My Nana’s house had dolls lining the shelves in every room, and a refrigerator with a drawer full of plastic half-and-half capsules, like the kind the server brings you at an IHOP. The vanity in her bathroom was littered with a mix of fancy-looking beauty products in glass bottles and long expired coupons clipped from Sam’s Club fliers, and for some reason, regardless of the time of day or year, anytime you turned the television The Monkees was on. I loved going to my Nana’s house. Reading Molly Colleen O’Connell’s The Shriekers feels like being there, equal parts childhood dreamscape and a world so out of whack that you’re pretty sure you shouldn’t be left in it unsupervised.

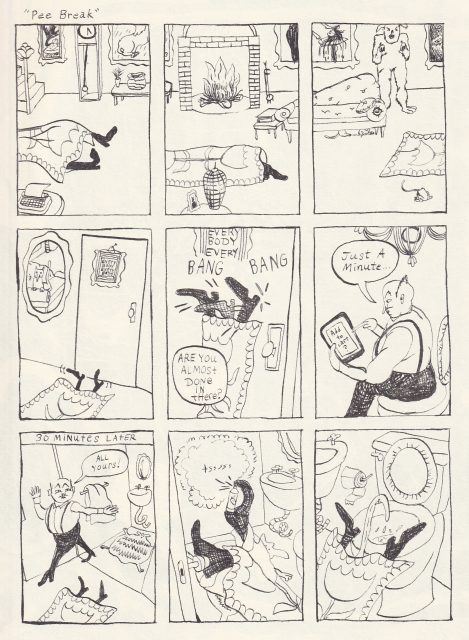

I think Shriekers is for kids. Which is to say, I have let my kid read it and if you came into our comic shop [the author co-owns the Philadelphia store, Partners and Son] with a kid I would try to sell it to them. Sure, Jason Voorhees is lurking on the cover of Issue 1 and Michael Myers is hiding in a clothesline in Issue 2, and maybe not every kid will appreciate the Magnum Opus joke, but the Toilet Seance in Shriekers 2 is enough to sell me on the idea that it is totally kid-friendly. I have shown up to a playground wearing O’Connell’s “Feral MILF” t-shirt on more than one occasion, so take my recommendations for kid friendliness with a grain of salt, but once the kids graduate from Seuss and start asking the tough questions, like what happens when the Vug in the Rug has to pee, Shriekers comes through in a way that Dogman could only dream about. The Shriekers series lives in a world that feels spiritually bound to Pippi Longstocking while understanding the reality that a YouTuber with two first names is making millions selling energy drinks to kids. The mix is part unchaperoned whimsy, part feral child shopping spree, and oh-so-many possums.

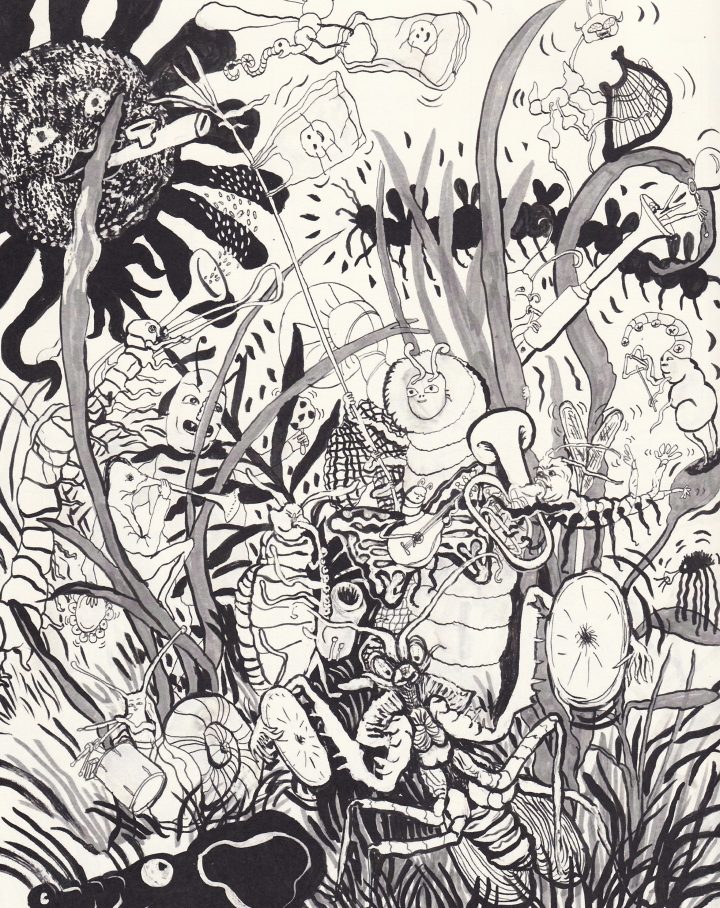

O’Connell’s drawing has a lot of music to it, with the improvisational energy of early aughts Laura Owens paintings. More than one strip includes a saxophone with a surprise inside (Snakes! Spiders!) and another includes an “ear horn” that pulls a carrot shaped parasite out of, well, an ear. The lines of her drawing move accordingly, skronking with the horns. They are jerky and expressive and every action has one more motion line than it needs, but who’s counting. Her characters dance with the confidence of children in a room full of fawning adults, their bodies grow tails and twist into impossible positions and their arms all seem to include an extra muscle, no doubt because her lines are doing visual aerobics. O’Connell’s Shriekers could sit alongside Amanda Vähämäki or Jesse Jacobs. Less subtle than Pixie Lice and less cynical than New Pets, Shriekers shares with these titles the confusion of childhood and the fantastic ways children contort reality. While Vähämäkii gives her fairy characters “Little Hexes” and Jacobs gives his characters horrific modular dogs(?), O’Connell’s Shriekers conjure up a friendly “lurking presence” and cultivate rashes with pride.

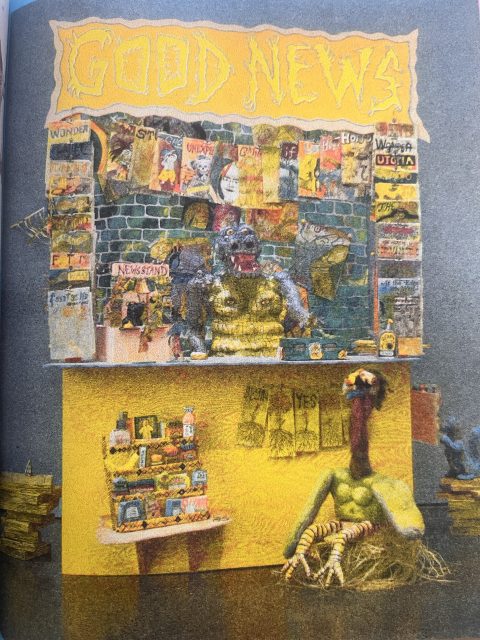

If you already know O’Connell’s work you may see some familiar faces. Alligators, swamp birds, spiders, skeletons, and clowns appear in all her books. In Shriekers they sing karaoke and spy on their neighbors. In Pebbles they straddle super highways and attack audience members. In Who’s Afraid of a Florida Woman they decorate the margins of her poetry (often about clowns) and send sexts. (It’s worth noting that Who’s Afraid of a Florida Woman, O’Connell’s poetry/prose/art book published by Colorama, deserves its own 1000–2000 word review, but if I wrote it they would all be “wow”.) As the title suggests, O’Connell is from Florida, which of course explains the alligators, and perhaps the clowns as well. Florida Woman also includes images from a sculptural installation of a newsstand created by O’Connell; PeeWee’s Playhouse meets Fischli and Weiss, a trompe l’oeil for the world of Shriekers. Seeing these images adds another dimension, literally, to O’Connell’s body of work. I am a real sucker for a multimedia artist, even when they’re clearly more adept at one form than another (Macaulay Culkin novels, Adrien Brody paintings), but it is incredibly satisfying when someone is actually good at all the media. O’Connell’s comics, poetry, sculpture, and T-shirts, are all so perfectly intertwined I would be seething with jealousy if I wasn’t having such a good time!

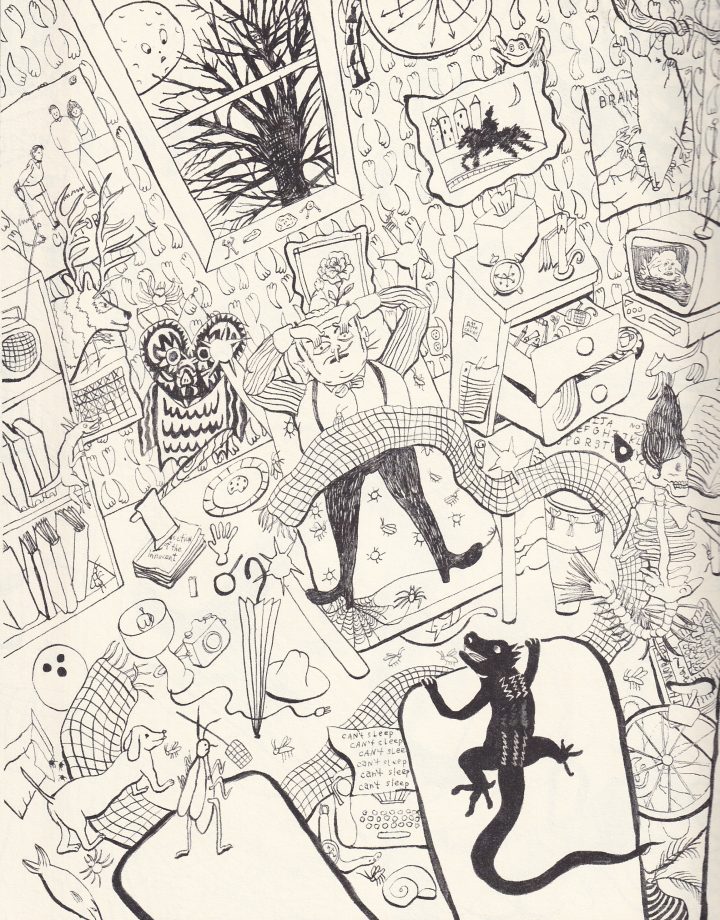

To act as if Shriekers is all frolic is a disservice to the cultivated chaos of O’Connell’s drawing. There are moments in both issues when the pages are so overrun with action they become anxiety-inducing. While Shriekers as far as I can tell is set in the present, with nods to internet culture like YouTube channels and “Wellness”, the internet of Shriekers is refreshingly backgrounded, functioning as a device to draw you further into the actual home: the wallpaper, the overstuffed refrigerator, the seemingly endless closets and drawers to open and peek into. The densely drawn pages are mostly vignettes depicting “nature” scenes of the comics, like bugs playing tubas or a frog catching a ride back to the wetlands in a heron’s beak. In these, O’Connell’s attention to detail feels like the work of someone who spends time walking in the woods or at least in an overgrown backyard. These drawings don’t revere the “real” world, but they do seem to find it more interesting. These pages are maybe most like Highlights magazine’s “Hidden Pictures”, so layered with objects that it’s tempting to grab a pen and circle a few. There are mazes to complete in each issue, one of which is drawn completely as curly cords from a rotary phone, an object that seems more difficult to explain to a kid than the strip where a possum fakes his death for the insurance.

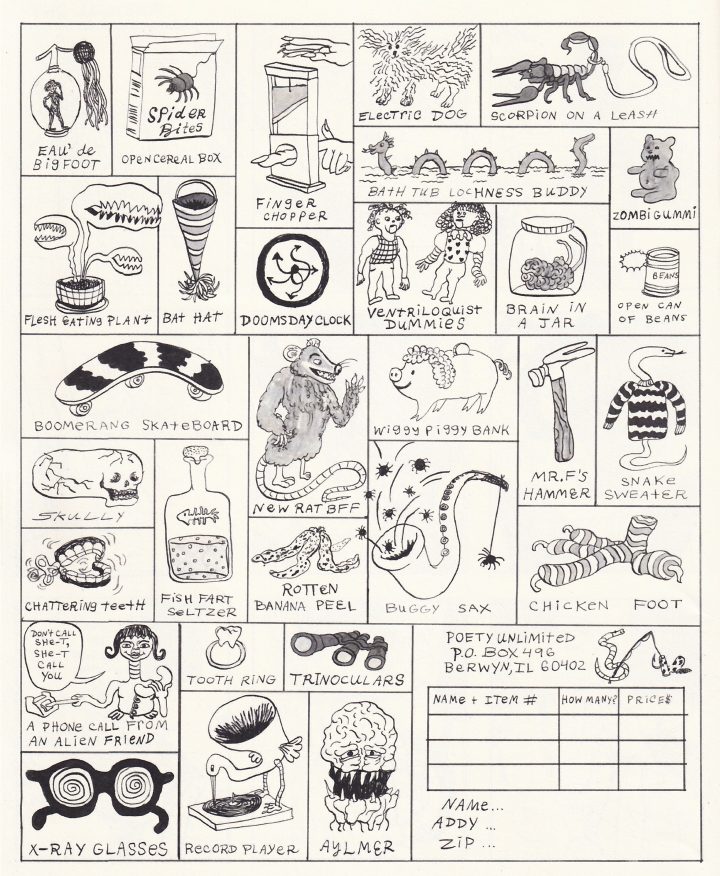

While we see characters looking directly out from panels that urge us to “Subscribe Now!” the mood of Shriekers is more landline than online. O’Connell’s work feels like she grew up when the internet was still new enough to believe you had to forward that email to 20 people or be forever cursed (maybe I’m projecting). There is something almost quaint in the way she depicts anything from the World Wide Web. In Shriekers, the internet in not a sinister place, it’s actually fun (if Ghouly Gully tutorials had a Patreon, I would definitely support it), keeping the real clutter in the real world. In “Shopping Spree”, the last comic of the first issue, Marge is calling into a QVC-like television channel to order a ridiculous number of ridiculous things: a baker’s dozen of denim handcuffs, ten bottles of vintage hot cheese, the last remaining 33 squirrel pelts. When the character Regimold walks in and immediately heads to his room, where he desperately tries to sleep, surrounded by swirling piles of belongings (mermaid skeletons, scarves, half-eaten plates of food, etc.); this is a family drowning in their ridiculous things. A note taped to the bedside table reads “Eat More Candy” and another says “Goals: Get better at letting people know when they are bugging me”. Meanwhile, a typewriter on a heap near an unplugged lamp and a unicycle endlessly types “Can’t Sleep Can’t Sleep Can’t Sleep.” Concluding the story with this image jolts us out of our silly state. Turns out all this play is exhausting.

To be sure, the exhaustion is a good thing. The real world is tiring, but like a kid who spent all day at a waterpark with no lines or an adult who spent all night at a karaoke bar that only played their favorite songs, the Shriekers are fatigued from fun. You will be overwhelmed and overstimulated when you read it. You might need a snack. You will likely want to go full Marie Condo on some of the pages, only to realize every little object sparks joy. Grab a copy and share it with a kid or with the half exposed head you planted in your backyard, or just curl up with it on your couch and read it with your new rat bff. To quote the Letter to the Editor section at the beginning of issue two “shenanigans, hijinks, and reverie belong to us all!”

The post Shriekers 1&2 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment