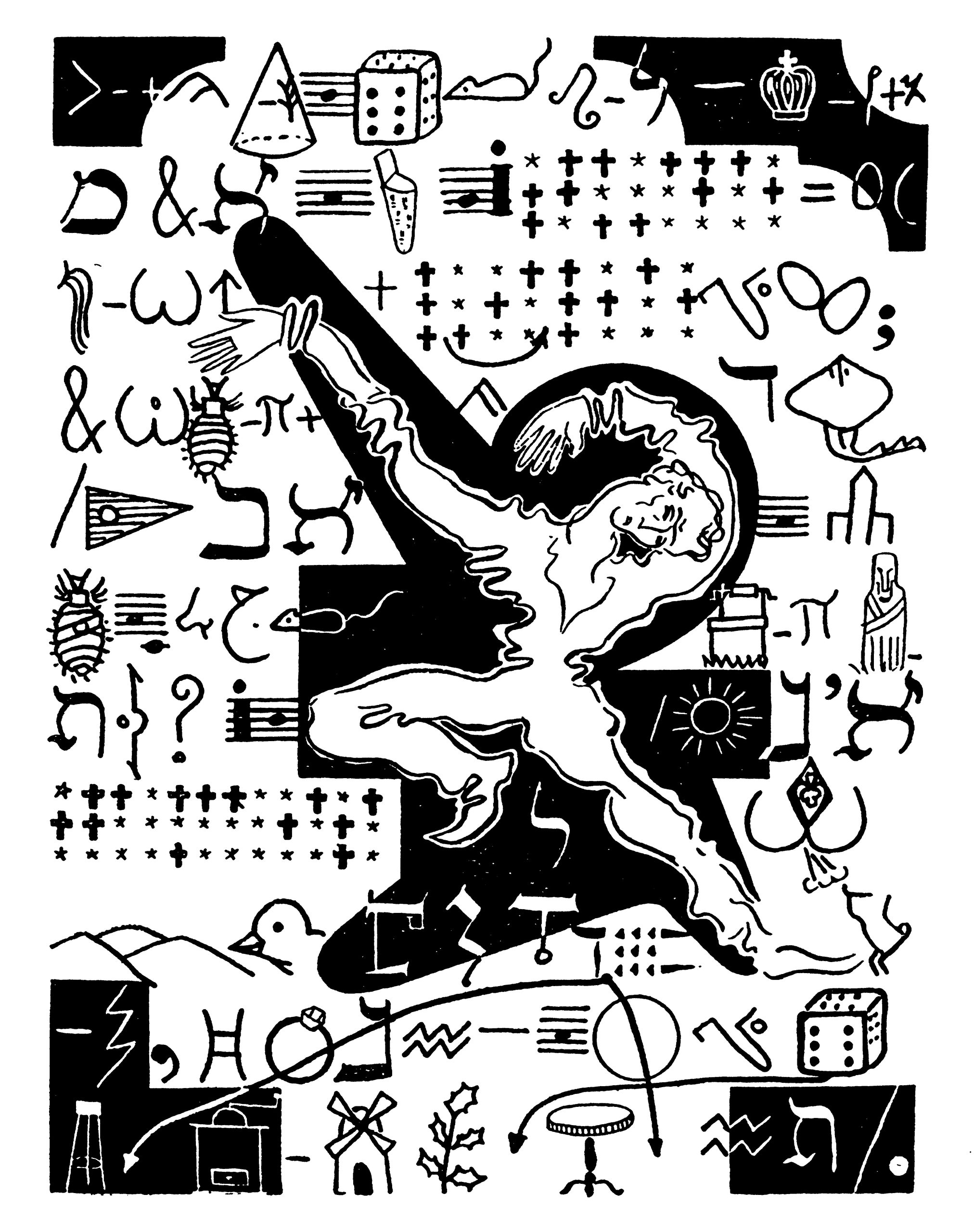

The Lettrists’ main technique was what they called hypergraphy. At first glance, hypergraphy looks like unhinged wingdings, Sumerian cuneiforms, first gen Mac clipart, a prison tattooist’s flash page, hobo signs, Martian script from a 1950s sci-fi or an eye test devised by a deranged optometrist. Its scrawled, hodge-podge imagery includes — but isn’t limited to — typography, hieroglyphs, musical notation, religious symbols, advertising, real and imaginary alphabets and straight-up gibberish. Like most avant-gardes, it appears both primitive and futuristic, which is how the Lettrists saw themselves: flippantly, they claimed they’d been plagiarized, preemptively, by earlier movements like Dada and Futurism. (It’s difficult to confirm or refute this.) In any case, they soon found themselves plagiarized in a more contemporary way by Guy Debord, whom Isou had purged from the Lettrists. Debord went on to form and habitually purge his own group, the Situationists. Building on the Lettrists’ penchant for vandalism and huliganism (a term from Isou’s native Romania), Debord contrived the French-er détournement. Basically, détournement means retooling commodities into anti-capitalist propaganda: for example, by subbing vitriolic, ultra-left screeds into a Little Lulu comic. Comics were, and continue to be, one of détournement’s go-to mediums. One of the Situationists’ most visible works during May ’68 was a sneering, collaged photocomic titled The Return of the Durutti Column, which chewed out, among other things, the French Old Left. Try going to any anarchist book fair nowadays without spotting that zine of Joe Oriolo Felix the Cat strips, cursing out landlords — that’s détournement.

It makes sense that the Lettrists and Situationists would gravitate towards comics, an amoeba-medium with a bad case of synesthesia, stuck forever at the beginning and end of its evolution, uniquely partial to readers’ subjectivity and to being inelegantly detourned. The difference between the two groups’ relationship with comics is broadly like how the Hairy Who and Pop Art engaged with the medium: one intimately and reciprocally (Isou, Pomerand and Altmann were great scribblers, and actually drew comics themselves), the other at arm’s length and somewhat contemptuously (like Roy Lichtenstein, the Situationists saw comics as something to be caught and tamed).

The semi-cogent theory behind Lettrist hypergraphy is that all forms of human communication undergo an “amplic” (swelling) and “chiseling” (subsiding) phase. Most Lettrist works are chiselers. They tunnel through language, cutting visual / phonetic ties, leaving mounds of signifiers and signifieds. Though nonsensical, the image-text combos left in this wake, with all their potential meanings, speak to countless alternate realities. They therefore augur the utopian amplic phase — I think. Anyway, this all gives Lettrist artefacts a potent, vibrating aura, reflected in their value as collectibles: scuffed first editions of Maurice Lemaître’s UR magazine fetch 3,000+ euros on French eBay. Even freshly reissued, Pomerand’s Saint Ghetto resembles a priceless old, illuminated manuscript — albeit the smutty kind that a fevered monk might’ve found in a dank corner of his monastery’s library and hid secretly under his bed.

Isou’s Initiation to High Voluptuousness is what that same monk might produce if, later that night, he’d gone to bed stonked on mead and bad medieval bread, raved in tongues, hallucinated the hornier Old Testament scenes, and the next morning, tried his hand at transcribing his visions with wellmeant but limited drawing skills. This isn’t to say that Isou can’t draw as well as Pomerand, but his brashness and leeriness make for loopier, heta-uma results — almost as if he’d somehow, preemptively, plagiarized King Terry.

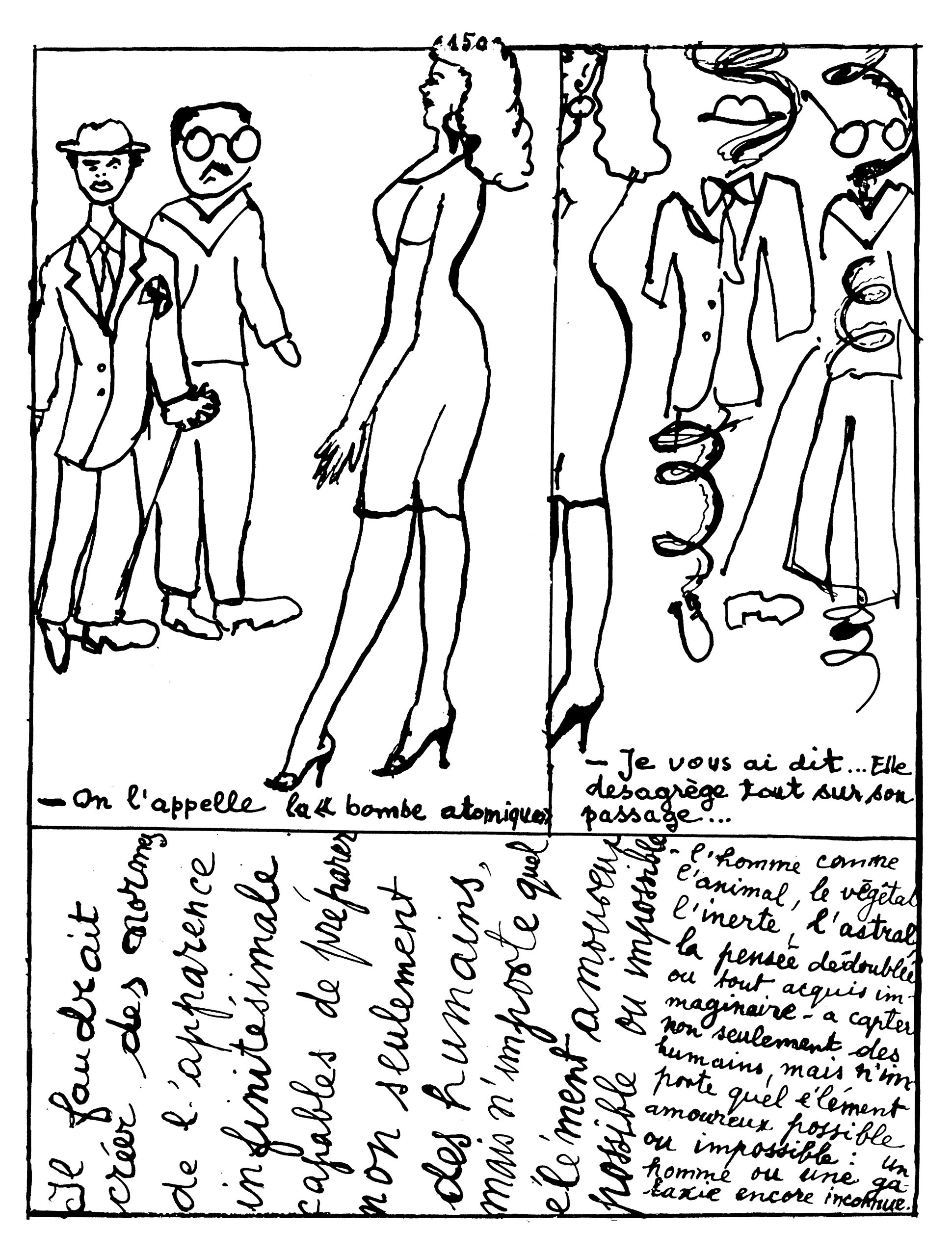

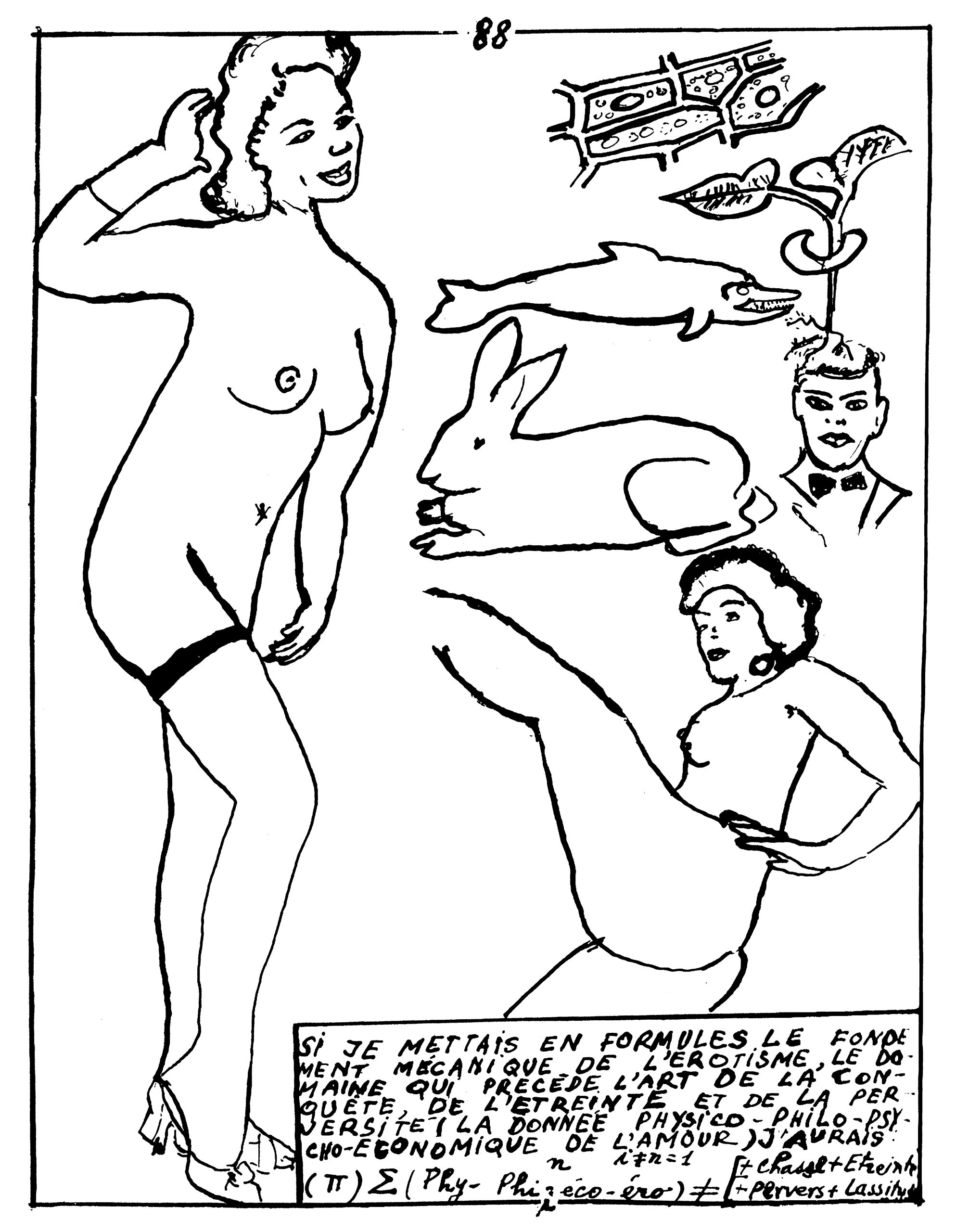

The book alternates between hefty prose and comics sections. The prose imagines numerous day-to-day scenes that turn unexpectedly erotic. The comics pair lurid, scratchy drawings of naked women with graphs, golden ratio-ish diagrams measuring the voluptuousness of women against that of, say, an umbrella or a hammer, and dense, handwritten, metaphysical jargon. Here and there are bouts of hypergraphic babble: sign language, bugles, vegetables, royal crests, pictograms, etc. By the standards of what you might expect from an illustrated treatise on erotics drawn in the ’60s by a French Romanian loose unit, it’s about as misogynist as you’d guess, but in terms of how graphic the imagery gets, it’s actually rather tame, sometimes even sweet, partly because the drawings are too screwy to be arousing.

My trusty translator lens app, without which this column wouldn’t be possible, had real trouble with Isou’s handwriting in the comics bits. Whether this is because Isou’s handwriting is unreadable, or because what he’d written was insane or because my phone was experiencing its own initiation to high voluptuousness, is unclear. Regardless, I’m not sure I’d emerge much the wiser from successfully translating the rantings surrounding a drawing of a woman with a snake’s head, introducing herself to a trio of communists as “a specimen of lustful viper, comrades.”

Saint Ghetto pays tribute to the shady doings, bohemian climate and dilapidated beauty of Saint- Germain-des-Prés, the Paris neighborhood favored by the Lettrists, Surrealists and other weirdos. It varies more rhythmically between text and image than Isou’s book, with Pomerand’s poetry and drawings appearing on facing pages throughout. The poetry is so-so, though a lot of punning, phonetic back-and-forth with the drawings probably gets lost in translation. As with most abstract comics, the buffet of imagery available to Pomerand only emphasizes his self-imposed limits. The rigor he imposes on hypergraphy pairs nicely with the scampy litheness in his line-work. Overall, he’s a more precise draftsman than Isou, though they share many of the same visual tropes: rats, lice, musical notes, bones, stingrays, logos, dice, numerals, crosses, palm trees, sign language, ducks, dicks, tits and asses — lots of asses.

The post Pointu Vague: ‘A Great Big De-Braining Device’ by Ben Juers— The Comics Journal #311 Preview appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment