I recently learned that people talking about manga have a very different definition of “slice of life” than people talking about American comics. In American comics, slice of life refers to work that is realistic, low-stakes, mundane, often seeming semi-autobiographical due to its basis in observed existence. When manga readers use the term, the work they’re addressing might be based in the stuff of daily life, but could also be completely fantastical in the world it depicts, as long as the stakes seem somewhat low, if the structure feels more anecdotal than epic. The “slice” is emphasized over the “life” aspect, basically. This distinction suggests both the broader variety of work represented within the manga industry, and how much less noncommercial manga exists in Japan due to the dominance of that industry and its ability to absorb talented practitioners.

Natsujikei Miyazaki’s And The Strange And Funky Happenings One Day is a short story collection. All of the stories are eight pages long, except for one four-pager, and a two-page story spread across the front and back covers, beneath the book jacket. All are titled with the same grammatical structure as the book title, beginning with “and,” usually followed by a “the,” and ending with “one day.” Each individually feels quite slight, and they do not accumulate to achieve a deeper effect. Still, it is easy to imagine any of these stories, taken on their own, being a favorite piece in the anthology in which they would have run. Perhaps owing to the scope of the span of time each title refers, I have seen them described as slice-of-life. While Glacier Bay largely focuses on translating Japanese small-press work, sometimes giving a book a larger print run in English than it received in Japan, Natsujikei Miyazaki is an artist whose work appears in Hayakawa’s S-F magazine. The Glacier Bay website describes these stories as sci-fi; I would not. They are absurdist, but in their capriciousness, like that of childhood subject to the whims of adults, it often feels more melancholy than plainly humorous. That is not to suggest that this feeling, of life’s ridiculousness beyond our power, goes away as you age. Rather, depicting the arbitrary nature of fate in adulthood would scan as cruelty, rather than the wondrous tone saturating Miyazaki's stories.

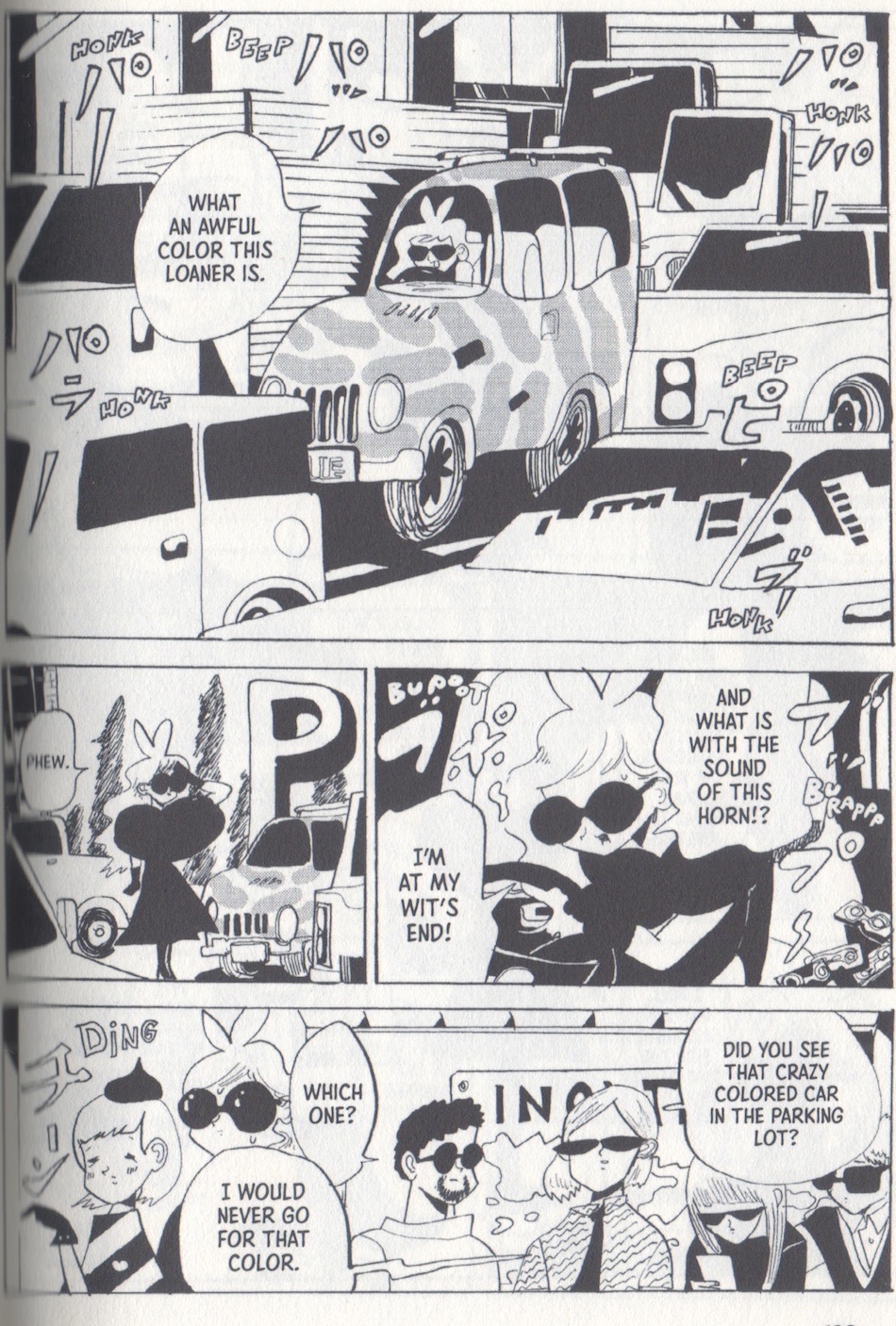

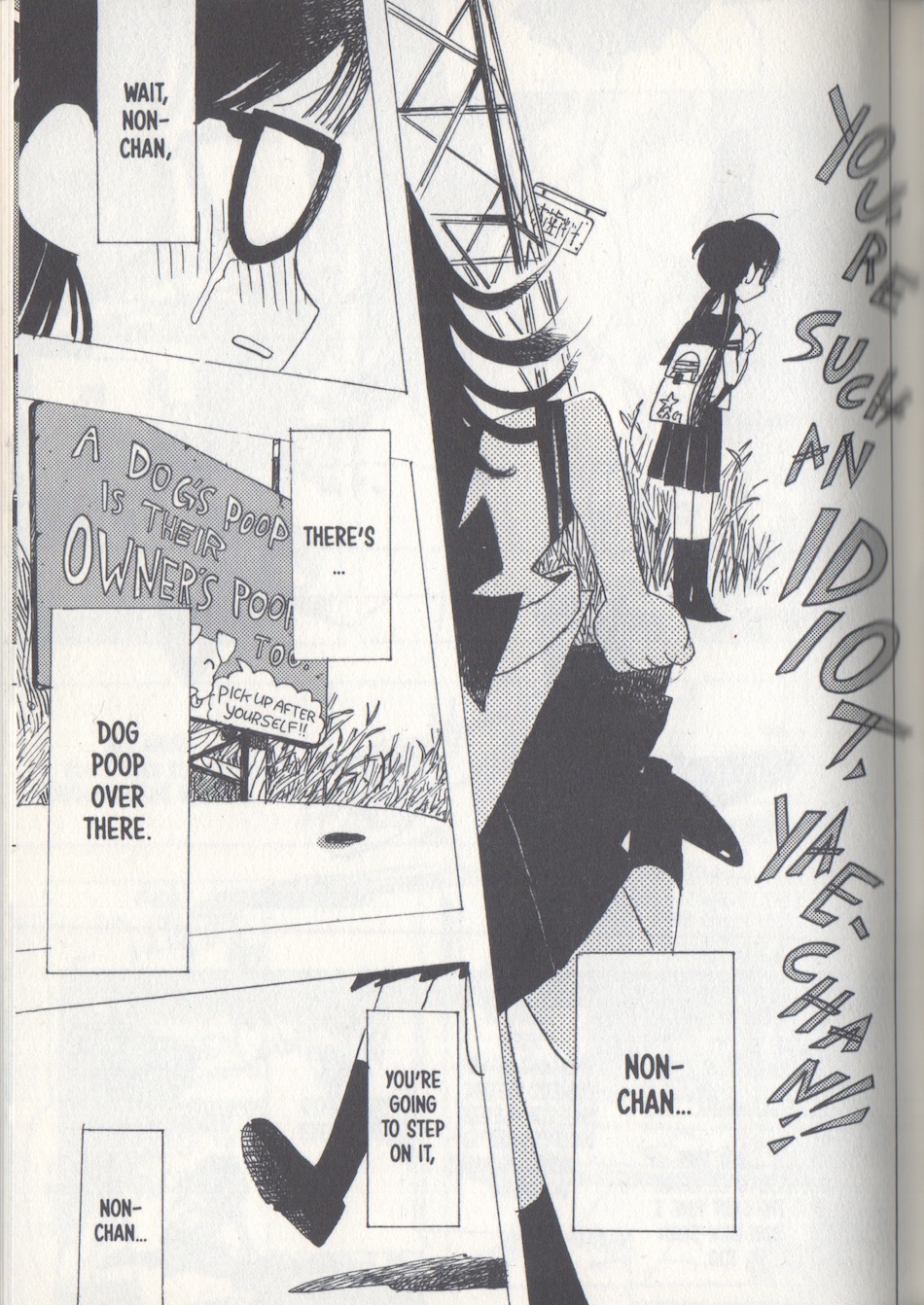

These stories are not mean, although I suspect the addition of such a mode to their register would expand the book’s range and improve it overall. A dash of Yoshikazu Ebisu never spoiled any broth! The stories lack a certain punchiness, despite their brevity. The cadence to the stories has very little happening within a single page, with each idea finding a conclusion at the end of a story. Each page unto itself feels decided more by the balance of visual elements for the sake of overall composition than as a way to convey a narrative idea. To excerpt a page feels like I am showing you not a full sentence, but a beautifully wrought clause, that may lack either subject or object. One page may be a setup for a joke, with the punchline delivered after a page turn, for maximum surprise, because the jokes are visual, not verbal. Both this book and Imai Arata’s Flash Point feature page turns before the punchline of an annoying guy getting jump kicked in the face by a schoolgirl. In the interview with Arata included in Flash Point’s Glacier Bay edition, Arata cites Miyazaki’s manga as featuring pretty much everything he likes to see in a manga, aside from political content.

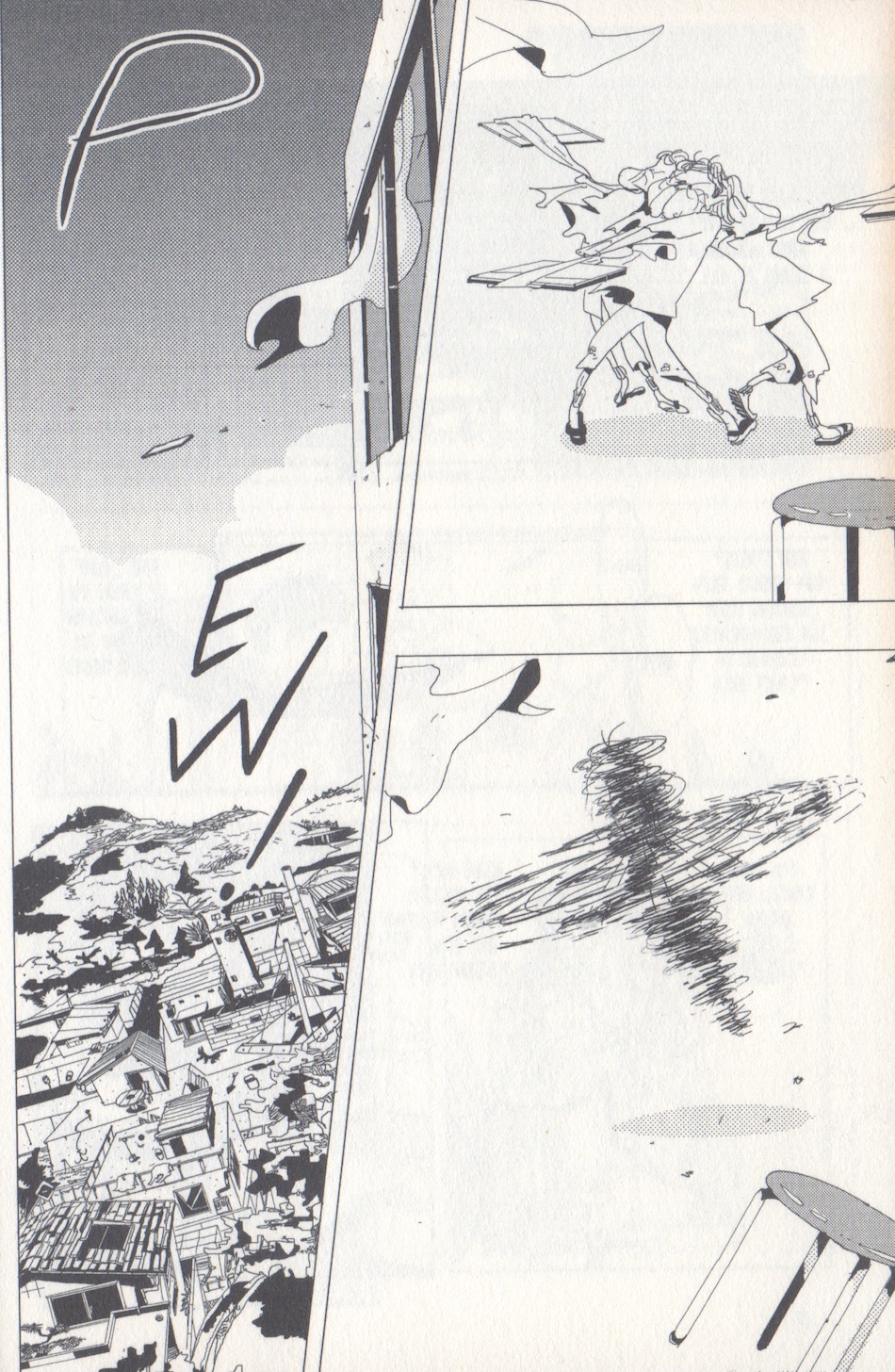

Miyazaki’s drawing is fun, with an appealing sense of composition and design. Backgrounds are antic, while characters are designed with a sense of open space to them, resembling an idea of manga designs as big eyed neoteny built out of bubblegum, but with a sense of sharp points to it that aligns with the background's sense of being crammed with askew angles. Detailed backgrounds and simplified characters follow a tradition of basic cartooning design principles, and yet here those choices are isolated from each other, to be employed to different ends. Characters are emphasized in panels and pages that are fairly open, with camera pointed skyward, while the more antic and cacophonous panels often emphasize backgrounds to the point where characters are diminished inside them. Angles are chosen to keep this tension in place as the story moves — the characters isolated and alienated from the noise of modernity, rather than applying an animation-ready distinction between foreground and background that nonetheless accumulates into a holistic design sensibility. Characters occasionally lose their shit, working themselves into a fury wherein they lose track of their own design to instead exist in a whirl of motion, of a piece with the background noise.

While the design sensibility is clearly that of manga, there are traces of visual influence from a broader world tradition of children's books, reminiscent of Tsuchika Nishimura, who recently came to U.S. shores with the two-volume series The Concierge At Hokkyoku Department Store. There is a sense of humor similar to that I see in Keigo Shinzo’s Tokyo Alien Bros, recently serialized by Viz. Any point of comparison should be taken with the understanding that my knowledge of manga is incredibly limited, in that I am completely unaware of the most popular works, which are presumably the most likely to have widespread influence. However, I have also seen all three of these artists cited as favorites of the new generation of mangaka by Taiyo Matsumoto, who is similarly a fan of, and influenced by Fumiko Takano, whose book Miss Ruki was published by NYRC this summer; one can see the Takano influence in Nishimura and Murakami’s work, while the Miss Ruki translation is hyped up with a quote from Shinzo. These are figures it might make sense to consider existing within the same continuity of aesthetic tradition. They are well-drawn and designed. and the overall effect they conjure, to varying degrees, is a charming one, enough to overcome the suspicions of those generally wary of cuteness.

Miyazaki’s work shares with Keigo Shinzo’s a sort of dumb guy amiability, the sense that to overthink things only leads to suffering. Shinzo imbues his characters with this perspective, but Miyazaki embeds it into the story structures themselves. A story might stir up ideas or mysteries, then offer as explanation a sort of non-sequitur. Take the story where a dog appears outside the window of a school, and over the course of a few panels many of the students think it might be their pet, come to visit them. The explanation is that it is a mass produced toy that was at one point incredibly popular, and this one in particular is one that has become possessed by a demon, and then receives an exorcism, with everyone then saying, ah, I guess it wasn’t any of ours. Both artists say “Don’t take this too seriously” in a way that is both refreshing in the context of how art is usually presented and frustrating in large doses.

The book itself constitutes a large dose; bring a bookmark. (Also, the paper is abnormally thick; I consistently found myself turning a page and hesitating with the thought that I might be turning two pages at once.) There are a pair of stories presented back to back, where something happening in the background of the first story is foregrounded in the second, that suggests there might be greater connections to be found throughout the book if one is paying close attention, but it is only those two stories that play such a trick. I would advise you read at a pace of one to three stories from this book per day. Otherwise, you might begin to feel like the character in “And the Lifetime Supply Of Pizza One Day,” who, having won a contest, is not able to turn down a pizza without incurring a fine. Ingredients may vary, but the constancy of the form overwhelms.

As a photorealistic drawing insists you respect the level of craft that went into it, so too does a more realistic narrative insist you take it seriously through its resemblance to life as lived. One can affect a take-it-easy nature all you want, but real life remains serious for its being literally all we have. Realism as a form can achieve a certain kind of transcendence by recapitulating and reframing all that it is easy to take for granted. The type of “slice of life” you get in Miyazaki, despite its charm, feels merely cute. Cuteness can be a difficult bar to clear, but it is still a goal which doubles as a dismissal. Miyazaki’s work is broadly appealing, on a commercial level, for its basic friendliness and approachability. It feels averse to the real, which includes pain and suffering, general discomfort. Instead, the undertone is one of gentle nostalgia.

Taiyo Matsumoto, whose work I adore, was quoted as saying “American comics are powerful and cool. European comics seem very intellectual. And Japanese comics are very light-hearted. If you could combine the best of all three, you could create some really tremendous work. That’s my goal.” I am surely not the only person who has wondered what American comics he would have seen and considered cool, or if it’s Crepax he thinks is intellectual, or what. However, Natsujikei Miyazaki’s work does seem genuinely light-hearted in a way I appreciate, even as I felt, while reading it, increasingly aware of the dimensions it lacked that would need to be present for me to feel it was really tremendous.

The post And The Strange And Funky Happenings One Day appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment