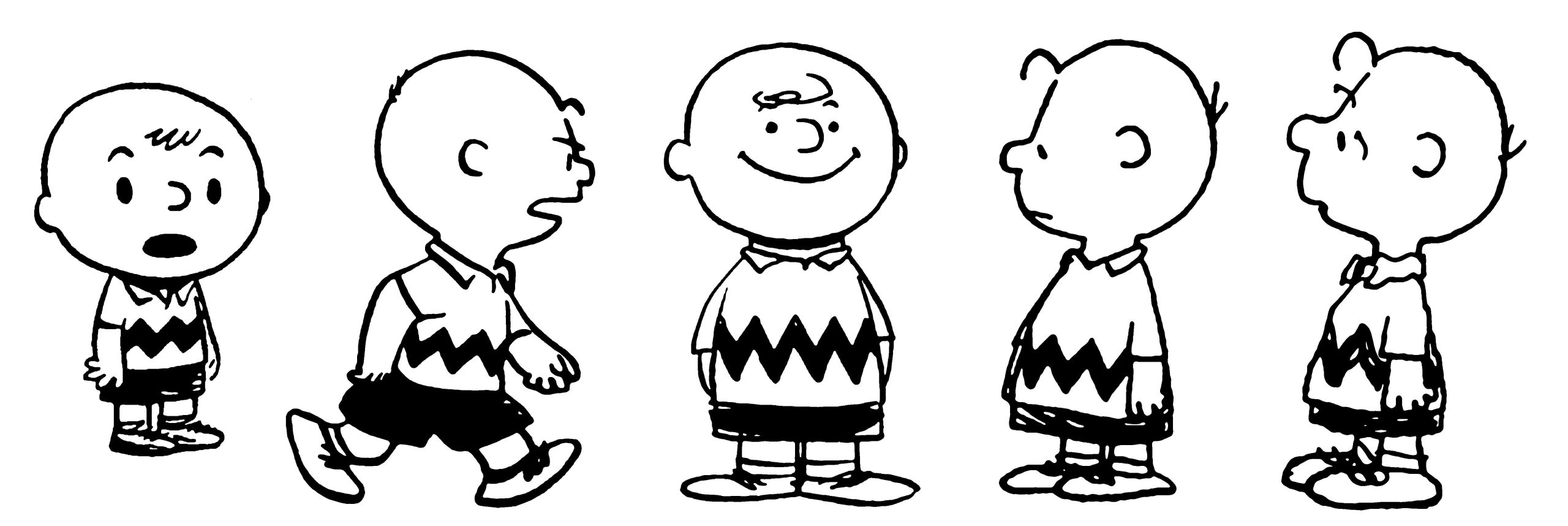

Feeling like it's been only 75 years since the first appearance of Charles Schultz' Peanuts in newspapers nationwide?

Your sense of time is as sharp as ever — today is indeed the semi-sesquicentennial of perhaps the best-known comic strip ever made, the popularity of which has been proven to you, dear reader, by the number of times it has been mentioned to bridge the gap by well-meaning acquaintances searching for connection, once they find out you are into comics.

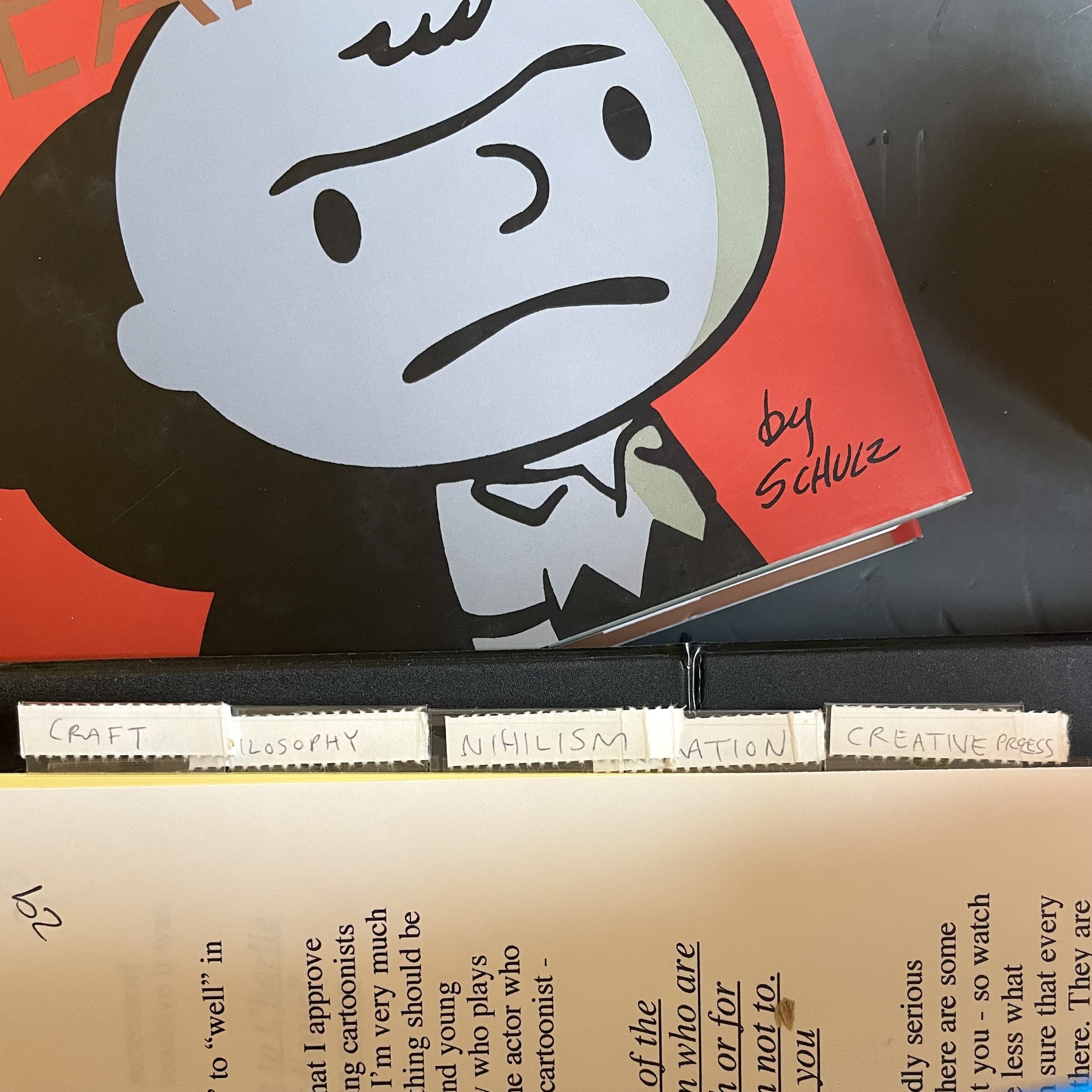

Please enjoy this excerpt from Gary Groth's Charles M. Schulz interview, which ran in The Comics Journal #200, December 1997.

Charles M. Schulz was born November 25, 1922, in Minneapolis. His destiny was foreshadowed when, at the age of two days, an uncle nicknamed him Sparky (after Barney Google's racehorse, Spark Plug).

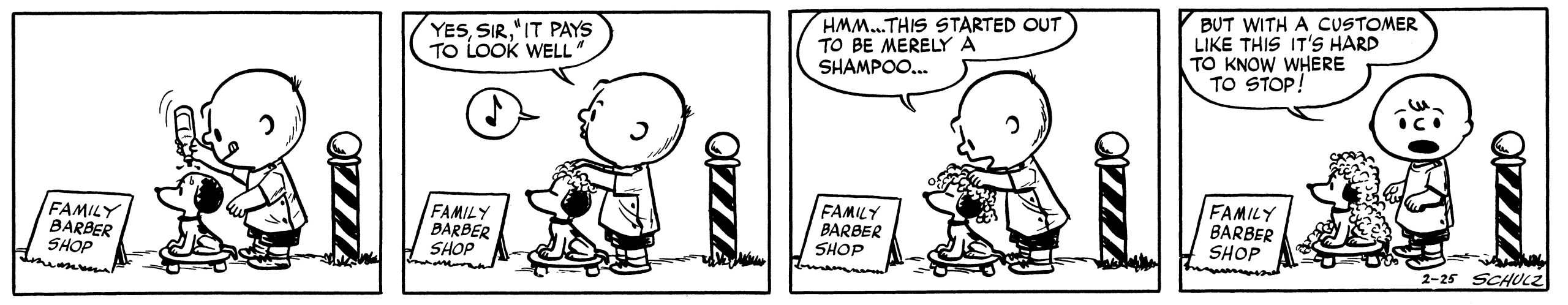

"My dad was a barber," Schulz recalled. "I always admired him for the fact that he and my mother had only a third-grade education, and from what I remembered hearing in conversations, he worked pitching hay in Nebraska one summer to earn enough money to go to barber school, got himself a couple of jobs, and eventually bought his own barber shop. And I think he at one time owned two barber shops and a filling station, but that was either when I was not born or very small, so I don't know much about that." Except for a misguided year-and-a-half interlude spent in Needles, California ("an eerie and eternal summer" Schulz called it), he grew up in St. Paul. "We settled in a neighborhood about two blocks from my dad's barbershop, and most of my playtime life revolved around the yard of the grade school across the street from our apartment."

By all accounts, Sparky Schulz led an unremarkable, albeit sheltered, childhood. He was an only child, close to both parents. His father evidently nurtured his interest in comics: according to his biography by Rita Grimsley Johnson, his father's "one passion was the funny papers. He loved comics and read them the way some men read box scores or racing forms — with intensity and devotion. He bought four Sunday newspapers every week, for the comics, picking up the two local papers on Saturday evening, hot off the presses.

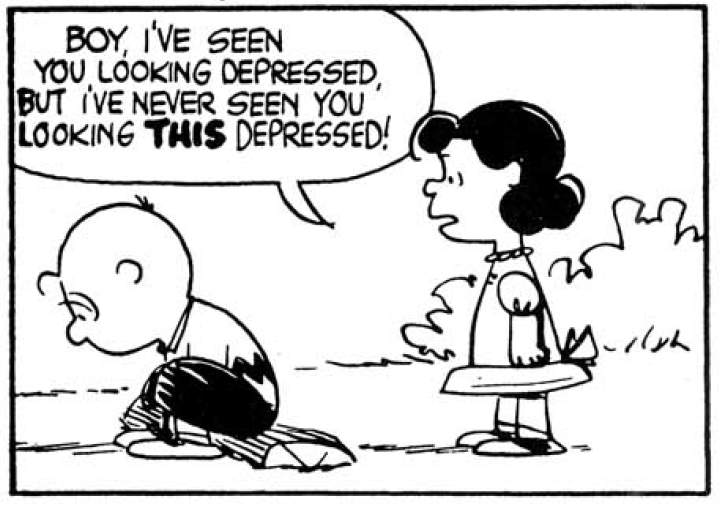

His academic career was erratic. He was such an outstanding student at Richard Gordon Elementary School that skipped two grades, but began to flounder later at St. Paul's Central High School (He became a shy, skinny kid with pimples and big ears, nearly 6 feet tall and weighing only 136 pounds") — perhaps not so coincidentally, at the same time kids are going through their cruelest, most status-conscious period of socialization. The pain, bitterness, insecurity, and failures chronicled in Peanuts appear to have originated from this period of Schulz's life. Schulz reproduced a report card from high school in Peanuts Jubilee (1975), under which read the first-person caption: "This report card is printed to show my own children that I was not as dumb as everyone has said I was." (The present perfect tense Schulz chose is instructive.) His acute sense, and resentment, of small but hurtful injustices also seem to stem from this period and continue to be deeply felt to this day. "I kind of resented the whole public school system at that time," he said. "It didn't cater to the many kids who weren't big and strong. The gym teachers paid attention only to the school athletes. The rest of us were shunted aside. I really resented that." Or consider this wounded recollection: "It took me a long time to become a human being. I was regarded by many as kind of sissyfied, which I resented because I really was not a sissy. I was not a tough guy, but I was good at sports.... So I never regarded myself as being much, and I never regarded myself as being good-looking, and I never had a date in high school, because I thought, who'd want to date me? So I didn't bother, and that's just the way I grew up."

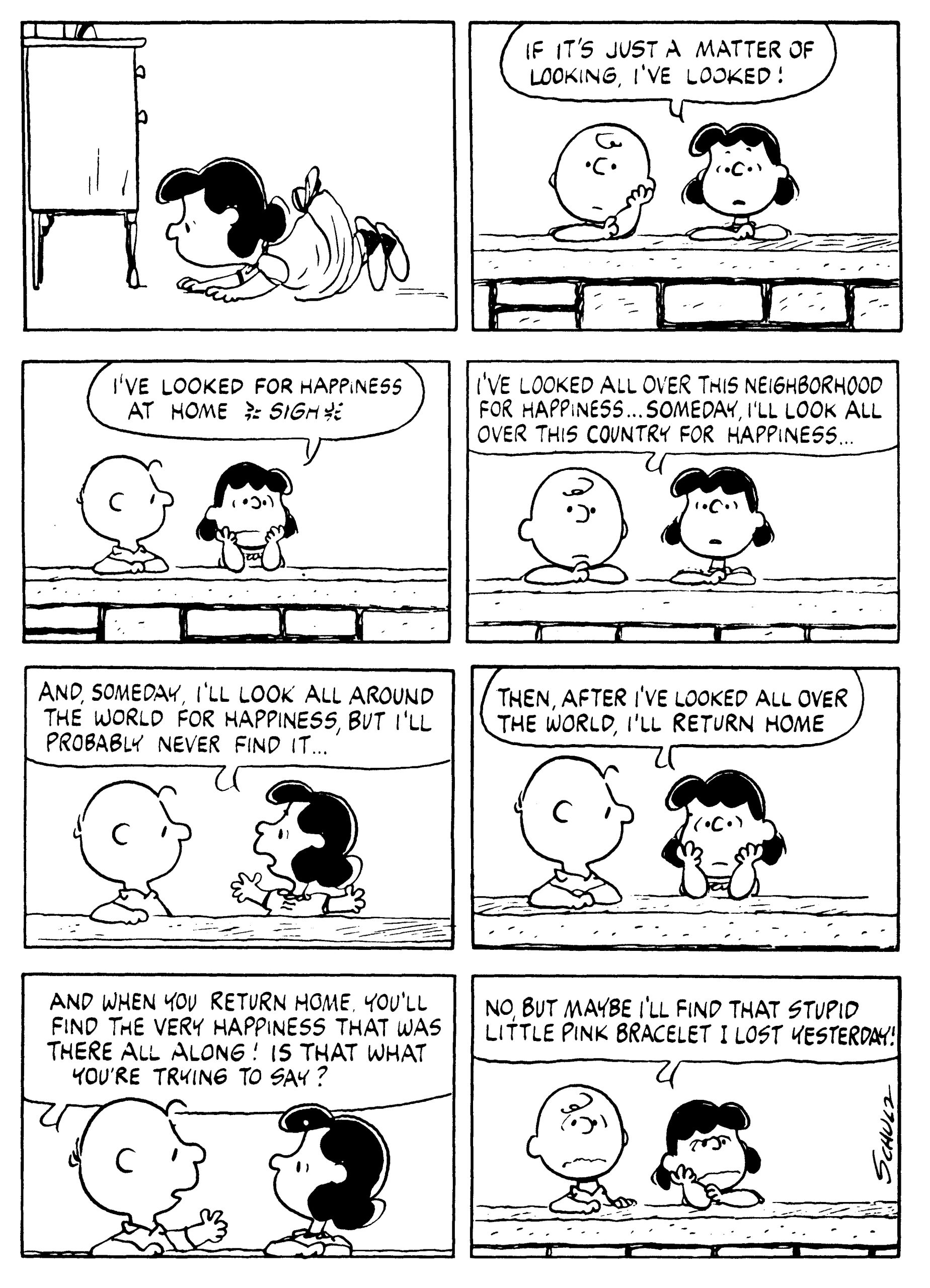

Through Peanuts, Schulz has touched upon a truth that we are perhaps too embarrassed to acknowledge but which may paradoxically account for the strip's universal popularity: that the cruelties and slights we suffer as a part of growing up, regarded by adults as inconsequential, or, at any rate, ineradicable, follow us to the grave, affecting our perception and behavior in adulthood. Or, as Umberto Eco put it: "[The Peanuts characters] affect us because we realize that if they are monsters it is because we, the adults, have made them so. In them, we find everything: Freud, mass-cult, digest culture, frustrated struggle for success, craving for affection, loneliness, passive acquiescence, and neurotic protest. But all these elements do not blossom directly, as we know them, from the mouths of a group of children: they are conceived and spoken after passing through the filter of innocence."

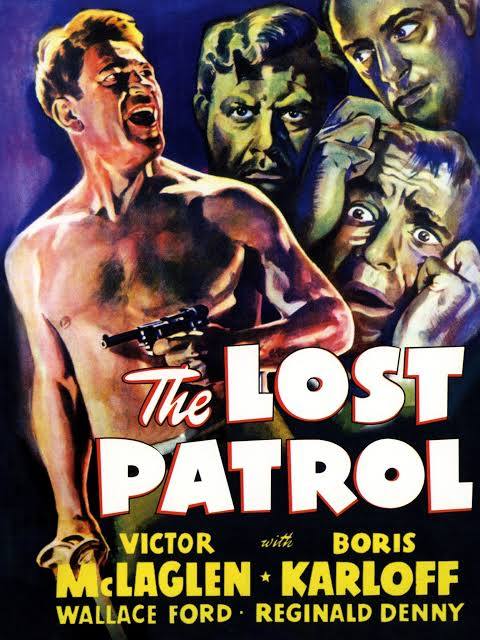

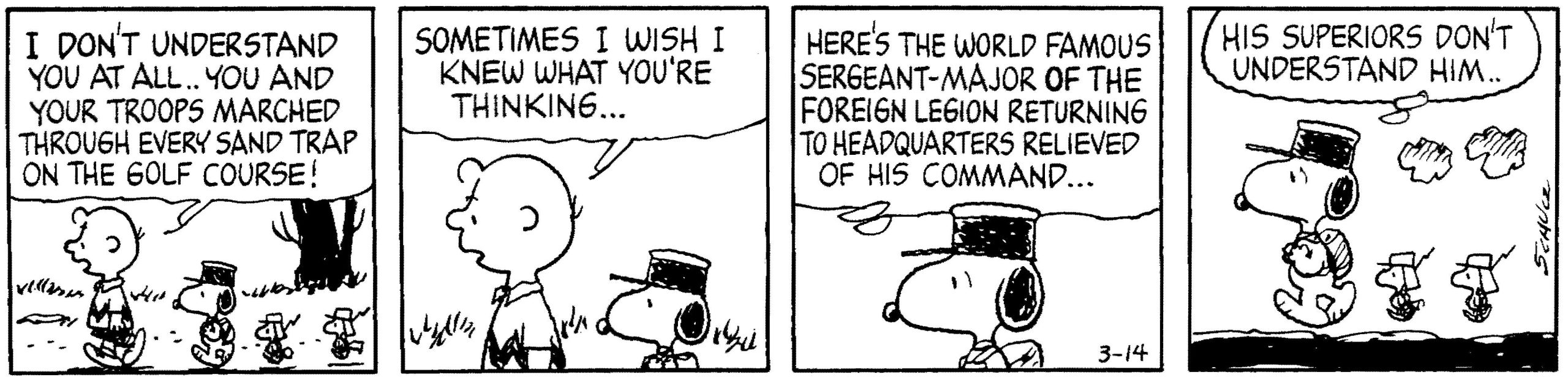

Although Schulz enjoyed sports, he also found refuge in solitary activities: reading, drawing, watching movies. "The highlight of our lives was, of course, Saturday afternoons, going to the local theatre. We would buy a box of popcorn for a nickel from a popcorn shop a few stores down from the theatre, and then we'd go to the afternoon matinee. My favorite movie, I still remember, was Lost Patrol with Victor McLaglen. I loved those desert movies, which is why I like drawing Snoopy as the foreign legionnaire."

He bought comic books and big little books, pored over the newspaper strips, and copied his favorites. "Usually I tried to copy the style of Buck Rogers, but I was also crazy about all of the Walt Disney characters, and Popeye… and the characters in Tim Tyler's Luck… Clare Briggs influenced me considerably... I also thought there was no one who drew funnier and more warm-hearted cartoons than J.R. Williams." He was quickly becoming a connoisseur; his heroes were Milton Caniff, Roy Crane, Hal Foster, and Alex Raymond. In his senior year in high school, his mother noticed an ad in a local newspaper for Federal Schools, a "correspondence plan for aspiring artists" (now called Art Instruction Schools). "She came in one night and she said, 'Look here in the newspaper. It says, "Do you like to draw? Send for a free talent test." So I sent it in, and a few weeks later, a man knocked on the door, and it was a man from the correspondence school. And he sold us the course." Schulz's father paid the $170 tuition in installments. Schulz completed the course and began trying, unsuccessfully, to sell gag cartoons to magazines. (His first published drawing was of his dog, Spike, which appeared in a 1937 Ripley's Believe It or Not installment.)

He was drafted in 1943 at the same time his mother was diagnosed with cancer. The timing and the circumstances made leaving home particularly excruciating for Schulz. He was home one weekend when his mother looked up at him from her bed and said, "I suppose that we should say good-bye, because we probably never will see each other again." She died the next day. His father drove him back to Fort Snelling after her funeral, from which he shipped out to Camp Campbell, Kentucky, later that day. "I remember crying in my bunk that evening," he recalled. His mother's death "was a loss from which I sometimes believe I never recovered."

Schulz was discharged after the War and started submitting gag cartoons to the various magazines of the time. But his first breakthrough came when Roman Baltes, an editor at Timeless Topix, a comic magazine owned by the Roman Catholic Church, hired him to letter adventure comics. Soon after that, he was hired by his alma mater, Art Instruction, to correct student lessons returned by mail. "For the next year, I lettered comic pages for Timeless Topix, working sometimes until past midnight, getting up early the next morning, taking a streetcar to downtown St. Paul, leaving the work outside the door of Mr. Baltes's office, and then going over to Minneapolis ot work at the correspondence school."

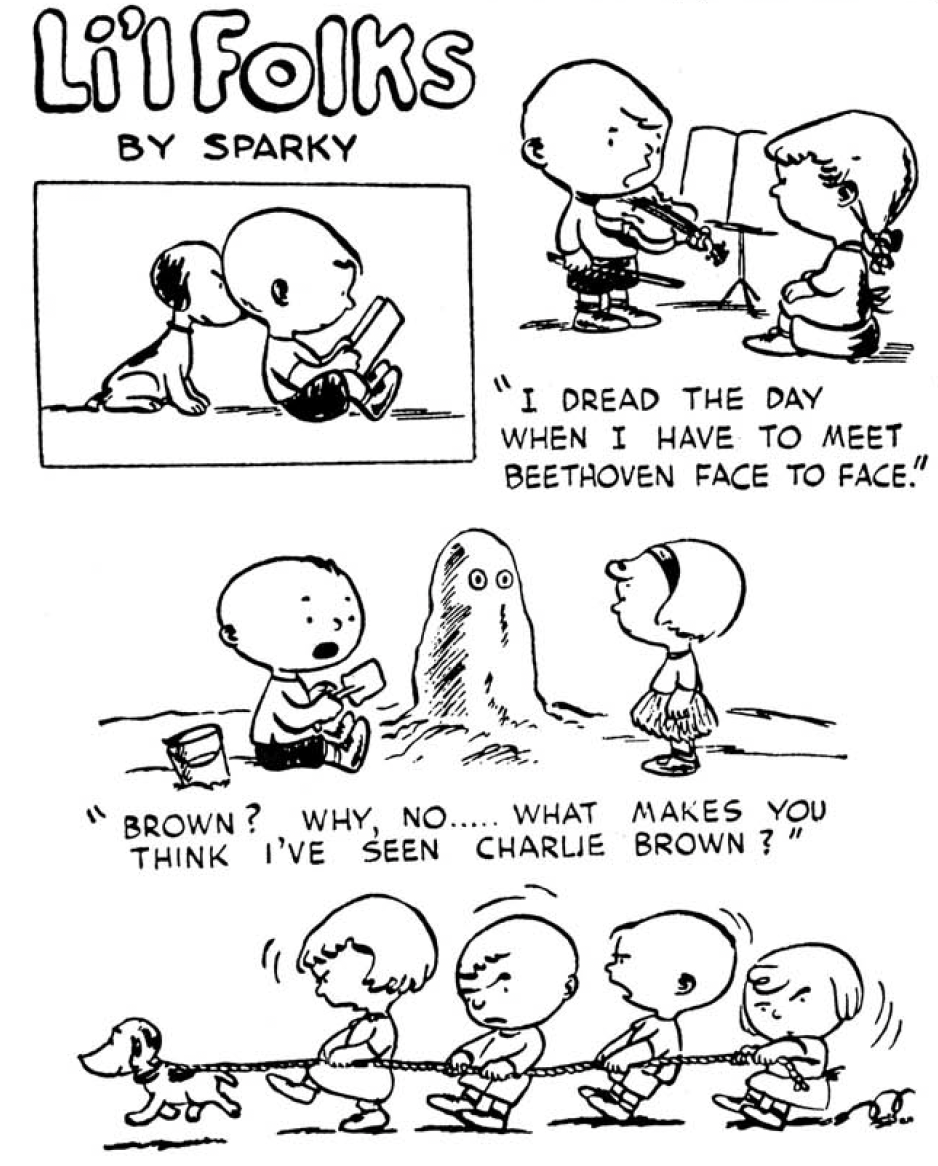

His next break was selling 71 cartoons to the Saturday Evening Post between 1948 and 1950, during which time he sold a weekly comic feature called Li'l Folks to the local St. Paul Pioneer Press. It was run in the women's section and paid $10 a week. "One day Roman [Baltes] bought a page of little panel cartoons that I had drawn and titled 'Just Keep Laughing.' One of the cartoons showed a small boy who looked prophetically like Schroeder sitting on the curb with a baseball bat in his hands talking to a little girl who looked prophetically like Patty. He was saying, I think I could learn to love you, Judy, if your batting average was a little higher. Frank Weing, my fellow instructor at Art Instruction, said, 'Sparky, I think you should draw more of those little kids. They are pretty good.' So I concentrated on creating a group of samples and eventually sold them as a weekly feature called Li'l Folks to the St. Paul Pioneer Press." After writing and drawing the feature for two years, Schulz asked for a better location in the paper or for daily exposure, as well as a raise. "When he turned me down on all three counts, I suggested that perhaps I had better quit. He merely stated, 'All right.' Thus endeth my career at the St. Paul Pioneer Press."

He started submitting strips to the newspaper syndicates. "I used to get on the train in St. Paul in the mornings, have breakfast on the train and make that beautiful ride to Chicago, get there about three in the afternoon, check into a hotel by myself, and the next morning I would get up and make the rounds of the syndicates. At this time, I was also becoming a little more gregarious and was learning how to talk with people. When I first used to board the morning Zephyr and ride it to Chicago, I would make the entire trip without talking to anyone. Little by little, however, I was getting rid of my shyness and feelings of inferiority, and learning how to strike up acquaintances on the train and talk to people."

He had a near-miss at the NEA syndicate: "I opened a… letter from the director of NEA in Cleveland saying he liked my work very much. Arrangements were made during the next few months for me to start drawing a Sunday feature for NEA, but at the last minute, their editors changed their minds and I had to start all over again." In the Spring of 1950, Schulz received a letter from Jim Freeman, United Feature Syndicate's editorial director, announcing his interest in his submission, Li'l Folks. Schulz boarded a train in June for New York City to discuss drawing a strip for them. Schulz self-depracatingly describes his successful trip thusly:

"I had brought along a new comic strip I had been working on, rather than the panel cartoons which United Feature Syndicate had seen. I simply wanted to give them a better view of my work.

"I told the receptionist that I had not had breakfast yet, so I would go out and eat and then return. When I got back to the syndicate offices, they had already opened up the package I had left there and, in that short time, had decided they would rather publish the strip than the panel. This made me very happy, for I really preferred the strip to the panel.

"I returned to Minneapolis filled with great hope for the future and asked a certain little girl to marry me. When she turned me down and married someone else, there was no doubt that Charlie Brown was on his way. Losers get started early."

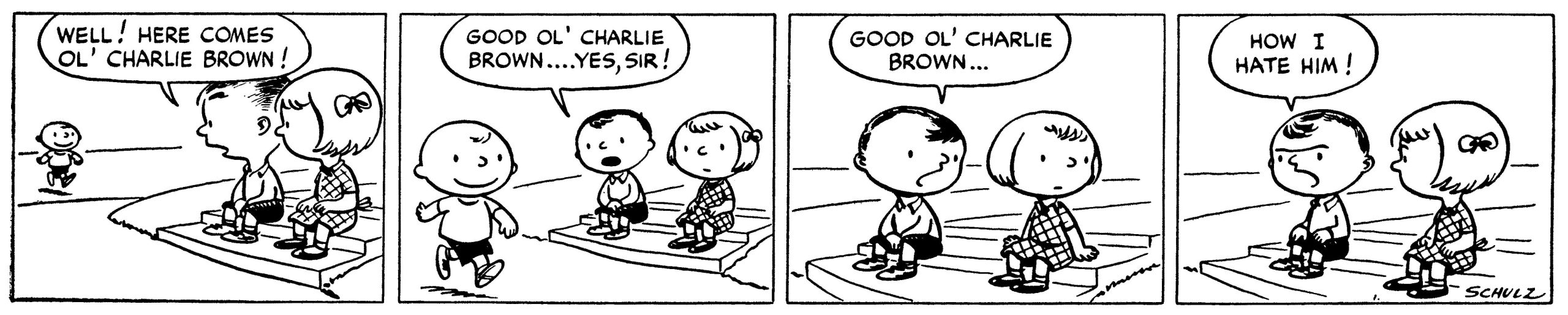

The first Peanuts strip appeared October 2, 1950.

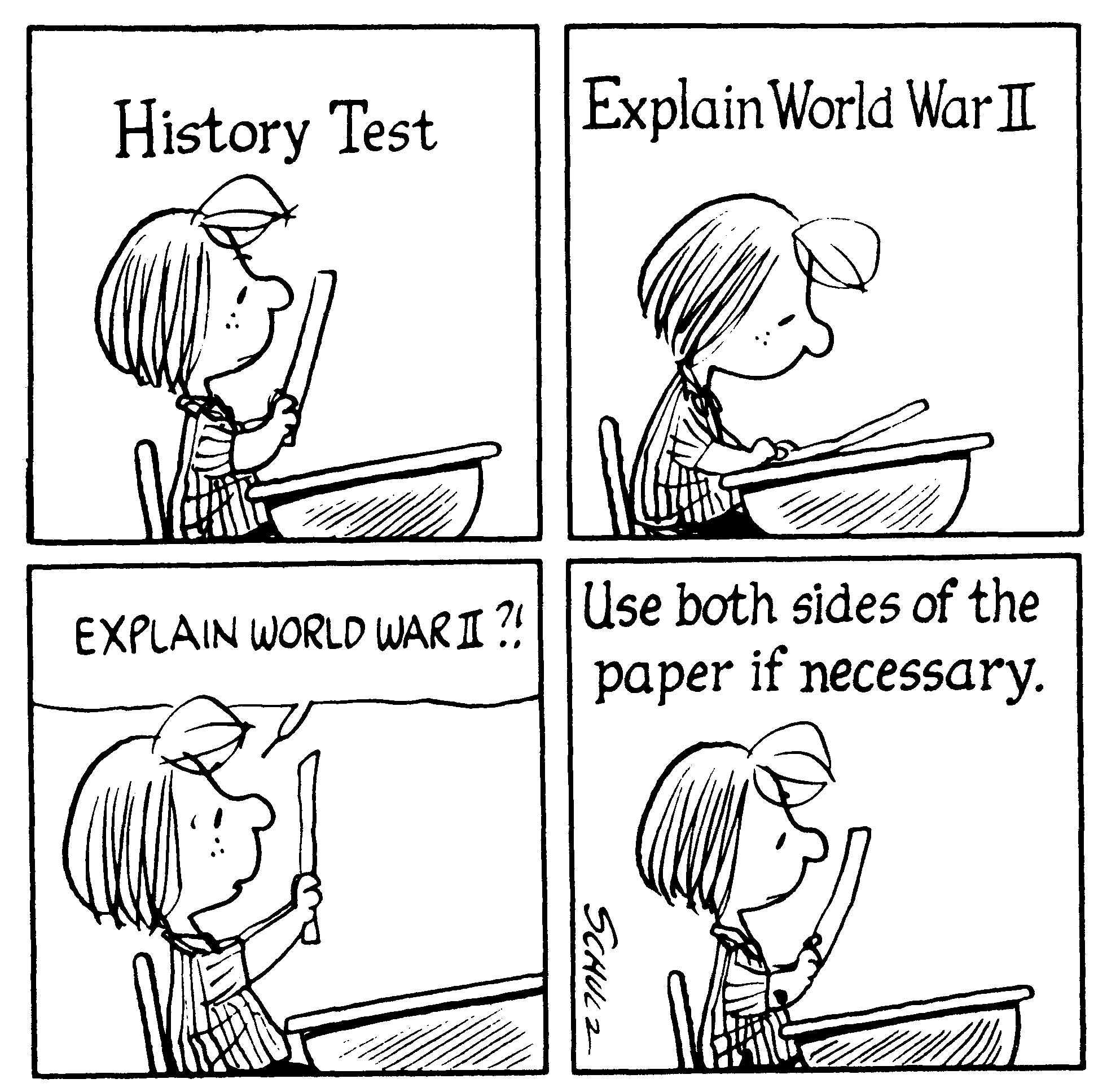

Prior to Peanuts, the province of the comic page was that of gags, social and political observation, domestic comedy, soap opera, various adventure genres. Although Peanuts has changed, or evolved, over the 47 years Schulz has written and drawn it, it remains, as it began, an anomaly on the comics page- a comic strip about the interior crises of the cartoonist himself. After a painful divorce in 1973 from which he had not yet recovered, Schulz told a reporter, "Strangely, I've drawn better cartoons in the last six months — or as good as I've ever drawn. I don't know how the human mind works." Surely, it is this kind of humility in the face of profoundly irreducible human question that makes Peanuts as universally moving as it is.

It's worth being reminded that Charles Schulz is one of the greatest cartoonists of the 20th century, something that the global phenomenon of Peanuts by way of all the merchandising and licensing and media spin-offs may obscure. We hope we've accomplished that and more with this issue of the Journal. We also hope the section of appreciations, commentary, and reminiscences (which Schulz was deliberately kept blissfully ignorant of) serves as a belated — and surprise — 75th birthday present.

This interview was conducted in two sessions: once in October in Charles Schulz's office in Santa Rosa, California, and a shorter one over the phone a month later. My thanks to Sparky for his generous time, hospitality, and professionalism. He copy-edited the interview (in record time). I edited the interview for final publication.

GAG CARTOONIST

GROTH: In every interview I've read where you make reference to them, you've said that you sold 15 gag cartoons to the Saturday Evening Post in the late 40s.

SCHULZ: Oh, yeah.

GROTH: But you actually sold 17.

SCHULZ: Did I?

GROTH: Yeah.

SCHULZ: That's pretty good.

The odd thing is that the little kid ones went the best. But I remember this one [January 1, 1948] came about the morning after Hary Truman beat Thomas Dewey, I was so bitter and disgusted about the whole thing, and some old woman came in the room that day. She was one of the instructors, and she was all excited about it, and I remember turning to someone and saying, "Huh! I sleep well enough at night, it's living during the day I find it so hard." And I sent the rough into the Post and they okayed it, and all of the sudden I realized that I didn't have any drawing style. I had to draw this thing, and I hadn't developed any style at all. Because I had been drifting into drawing the little kids, and I was working on that style, and all of the sudden I had to draw these adults. It was a very mechanical style, and I wasn't proud of it at all.

GROTH: You found it difficult to stylize adults because you had gotten so used to drawing kids?

SCHULZ: Yeah. Uh-huh.

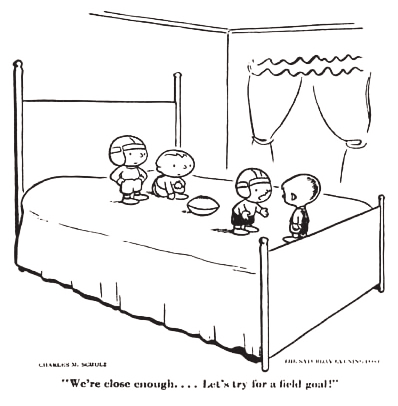

Taking ordinary things like the bed and turning them into a football field and a race track was a gimmick. Of course, since then, I've drawn a million bird baths. This was one of my favorites [Feb. 1, 1950], and they changed the word; it's a misprint, it should have been, "Oh, we got along swell." Rather than, "We get along swell." That doesn't make sense.

But my style is beginning to develop a little bit [at this point]. This one was quite successful too; a gimmick learned how to draw, and this was reprinted a couple of other places. I got $60 for this, and then I made $15 or $20 other dollars reprinting it someplace.

I was on the right track. That's how it all started. I was very ambitious. But I couldn't sell to any other magazine. I sent, I know, to Collier's and a couple of others.

But I couldn't sell any other magazines. But apparently John Bailey liked them, and he was very good to me, he must have been good, as I've talked to Mort Walker and others, he was good to cartoonists, and I sent him one batch of roughs once, and he tore out little scraps and corners of paper and attached them to each one telling me what was wrong with them, and why he didn't buy it. Which took time. But he must have felt it was important. I never met the man, but that was good.

GROTH: He must have seen potential.

SCHULZ: Yeah, I suppose. A long time ago.

GROTH: What kind of rejections did you get from other magazines?

SCHULZ: Just rote rejection slips.

I didn't do a lot of [submitting]. Probably This Week, which was another market, and Collier's. I don't recall sending them to the New Yorker when I was at this stage, because I knew it was hopeless. So I didn't try that. A lot of amateurs do, of course. But that's a brutal business. I used to get my mail at my Dad's barber shop when I came home from Art Instruction School. We lived around the corner from the shop.

I'd open the envelope, and there'd be a little note that would say, "Here's an OK for you". The whole world suddenly became bright and cheery. But if it said, "Sorry, nothing this week," then it was so depressing. [laughs] That's why I was so glad when I finally sold the comic strip for every idea that I had thought of was used. And have a change of pace. I think a comic strip is very important to have a change of pace. That's why I have such a good group, I've got a repertory company. And I can do things that are really stupid, and give them to Snoopy, things that are really corny, kind of dumb. But they become funny because Snoopy doesn't realize how corny and dumb they are. Or else he and Woodstock will say something which is just silly, and they'll laugh and laugh and they'll fall off the doghouse on their heads or something. I like to do things like that. Just slapstick. And then try to do things that are more meaningful. A really good range of ideas. And I've said that almost everything that I think of somehow can be turned into a cartoon idea. I'm not restricted in the ideas. I can go in any direction that I want to go.

GROTH: And doing that also gives you a great latitude in terms of visuals.

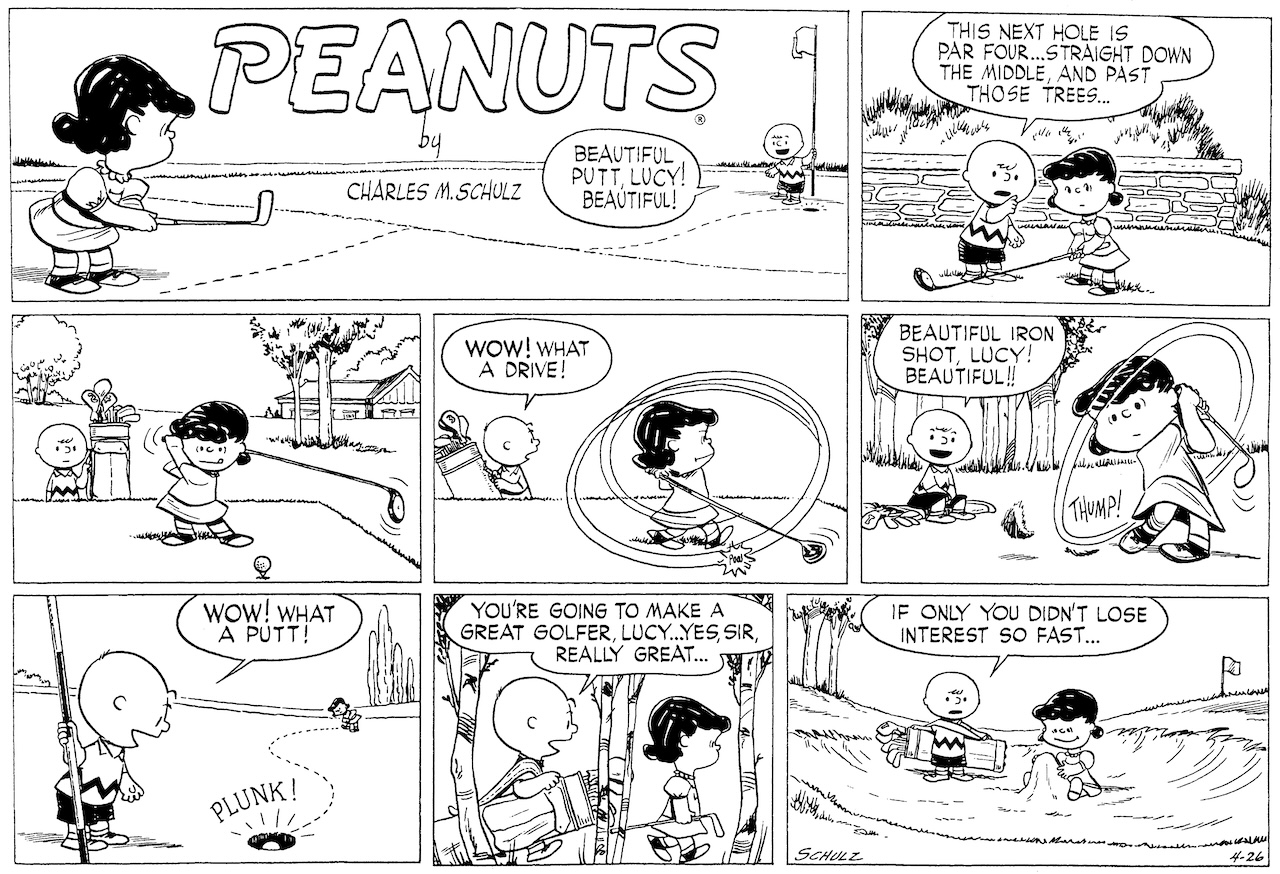

SCHULZ: Oh yeah. Visuals are extremely important. I think a lot of cartoonists these days have gotten away from that. It's the basis of what cartooning is. I've been quoted on this many times, that cartooning is still drawing funny pictures. If you don't draw funny pictures, then you might as well be writing for live television or some other form of entertainment. But visuals were extremely difficult. I think you can run out to the end very quickly. That's what worries me lately, as I turn 75 in a couple of months, that I might have done so many things with so many situations. How many funny pictures can you get out of Snoopy looking up and watching the leaf fall out of the tree? And yesterday I think I spent almost the whole afternoon trying to get something funny out of Linus sitting in a cardboard box trying to just slide down the hill. I really like drawing, and I came up with one idea, but I still can't decide if it's funny enough or not. So l abandoned it. I finally went into a totally different direction. But there's so many things that I really liked having done, I would like to just keep playing on these themes and variations as much as I can. But sometimes I feel like I've run right out to the end, and there are no more ideas anymore. I'm always amazed when I haven't done something for maybe ten years on something like that, and one day I think of one. And then I wonder, "Why in the world didn't I think of that ten years ago?" Why did it take me ten years? This is playing on the same theme, but this is the way it is. And I think this is one of the things you learn about after doing it for so long.

GROTH: That's the way I would think the imagination would work on such an organic life's work, where you're working on variations of a handful of themes over the course of a long time.

SCHULZ: And so much depends upon your own life, too. [laughs] I think critics and interviewers forget we still have another life we live.

GROTH: The demarcation between your life and your work is often blurred because you put so much of your life into your work.

SCHULZ: Well, yeah, and I find that people who don't know anything about it, friends of ours frequently say, "Oh, I know where you got that idea." And I want to say, "No, you don't." [laughs]

GROTH: What you just said about the convergence of ideas and drawings reminded me of something you said about the strip: "The type of humor that I was using did not call for camera angles. I like drawing the characters from the same view all the way through, because the ideas were very brief, and I didn't want anything in the drawing to interrupt the flow of what the characters were either saying or doing." Your respect for what you refer to as the ideas would appear to me to limit the scope of the drawings that you're able to do, and I know you take great joy in drawing. Did you ever want to draw in a way that the strip itself wouldn't allow?

SHULZ: I would like to, but it's too late. I've locked myself into this drawing style, and I can't escape from it. And I think for me to draw the way Hank Ketcham used to draw just wouldn't work. Hank was drawing panels from wonderful, different camera angles, reflections in mirrors and things like that. Which simply would never work in my strip. For one thing, it would make everything too realistic. And Dennis the Menace is pretty realistic. He even said to me once on the golf course — we were playing in the AT&T together. We didn't get a chance to talk very much, but one day we were talking about the features, and he said, "Your strip is really more of a fantasy, isn't it?" And I said, "Yeah, I guess maybe it is." [laughs] I didn't know he had even thought about it.

GROTH: Did you admire the Dennis the Menace panel?

SCHULZ: I admire the drawing tremendously, yeah. But I don't like annoying little kids. [laughter]

GROTH: Are you friends with Hank Ketcham?

SCHULZ: I'd like to think so. We don't know each other that well; we've never spent a lot of time together. Those days on the golf course at the tournament were the most we had ever spent, but even then, we didn't get to talk very much. We were too busy playing.

The cartoonist whom I feel I know the best these days, probably, would be Lynn Johnston.

GROTH: It doesn't seem like the cartooning community is very close-knit. Because Ketcham, as far as I can tell, is almost your exact contemporary.

SCHULZ: Yeah, yeah. Of course, he got started much quicker than I did. He and Gus Arriola both worked for Disney and so were quite accomplished before they even began [drawing strips]. Ketcham was also a successful gag cartoonist before I ever got started. Gus Arriola had worked for Disney; he was drawing Gordo before the war, and then he picked it up after the war. Gus is a little bit older than I am.

GROWING UP

GROTH: When you were growing up, you were a real aficionado of both comic books and newspaper strips.

SCHULZ: Gee, I used to buy every comic book that used to come out; I bought every Big/Little book that came out. I got the first copy of Famous Funnies. Some friend tore the cover off once. I lost a lot of things in a fire that took place in a big apartment building where my Dad lived. I had a big box of Big/Little books that was stored down in the basement in some storeroom. Lost them all. The fire department came in and flooded the basement. So I have no idea what things I even used to have.

GROTH: I know that you were a big fan of comic books, but you never seemed interested in being a comic book artist as opposed to a gag panel artist or a strip cartoonist.

SCHULZ: Yeah, yeah. In fact, we have to skip all the early days, because they were strictly amateur days. Back before... it's almost as if your life goes in little sections. And I got almost no encouragement in school and high school. Drawing was almost looked down upon, and cartooning really was looked down upon. I can still remember, for some strange reason in the 7th grade, it had something to do with social studies, and the teacher, amazingly enough, brought political or editorial cartoons. She had a few people just monkey around with them. And I drew the best one, and she liked them. I don't know what she was going to do with them; maybe she was going to have them printed in some newspaper or something like that. But she actually took my cartoon and gave it to another kid in class, to have him go over the lines to make them darker. And I was appalled and insulted by this, but I didn't dare say anything. But, you know, what a dumb thing to do. [laughs] Sometimes teachers aren't very smart.

Anyway, that was my first inkling of any kind of encouragement. And then, when I got into high school, of course, high school was a total disaster for me. As was junior high school. I just failed everything. I hated the whole business. And in English once, I don't know if it was Shakespeare or what it was we were reading, but we had to do some kind of a project on what it was we were reading. And I remember thinking that I could make some drawings about this — and this may seem hard to believe, but I actually thought, "Well, this wouldn't be fair." Because the other kids in the class can't draw. So why should I take advantage of something I can do that they can't? So I didn't do it. And some other kid in the class made some nice watercolors. He must have made about ten of them, about the thing that we had been studying. And afterwards, the teacher — I don't know how she ever knew that I could draw — but she said, "Charles, why didn't you do something like that?" [laughter]

And I never explained why I didn't, either. But that was just another blow.

GROTH: You learned something there.

SCHULZ: Oh, I learned something- I learned a lot. I learned several lessons in school, very important lessons, too, along that line. Then, of course, my greatest triumph was that book of drawings of things in threes that was reprinted in Peanuts Jubilee. The teacher — I guess, you know about that — she held mine up as an example. Because I batted out that whole page in about five minutes while the other kids were struggling just making three or four drawings. All the way through school, I can remember I was, if not always the best, at least one of the two or three few that could draw reasonably well. I couldn't draw really well, but I could draw better than most people. I was the first kid to figure out how to draw a hole in the ice. Because in Minnesota, we always had to draw something that we did at Christmas vacation, we always drew kids skating. And everybody drew a hole in the ice with the sign that said "Danger" or something like that. But the kids didn't know how to draw a hole in the ice, they just made a black spot, but I was the first one to discover how to show some thickness ot the ice, because I had read it in cartoons and comic books, and the teacher looked at this one day, and she was amazed that I should've drawn something like that.

But then, when I was a senior, the teacher asked me one day to draw some cartoons of things around school, which I did, and I gave them to her. When the high school annual came out, I looked through it anxiously, and they hadn't printed them at all. That was a crushing blow. That was my first major rejection. During that period, I was taking the Art Instruction correspondence course, which was called Federal Schools. At that time, a salesman came out to the house one cold winter night. I can still remember him coming up on the cold storm-doored porch. So, we signed up for the course, which I think cost $160, and my dad had to pay for it at a rate of $10 a month. Even at that, he struggled to make the payments. But I didn't have anything to do after graduating. I would stay home and work on the correspondence course. I never always had the right materials to draw on, either. Paper was expensive. I would sometimes go downtown to St. Paul to a big art store, and I'd buy maybe two sheets of smooth-ply Strathmore. That's all I could afford. And I was experimenting with crafting double tones because of what Roy Crane was doing with it. But I could only afford maybe one sheet, because it cost 75 cents. And I could only get maybe three strips out of it. I rarely had good paper to work on. But I was always drawing something.

I used to draw a series of, like, Believe it or Not! panels, mostly about golf. I had become a golf fanatic, and I was drawing a lot of golf cartoons. Then, when I was a senior in high school, I was also a Sherlock Holmes fanatic, and I read every Sherlock Holmes story that was ever written. I would buy a scrapbook at the dime store. And I would draw my own Sherlock Holmes stories, filled this whole scrapbook, just like it were a big comics magazine. The only person who ever read it was a friend of mine who lived up the street and around the corner, named Shermy. Who was a violinist, and I'd go listen to him practice the violin now and then, and he would read my Sherlock Holmes stories. Nobody else ever read them.

So I filled up several books doing that. But in the meantime, I started to send in gag cartoons, mainly to Collier's and the Post, I suppose. Never sold any. My dad would take them for me in the morning to the Post Office, which was near the barber shop, with a stamped self-addressed envelope, and then they'd come back the next week. I was collecting a lot of rejection slips, never even coming close. But I studied gag cartooning very carefully. And one of my first jobs was working as a delivery boy for a direct mail advertising company in Minneapolis. And with one of my first paychecks, which was $14, I bought a collection of Collier's gag cartoons called Collier's Collects Its Wits. And I still have it. I used to read that book over and over and over, just loved looking at all the gag cartoons, and I can still remember some of the punchlines. So I was willing to be a gag cartoonist. I hadn't really decided what direction I was going to go. And I was also drawing comic strips of my own. And of course, I was a great Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy fan, and I would send things in and get them rejected.

I became fascinated by the Foreign Legion, too. I read everything about Beau Geste and the others that he had written. And I used to draw Foreign Legion strips. And then, lo and behold- I might still have been in high school, I'm not sure — my mother had read in the papers something about a cartooning class downtown in St. Paul in a great big building which was an extension of the University of Minnesota. So I went down, and I signed up for it. There was a young man teaching the class who had a small comic strip running in our local paper. And he was pretty good, a very nice fellow, and so I signed up for it, and he told us what equipment to bring the next week; we had to bring a drawing board, and some ink, and some pencils, and pens... So the first night there he had some large pieces of paper tacked to the wall. And I distinctly remember that one of them was Dagwood, and I don't remember what the other characters were. But he just asked each of us to copy these characters. I suppose it was a good idea just to see what level of ability each one of us had. And of course, I was used to drawing those things, because I had drawn and copied those comic characters all my life. So I just went through them like nothing. And I was done in a matter of about four or five minutes. Way ahead of everybody else. Much better than everybody else. But there was the prettiest little girl I had ever seen sitting two chairs away from me. And I wanted so much to talk to her, but there was some idiot little kid there who kept drawing Bugs Bunny and saying that it was his character. And I'd get so mad at this kid because he had the nerve to talk to her, and I didn't. And I never did talk to her. I just didn't have the nerve.

But one time, he wanted us to each start a special project, and I had drawn a Foreign Legion comic strip. And of course, having the correspondence school background, I had learned to letter very neatly and render neatly, and he showed it to her. I can still remember--isn't that something? Something that happened so many years ago — and I can remember sitting there, and he showed it to her, and she looked at it, and said, "Oh, that's so neat." [laughs] I was so flattered, but I still didn't have the nerve to talk to her.

GROTH: You would have been around 16 or 17.

SCHULZ: I would have been 17, I guess. Six years later, I had a date with her. Isn't that astounding? [laughter] After the war.

GROTH: Congratulations.

SCHULZ: Now she's dead. Now she's dead, and it saddens me terribly. But anyway, that was the struggle I was going through, all before the War. And then the war came along, and I remembered going up ot the service club one Sunday afternoon, as we used to do if we had some time of, just ot have a good lunch and dinner, and upstairs in one of the rooms, they had an exhibition this one week of original gag cartoons from different magazines. And I stood there, and walked around the room, and looked at them, and I was admiring so much the quality of the drawing and the rendering of these things, and I was thinking, "When in the world am I ever going to get a chance to do this?" The War is still going on, and none of us knew if we were going to return. It was so depressing. [laughs]

But after the War… I never got to do anything during the War. I knew wasn't that good, and never even tried to send in things to Yank Magazine or Stars and Stripes or anything like that. But after the War, I returned home, and my Dad and I lived in this apartment with a couple of waitresses who worked in the restaurant nearby. We shared the apartment with them. I went over to Art Instruction in Minneapolis and showed some of my work to Frank Wing, who was a wonderful cartoonist of his day. A man named Charles Bartholomew was the head of the cartooning part of the school, and he offered me a job as a temporary replacement for one of the other men who was going on a two-week summer vacation. So I took it. There were about 10 of us in the room there. And then they ended up keeping me on permanently. And so that was the start of a whole new life. Because I was then in a room with people who were very bright and had a lot of ability in many different directions. A couple of them had been commercial artists: Frank Wing was a good cartoonist; Walter J. Wilweding was in charge of the department. He was a fine animal painter. There was a woman named Mrs. Angelikas, who was a practicing fashion artist. She did men's fashions several times a week for the local paper. She was very good. They were all quite cultured. They were all well-read, they all listened to good music. It was a good atmosphere. It was a lot like working for a newspaper, but not quite as hectic. And so I learned a lot being with them, and while I was with them, I had the chance in my off-time to work on some of my own things.

And you mentioned comic magazines. I actually drew three pages of different comic magazine samples. One was a war episode of some men in a half-track, which was autobiographical. Another one was some little characters I called Brownies, who were just cute little fanciful things, and then another jungle type freelance work like this, and that all of their work was done by hired people in New York.

I was still going around trying to get jobs. One day, I was sent to downtown St. Paul to a Catholic comics magazine. They did Catholic Digest and some other things. I took the comic strips that I had, and a man named Roman Baltes looked at 'em and said, "Well, I think I may have something for you. I like your lettering." So I was assigned to write the entire comics magazine. He had three or four men who were already there on the staff. Somebody else would write stories, and they would illustrate them. Apparently, they didn't have anybody who could letter comic strips very well so they would give me the original pages, and I would take them home at night and letter all the pages. Sometimes they would give me a French or a Spanish translation, and I would have to letter the whole thing on some kind of see-through paper in these other languages. I never thought of it as being hard work, even though I was doing it in the evening after having spent the day at the correspondence school. I would do these things, and Roman liked the fact that could do them fast. Sometimes he'd call up in the late afternoon, and say, "Sparky, I've got five pages here, I'd sure like to have them done tomorrow morning." So I would either take the streetcar or my Dad's car and drive downtown. He'd leave them outside the office. I'd pick them up, take them home, sit in the kitchen, and letter them. The next morning, I'd get up early, drive downtown, leave them outside his office and then go on to the correspondence school. Now that may sound like Abraham Lincoln, but to me, it was what I wanted to do.

And so I became very good at lettering. I could letter very fast. I got so I didn't need guidelines or spacing or anything.

That was good training for me.

GROTH: Can I ask you about ten questions based on what you've said so far?

SCHULZ: Please.

GROTH: You mentioned going to the correspondence school and meeting all of these people who were involved in music and art and so on. Would you say that they represented an opening up of your world? Did that environment invigorate your curiosity about art? Was this an atmosphere you hadn't really experienced as fully before?

SCHULZ: Oh, definitely. It was almost better than going to art school. Now, most of my friends either went or graduated from the Minneapolis School of Art. Which was a fine establishment. And that was one of the first things that I did when I came back from the War — I knew that under the G.I. Bill, perhaps I could finally go to a residential art school and take some actual, on-the-spot training. So I went there, and I made a few drawings, which you had to make just to demonstrate if you had any talent. Unfortunately, the administrator there said that I was about two weeks too late. The classes had already started. But then she said, "We do have some night classes, if you'd like to do something like that." So I signed up for a life sketching class. And I did that for one semester. I wasn't especially good at it. But that was the first real live training I had had.

So, I never really did go to the Minneapolis School of Art. That was about it. The next semester I signed up for another class in just drawing. But I missed two or three classes because I had these other lettering jobs to do. And then I was told that under the G.I. Bill, if you missed three classes, you were out. So that was the end of my training.

GROTH: Was that disappointing to you?

SCHULZ: No, not really. I knew what I wanted to do. But this Art Instruction group of instructors created an invigorating atmosphere. There were always lots of live conversations going on as the people were sitting at their desks: some dictating responses; others, just making corrections.

The only problem became a social problem in that, the same time, I still loved golf, and had three or four friends with whom I used to caddy and play golf. So, on Saturdays, sometimes Sunday afternoons, we would play golf. So that was one group of friends. Then there was a group of friends at the correspondence school, and I became very close with many of them, and that was the second group. And then at this same time, I also became very active in the Church of God movement. I went to a prayer meeting one night — we had some nice discussions— and went to what they called a young people's meeting, and enjoyed the discussions. They were very nice people. Now, that put me in three different social groups, and they didn't overlap. They didn't meet. I was never able to solve that.

GROTH: You were never able to reconcile — or integrate these different social strata?

SCHULZ: I was never able to find the right people in these things, so I could concentrate on that. That caused me a lot of trouble.

GROTH: In what way?

SCHULZ: Well, in… say if I liked a certain girl, for instance, maybe she was with the correspondence school, but then I didn't have any girlfriends in the church group. And of course, the golf kids were foreign completely to church and art and cartooning. So nothing worked. [laughs]

GROTH: They didn't connect.

SCHULZ: Nothing connected. That made it very awkward.

GROTH: It sounds like you sort of blossomed about this time. You've talked a lot about how shy you were as a kid and how you weren't really socially acclimated, but it appears as though you started traveling among three different social settings; it almost looks like you turned into a bit of a social gadabout. [laughter]

SCHULZ: I think shyness is an illusion. I think stupidity is a better reason. I think shyness is the overtly self-conscious, thinking that you're the only person in the world. That how you look and what you do is of any importance. Not realizing if you just get out and do something and talk to people, you don't have to be shy. It's just being overly self-conscious.

GROTH: You said that when you were in high school, cartooning was looked down upon. And I wonder if you had a theory as to why that was. Was there a kind of middle-class propriety involved, where cartooning was considered disreputable...?

SCHULZ: I think it was the teachers' fault. I think... music teachers were the worst of all. Music teachers were the meanest. Art teachers were always pretty nice. But they weren't capable of either doing cartooning themselves or even appreciating it. And they had to bring the whole class down to the lowest denominator. Because these weren't kids that, especially, were going to be artists, or even interested in it, but they had to create projects that would interest the whole class. So you ended up having to make posters or doing watercolors of flowers or silly things like that, which just drove me out of my mind. [laughs] You never got to do any drawing; it was always some kind of project. Even linoleum cutting- which I never got into. I was glad I never had to do that. But as far as drawing goes, we rarely got to do any real drawing. It just had to have been the teacher's fault.

IN THE ARMY

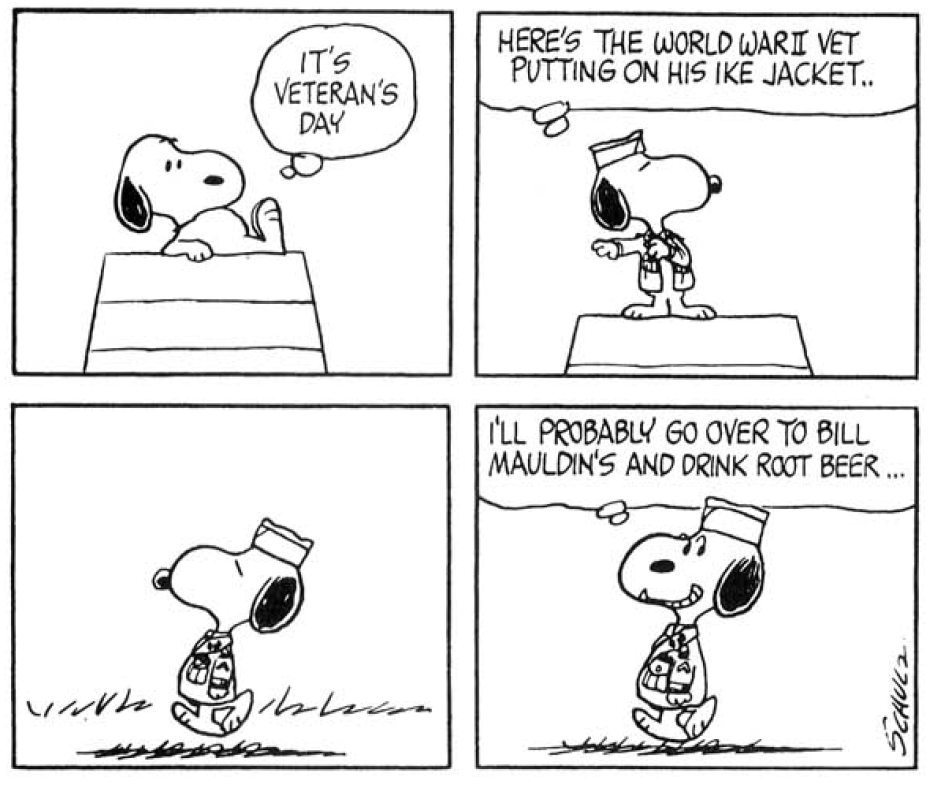

GROTH: You referred to your stint in the army, and I think you said you didn't do much drawing in the army. You once said, "I just wasn't ready, and I think Bill Mauldin's work made me realize it." You also said, "The truth is I abandoned drawing during my years of service." Was looking at Mauldin's work intimidating — you felt you were unprepared?

SCHULZ: It wasn't intimidating. I just wasn't even close to being able to do it. Plus the fact that after a while, we worked very hard at being good soldiers. I have never been away from home. Not knowing what it would be like to live with 200 men in the same building. And I can remember the first time I sat next to a water-cooled machine gun and heard that thing fire. Oh, man, it was loud and shocking. And then the first time we had to dismantle a light machine gun thought, "I'll never learn how to do this." I had no mechanical ability. I had never seen a gun in my life.

But as the months went by, and as we developed more in our training, and went on maneuvers and all that, I finally got to be squad leader of a light machine gun squad. We all worked very hard at being good soldiers. And we took great pride in being in the infantry. We were in the armored infantry. And to me at that point, even though I still loved cartooning and drawing, and I carried a sketchbook where I made some drawings of friends, I was still very interested in being a good infantryman. We were very proud of what we were.

Which is good, because I look back on it with some hateful memories, but also wonderful memories of the friends we made, and the good guys I knew, and all of that. Proud of the fact that we did what we had to do. Somebody asked me just a couple months ago, of all the awards you've received, what award are you the most proud of, and all of a sudden it occurred to me: the combat infantry badge. Which is over there on the wall. I'm more proud of having received the combat infantry badge than of having won the Reuben twice. [laughs]

GROTH: Can I establish a context for your war experience? You were drafted in the army in 1943. Were you aware of what was at risk in that war, what you were fighting for?

SCHULZ: Oh yeah. Definitely.

GROTH: Weren't you present at the liberation of one of the concentration camps?

SCHULZ: No… not... quite.

We spent the night out in a field — I don't remember if it was raining, but it was awfully cold and misty that night. I think there was a big swamp out in front of us. They said that we had to be ready because there may be a counter-attack by the SS. But it never happened. So the next morning, soon as the sun came up, we moved out. And then, that day, they told us that Dachau had been discovered. Part of our division was in on that. But we had gone on towards Munich. So we never saw it ourselves. But at least we were there.

GROTH: Now, correct me if I'm wrong, but it seems that prior to your going into the army, you led a pretty sheltered life with your family in the city of St. Paul, so going to war must have been a tremendous, an almost inconceivable break from that kind of life.

SCHULZ: It was. It was a terrible experience.

GROTH: You referred earlier to hateful memories.

SCHULZ: Well, just being in the army was such a desperate feeling so often. Of loneliness, and of the fear that it was never going to end. We used to sit sometimes in the evening talking, and we'd say, "They're never going to let us out. We're in this for the rest of our lives. Where's it all going to end?" It was so depressing.

But I did make a lot of really good friends. Unfortunately, many of them have died. However, my best friend is still alive. He's 85 years old now. He was our mortar squad leader, and I was a machine gun squad leader. He was like a big brother to me. He really kept me going.

But I suppose... You know, the whole world was at war. It was something that had never happened before, and undoubtedly, I think, will never happen again.

GROTH: When you came home from the war, did you feel transformed?

SCHULZ: I felt good. [laughter]

GROTH: But was going through that a transformative experience?

SCHULZ: Yes... It was... I came home on the train. I don't know where I got discharged, from what camp it was. A duffel bag on my shoulder, the streetcar pulled up in front of my dad's barber shop. I put the duffel bag on my shoulder and got out of the back of the streetcar. I walked around, crossed the street, into the barber shop. He was working on a customer. [laughter]

That was my homecoming. There was no party. Nothing.

GROTH: A little anticlimactic.

SCHULZ: Yes, it was. I look back on it, and I think, "Well, that was robbery. I didn't get to be in a parade, no one gave me a hug, or anything like that." But I felt very good about myself those days. The other friends that I had that I golfed and caddied with were all coming home at the same time. None of us had any jobs. In those days, you could join what they called a 52-20. If you didn't have a job, the government gave you $20 a week for 52 weeks. So most of us belonged to the 52-20 club, at least for a few months. We played a lot of golf. We had an early spring in Minnesota at that time. It was kind of a carefree life for a while. My cousin had just come back from the Marines, and he and I used to go bowling. Different things like that.

I still had some relatives around that I was very close to. But that all gradually just fell apart, as everybody went finding their different directions.

GROTH: Was there a sense of post-War euphoria?

SCHULZ: No, not that I recall. Nobody even thought much about it.

WASTE OF TIME

GROTH: You once said, "The three years I spent in the army taught me all I need to know about loneliness."

SCHULZ: Yes.

GROTH: "And a sympathy for the loneliness that all of us experience was dropped heavily on poor Charlie Brown."

SCHULZ: Oh, it was terribly lonely in camp a lot of times, because you were just totally trapped. You just didn't want to be there. And I suppose I might have had an approaching agoraphobia, which I still suffer from to these days, in different degrees. Which made it even worse. But a lot of the truth has to do with maturity and immaturity. If a person were totally mature and had a good outlook on life, he could make good use of experiences like that. You could have gotten a weekend pass and gone into town, done some sightseeing, or met some people. There's a thousand things you could have done. But when you're 20 years old, how do you know that? So you're not able to make use of it.

GROTH: Although you made use of it later by transforming that intense feeling of loneliness into art.

SCHULZ: [laughs] Yeah, yeah. [pause] What a waste of time. [laughs]

GROTH: How do you mean?

SCHULZ: To spend all of your life drawing your comic.

GROTH: You don't really mean that, do you?

SCHULZ: Sure.

GROTH: How do you mean that? I would think you feel exactly the opposite.

SCHULZ: Well, you know: what have you done? Drawn a comic strip. Who cares? [laughs] Now I'm 75 years old.

GROTH: But don't you feel like you have an enormous achievement behind you, a lasting legacy because of that achievement?

SCHULZ: No. [laughs] Because I know that I am not Andrew Wyeth. And I will never be Andrew Wyeth. But the only thing I'm proud of is that I think I've done the best with what ability I have. I haven't wasted my ability. A lot of people wasted their ability, their talents; they don't know how to do with what they have. I'm pleased with what I have done. I haven't destroyed it, I haven't misused it in any way.

GROTH: Let me try and nail you down on that, because you must be very proud of what you've done. You must know you've reached the pinnacle of your profession.

SCHULZ: I know, it's hard to believe. I'm amazed when I read Cartoonist PROfiles and other magazines where young cartoonists are interviewed, and they mention my name as being one of their inspirations. That just astounds me.

GROTH: Why should it?

SCHULZ: I don't know what it was that inspired them. I have no idea. Except that I took a unique approach as the strip developed. I think I did things that no one else had ever done.

GROTH: If I may say so, I think it's because you conveyed the depth of your humanity in the comic strip. And that's a relatively rare phenomenon in cartooning.

SCHULZ: You do some things that it's better you don't think about. [laughs] You can dig your own grave by thinking you're better than you really are.

The post Charles Schulz at 3 O’Clock in the morning: An excerpt from The Comics Journal #200 interview appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment