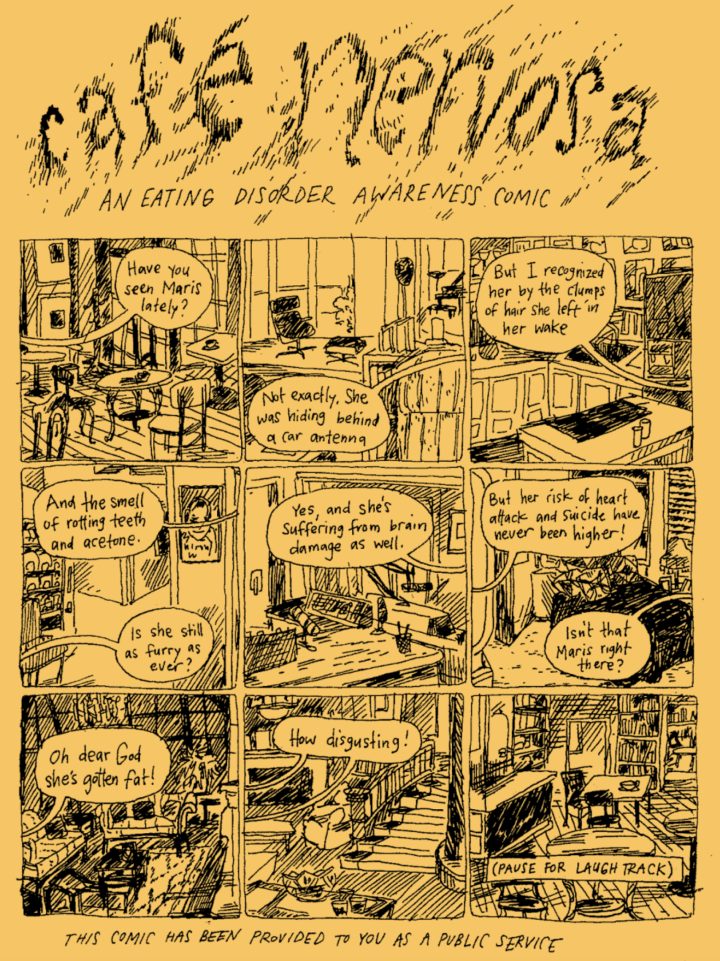

Julia Gfrörer is perfectly capable of flawless rhetoric, as proven in the second of two Frasier parodies within World Within the World. She shows us a series of panels of environment furniture behind a conversation between two unseen characters about Maris, also unseen; the perfect hypocrisy of their judgemental framing is crystalline, sending hard glints of light into the eye quite unexpectedly. In this way it differs from the majority of the works within the book, because it’s whole and fully calibrated for balance. But in this way too it’s just the same, because it is inarguable.

Gfrörer has this and more in common with Moto Hagio, also published in reprint by Fantagraphics, though they each produce original work for different markets within different national industries and scenes. As a pairing, their hardback short story solo anthologies World Within the World (Grförer) and A Drunken Dream (Hagio) are violent—as storytellers, they are violent, though neither produces what one would term loud comics, in the boisterous sense. The violence inside them isn’t “great,” like statues of Victorian war. Hagio’s is tragic (gasping) and Gfrörer’s is base: there are surface differences between their work, and there are substantial ones, but these only add texture to their similarity, and their similarity produces a resonance.

Moral certainty is not so didactic as perhaps it sounds. Neither are saying 'you must be like this in order to be Good'; 'you must not do that, or you are Bad'. Hagio’s shorts here bend more to rhetoric than Gfrörer’s, exception noted above, but of the kind that allows you to understand perspectives rather than the overtly influential. The moral certainty of these comics is the commitment to pain and wrongness. This sounds simple. But it leads both careers to investigate scenarios of incest and child abuse; it leads both to deeply consider isolation as a matter of choices and results, bargains and wounds. They deal with compromise in order to express what is uncompromising; they show wickedness, dismay and disaster in terms that allow us simply to perceive that “wickedness” and “dismay” and “disaster” are not just words, but expressions of meaning. People have been victimised, are victimised, tortured, punished, more—and each of those is a word that exists because it pertains to the experience—the experience being more than just a word. Certainty is internal—it’s actual—the mood that came upon me after reading both in close quarters was that the truest meaning of an experience is just what is happening to you, when it’s happening—and that includes the echoes. In fact the word I’m looking for to describe the shared tenor of their work is inextractable: they create an inextractable sense. People can treat you any kind of way, but the moral certainty of Gfrörer and Hagio as cartoonists is that those people can’t extract what YOU know about it when they do. They can’t destroy or overwrite it because it happens. And if it’s wrong that they’re doing, ain’t it wrong? Moral certainty means that that means something. Certainty is a silent rebellion. It’s actuality. It need not be didactic, because it’s there. The cartoonist need write no further than she does because she’s shown the nature of the issue. Each of these cartoonists is progressive in obvious social aspects but more relevantly each is progressive in that their work moves us through.

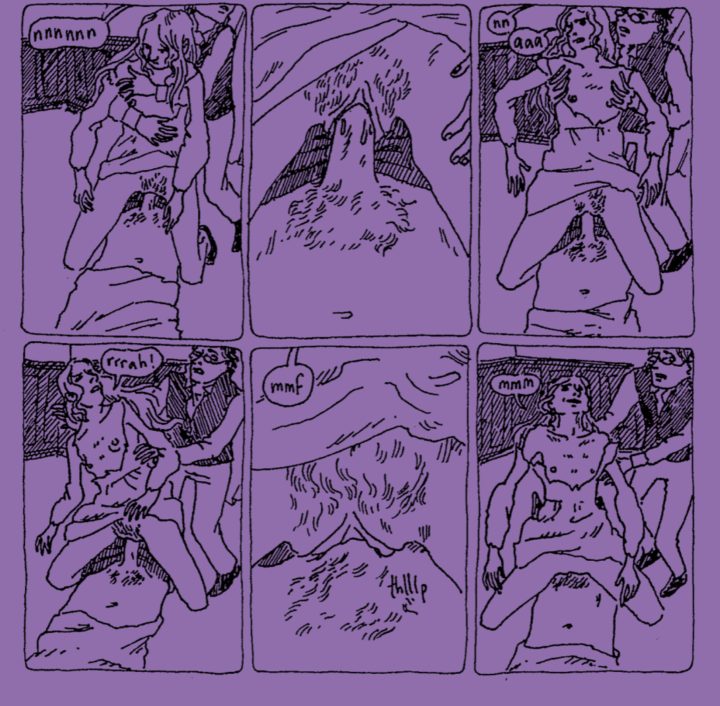

Gfrörer, working overtly for adults, is able to take her certainty into visible sexual congress and so we see the penis as a hot thing in this same incontrovertible way: not much beautified, not glamorised, but erotically compelling—factually so. The calibre of the men bearing them does not weigh on their attraction. One short shows us a coupling—incestuous and actively forbidden, witnessed as abhorrent, and fought by every participant in the scene. A woman, the sister, fights to fuck her brother. The brother fights inevitability because he wants to fuck her too. The onlooker, a minor authority of some kind, tries to haul the sister off the brother, making their disallowed tryst, in practice, a threesome. And I say “in practice” to express that his action morphs into sexual participation against his stated will, but that undercuts the scene, because both the sex and the added grappling from this man are evidently erotic. Arousal is a fact of the comic, it’s built into the narrative—she wants (in active intention and in pussy juice) to have sex, he is hard, she continues to pump and groan as a second man embraces and hauls her body back and forth during penetration. It’s a scene of sexuality and sexual contact, friction, lubrication, noise. Gfrörer has long been open that she makes comics that turn her on; on the page this scene isn’t ridiculous and it doesn’t compel shame. It isn’t hazy or gleaming; no cinematic tricks are borrowed here. It looks like any other page of any other Gfrörer comic, which is the heart of the matter: the story of sexuality is told, 'here’s what it’s like to want to fuck', and so it is erotic art. But does that mean it isn’t incest, that that can’t be a problem, that the outsize punishment of the couple previously having gone to the sister is irrelevant, that the second man shouldn’t have tried to stop her from fucking her brother…?

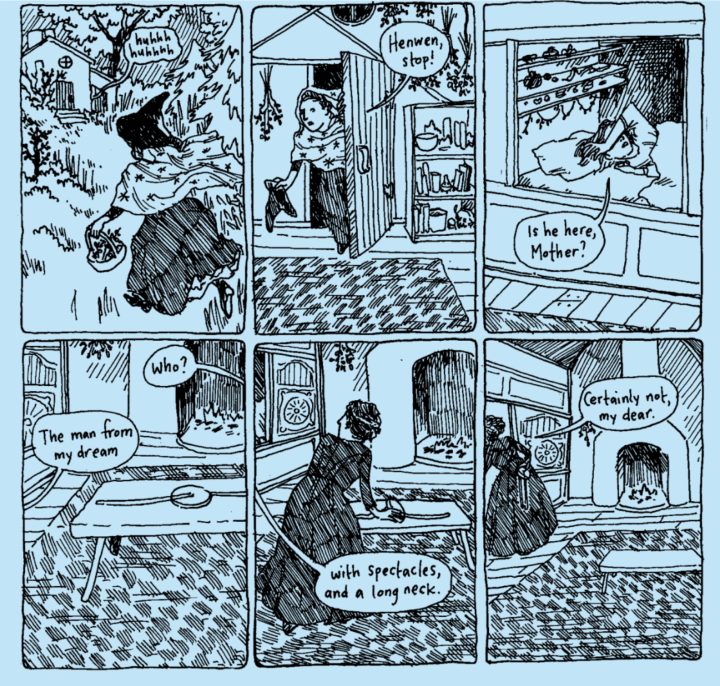

In a similarly-themed short, simpler to parse in the practical sense but almost more contentious, a witch-mother threatens away a man who was called by a spell her daughter, a child, cast for the summoning of a true lover. He knows he is looking for “her,” but he is not proud or happy to be told she is a child—Gfrörer is careful to fully problematise the problem, offering a dispassionate consideration of “the moral paedophile”—someone who is attracted to a child, a child who wants his attention as a lover, and the choice by the adult not to maintain any contact. If magic is real, he is what was called. But her mother knows that she’s a child, not ready for a lover. And the man knows that loving a child in this way would be appalling. If magic is real then he would be her fated lover, but the adults know that allowing that would be wrong. The end. She gives us the “best version” of this rhetorical scenario, and nothing more, dropping the story off like the majority of her shorts: suddenly, no uplift to hang a hat on, no further matters with which to distract the unsettled moral mind. It doesn’t feel like rhetoric because it doesn’t attempt to convince—no strong eye contact is maintained. Moral certainty doesn’t come from lack of challenge, but from awareness.

Within A Drunken Dream, Hagio doesn’t range into explicit sex and her eroticism is largely absent. One story about a student and her teacher becoming involved performs much the same for me as the last described Gfrörer short, despite the difference in tonal melodrama.

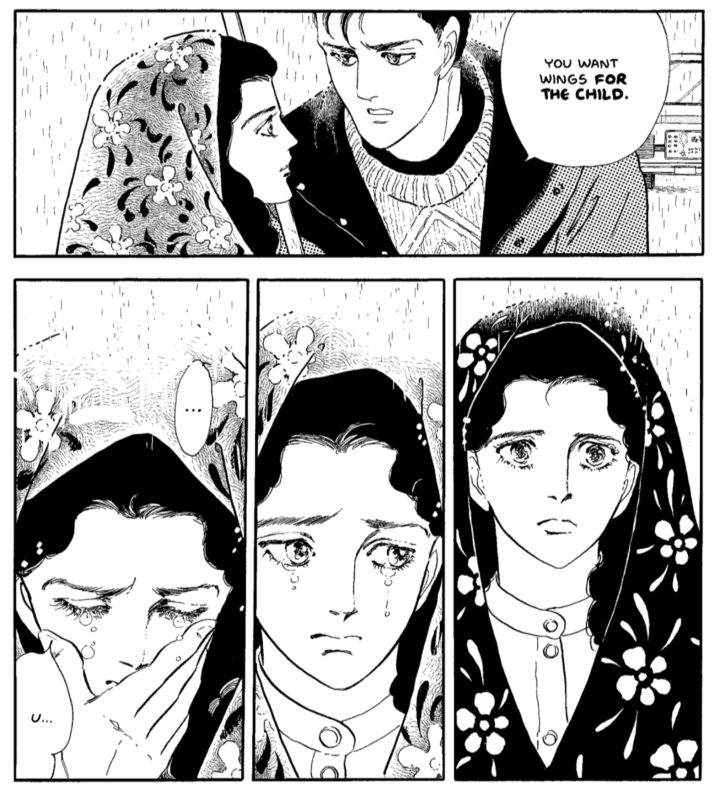

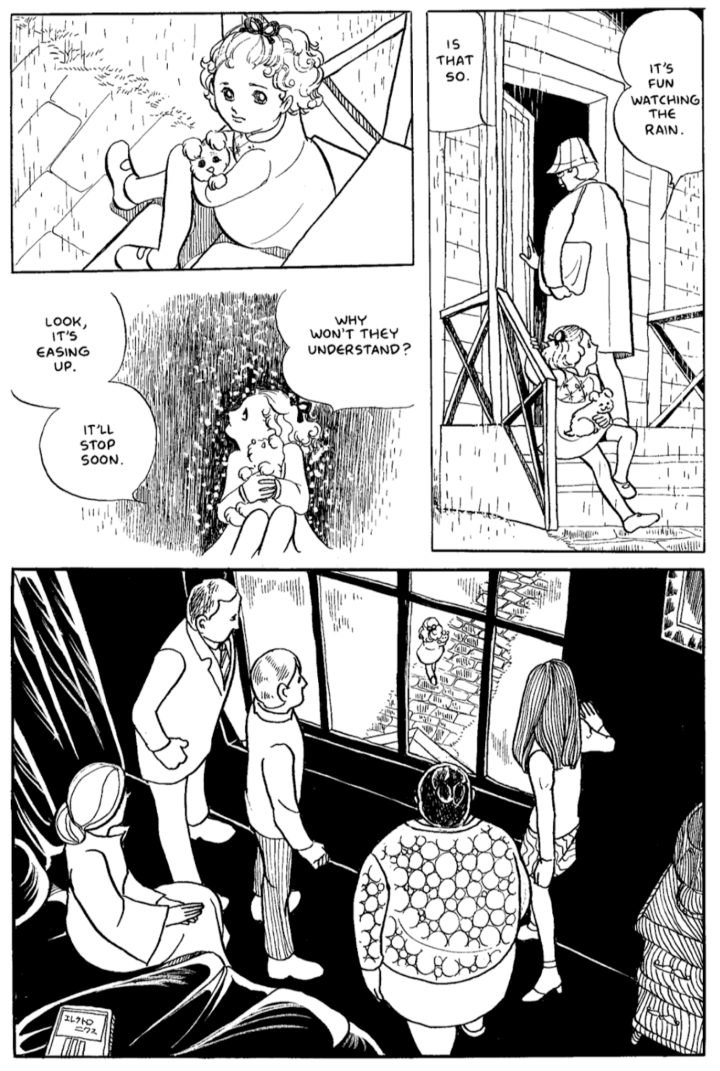

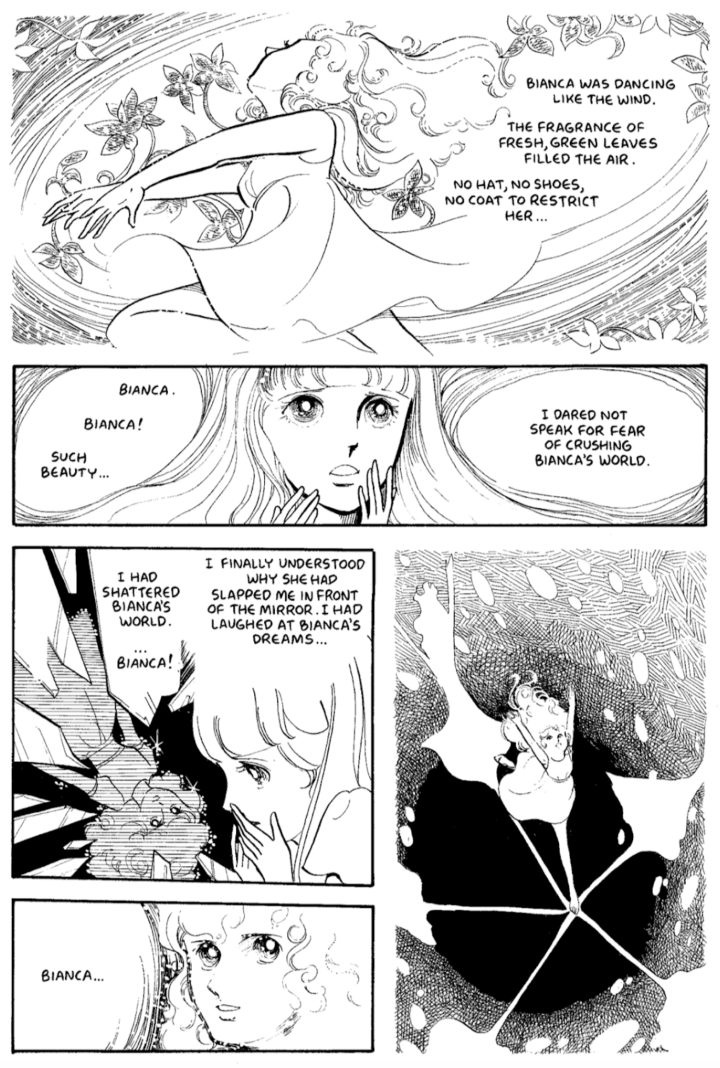

Her certainty is no less demolishing for the presence of that boundary, because sexuality isn’t the only kind of intimacy or the only field of danger on which the heart, body and mind play. Looking at the range of stories in A Drunken Dream, where target audiences seem to range from little girls to teenagers to adult women, sexuality is overwhelmingly outshone by self. The story mentioned above is more about self-worth than about romance; the story about a woman who’s spent her life seeing an iguana in the mirror is more about self-worth than it is about gender or beauty at the social levels; even the final story, so admired by Trina Robbins in her foreword, is more about self-worth than about death. You’ll notice that all of these things do relate to self-worth—that’s the unifying concept, and it’s the major focus, chosen forcefully by its openers. These are two stories that knocked me out for three full days: Bianca and Girl on Porch with Puppy broke my heart fit for mending because I’d forgotten I’d ever felt “that way.” Each is about a girl who is destroyed, literally, by being misunderstood and chastised or ridiculed for her ways of being. Only moral certainty could have brought it back: that inextractable feeling of self-worth evaporating in childhood—ego and id both dying in those woods—because… people think that you act the wrong ways. Only moral certainty—commitment to the truth of an experience—could ensure that this would be rendered in girlhood tones. That aesthetic value is the thing that broke my seal: desolation in a sweet little girl, naturally open-faced and chatty: a story or two about lost delight and the humiliation inherent to rejection of innocently proffered wonder—the lasering away of a youth of joyful, impactable strange girlishness, not through encroachment of sexuality but through the robbery and prohibition of our seriousness.

There’s an interesting old back-and-forth archived on Hooded Utilitarian, wherein Noah Berlatsky argues that it’s wrong to prioritise consideration of Hagio as a cartoonist for girls, and that it’s sexist to say that perhaps a man will fail as a critic in the face of girls’ comics. This discussion with Erica Friedman springs out of his distaste for Bianca—an ugly comic, he says. Now, there’s endless possibility in the argument over whether or not something must be equally comprehensible outside of its own demographic in order to be good or even functionally true. But I don’t think Berlatsky was right, when he describes fetishisation and morbidity. I think he’s overcomplexifying in the face of a simple story; I think that Hagio is right to “shak[e] a finger at mean repressors who are silencing inner kiddies” and, from my relation to Girl on Porch with Puppy I think that Bianca—frankly this is backed up neatly by the interview by Rachel Thorn in the backmatter of this collection—is a story in which Moto Hagio says to herself, It was wrong of them to put you down that way. It was wrong when that was beaten out of you. It was wrong for you to be made so sad. But I still remember that your sadness came from mistranslation of your joy. And I remember that that mistranslation was wrong. I think that Bianca is the opposite of fetishisation: a claim on fetishised elements in the name of free expression. It’s an attempt at retroactive self-protection: it’s moral certainty.

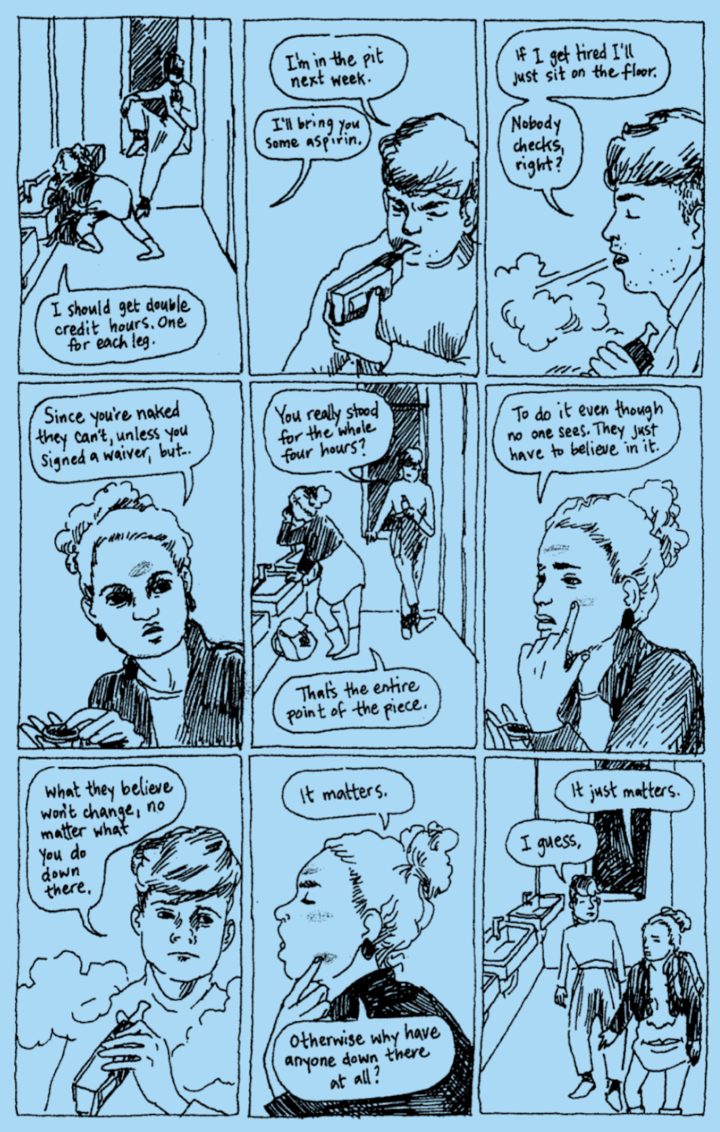

I don't think that Moto Hagio should be primarily considered as a woman when she's considered as a cartoonist, or that Julia Gfrörer should be either, but I do think that people create out of their own firmament, and that aesthetic is a delivery system for experience. I think that motif should be appreciated as the result of process, not only in the active sense but also in the absolute—the making of the artist. As Gfrörer says to Matthew Perpetua in her Comics Journal interview, “And I think that the illustration is part of the writing. They're not separate to me.”—perspective is a part of creation, not separate. Hagio and Gfrörer have shared and separate experiences that show up prismatically in their works, that are relatable across demographics, and they have those that may be missed if one does not have the context. In the interview Gfrörer discusses this directly: “My advisors and my professors would come around and be like, “Okay, what is this?” And then I would have to give them like a 10-minute-long explanation and they couldn't understand why I would be doing that. And I'd be like, you know when John William Waterhouse does a painting of a lady and he tells you it's it's Circe, then you have to know who that is? Like, is it crazy for me to think that people are going to know? Is it crazy for me to expect that people would know these things that I'm writing for?”

Waterhouse and Circe mean nothing more than what you see on a canvas if you don’t know who they are—wanting a dick inside you, being scaldingly wounded when people think you’re silly, Frasier, Japanese riverside landscaping… none of these bear more essential conversational clarity than the other. Gfrörer takes almost proud pains to offer only Waterhouse, only draw Circe, and Hagio evidently fails to get across her context to some reader cases. But Waterhouse and Circe do hold meaning. It has been accrued. It is referenceable. It is out there. It can be accessed, and by many people already has. So Waterhouse and Circe can be topics of conversation or art, and be valued, and hold function—absolutely. Even when everyone forgets, and a picture is just a picture, it’ll still be fact: this once hung within a fretwork of meaning. There is something here for people sensitive to it that I just cannot reach.

Berlatsky’s first piece on Bianca is itself a dissenting response to another critic’s analysis: Ken Parille on The Comics Journal. Berlatsky centres queerness as a lens for the story; he sees one little girl fixated on another and reads a literal text that can only be related to sapphic obsession. He notes that Hagio does not identify as a lesbian, but says that in her best work she “explores the queer knot at the heart of identity and love,” critically regretting the nonqueerness of a dead Bianca, the absence of lesbian agency, in what he considers a queer fable. Now, I know no more about Hagio’s public identity than Berlatsky; all I know is what’s written in her interview with Matt Thorn included in this volume. In there we learn that she has lived for many years with her female manager—which is something one person may do as a single person and another may do as a partner and another in another form again—but what it tells us is this: Hagio lives outside of convention. To live, as an adult, with another woman, even platonically, even married, even within your own family, is unconventional. Queerness is a world of possibility, true, a lens through which things can be experienced prismatically. But “queer” began as a euphemism in a strictly normalised system, like “gay” (frivolous) and like “straight” (honest): queer is a synonym for strange, which means unconventional, and one does not have to be queer in order to be strange. Hagio’s stories are concerned with the unconventional as much as they are concerned with self-worth, because being made a stranger is the very thing that damages self-worth, and self-certainty—moral certainty, connection to one’s right to be what one is without consideration for convention—is the only route back from hell.

If it looks long, if it looks hard, if it looks impossible… Yes, yes! You can see it.

Gfrörer, self-described, is a voluntary victim who ruins herself throughout eternity, the better to insult God. Perhaps she turns away from the road! Perhaps she is less concerned with self-worth than Hagio—it is not as melodramatically centred in her work. But I choose this adjective with purpose; it is not centred though melodrama, and the result is it’s being less obvious. But I think that it is there. Can you have moral certainty without recognising innate value in the thing that holds it so?

The post The silent rebellion of certainty: Moto Hagio & Julia Gfrörer appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment