In all likelihood, I don’t have a favorite comic. There are so many different things about comics that appeal for their own reasons, and the best should not be compared to each other. But recently I’ve thought that if I were to offer a definitive answer to a silly and subjective question, saying that my favorite comic book is Paul Pope’s THB would not be a lie so much as just a good way of not being asked any further questions. THB’s status as the ultimate argument-ender was assured for a long time by being unfinished and uncollected, with issues hard to find at what most would consider a reasonable price. With 23rd Street’s publication of Total THB Volume 1, more people can read it, and so become acquainted with the other part of my argument, which is that it’s pretty clear THB absolutely rules.

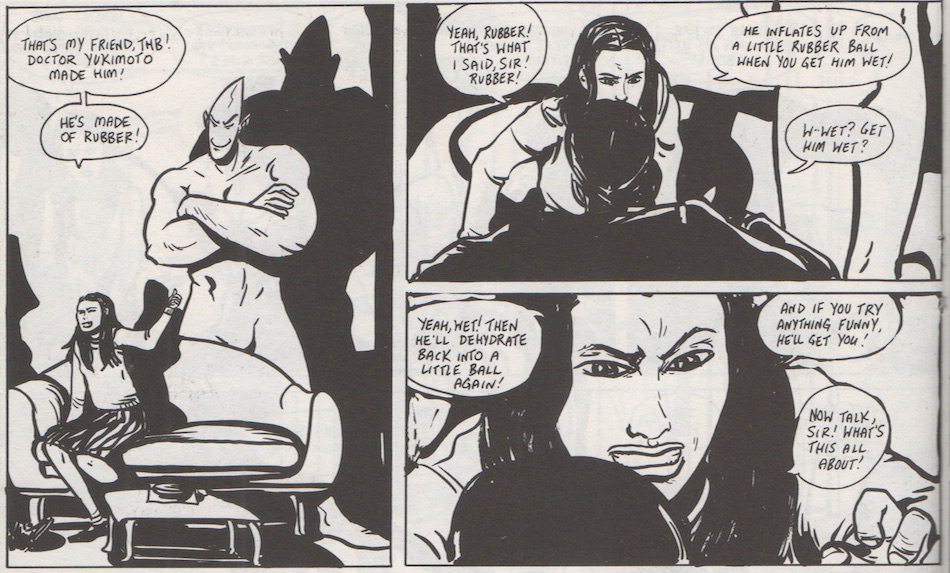

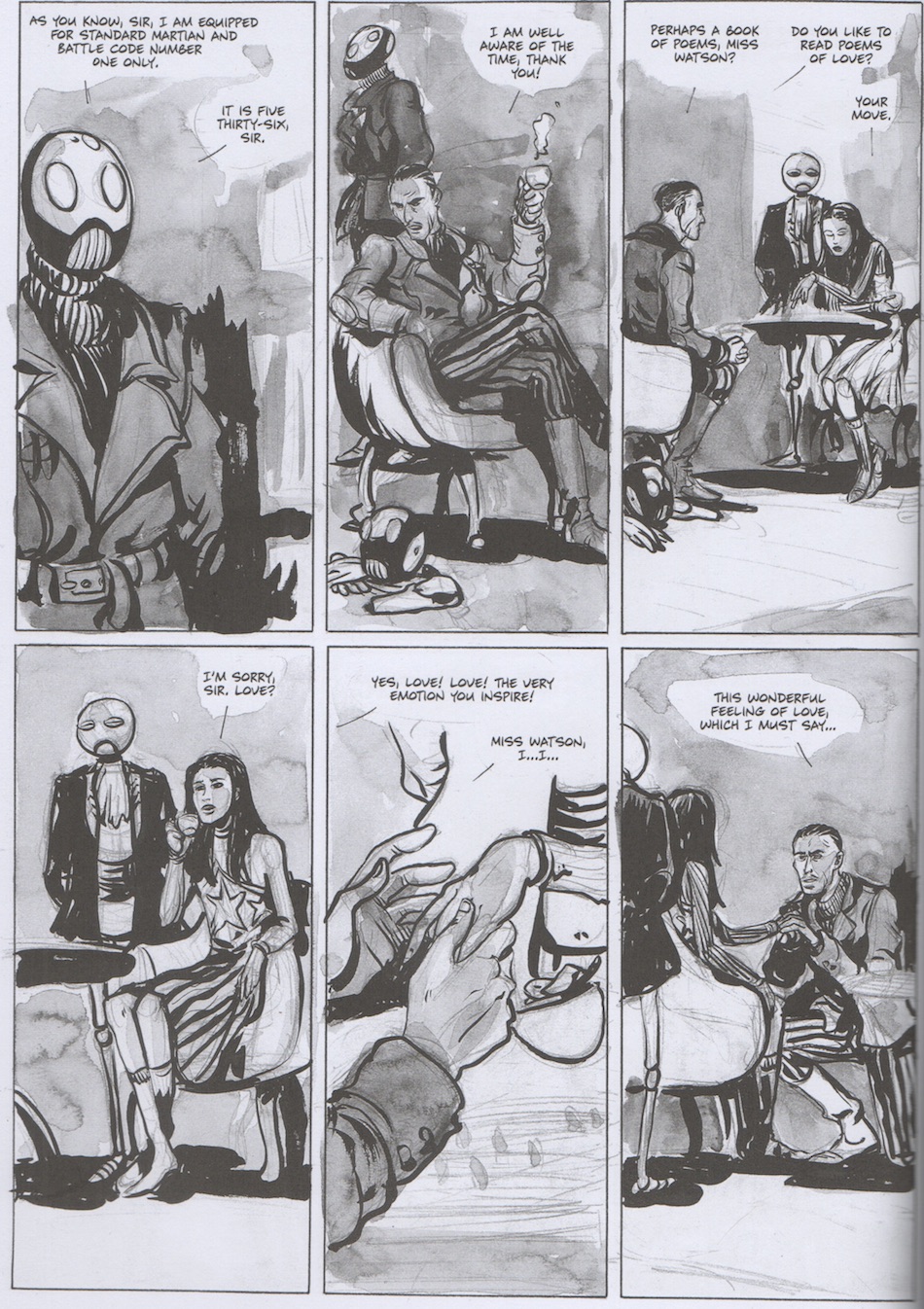

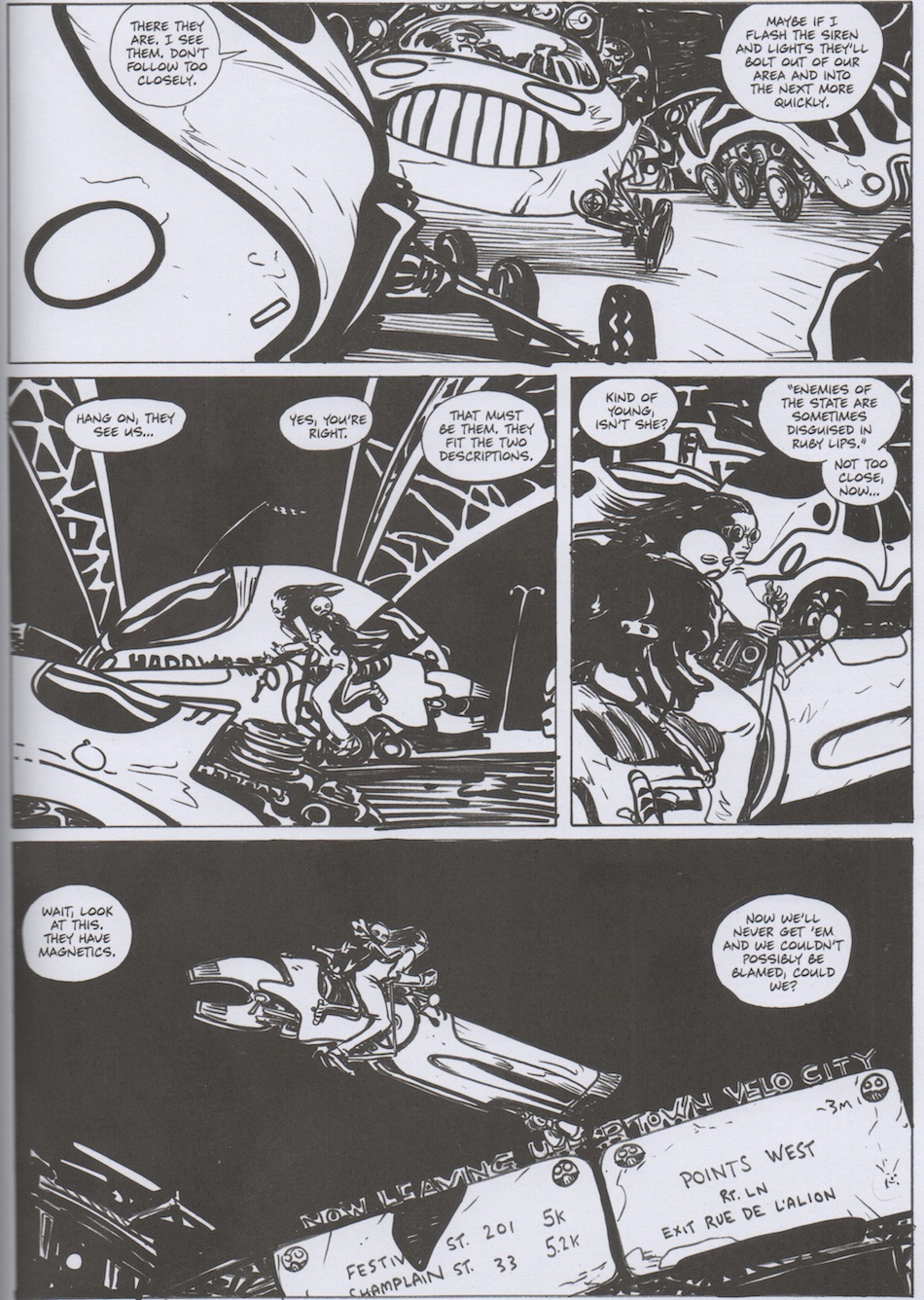

This is not necessarily because of the plot or the characters, but I should explain those things anyway. The story takes place in the far future, where HR Watson is an upper-class 13-year-old girl, living on Mars. Her father runs a robot manufacturer, her mother is out of the picture. The Watsons have a robotic servant named Augustus living with them, preparing their meals. In issue one, HR is presented with THB, a more advanced mek, who can spring to life when doused with water but otherwise stays hidden and portable in the form of a small ball. When out and about, he’s large and strong, with a consistency like rubber, and able to leap large distances. The idea is that he can protect HR from any harm that may befall her, but much of the comic is about sequences where THB in ball form becomes lost, and water is not around, and HR has to fend for herself. She is imperiled because of her father's work putting him at odds with the totalitarian government. Luckily, HR is a member of a school where fighting techniques are taught, and she is quite capable, as is her best friend Lollie. Lollie has a crush on HR’s live-in older brother figure Percy, (the adopted son of HR’s tutor, a scientist who works in robotics manufacture) who goes into the city and is friends with musicians the girls admire.

As a comic, THB distinguished itself among a field it can safely be said are not made anymore, but were fairly common in the 1990s: Black and white self-published series with genre appeal, coming out regularly enough to earn their creators an engaged fanbase and a living. Jeff Smith’s Bone, when colored for reprinting by Scholastic, would go on to be an even greater hit, but at the time it was just the most successful of a slew of self-published comics, like Paul Grist’s Kane, David Lapham’s Stray Bullets, and Rob Schrab’s Scud The Disposable Assassin, whose mainstream appeal was not diminished by their black and white presentation, but enhanced by the distinguishing elements of each artist’s drawing that color can flatten. Beyond individual drawing style, THB set itself apart by the way each issue was considerably thicker than the 32-page standard, with issue one clocking in at over 100 pages, and two through five around 56 pages each, all of these coming out, as far as I can tell, basically on a monthly schedule.

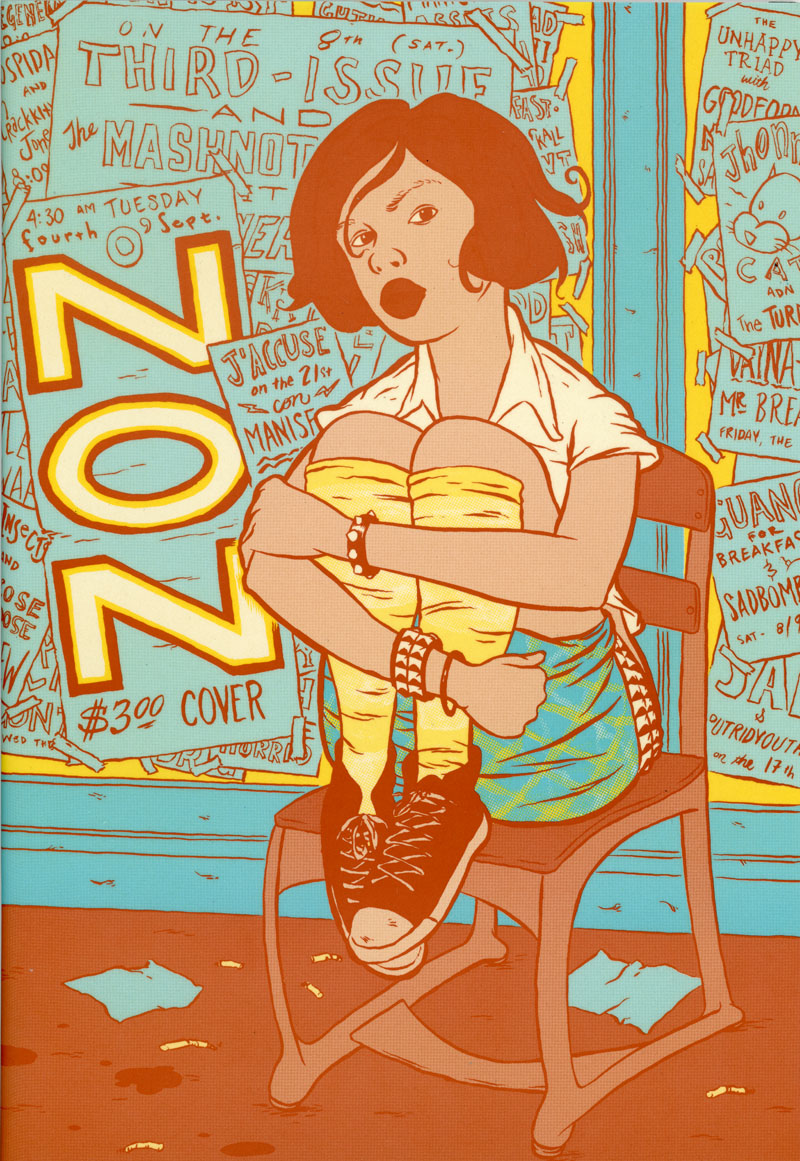

After this came a series of one-off specials, oversized to varying degrees, in a comics landscape far more beholden to the traditional comic book format than our own era is. Such design choices announced Pope’s intentions to be something other than your average cartoonist, but larger print size also underline the thing about Pope’s work that should be immediately apparent: His drawing is incredible, on a level of line quality first and foremost, with a calligraphic inkbrush technique that made an impact on anyone paying attention. People who clearly knew how to draw saw Pope’s approach and adopted bits of it as a way of drawing better: You can see Jordan Crane, in issue 3 of Non, letting his lines become looser, more organic-feeling and expressive, even if he would quickly withdraw from this approach on a way to refining his personal style. Pages of an anthology of work by SVA students show a young Connor Willumsen working through Paul Pope’s influence. The Batman newspaper by CF and Ben Jones, that’s one of the first Picturebox publications, has CF writing as a little joke “by Paul Pope” at the bottom of one page. Asked about it later, he admitted he liked Paul Pope, which is sensible. Any comics artist whose work startles in its uniqueness is going to be enchanted by the work of someone working so hard to make work that stands apart from the paradigm by making a series of distinct choices to make a comics object. What CF and Paul Pope share is that, rather than stake a claim to a place in a historical narrative by demonstrating they are doing things the proper way, they insist that the way to make an exciting comic will never be settled.

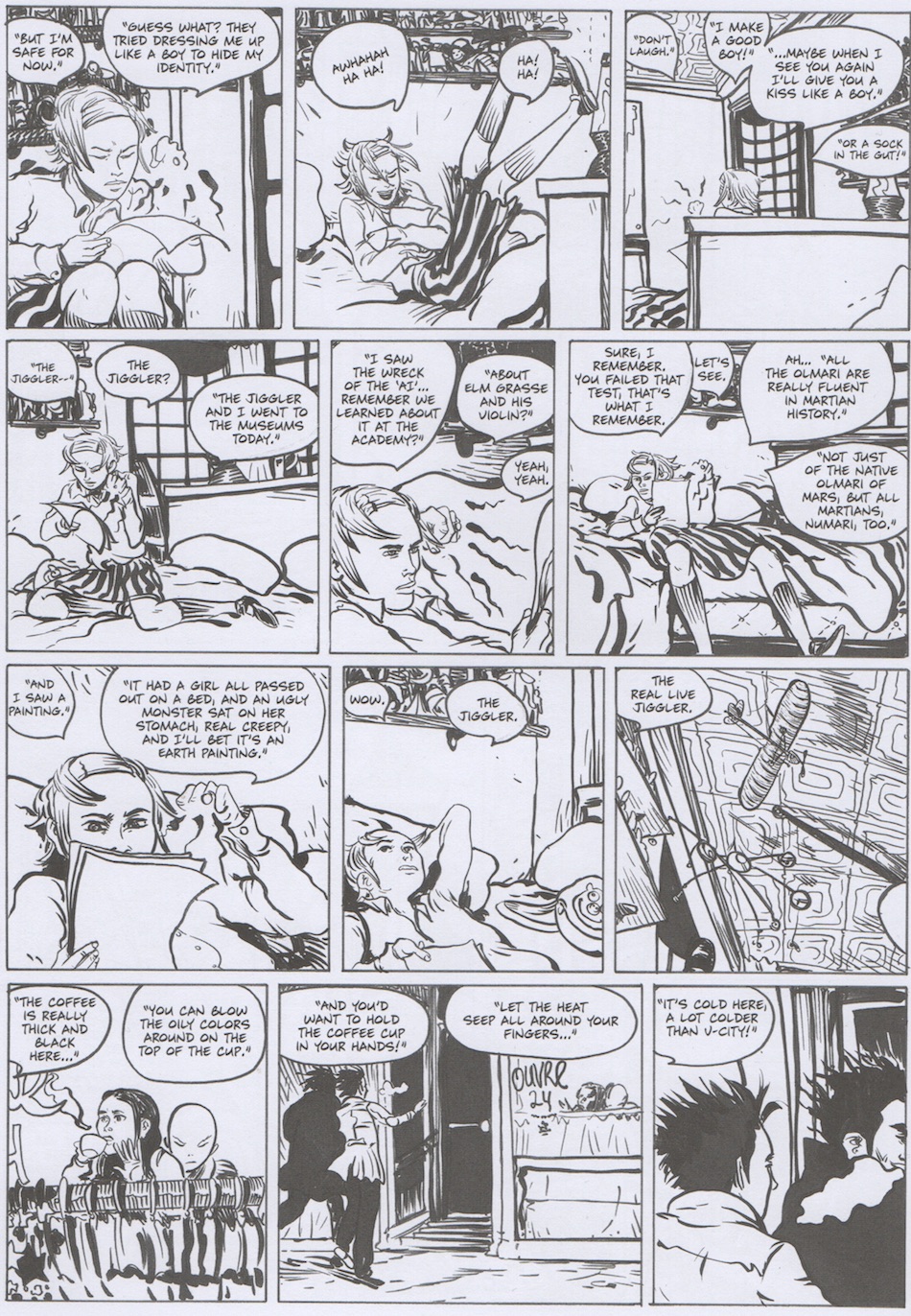

Pope made that argument through his own willingness to rework an approach to storytelling he had placed on a pedestal. As seen in the early issues of THB, at the outset of his career, Pope was a student of Italian comics, practicing an approach based around the tiers of the European album format. After issue five, Pope released a reprint of issue one which sported not just a new cover but several redrawn sections. Many of those new pages had an additional vertical inch of live area, changing the proportion of the pages to feel not quite so European. His lettering was larger, and everything breathed a bit easier and was that much more readable. It would be five years before THB 6 would arrive (as a 4-part series numbered 6a-6d), as Pope moved away from self-publishing to pursue the job offers coming in, enumerated in that reprint: Dark Horse Presents was going to run a 12-part serial, and Kodansha had asked him to create manga for the Japanese market. Those new pages, just little a bit taller than the older ones were, had him meeting manga halfway.

While some manga was available through the American market already — some of it published by Dark Horse — the tankõbon format for collections, the large magazines filled with different stories presenting initial serialization, the work appealing to wide variety of audiences rather than just adolescent males, and the way stories were paced were all such a revelation to Pope that he would need to explain the impact of learning about it in an essay wherein he presented "manga" as being fundamentally different from "comics." This is a perspective which a 21st-century Comics Journal reader might or might not agree with, but what is fascinating to me is that to discover manga in one’s mid-twenties after having doggedly pursued a study of the works of Hugo Pratt and Milton Caniff could only result from the particular historical circumstances of 1990s America. It is exceedingly unlikely any cartoonist active in the 21st century would be able to stumble onto the same path by accident. One is more likely to read a large amount of manga at an early age and spend hours of toil reproducing manga’s mannerisms and most popular shorthand. Pope’s takeaway was the way the pages move. By introducing a sense of emotional expressivism to a particularly rigorous foundation of underlying drawing, Paul Pope made work that was startlingly unlike what American comics had seen before.

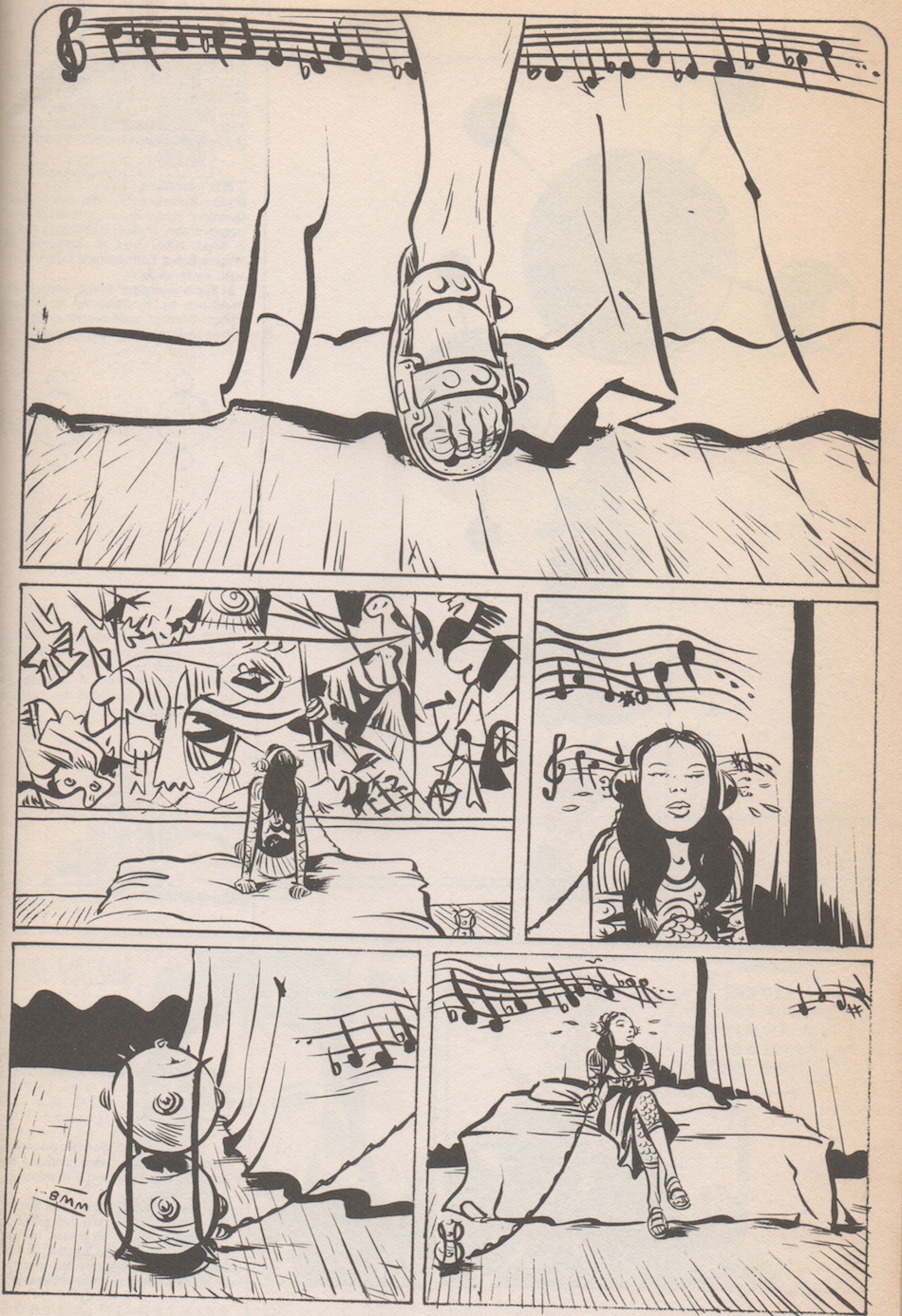

While the work in THB 6 displays a great leap forward, the early issues presented in volume one of Total THB are by no means bad. Pope was a very strong artist from the beginning, albeit inclined to a form that didn’t give him as free a rein to show off as he would later elect. Pope’s drawings emphasize the physicality of the body, and the materiality of objects. Gesture is captured, enacted in movement. This is the baseline Pope is working from, even though THB is by no means a comic of wall-to-wall action. The figures have weight, and when people are not in motion, and they are standing around, there is a sense of weight to their presence that then becomes metaphorical, emphasizing stillness, a sense of quiet as something uncertain and loaded. This is a quality you can see in David Mazzucchelli’s work as well, particularly in a story like Rubber Blanket's "Big Man." There is something stately to the European-styled approach, which is able to achieve a melancholic depth, an emotional charge rare for a science-fiction comic.

There’s an exceptional sequence at the end of Total THB volume one, where Lollie is reading a letter that HR has written to her in code, from a place Lollie’s never been. Part of this letter describes a soda called Whopp, and how the bottle works. This is typical science-fiction world-building, but presented with a sense of concentrated emotion, as Pope describes this world he’s built through the form of a friend trying to convey a new set of experiences to someone with whom she shares a great amount of history already. When the letter ends, we cut back to HR in her new locale, with the new friend she’s made — a martian whose band she’s long admired — and they climb out of a window onto the roof of a building, and in the street below, there’s a salesman walking around selling Whopp. Pages later, the book ends on a pregnant pause, a bit of suspense, as THB suggests to HR that she probably shouldn’t have written the letter at all, due to the likelihood it would be intercepted and used to track her down. This is such a sad, melancholy idea, that safety can only be ensured if one does not attempt to communicate with one’s closest friend. It’s so quiet, and so dignified, for an ending to an installment of a genre comic.

This originally ran at the end of issue 4 of THB, which now constitutes an act break in the long-promised book edition repackaging of the series. What readers will receive from the collection is pretty close to what Pope drew in 1994. There are exceptions, which are partly marks against it. The cover design is pretty bad: For a guy whose work is clearly drawn very large then reduced in size for print, it’s an odd choice to focus on a small detail and blow it up large, even before the addition of gradient coloring and spot gloss. This is a minor complaint, as the interiors look pretty damn good. Rescanned artwork adds a great deal of depth to the textures of a sequence done with wash so it is now clear it was printed much too dark originally. Lettering is replaced with a font made from Pope’s handwriting, likely to make translation easier — I think a clearer “B” could’ve been chosen — and a bit of expressive flair is lost in the conversion, with the word balloons seeming a little larger and emptier from the standardization of letter size. Rewrites to individual lines are rare and minor, at least as far I can see — “I need to talk” replaced “I want to talk.”

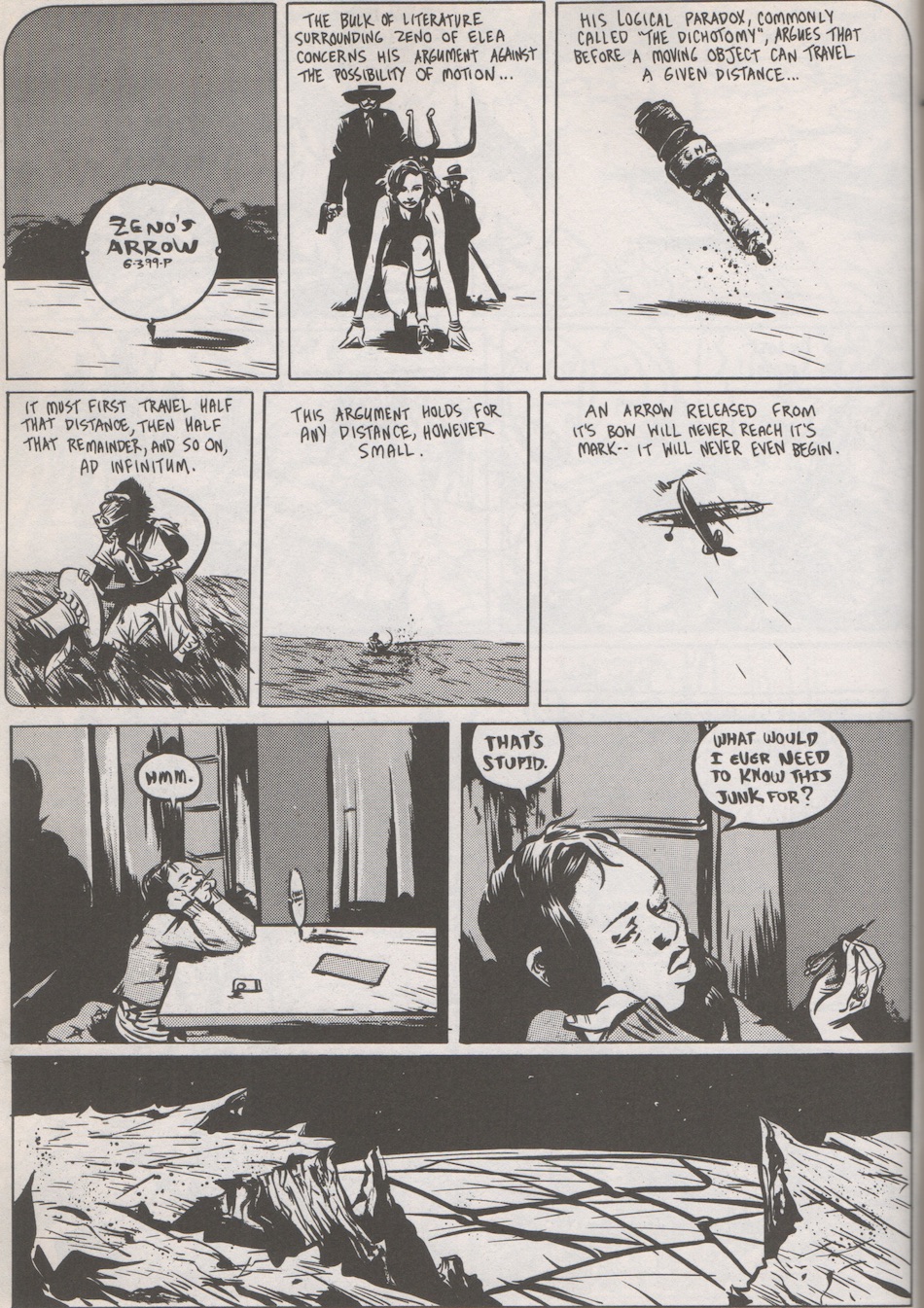

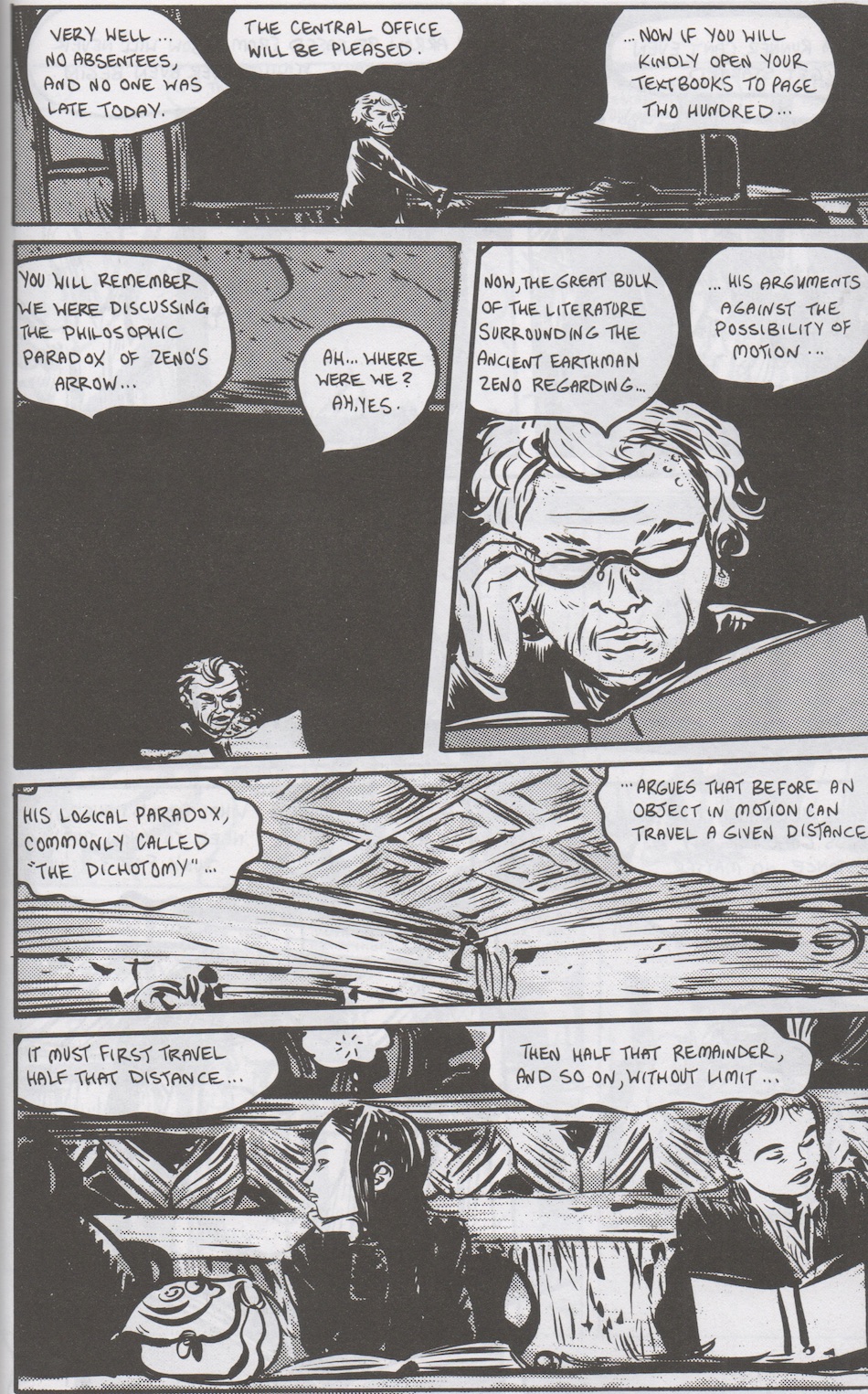

I expected a complete redrawing of the series. That reprint of issue 1 with a significant amount of redrawn sequences — what we might call version 2 of issue 1 — came out in 1995, preceding George Lucas’ 1997 rerelease of Star Wars with updated visual effects. It’s easy to call Lucas’ decision a travesty, a disservice to film history, and still find Pope’s tinkering interesting. He was not changing work decades later due to advances in technology, but as an artist whose craft had advanced over a relatively short time span by having been exposed to both a new type of storytelling and drawing hundreds of pages in a concentrated amount of time, revising his work for a second draft. In subsequent issues, other sequences that had previously seen print would be redrawn. The first page of comics in version 1 of THB 1 is an educational strip elucidating the concept of Zeno’s Arrow, and was redrawn as a back-up in THB 6a. A back-up story in issue 2 of THB, showing HR and Lollie getting milkshakes at a mob-run establishment, was redone completely for a story in THB: Comics From Mars 1, published by Adhouse Books. The changes in the redrawn version illustrate how Pope’s sense of comics storytelling changed over the years. Page one now falls on page four, following three pages of wordless storytelling, including a two-page spread, easing you into the world of the story by giving the reader a moment to acclimate and appreciate the visuals first. It’s gorgeous stuff, and feels far closer to manga than European comics.

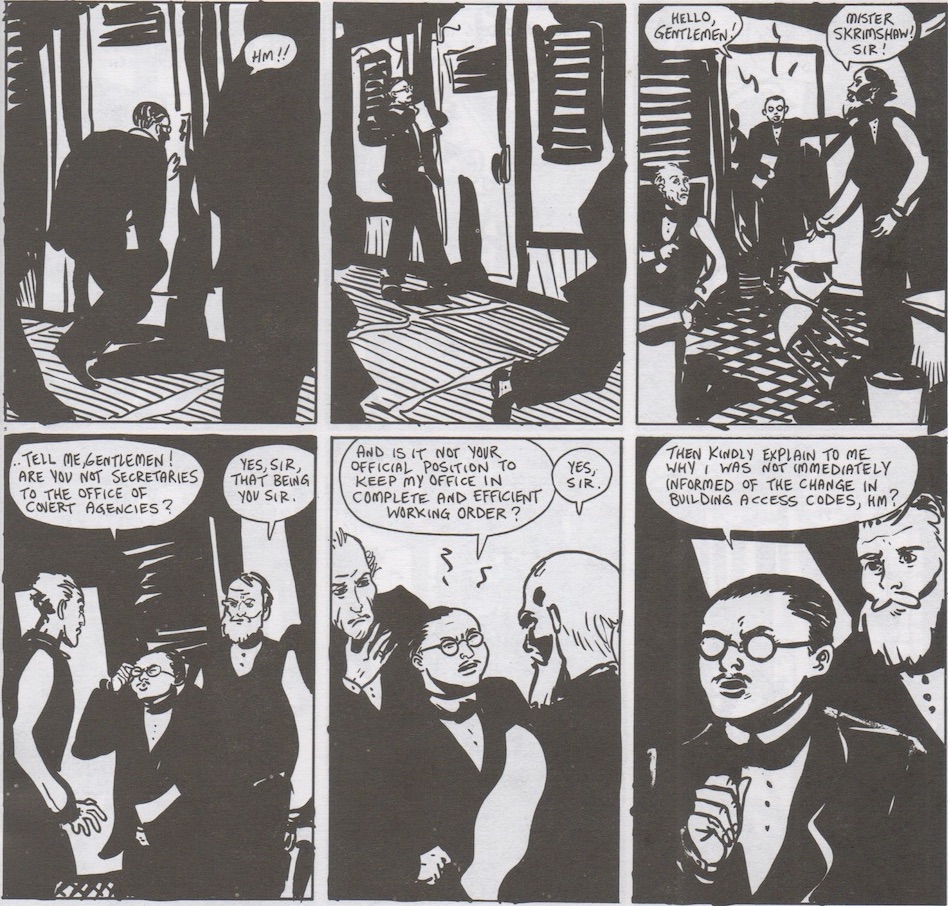

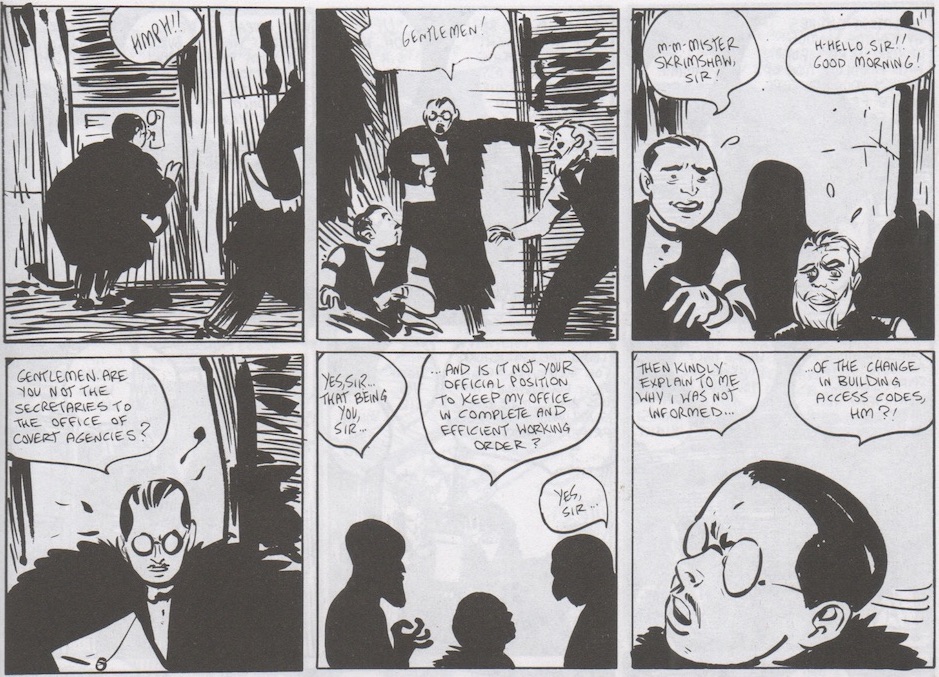

Total THB favors the initial printing of THB 1 over Version 2, and none of the new parts are included. However, in that first version of THB issue one, there is an extended silent sequence of HR chasing a bat she’s accidentally released from a jar. It is a scene which, in context, is perfectly charming as a showcase of visual storytelling, but version 2 deletes it because it doesn’t really do anything storywise, and it’s absent from Total THB as well. Another sequence, focused on a bureaucrat working as a censor, who secretly loves the material he suppresses, as do the people above him, was completely redrawn for its appearance in Version 2 and is likewise deleted. It strikes me as a shame that this sequence was removed: It expanded the sense of the book’s scope, although this is also the argument against its inclusion, from an editorial perspective: Deletion of this scene keeps the focus on HR Watson.

Total THB is released by 23rd Street Books, a parallel line to First Second meant to focus on comics for adults now that First Second is associated with material for a younger audience. A few years ago I wrote a piece about the world of middle-grade comics being put out by book publishers. Speaking to Mike Dawson for that article, he mentioned that editors suggested kids would not be interested in a subplot about the child protagonist’s parents. and I can’t help but see the loss of Pope’s scene in that light, keeping the focus on the protagonist to make the book more relatable. However, to be novelistic, you need space to digress. Total THB, in the early going, moves a little fast and a little abrupt, and I think it’s in part because of these edits.

By removing this sequence, the book stays focused on its main narrative thread, and by not including the revised sequences, we see Pope as the artist he was in 1994, with no breaks in the consistency of his drawing to suggest the fact that he’d become a stronger artist immediately after. As I think one of the best things about Pope is his willingness to rethink approaches to comics, one of the things I find most compelling about THB is these revisions, which show development in his approach. Similarly, I think some of the best parts of THB exist outside that main narrative thread. The pieces in P-City Parade, THB Circus, Giant THB Parade — those to me are Pope’s peak, and the peak of THB as a whole. Partly it’s the joy of seeing his work oversized, and I wouldn’t expect to see that aspect recreated for the bookstore trade. But I also appreciate the exact thing a book editor would not, which is the way these bits play against the expectations of a linear narrative, eschewing the form of the novel in favor of the historical truth of comics: A newspaper strip like E.C. Segar’s Popeye could tell a serialized story from Monday to Saturday, while leaving Sundays free to operate in a different register outside the bounds of the plot’s progression.

While issues 1 through 6 and 2003’s Giant THB tell a story with a sense of forward progression, presenting our main characters subject to escalating tangible dangers, these special issues don’t. They present HR and THB, running through the streets to deliver a cake, or running afoul of gangsters at the circus. The timetable to the series proper is pretty tight, with Total THB Volume One taking place over a few days, and leaves no room for sidequests. A reader might extrapolate from the series’ tone of genre adventure that HR will make it through the story OK, and these stories from the specials, more lighthearted and deliberately frivolous, would happen after the story arc’s conclusion. However, assuring the comic book audience that, despite all sequences of suspense and cliffhanger conclusions, everything will be fine and our heroes will be laughing about all this in no time, is a move certain segments of the readership do not appreciate. I think it’s fucking great that Pope provides this apocryphal or filler material, that build out his sci-fi world while doubling down on the fact that these comics have as their ideal audience teenage girls who will allow themselves to appreciate something fun and disposable that does not take itself too seriously.

Total THB’s elisions remove the parts of the story that step away from the central subject of the teenage girl protagonist, and so perhaps accommodate the expectations of that audience as currently envisioned, theoretically disinterested in stories that don’t directly concern their self-representation. This disrespects their intelligence, suggesting they cannot handle the difficulty of a novel for adults which would include digressions, but it is also a move away from what the magazine format offers a reader, an abundance of content they can take or leave at their leisure, or skim over depending on how they feel. THB in its comic book form comes closer to that ideal of the magazine, a format I believe women and girls love. Those are who the successful magazines, the ones you saw at every drug store and grocery store checkout, were for, back in the waning days of print supremacy.

This is not to suggest I think the extraneous material, the essays and letter columns included in issues of THB, should be preserved in a book. But I do think that stuff — which included a few photos of girls, Hope-Sandoval-style waifs the lot of them, included music-magazine-style, cast for their resemblance to the characters of THB — was a part of what the issues were doing, building out the world and its emotional resonances with its readership. Part of the book’s sense of romance is about listening to music: the moods it suggests as it takes you away, the aspirational future it presents to young people. Pope includes pop culture in the world-building aspect of science-fiction. Part of the challenge he sets for himself in depicting the emotional life of an adolescent has him conveying the way music feels. It’s this investment in depicting feeling that led him to both manga’s formal language and the design choices of music magazines. It is within the text sections of those issues where things that would never arrive were continually promised: a story called "The Wing-Tip Caper," to be inked by Jay Stephens, a graphic novel called Pig Dog Parade. This to me is part of THB as well — these concepts to dream with, to conjure with — though there is no room for this sort of effect in Total THB.

The romance is still present throughout, imbuing the action with this sense of extravagance. One sequence has HR and Augustus making an escape on a magnetic vehicle you can basically understand as akin to a motorcycle, with Pope’s brushwork giving way to huge swaths of night sky black. As they make their way through the city, gaming out potential routes, HR laments the depressing state of the botanical gardens they’re passing by. This perspective crosscuts with the surveillance of bureaucracy pursuing them, who map the space of the city in their own set of codes, even as individual members want to avoid the paperwork that comes with actually doing anything. We see a big world, occluded by the black of the night, and isn’t that the stuff of poetry, or life itself? After plot threads converge, and HR reunites with THB in an action sequence, a narrator speaks with a voice unbeholden to any in-story character's perspective, free to be indulgent. THB at its best exists in this elevated space, this disquisition on the story it is telling and the world it occupies, never dumping exposition but allowing the characters moving through the space to have inner lives tied to its vastness.

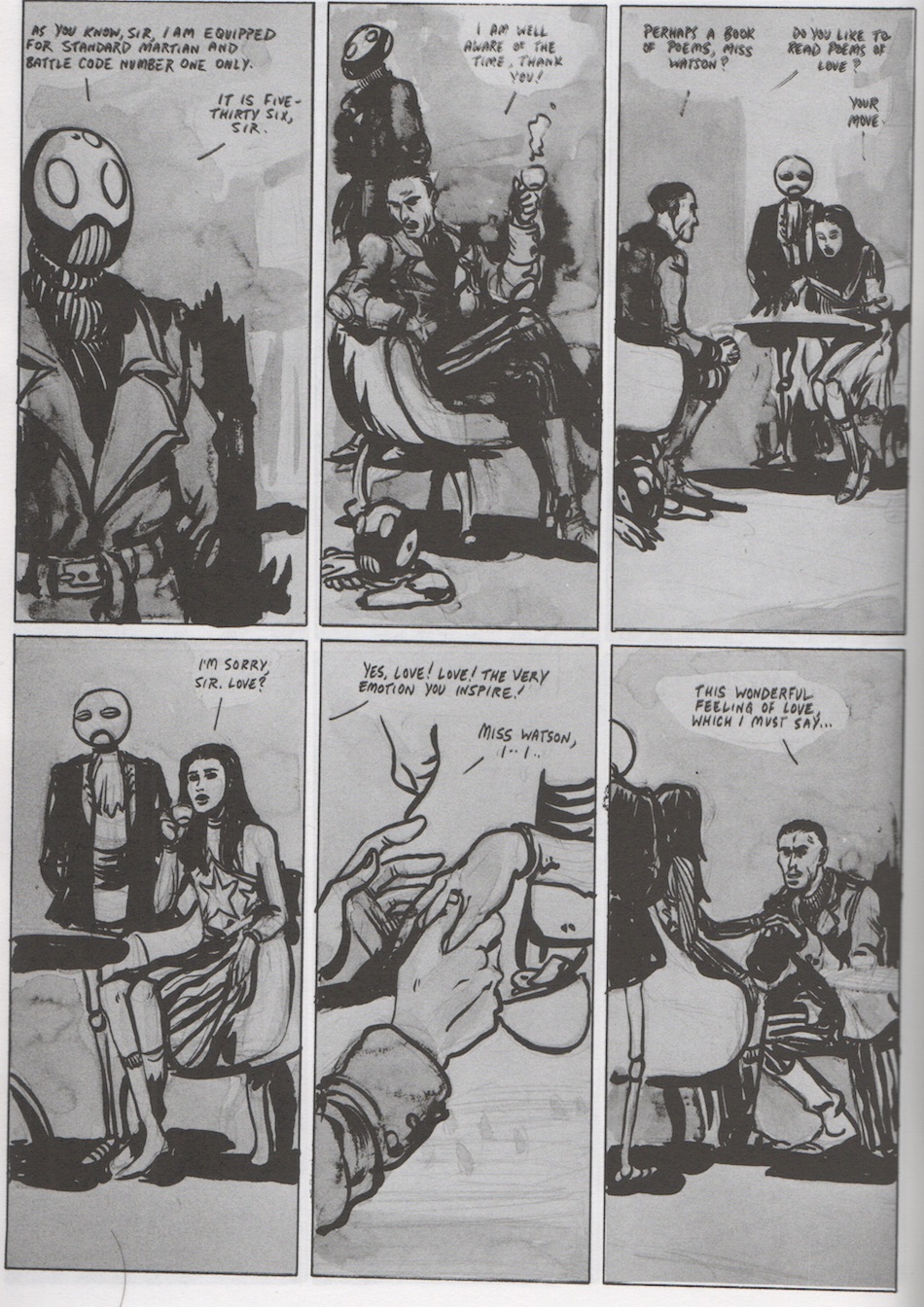

Another scene with the bureaucrats has one functionary being chewed out, being forbidden from writing poetry. He hasn’t, and insists the note they’re looking at is just a laundry list. But the bureaucrats — the government workers known as Bugfaces for the anonymous-making masks they wear — have no eye for poetry, and in being unable to recognize it, eye the list suspiciously. Meanwhile, THB professes he is a mechanical being, not technically alive, but is always smiling, and has a voice and sense of humor we come to know and understand. Pope understands the double-act by which the practical and the poetic correspond in comics like few others, making work that feels profound in the scope of the feelings evoked in the course of storytelling. It's the mixture of these little asides and huge set pieces that account for why the issues of THB needed an expanded page count.

You can also see the revised pages and side stories not included as being the bits where Pope comes closer to his conception of manga. The work Pope produced for Kodansha was called Supertrouble, described by him as being like the HR and Lollie bits of THB but without the sci-fi elements, like the presence of THB itself. Pope talks about his own tastes in manga throughout a number of text pieces in issues of THB. Happy by Naoki Urasawa is the only thing I’m aware has seen print in English. The other series — Junichi Nojo’s Gekka and Kishi, King Gonta’s House Of Hell, and Masayuki Soma’s Pao Pao Akko — I have only heard of through Pope’s praise. Years later, writing in Tom Spurgeon’s “Five For Friday” column, Pope again named King Gonta and Masayuki Soma, alongside Minetaro Mochizuki (of the series Dragon Head, coming back to print later this year), Tatsuya Egawa (of the sex comedy Golden Boy), and Suehiro Maruo. This list is interesting because it is neither the greatest hits of a shonen-reared youth nor a scholar’s idea of historically important and influential work. It is not a fashionable Japanese person’s idea of what was cool at the time. It’s an outsider’s take of what was exciting and foreign in contemporary manga, based on what was provided by a publisher, who included a look at the work of their biggest competitor. European cartoonists Igort and Baru were producing strips for Kodansha at this time, and David Mazzucchelli was also commissioned to create work, although like Pope’s manga attempts, it was never released.

The plans for Total THB currently only include three books, and from volume one’s act break, one can presume volume two would include issues 5-6c, with volume three consisting of 6d and Giant THB and hopefully previously unseen material. This approach — focused on the linear narrative of the main plot thread — would not leave space for the stories I’m citing as the high point, which is a shame. In a recent interview, Pope said he thought there would be five books, which could accommodate the material I’m naming as a highlight, although it would have to be at a greatly reduced size. As it is, the dimensions of Total THB volume one present issues 1-4 at a slightly larger size, due its squarish size and the more European-album formatted pages. I appreciate that Total THB does not present itself in a manga format, or tries to pursue the manga readership through some kind of trickery. The book dimensions feel like it’s insisting you meet the work on Pope’s terms, almost to the book’s detriment actually, as the way the typesetting presents the name Paul Pope on the cover announces him as an artist the audience has already heard of, which I don’t think is guaranteed.

My larger objections to the book edition boil down to a complaint that the editors took a weird thing and made it normal, which makes it less inspiring. At the same time, it’s been thirty years, and that is long enough for most artists’ innovations to become metabolized by the larger cultural bloodstream to some extent. Pulp Fiction came out in 1994 too, and precipitated a wave of rip-offs that, if they do not dim the impact of the original, still turn perception of the time period into an era rather than a forever-onrushing modern moment. If Pope was on the crest of a wave of Americans engaging with manga, now that the tide has turned, his impact stands as its highest watermark, which is not as impressive of a sight when you’re standing on the still-wet sand.

Still: Now you can read it, if you haven’t before. So can the proverbial kids, whether they be adolescents the age of HR Watson, or young artists working their way through the history of the medium. Parents and uncles, college professors and comic shop employees, are all in a better position to place this book in the hands of those who need to read it than I’d be able to lend out my original issues as a longbox trawler. Many would appreciate it. Young artists are often given the advice to not have the first comic they attempt be a huge epic based on lore and world-building built up in their heads over the years. They’re told start simple first, build up your storytelling chops; you are not likely to realize your ambitions on an early go, if you complete it at all. THB is both a cautionary tale of why people should not attempt such a thing — it’ll take you thirty years, as you get sucked into other things, and you’ll be hounded about completing it all the time, with people thinking you’re a liar whenever you say you’re working on it without new printed pages to show. It's also a best-case scenario of how impressive it can be if you pull it off, and what skills you need as an artist and a writer for the work to stand the test of time over the years it takes to complete, weaving all the details of his world into a very direct story that continually expands its scope, introducing more and more interesting characters.

Throughout the original issues of THB were photos of Paul Pope himself, sometimes with his shirt off, sometimes smoking a cigarette, and I don’t think anyone will be let down to learn these have been excised from the book collection, save a single author portrait. Brian Chippendale, interviewed in issue 256 of The Comics Journal, said “Paul Pope I think is really good, although if I have to see another picture of him in his studio blowing smoke, I’m going to puke.” Those photos, like the photos a reader could interpret as resembling HR, were concrete realizations of an abstract idea: You are meant to imagine your way into the transformative power of these comics. Readers can identify with the characters or they can identify with the artist. The artist, too, is a romantic figure, but as HR romanticizes The Jiggler, as the sound he makes summons images and feelings, only to later be able to meet him in person, so too can the world of THB be met, after years of imagining it as an abstraction, now that Total THB is available.

The post Canonizing Pope: The Case For <i>THB</i> appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment