Most mainstream manga are labeled according to the demographic of the magazine in which they’re serialized: shonen (boys), shojo (girls), seinen (men), and josei (women). But those tidy-looking sales categories have always slopped over into each other, and they don’t necessarily fit Western assumptions about age and gender. Shojo artist Keiko Takemiya, who drew the first Boys’ Love manga, also drew science fiction manga for shonen magazines. Many of the great horror manga artists, like Kazuo Umezz and Junji Ito, got their start in shojo magazines, which used to be the places to go for horror. (Ito’s breakout hit Tomie ran in the shojo magazine Monthly Halloween, which periodically goes viral on social media for its magnificently ’80s photo covers.) American newcomers to manga are frequently surprised that romantic comedy is a major genre in boys’ manga, and that women-drawn romcoms like Ranma ½ and Chobits are shonen manga aimed at teenage boys.

In recent years, seinen has become perhaps the most fluid of the big four categories. Once upon a time, seinen manga were stereotyped as comics for salarymen to read on the subway on the way to work. They were Tom Clancy-style thrillers like Kaiji Kawaguchi’s naval manga The Silent Service and Zipang; or cheesecake like Kosuke Fujishima’s Oh My Goddess and You’re Under Arrest; or macho fantasies like the always-popular ninja and samurai manga; or infotainment like the incredibly long-running Cooking Papa, by Tochi Ueyama, which includes recipes. Or they could be all these things at once, like the ultimate salaryman manga, Kenshi Hirokane’s Kosaku Shima saga, about an executive who rises through the ranks while learning the secrets of corporate success and bedding beautiful women who can’t get enough business dick. The manga’s title changes every time Kosaku Shima gets a promotion; it’s currently Outside Director Kosaku Shima and will hopefully last long enough for Shima to merge with a mass of sandworm larvae and become God Emperor Kosaku Shima of Dune.

But it’s been a long time since Japan was a bubble-economy culture driven by necktied men with no time for dreams more complex than sex, power, and well-prepared food. Modern young men have more varied and playful fantasies. (And seinen manga has always had its lighter side; Makoto Kobayashi’s cute 1980s cat comic What’s Michael? ran in the seinen magazine Morning, as did Kenji Tsuruta’s sweet steampunk series Spirit of Wonder, one of the prototypes of cozy “healing” manga.) Maybe today’s seinen magazines are picking up work that in earlier eras might have wound up in alternative or gekiga magazines, fewer of which survive today. It may help the quality of adult manga that they’re often on slower schedules than weekly kids’ manga, giving the artists more time to write and draw. Whatever the factors, a lot of seinen manga magazines have become less “manga for men” and more “manga that’s too good for the kids’ magazines.”

Which is, maybe, how you get Kamome Shirahama’s Witch Hat Atelier, which has the plot structure of a Shonen Jump manga, the art of a particularly lovely Victorian children’s book, a core cast of spunky tween girls, and a premise that might be summed up as “What if Harry Potter was much better?”...and runs in the Morning spinoff Morning Two. Other Morning Two titles include Saint Young Men, a comedy in which Jesus and Buddha share a Tokyo apartment; Heaven’s Design Team, which teaches evolutionary theory through the work of product designers creating animals to God’s client specs; and Cells at Work: Lady, the OB-GYN variation of the expansive medical edutainment franchise. If you tell an American publisher that this is what the average man wants to read, they will punch you and then cry.

But it’s all worth it, because Witch Hat Atelier is shaping into one of the great fantasy comics.

“Is an athlete always an athlete, even from birth?” asks the opening page. “What about astronauts? Or pop stars?” Coco, a clothmaker’s daughter growing up in a cottage on the edge of nowhere, has been raised to believe that birth is destiny. Only an elite few are born with magical power and can become witches, capable of wielding magic and creating enchanted “contraptions” for the mundane populace. Coco fantasizes about becoming a witch but knows her dreams are impossible. She was born normal.

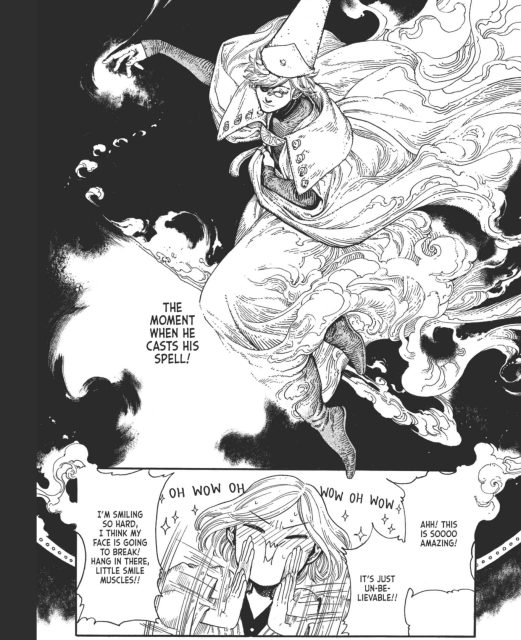

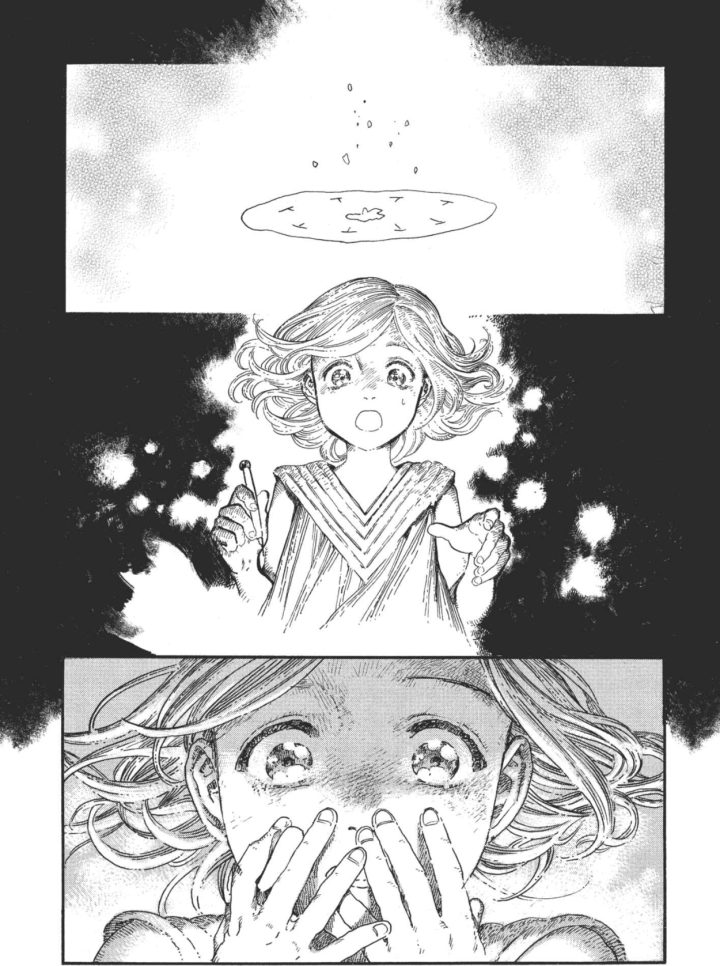

Then, by accident, Coco learns the most closely guarded secret of her world: given the right tools and training, anyone can learn magic. In the past, unrestrained spellcasting led to devastating magical wars and monstrous abominations, so now witchcraft is relegated to carefully chosen apprentices, mostly recruited from established magical families. Coco receives a book of spells from a mysterious witch dressed like one of the cultists from Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, and in time she learns the second big secret: “Magic isn’t cast with words…it’s drawn!” Witches make magic by drawing patterns in enchanted ink, and now Coco knows that, she can do it too.

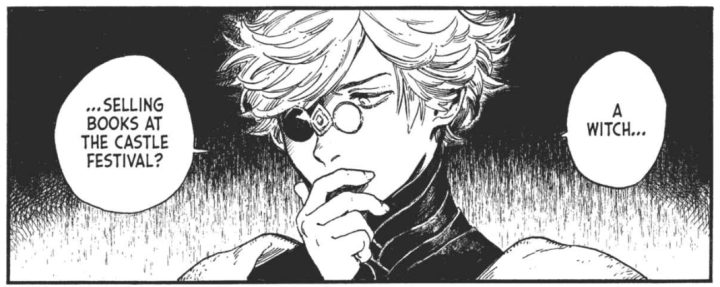

But one of Coco’s spells goes wrong and turns her mother to stone. Just as seriously, it attracts the attention of Qifrey, a bishonen male witch. Witches are supposed to deal with outsiders who stumble on the secrets of magic by erasing their memories, but Qifrey hears Coco’s description of the witch who gave her the spellbook and believes it may be a lead on the Brimmed Caps, a magical rebel group he’s been hunting. So instead of mind-wiping her, he takes her on as an apprentice, inducting her into the world of witchcraft. Premise established!

Qifrey’s atelier, nestled in the countryside, already contains three apprentices, all girls about Coco’s age, as well as rugged Olruggio, Qifrey’s friend and the atelier’s “Watchful Eye.” Perky Tertia and shy, serious-minded Richeh are happy to make friends, but Agott, an arrogant girl determined to excel at spellcasting, sniffs, “There’s nothing to gain in spending time with someone beneath me.” Time for Coco to roll up her sleeves, get some ink on her fingers, and learn everything there is to know about being a witch.

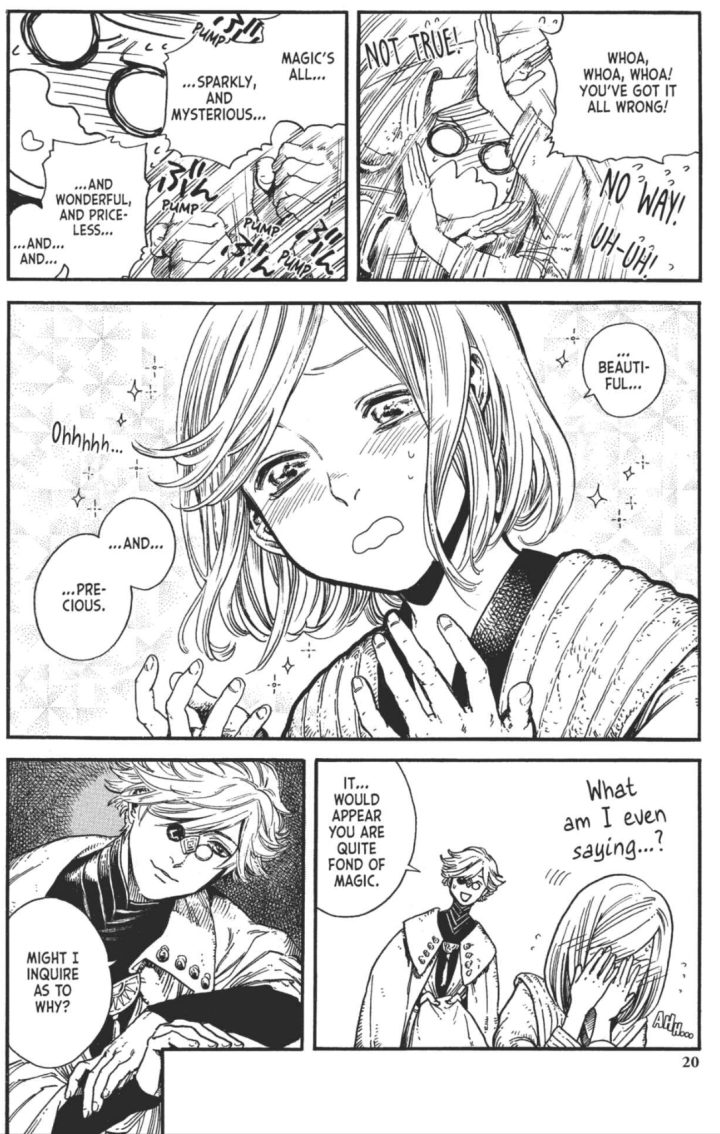

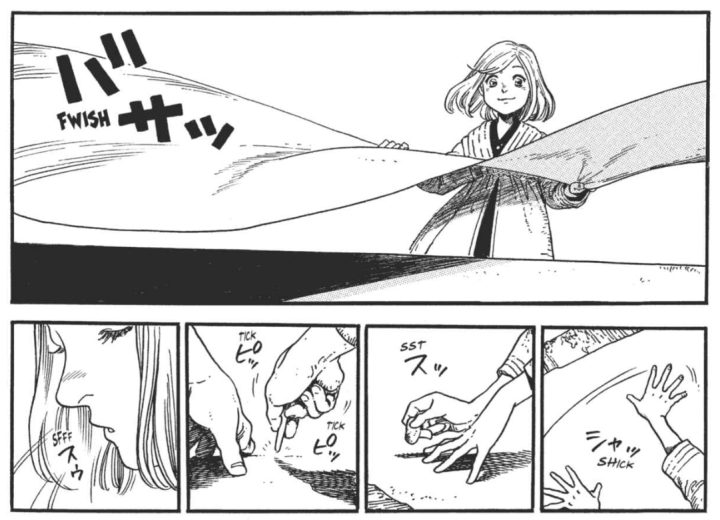

The premise of magic as art, and art as magic, is perfect for a comic book, especially one as enchantingly drawn as Witch Hat Atelier. As in the Hayao Miyazaki film Kiki’s Delivery Service, witchcraft serves as a metaphor for the artistic process, and, like Miyazaki, Shirahama depicts the process with equal parts sense and sensibility. She provides careful drawings of her witches’ tools, materials, and spell diagrams. She devotes much space to the apprentices’ drawing practice, the rules they learn for creating spells, and related crafts like the making of magical ink. “Just because anyone can draw magic doesn’t mean that it’s easy to draw well,” Coco is warned. The apprentices work hard and take pride in their ink-stained hands.

And yet anyone can draw. One of the manga’s core themes is that art belongs to anyone willing to put in the work, that the wall between those who can create and those who can’t is an illusion put up by society. The witches get creative block, get frustrated by their own slow progress, struggle to find spells that fit what they want to express. Agott shows the people-pleasing Coco how to create for herself, and in the process discovers the pleasure of creating for someone else. Riceh worries that too much study will make her lose her own artistic voice: “You start reading, and next someone’s telling you to copy what’s in there.”

Another oft-repeated message is that art has power; there’s a reason society tries to restrict it to a small, trained group of elites. Qifrey impresses on his apprentices the importance of using magic for the greater good. Witches are taught to consider the possible repercussions before making even minor spells and contraptions public: a cold flame could be useful, for example, but what if it causes children to grow up without a healthy fear of ordinary fire? Witches are also obligated to perform acts of public service, like road maintenance, as part of their ongoing contract with the nonmagical world.

As if to demonstrate what’s possible for apprentices who stick with it, Shirahama makes Witch Hat Atelier overflow with visual delights. There are magical contraptions galore: flying carriages and flying shoes, teleportation pennants with designs you can step through, cosmic toilets that send poop into another dimension. There are fantastic beasts: Coco’s fuzzy pet “ brush-buddy” (a bonus story is told from its point of view in a pastiche of the classic Natsume Soseki novel I Am a Cat), enormous dragons, fierce scalewolves, and myrphons, which are half-gryphon, half-penguin. There are exotic lands: a “mountain range” of floating spheres, a cave shaped like a snake’s head that leads to impossibly twisting passages, and the underwater Great Hall of Witches. The spinoff Witch Hat Atelier Kitchen, by Hiromi Sato, expands the worldbuilding to include witching-world foods and recipes (which the reader can make, substituting the fantasy ingredients with mundane equivalents).

The characters are drawn with detail and humanity that make them more compelling than the magic around them. Unlike too many comic-book artists, Shirahama draws a wide range of figures and faces. There are young witches, old witches, fat witches, thin witches, disabled witches, witches of all ethnic backgrounds. Her world feels fully populated, with kingdoms and cultures stretching over the horizon, off the page.

Shirahama’s art mixes elements of Art Nouveau illustration, classic Western children’s books, and Hayao Miyazaki movies. She also shows a fondness for artists of puzzle and illusion, like M.C. Escher; there’s a playfulness in her layouts, as if she wants to keep reminding the reader that they’re enjoying a story. Characters lean against or hang out of panels. Panel frames take the shape of windows, archways, runic circles, even a board game. One chapter begins with a two-page spread of an open book illustrating a story about the origin of magic. Turn the page, and the book-within-a-book transitions into a manga, with the Witch Hat characters stepping out of a panel to enter the Silver Eye fair. The history of witchcraft continues!

So far, so good; all is for the best in this most enchantingly drawn of all possible worlds. If Witch Hat Atelier were a kids’ manga, Shirahama might not probe any deeper into the witching world she’s created. (Or maybe she would; who knows?) But this is an adult manga, or at least a manga drawn with the expectation that adults will read it. As the story progresses, it becomes harder for the reader or the characters to ignore the flaws in witch society. The mind-wiping might be an early clue. The Witches’ Assembly strictly enforces witch conduct and keeps the secrets of magic, while the Knights Moralis, magical police, delete the memories of normies who see things they shouldn’t.

Due to the magical abuses of the past, Coco learns, certain types of spells are forbidden: those that permanently alter the body, the mind, or the land. (Witch government allows itself one big exception by giving the Knights Moralis permission to alter memories.) This leads to an ongoing debate in Witch Hat Atelier on the ethics of magic and medicine, a departure from the “witchcraft=art” extended metaphor.

The post Witch Hat Atelier: The Work of Art appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment