A decade in the making and clocking in at almost 600 pages, The Weight is certainly an apt title for the new book by Melissa Mendes. The author herself has described it as “a heavy project”, and that’s no exaggeration. Beginning with a painful birth, ending in violence, and punctuated throughout by blood, tears, and vomit, it unflinchingly explores the invisible burdens carried by its cast of characters, weaving their story into an intricate tapestry of love and grief, hope and despair, kindness and cruelty.

Although loosely based on a short memoir written by her grandfather, Mendes filters his tale of grinding poverty, hard work, and parental abuse through classic family sagas like East of Eden and The Thorn Birds to create a brutal, deeply moving, but also occasionally uplifting narrative, which is epic in scope but intimate in design. Focusing on three generations of the Hales, a farming family living in rural upstate New York during the middle years of the last century, the book’s main character is Edie, whose cycle of misfortune drives the story. She glowers out from the front cover with unkempt hair, weary eyes, and a deep frown that rarely leaves her face. Radiating equal parts suspicion, contempt, and barely contained rage, it’s fair to say that she does not look happy. Given her background, this is scarcely surprising.

Although loosely based on a short memoir written by her grandfather, Mendes filters his tale of grinding poverty, hard work, and parental abuse through classic family sagas like East of Eden and The Thorn Birds to create a brutal, deeply moving, but also occasionally uplifting narrative, which is epic in scope but intimate in design. Focusing on three generations of the Hales, a farming family living in rural upstate New York during the middle years of the last century, the book’s main character is Edie, whose cycle of misfortune drives the story. She glowers out from the front cover with unkempt hair, weary eyes, and a deep frown that rarely leaves her face. Radiating equal parts suspicion, contempt, and barely contained rage, it’s fair to say that she does not look happy. Given her background, this is scarcely surprising.

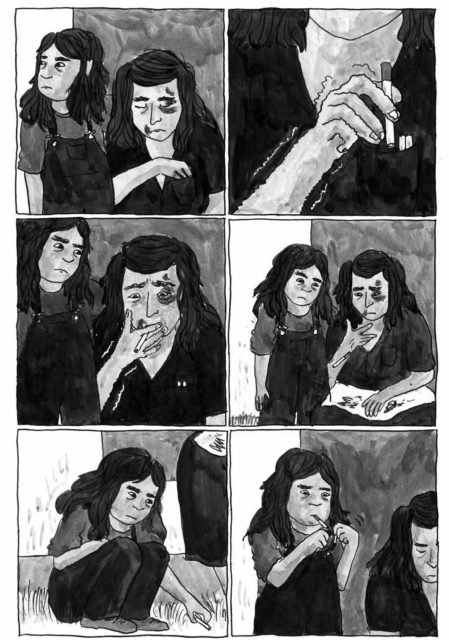

As the story opens, we learn that her mother, Marian, is trapped in a highly dysfunctional marriage with Ray, an abusive and controlling alcoholic who (we are left to assume) only agreed to their union under duress after getting her pregnant. A textbook example of toxic masculinity, albeit avant la lettre, his only purpose in life seems to be spreading pain and misery, perhaps as some kind of revenge for being forced to sacrifice his freedom. Or maybe he’s simply a sociopath. Dead-eyed and expressionless, he barks monosyllabic commands at his young wife, beats her at the drop of a hat, and shepherds her from place to place with a vice-like hand fastened round the back of her neck. Edie, meanwhile, seems to be a nuisance at best, barely registering on his radar except when she tries to intervene in the latest pummelling being dealt out to her mother.

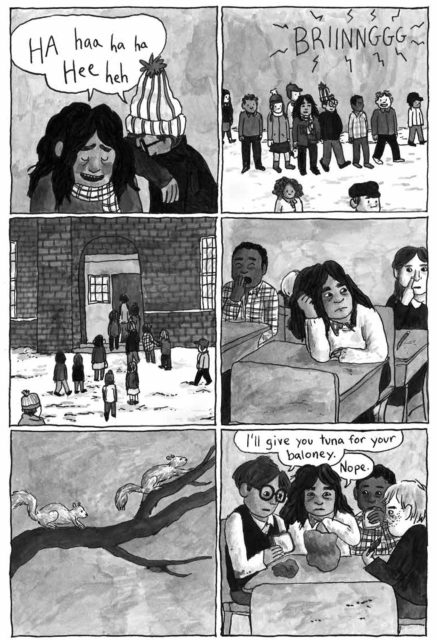

This is a world bound by strict social conventions in which women in particular have little, if any, agency of their own. If you get yourself pregnant, you’re expected to marry whoever did the deed, and damn the consequences, even if it means ending up as little more than a possession. Before Ray whisks his wife and newborn daughter away from the haven of their family home, mere hours after Edie’s birth, he flatly tells her grandfather, “They’re mine now. And there’s nothing you can do about it.” And so it proves. By the time she is at school, Edie has become accustomed to the regular bursts of domestic violence and her inability to do anything about them. Even at this young age, she has learned to internalize her anger, and will spend much of the book punching the side of trailers, scratching the backs of her hands until they bleed, or simply screaming into the void out of sheer frustration.

All this marks a seismic shift from Mendes’ previous books, Freddy Stories (self-published, 2011) and Lou (Alternative Comics, 2016). These early works were much gentler studies of childhood and all its complexities, deftly balancing humor and poignancy with an undercurrent of melancholy that imbued them with real emotional depth. However, while the kids in these books always had one foot in the grown-up world, often privy to things just outside their grasp (depression, divorce, violence), there was never much doubt that things would resolve themselves for the best in the end. They would, in other words, remain children. But that just isn’t where Mendes wants to go here. Like it or not, Edie will be dragged kicking and screaming into adulthood well before her time, and not even the anger and resentment she bears her father will stop her falling into the same trap as Marian, with tragic consequences.

All this marks a seismic shift from Mendes’ previous books, Freddy Stories (self-published, 2011) and Lou (Alternative Comics, 2016). These early works were much gentler studies of childhood and all its complexities, deftly balancing humor and poignancy with an undercurrent of melancholy that imbued them with real emotional depth. However, while the kids in these books always had one foot in the grown-up world, often privy to things just outside their grasp (depression, divorce, violence), there was never much doubt that things would resolve themselves for the best in the end. They would, in other words, remain children. But that just isn’t where Mendes wants to go here. Like it or not, Edie will be dragged kicking and screaming into adulthood well before her time, and not even the anger and resentment she bears her father will stop her falling into the same trap as Marian, with tragic consequences.

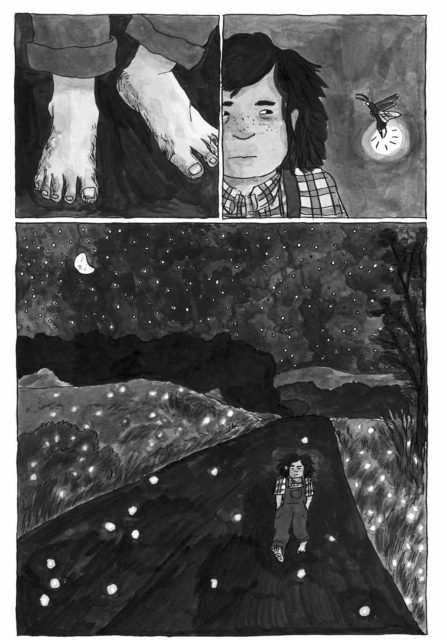

One of the book’s real pleasures is seeing how Mendes’ style has evolved over the past decade. The simple but evocative line drawings of those early books are now embellished with layers of inkwash that bring a richness of depth and texture to the everyday details of mid-century rural America that drip from every page. From empty diners and weatherboard houses to dirt roads and railroad waiting rooms, she clearly has a real affinity for this long-vanished world, which she conjures with enormous care. Similarly, the cast of characters, from the major players to the minor walk-ons, all seem like fully realized individuals, their personalities established by tiny details, from the way they smoke a cigarette or eat a piece of toast to the fabrics they wear and the way they style their hair or make-up.

In many ways, The Weight is the polar opposite of something like Kayla E.’s recently published (and highly acclaimed) Precious Rubbish. Both deal with abuse, albeit of different kinds, but where Kayla’s book was allusive, tightly drawn, and formally complex, Mendes’ work is direct, loosely rendered, and deliberately straightforward in design and construction. A basic six-panel grid predominates throughout much of the book, which keeps things simple and allows the story to flow at a gentle, even pace. And Mendes makes the most of this self-imposed limitation, varying angles and shifting focus from panel to panel to make each page work as a satisfying whole. Individual panels can linger on a single flower or open out to encompass a vast expanse of countryside. The grid is broken on occasion by horizontal or vertical panels that slow things down, build tension, or give bursts of dynamism at carefully selected moments, as when Marian finally fights back against Ray after he’s knocked Edie unconscious.

Midway through her childhood Edie returns to the care of her grandparents, Leland and Tess, a kindhearted couple who in many ways form the emotional core of the story. They shine as beacons of love, protection, and good humor in an otherwise pretty bleak world, and having already lost a daughter, they are determined to provide their grandchild with the kind of life she has never known before: stable, loving, and filled with the routine wonders of life in the country. It is these small moments of joy, laughter, and repose that save The Weight from becoming a simple study in human misery, and Mendes captures them with a hushed, understated simplicity, often without a word being spoken.

Economy of writing is a trademark of Mendes’ style, and The Weight is no exception. Dialogue is terse for the most part and absent entirely for long stretches of the book, which undoubtedly works to its advantage. After all, this isn’t a culture in which people open up about their deepest feelings, and the silences that pass between them often resonate more powerfully than words ever could. Thankfully, Mendes is adept at saying a lot with very little, skillfully conveying emotion through subtle shifts in facial expression and body language. She communicates anything from hatred, fear, grief, relief, surprise, and grim determination without a syllable being spoken. A tragic four-page sequence closing the first act is a masterclass in silent suspense, conjuring a sense of creeping dread by focusing on small details - an upturned table, a spilled coffee cup, a shock of hair - unfolds the terrible reality confronting the reader.

Economy of writing is a trademark of Mendes’ style, and The Weight is no exception. Dialogue is terse for the most part and absent entirely for long stretches of the book, which undoubtedly works to its advantage. After all, this isn’t a culture in which people open up about their deepest feelings, and the silences that pass between them often resonate more powerfully than words ever could. Thankfully, Mendes is adept at saying a lot with very little, skillfully conveying emotion through subtle shifts in facial expression and body language. She communicates anything from hatred, fear, grief, relief, surprise, and grim determination without a syllable being spoken. A tragic four-page sequence closing the first act is a masterclass in silent suspense, conjuring a sense of creeping dread by focusing on small details - an upturned table, a spilled coffee cup, a shock of hair - unfolds the terrible reality confronting the reader.

Despite all this, one of The Weight’s many strengths is that Mendes, informed by a deep-rooted sense of empathy, holds back from judging her characters even when their actions are clearly reprehensible. While she certainly doesn’t seek to excuse her characters' abusive behavior, she is aware that their lives are, in many ways, just as circumscribed by arbitrary rules and expectations as their victims', and their anger and violence stem, at least in part, from their impotence in the face of things they can’t control.

The characters are flawed in their own way; complex human beings burdened by the weight of limited hopes and truncated dreams. Edie is kind and sensitive at heart - someone who will hold solemn funeral rites for a dead rabbit or form a bond with a newborn bull - but her compassion is overwhelmed by her deep-rooted anger. Marian, despite being fearful of the violent consequences of her relationship with Ray, is unable to free herself from his brutality. Even Leland and Tess, devout in their love for their granddaughter, pressure her into a loveless marriage simply because it’s what’s expected. It is this willingness to accept the reality of human failings and express them so convincingly that makes The Weight such an engrossing journey.

Way back in 2018, Mendes said she expected the book would run to about 400 pages and span the entirety of Edie’s life. Fast forward to 2025, and it’s reached 600 pages while our protagonist has barely made it out of her teens. And, although the climax of the book may offer a moment of long-awaited catharsis, the look of sheer bewilderment and terror in Edie’s eyes on the final page signals that it’s hardly a happy ending, and that her journey is only just beginning. Of course, plans can change over the course of a decade, but it’s tempting to think there might be a sequel somewhere down the line. And, if this enthralling and highly accomplished effort is anything to go by, it would undoubtedly be worth the wait.

The post The Weight appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment