Memories linger, or so I’m told. Misery of Love is about many things, certainly, but memory — memory as a process in time, as a perception, as a practice? That’s the crucial step, it seems to me.

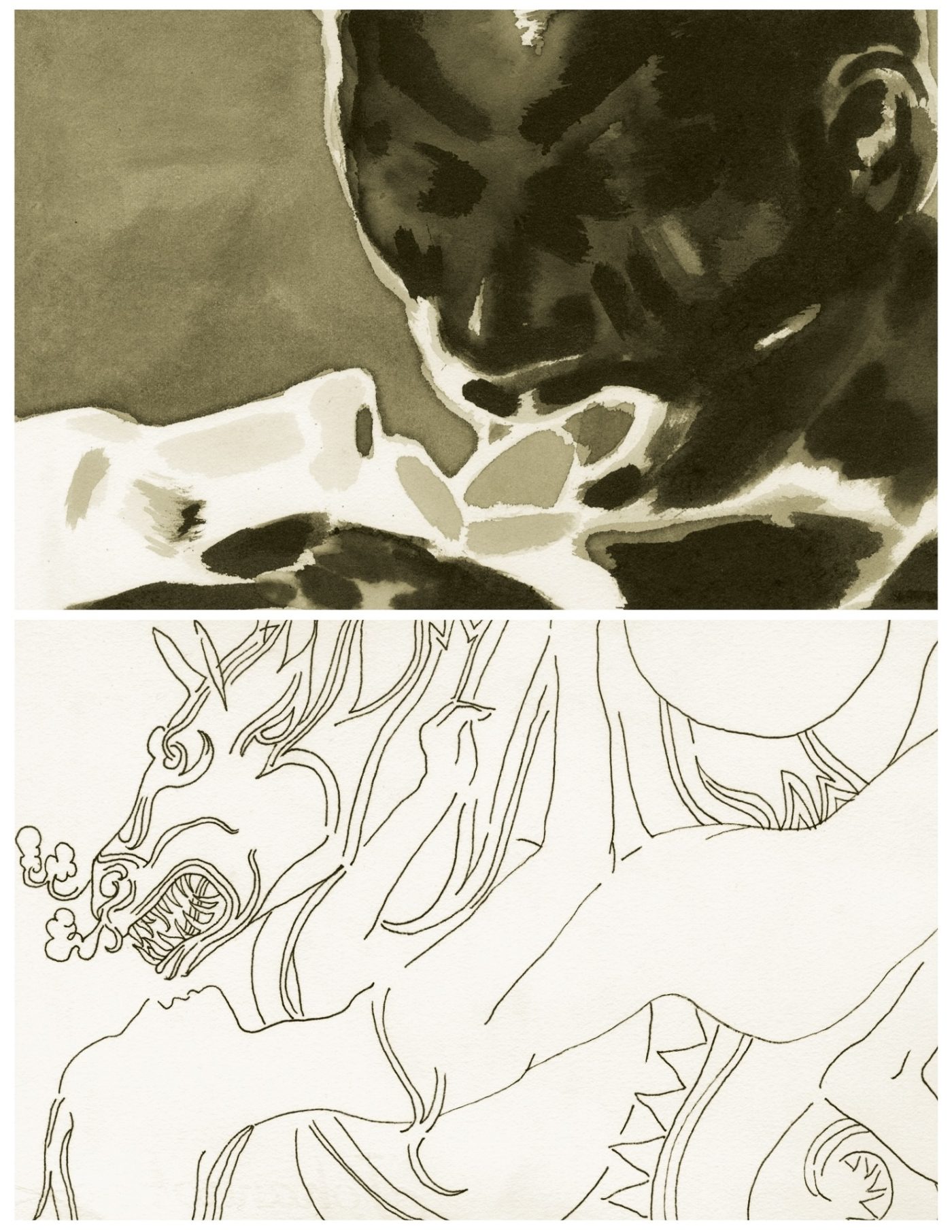

There’s no legend to the territory in advance. The narrative passes in a blear, a series of greyscale images. Uniform rectangles. Two a page for two hundred pages, four hundred images plucked from memory and set in sequence. Filmic in effect. The adjective “widescreen” is usually reserved for action stories, but it seems to fit here because the artist, Yvan Alagbé, is consciously framing his story through a series of static rectangles. (The aspect ratio is 7:5, not 16:9, “close enough for government work,” as they used to say back when we had a government.) It plays out like a movie, but not like anyone on this side of the ocean means when we say that. The explosions aren’t large and well-choreographed. We’re seeing isolated frames of film.

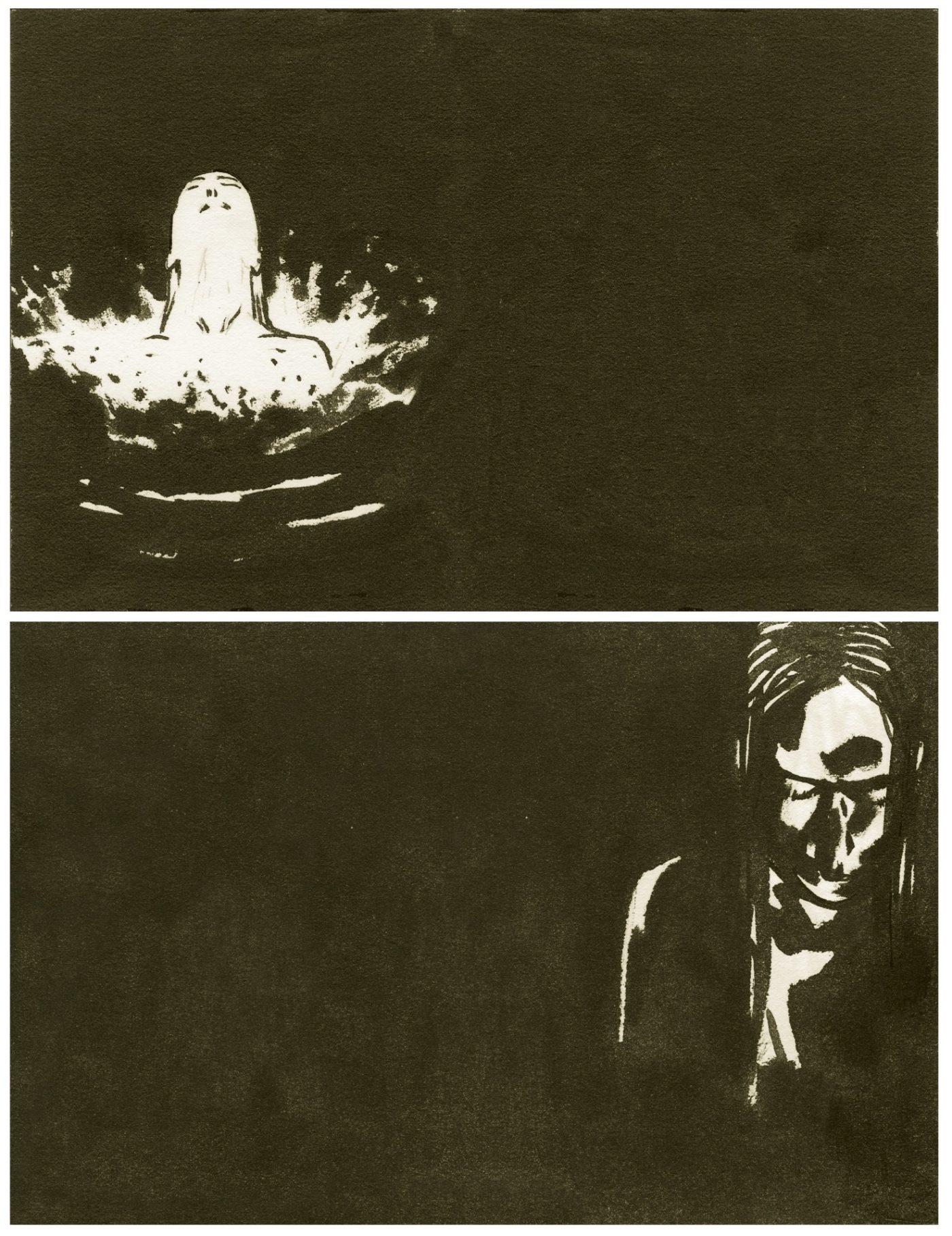

The effect is chilly, unflatteringly intimate and distancing. This is a story of passion and hatred, bigotry coiled like a worm at the core of an unhappy family, spoiling every human interaction it touches. These are dark recollections, racism, estrangement, and lust all caught up together in a ball of painful associations. It demands full and astringent engagement from the reader. Despite moments of hope and occasional flashes of joy, there is no levity.

We are in familiar territory for Alagbé, with characters originally introduced in his previous volume, published in English in 2018 as Yellow Negroes and Other Imaginary Creatures, (released in Europe by Fremok in 2012 as Nègres jaunes et autres créatures imaginaires). Misery of Love is a similarly tardy edition to these shores, arriving 12 years on the heels of its initial publication in French, as École de la misère (Fremok). Better late than never, one supposes.

It’s a story told in shadows, smears of grey. Dream-like, but not as the label is usually applied. Not lyrical or whimsical or outwardly surreal. Are there people who dream in crisp and fully-realized dramatic teleplays? Maybe there are! This looks like how I dream, a grey blur, sometimes disconcertingly lacking definition but indistinguishable from life in the moment. Alagbé is going out of his way to paint with the thick end of the brush. Panels as abstract heat maps.

Sometimes, however, you flip the page and he surprises you with a perfectly realized fine line, like the slash of the whip across your retina. Oh yeah, just a quick little stylistic aside. Very French.

The memories in question, many of them, belong to Claire, who has returned home for her grandparents' funeral. We see snippets of her life, from early childhood through to the present. Formative memories of family, both good and bad. Claire’s memories around the topic of race are painful, shame and embarrassment at open expressions of racism from older male relatives. That in turn becomes — what? A form of rebellion in her choice of lovers? That judgement hovers like a bruise. Many of her memories focus on Alain, her lover, an illegal immigrant who first appeared in Yellow Negroes.

Claire’s family, like every family, is defined by the borders of what can be spoken and what cannot be acknowledged. Racism being, of course, one of those things that certain people can choose not to acknowledge. Some people don’t get to choose that option. There’s a lot of sex here, quite a bit, but it’s not a sexy book. On the contrary, the frequent sexual interludes feel more like intrusive thoughts, a record of — what? Sometimes it involves pleasure, often not. The answer is ambiguous, shameful in recollection if not in fact. We’re not always seeing these people at their best. Sometimes people are at their worst when they’re naked.

I don’t recommend taking your time with the story. Flip through at a quick pace. Let the sequences wash over you, one scene melting into the other, cutting between conversations and random imagery and abstracted motion as montage. Don’t fool yourself into thinking you can make sense of it the first time through. Be shocked, confused, repulsed, without processing. It’s supposed to feel like worrying an old bruise, yellow and swollen. Once you’ve been through, sit for a while before going back. Let it wash over you, lapping at your hem like the waves. It doesn’t let up. Read it again, and again. One of the pleasures of comics is that the reader controls the speed with which we can experience narrative, whereas movies and songs follow involuntary rhythm steady drumbeat like a staccato pulse or a sentence that keeps rattling on without pause comma or period.

So, yes, this is certainly a work of technical virtuosity. Emotional tone forbidding, but cracks of humanity throughout. Parents and children, young and aged — family as a site not solely of strife but of some kindness and warmth as well. The problem is we don’t get to choose which memories carry the most weight. We certainly don’t get to pick our families. The earliest joys are always clouded by later occlusions.

The book is no celebration of misery, quite the contrary. A staccato pulse is still a sign of life, of continuity. People suffer, then they don’t. Children are conceived and born as the previous generation marches off the stage, and that’s the shape of Alagbé’s saga. It all unfolds just like it’s supposed to, whether we wish or no, funerals to fucking to birth all over again.

There’s no euphemism here, for good or ill. No hand holding. The French are the ones who went to Africa in the first place, and its no one’s fault but their own that the imperial project ended only after significant cultural connection and social importation. This makes for the most queasy passages of the narrative, a forensic examination of grandpa’s sexual preferences. Oh, Jesus, you mutter. Of course! Don’t look away here. Lust travels hand in hand with loathing. Where else do you think that hoary imperial instinct comes from? There’s nothing good to find in that tomb.

But a necessary exhumation, yes? It’s so easy to just not say anything at all. To let the secrets molder. Quite easy to just never confront the family. To absolve the dead completely for sins they never requited. So much easier that way. Except in the long run it really isn’t, but no one ever sees the back end of tragedy like that from the outset. Positively Greek in the inevitability of pain revisited upon successive generations.

As I say, despite the stately presentation, this is nevertheless a book to attack and read with vigor. Even as the emotional temperature drops below frigid, and the memory of good sex turns rancid in memory. The well-meaning gestures of emotional tourists appear threadbare, juvenile. Misery of Love encompasses the whole world, and doesn’t give an inch to the reader’s discomfort at any step. A story told in successive detail, often isolated from context. A memory book. Austere and uncomfortable, bracing. Vital.

A hard pill to swallow in 2025, an era defined by organized revolt against the idea of uncertainty in all realms of human endeavor. It got here in good time. Anyway. Now, if it seems like it has a shape in your mind, remember that you read it in a rush. On the second time through you’ll understand it better. It took a while for me to really get at the pith of what the man was doing, but, straight-up: dude got me to sit down and read his book five times in a row, and it’s a pretty heavy ride. He’s gotta be doing something right.

The post Misery of Love appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment