Lee Lai’s Stone Fruit and Cannon both tell complicated stories about family and identity. Stone Fruit is the story of a woman dealing with the slow disintegration of her relationship with her partner, and her attempts to pick her life back up and help raise her niece through her depression. Cannon is about a perpetually unflappable woman whose work, family, and friendships all choose the same moment to fall apart. (The Atlantic calls the book, “a raw depiction of what panic feels like.”)

They are some of the best graphic novels of the past five years, exploring contemporary queer life while capturing the emotions of living through the 2020s. It’s not just me who thinks so: Stone Fruit won the Lambda Literary Award for Graphic Novel, the Cartoonist Studio Prize, the Lynd Ward Graphic Novel Prize, and two Ignatz Awards, and she was selected as one of the National Book Foundations 5 Under 35. An Australian cartoonist living in Tio’tia:ke (Montreal, Canada), Lai’s comics have been featured in The New Yorker, McSweeney’s, The New York Times, Granta Magazine, and the Museum of Modern Art Magazine.

In this interview, Lai talks to TCJ’s Gina Gagliano about her graphic novels: and queerness, invisible magpies, kitchens, and bicycles.

In your first graphic novel Stone Fruit, I love how your characters are monsters when engaging in creative play with kids — they just transform into whole new selves. Can you talk about where those depictions came from?

The relationship between Nessie and her aunties was developed in a series of short comics I made over a year before I wrote the script for Stone Fruit. In one of those shorts, I drew out a scene where the three of them turn into monsters to devour a rotisserie chicken. I thought it did a thing I was trying for: showing the abandon and silliness that play-pretend games are so good at getting us into. That, and it was fun to draw, so I kept the transformations for the book.

The scene in Stone Fruit where Amanda is talking about how a huge part of parenting and caretaking is just showing up is wonderful. Can you talk more about that?

Thanks! I’m glad it landed.

That was an attempt to contrast some of the more idealized, politicized rhetoric about community and caretaking I’ve often encountered in queer spaces, with the lived-in pragmatism of a thoroughly unromantic (and occasionally uncritical) person who’s just getting through her day. I was "raised" in queer spaces that have always had a lot to say about community as a concept. Watching the nuts-and-bolts of that play out — beautifully, ungracefully, often with much drama and contradictions — has been a fascinating and ongoing journey for me and my peers.

A lot of this book is a story of a relationship that doesn't work out. Why did that topic interest you?

All the queer media I grew up with was about the process of coming out, often facilitated by the budding of a new relationship. Only well into my twenties did I come to appreciate how breakups are also a huge part of the social fabric of the queer world, and so I wanted to write a story that reflected that. It was important for me too to try and show a relationship fraying apart despite both parties’ best efforts. I was shocked and humbled to learn in my young adulthood that all kinds of relationships can fail despite one’s best efforts, and this book reflects that particular coming-of-age for me (and the characters!).

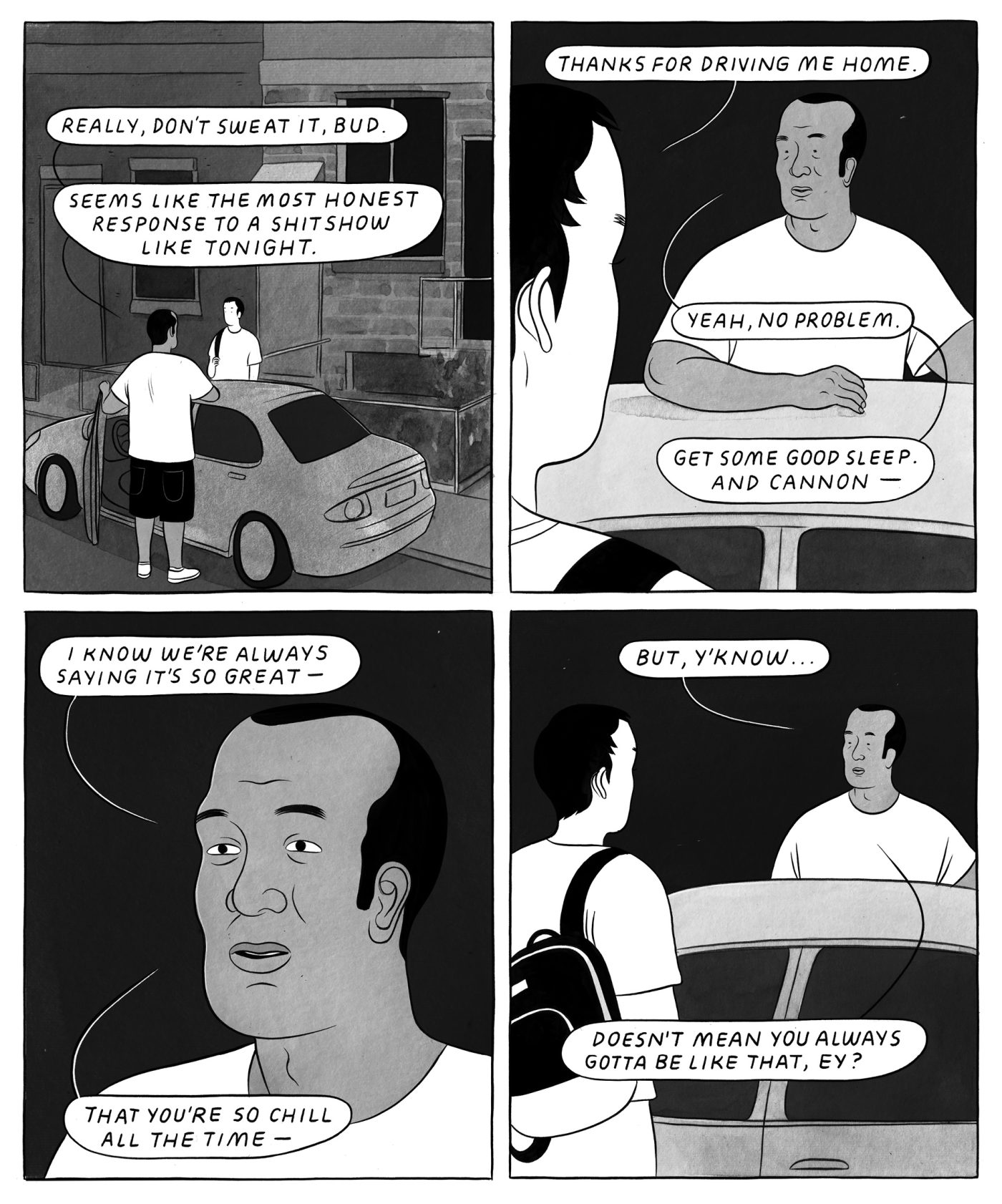

In your new graphic novel Cannon, the protagonist and title character Cannon clearly thinks of herself in the box of "the sensible and reliable one" in her and Trish's friendship, at her job, with her family. Can you talk about the kind of pressure that label has, and why you were interested in writing that kind of character?

I wanted to depict the more predictable, filial circumstances that would shape Cannon’s personality as the reliable and stoic one: real necessity, a vulnerable and avoidant parent, chaotic and occasionally oblivious friends. But a harder challenge, especially through only dialogue, was to try and suggest at least some of the ways Cannon might find that role satisfying from a place of ego.

I was really grateful to Australian journalist Declan Fry for remarking on the theme of vanity, when he was writing a review of the book. I’ve been challenged at times by loved ones for my dogged attachment to being patient and long suffering, even at the expense of honesty, integrity or sanity. There’s something suspiciously righteous in that placement. So I enjoyed putting Cannon in the fast-lane for eating some of the harder lessons connected to that role, ideally without concluding that the problems she’s facing are all of her own making.

Why did you choose a restaurant as the setting for a lot of this book?

I worked in cafes and restaurants until I started freelancing comics full time in 2016, so there’s a lot of fun personal experience to inject into that setting for me. Plus, it felt like a good setting with the aim of the game being to ratchet up the pressure on Cannon in a short period of time.

Sexual harassment of women working in restaurants is pervasive (NPR says that 70% of women working in restaurants have been harassed!). Cannon and Jacinta are both dealing with this in different ways throughout the book — I'd love to hear about why you wanted to write about this.

Kitchens are a boys' world! And then working front of house opens one to a different kind of harassment. Gender plays out in such extreme ways in the service industry and there’s some deep masculinity shit embedded in kitchen culture in particular. I wrote it into this story because I’ve yet to find a food-based business untouched by it.

I'm really fascinated by the way you accumulate problems for Cannon until she can't take it anymore. At the point she's destroying the restaurant she works at, I'm totally there with her! Can you talk about that sense of the weight of so many rotten things all stacking up that you're writing about? I feel like that's something a lot of people are feeling about life today! The book's back cover copy calls this scene "a nervous breakdown" while I (and Cannon's fellow restaurant employees) are like "this is very reasonable." What do you think?

I’m glad you think it’s reasonable, to an extent I do as well!

I came across a refreshing thought-piece online a while back — if only I could remember the source — that critiqued wellness culture’s emphasis on individual efforts to self-soothe and regulate, without naming the wildly unjust and unregulated social circumstances that are contributing so heavily to our distresses in the first place. It’s not as if I don’t love a coping mechanism or three, but over the period of writing this book I’ve developed a growing fondness for confrontation. Particularly in relation to utterly unworkable situations — whether that be in a small-scale social world, or our global response to a genocide.

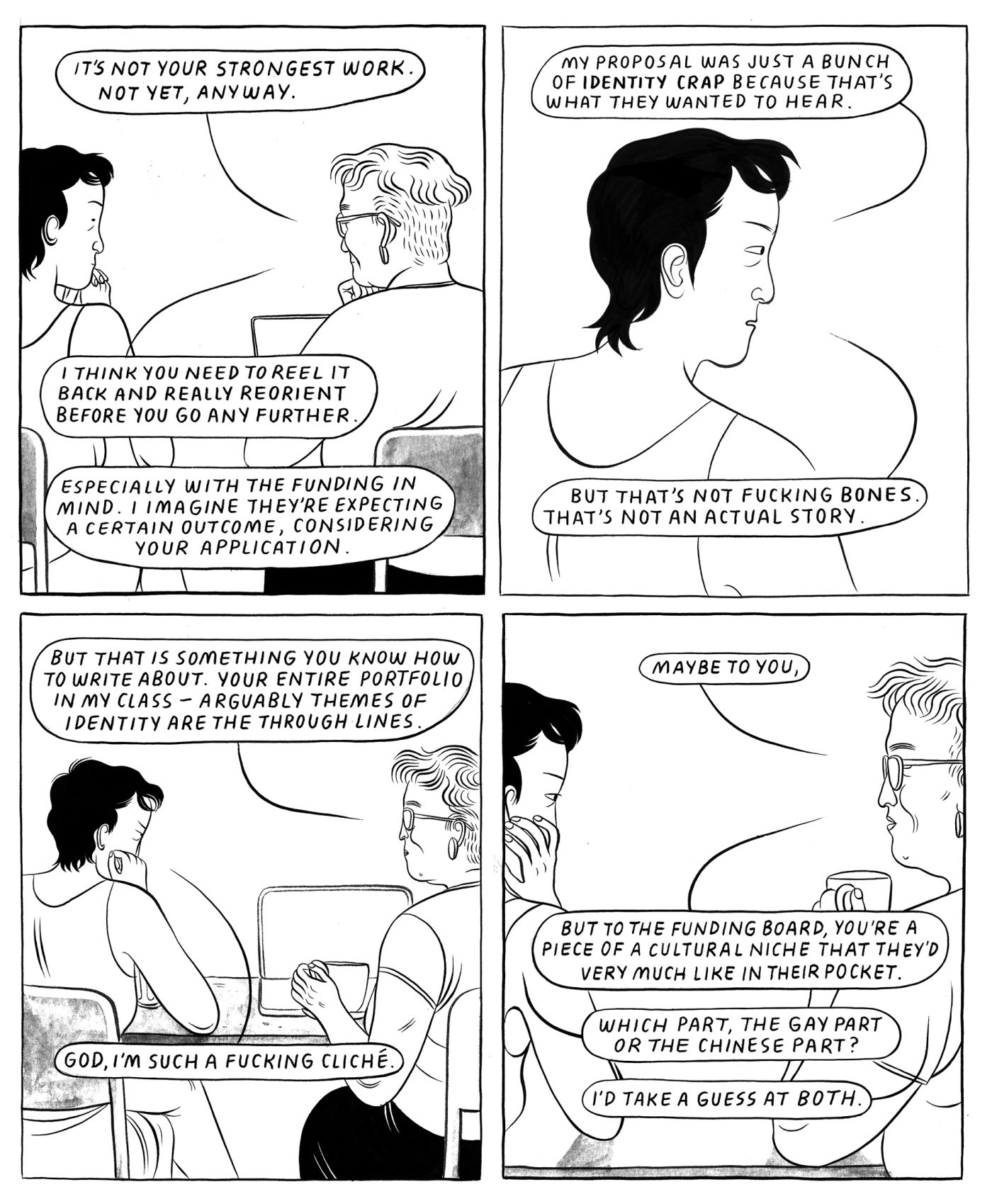

At one point in your book, Trish talks about being a queer person of color and struggling with the fact that the people who give grants and publishing contracts and awards are looking for identity-based narratives about those specific parts of her life. Can you talk about that? I'm curious about your thoughts especially since you are a queer person of color writing a book about many topics that seem like they could be personal to you — queerness, family, friendship.

That piece of the story was my desire to have the reader feel as self-conscious as I do, at times, about the way that certain identities are consumed in the cultural sector. I could write an essay on the tricky nuances and choices to be made when writing (and fictionalizing) personal stories that I know will then be consumed as “xyz marginalized experience,” but for the sake of brevity: writing characters that aren’t explaining themselves or their experiences is a priority for me. From a writing perspective, I think it makes for a genuinely more interesting character, but it also makes me feel like I’m not exploiting my characters (or myself, in the moments when their experiences intersect with my own).

This book is mostly black and white, but there are bits of it in red — horror movies, getting really angry, flashbacks — can you talk about your use of color?

The limited use of red color spots was a fun thing to play with. One thing I’ve grown to love in horror films is the extremity and silliness of them — something I think is actually often present in a lot of moments of rage. For better or worse, I think when people reach a certain level of fury, things get really loopy and unhinged, even comical. I wanted a visual through-line to pull these moods/moments a bit closer together.

There are bits of French and Cantonese in this book, and from your author's note I learned that you were learning those two languages as you wrote the book. Can you talk about your process of language-learning, and about how you incorporated the two languages into your writing?

From a learning perspective, putting French and Cantonese in the story was a good challenge. Ironically, the Chinese had to be written in characters to be understood by native speakers, while my classmates and I were learning the romanized jyutping system. I ended up getting a lot of support from loved ones more adept in the languages than me, particularly my father for the Cantonese and my partner for the French. I’m not sure it would’ve been possible to build as plausible a story and setting without either language.

I just read Boum's Jellyfish, and I was delighted to see only-perceptible-by-the-protagonist animals in your book too. Can you talk about the magpies in Cannon?

Boum is such a great cartoonist! And animals are a fun storytelling tool.

At the risk of being cheesy, the magpies presented a lot of opportunities because of the breadth of interpretations: they’re often an ill omen in western traditions, and one of good fortune in an eastern context. In this story, they show up in moments that warrant anger — given what we both said before about appropriate levels of confrontation, the birds could easily be either an ominous or a welcome sign.

Do you have a favorite horror movie? I'd love to hear what you like about horror movies in general.

I used to be too much of a scaredy cat for horror, but friends have slowly grown my appreciation for the genre. Get Out was my first real “aha” moment for why the genre is so great: it’s so damn funny and smart and I feel like the adrenaline of the scares prime me so well to think deeper about the messaging. I’ve been catching up on older horrors since.

Families are so complicated! I feel like every time I read one of your books, there are even more ways that families can be complicated. Can you talk about why writing about complicated families is interesting for you?

I imagine that the reason I'm drawn to family dramas is similar to how I end up drawing with certain stylistic quirks — it’s just what I end up leaning into.

My own family is plenty complicated, but ultimately I’ve yet to meet a family that isn’t, and that’s part of the intrigue. The fact that families can be such a hot-pot of different personalities all smashed together makes things particularly interesting to me, from both an emotional and storytelling perspective.

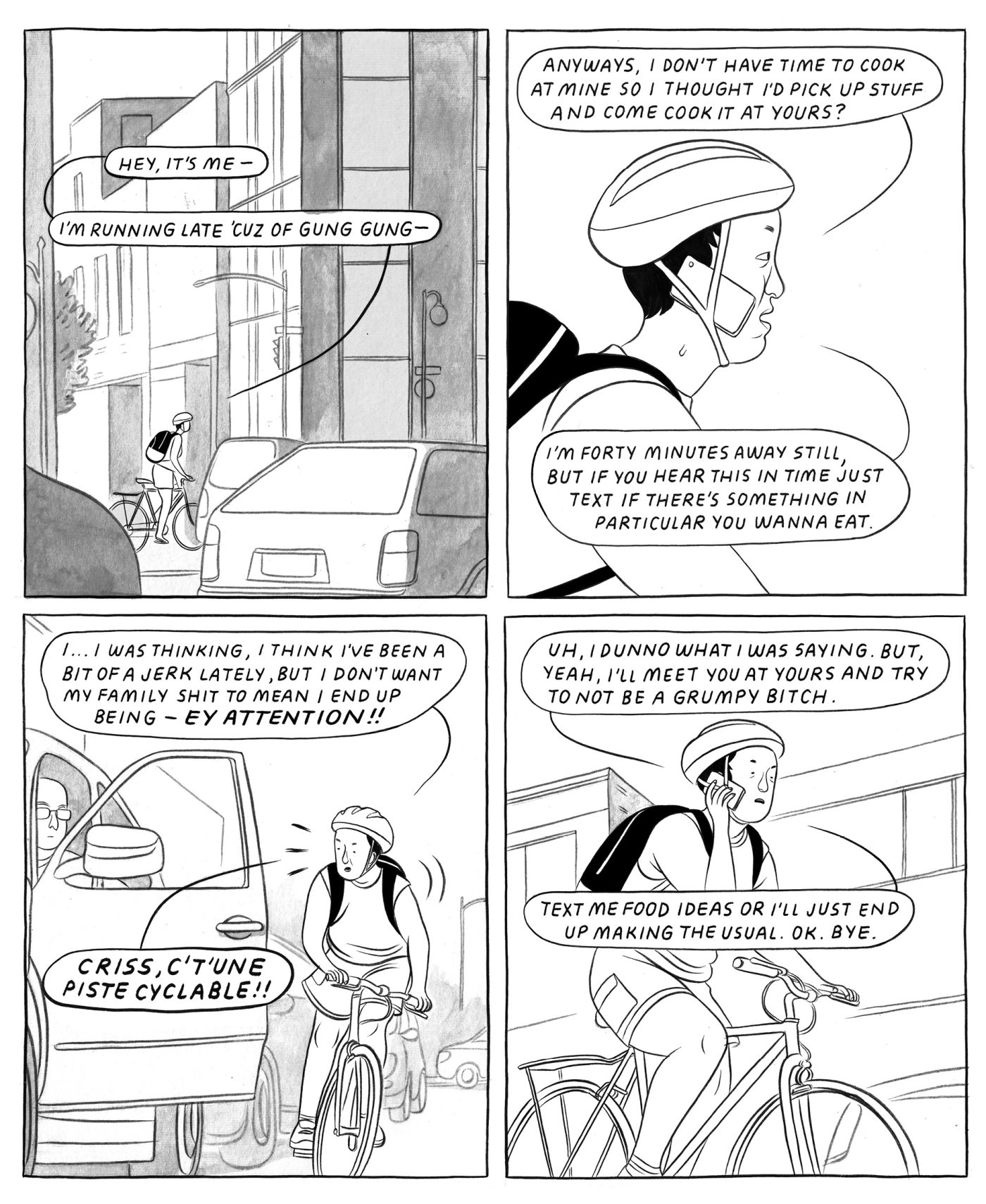

I want to talk a little about bicycles, because you have many bicycling characters in your books. Do you bicycle yourself?

I love to bike, and I think cycling is an especially big part of the urban (and queer) culture here [in Montreal]. Like cooking, gay sex and certain kinds of physical behavior in the figures I’m drawing, I think it boils down to what I like looking at and therefore want to replicate!

What's next for you?

I’m working on a few projects at once, but the priority is to give myself a little break from long form and have a bit of fun with some short form. There’s a handful of things I’d like to experiment with in writing, and it’s been several years since I got to play with short fiction. I’m particularly excited to collaborate with two local writers, both friends whose work I admire: francesca ekwuyasi (Butter Honey Pig Bread, 2020) and H Felix Chau Bradley (Personal Attention Roleplay, 2021). I’ve also got a renewed interest in maybe developing a strip, particularly encouraged by touring recently with Tom Gauld, who is just a master at the gentle, dry funnies.

What are you reading now?

I’ve just finished reading Stag Dance by Torrey Peters, which has really fed my excitement for shorter fiction at the moment. Also Omar El Akkad’s One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This which is one of the best, most thoughtful condemnations of western liberalism I’ve encountered in a while. Required reading for this particularly existential moment, especially for creatives.

The post An interview with Lee Lai: ‘I’ve developed a growing fondness for confrontation’ appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment