For the fifth time I return from England’s Thought Bubble Festival, with a suitcase full of books and another smaller suitcase half-full of more books, and so it is time to tell you about some of these books so that, of the upwards-of-a-thousand dollars I spent, Fantagraphics’ accounting department will give me one hundred dollars back. We call this “breaking even,” here in the comics biz, where no one knows how to do math.

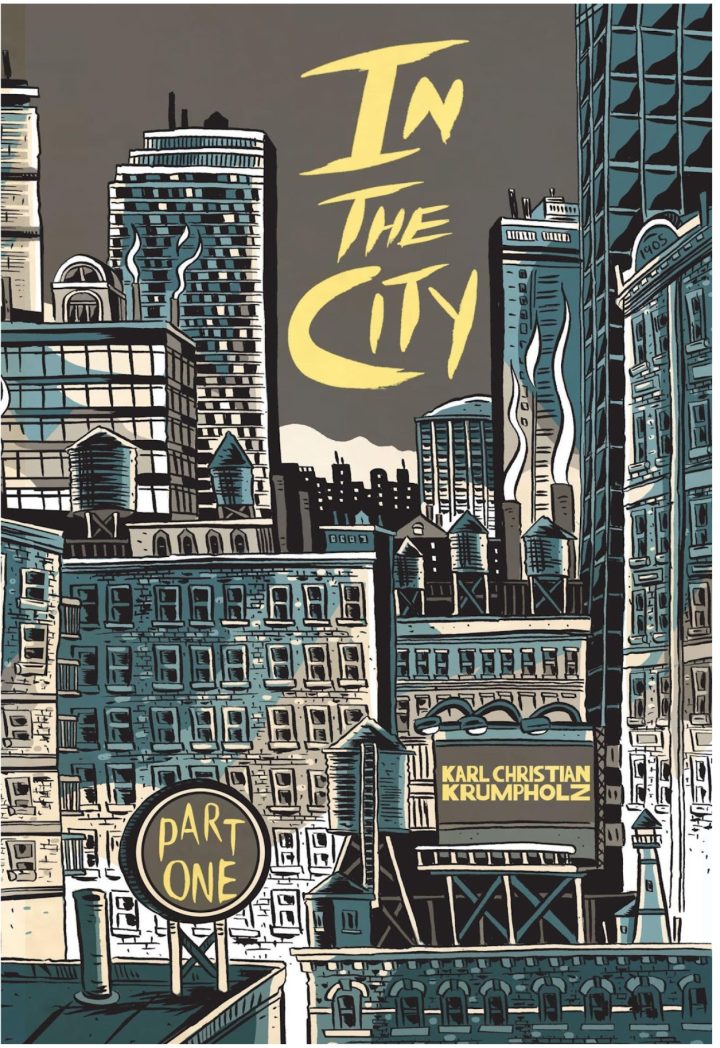

Colorado cartoonist Karl Christian Krumpholz has been tabling at Thought Bubble for four years straight now, though this was the first time I actually managed to buy books from him. Krumpholz has been serializing his graphic-novel-in-vignettes In the City, digitally and in print, since 2022, and so I got to sit down with the first four parts — each a perfect-bound unit of 48 pages.

In the City is a work of autofiction, centered around Krumpholz and his wife Kelly; in lieu of “Denver” proper, where they live in real life, Krumpholz’s marketing copy simply refers to the location as “The City,” indicating a desire to play fast and loose with factual specifics in the hopes of achieving universality (a desire underscored by the epigraphs on the theme of urban life prefacing every chapter, three in every issue, ranging from Baudelaire to Yung Lean).

The limited palette of Krumpholz’s cartooning, defined by ranges of blue-green and yellow-brown, evokes Seth’s yesteryear-landscapes; his linework is spontaneous, with nary a ruler in sight, combining the sharp strokes of Jeff Lemire and the occasional curvature of Peter Bagge (limbs like rubber, the ground arching underfoot). It’s a charming sort of patchwork look, sedate but not texturally lifeless.

What becomes evident right away is Krumpholz’s reluctance to dwell on the day-to-day — outside of a handful of throwaway panels depicting him at his drawing desk, there is little indication that a day-to-day life exists in any constraining fashion. Instead, In the City focuses on the leisure component, as Karl and Kelly alternate between cafés, museums, bars, and concerts, with intervening encounters on the street as well. It’s an interesting approach, placing the couple, as characters, in a position of relative weakness: their default state being a state of flux, they become less their own people than vehicles for external experience.

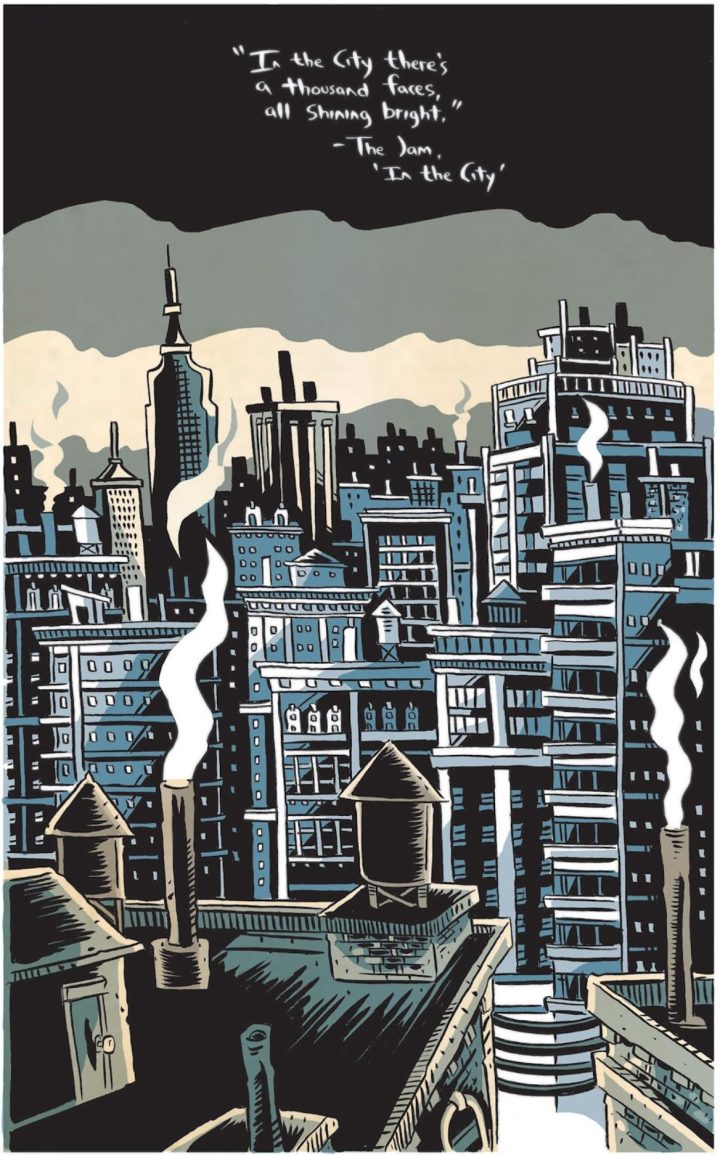

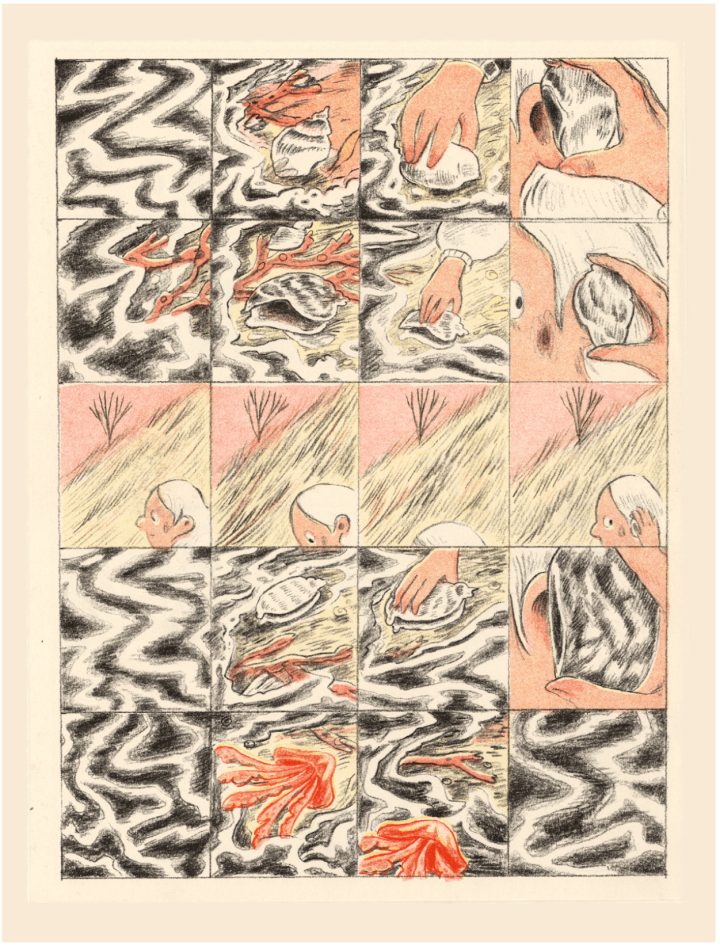

This choice, in turn, reveals a certain struggle in the cartoonist as well, as Krumpholz fails to properly articulate his moments — there are episodes that might have approached a Pekar-like level of observance, but in prioritizing an air of predominantly-social verve and bustle Krumpholz reveals the impatience of his own narrative hand. For a visual manifestation of this impatience, we may look to a specific sort of page layout that recurs several times in In the City (this specific page being from Part Four):

This sort of structure—sluicing, at once linear and simultaneous—betrays, to me, a sort of avoidance: the inset panels with their dialogue offer a glimpse at specificity, but only a glimpse, fleeting and lacking in anchor. Such glimpses abound in Krumpholz’s city, snatches of lives lived otherwise exclusively off-panel, simply because the ruling force here is brevity. Another instance of these pages, even more frustrating, appears in Part One. As Karl and Kelly go to the Denver Art Museum, a double-page spread from a bird’s-eye view shows the couple maneuvers the crowds, Gianni De Luca-style, while inset panels give similar hints of the local color: two people taking a selfie in front of a painting; an old lady asks uneducated questions of a patient staff member. The art on display at the museum receives not a panel’s worth of focus. To reduce this experience to the ‘static’ of its coincident hoi polloi feels not only like a missed opportunity (reinforcing the constant socialization rather than slowing down for a brief contemplation of beauty), but also like a contradiction of the overt enjoyment and engagement evident in the couple’s own facial reactions and body language.

This attempted observationalism, though novel at first, over time gives way to voyeurism — not necessarily in the strictly ‘illicit’ sense (seeing as the characters are all either fictionalized or one-scene appearances, there is little harm done and thus little need for discoursing ethics) but nonetheless in the sense of the unaffected outsider. Krumpholz does fare somewhat better when characters recur, as both his readers and his own stand-in are given the opportunity to adjust their reactions to these characters over time: one friend, Den, starts off as a stock ‘drunk bar regular’ character, gaining depth as the consequences of his lifestyle become evident (one time he is jailed and Karl and Kelly have to bail him out, another time he coughs blood seemingly without noticing); another acquaintance tries to rob the couple on the street before recognizing them and trying to strike up chummy conversation. The tragic implications of said acquaintance's source of income being reduced to theft by assault are undercut when he later jokes about mugging them and makes an asshole of himself, prompting Karl to punch him in the face (the first time, notably, that Karl has taken action for himself). Even in these instances the very conceit of the comic, wherein Karl and Kelly are the exclusive subjects, means that other characters are disallowed from receiving their own autonomous focus, their very lives merely subordinate to Krumpholz’s.

Karl Krumpholz's storytelling reads from the belief that in order for the individual to thrive they must allow themselves to melt into their environment; I think he believes in it, too, wholeheartedly. But In the City the non-committal nature of its secondary (and tertiary) characters, betrays a certain fear — that, by melting into one’s environment, one might risk losing sight of oneself. Not an unreasonable fear, but a pernicious one all the same. As it stands, Krumpholz portrays the people in his city as in a mirror, dimly; whether or not they will see one another face to face, only time will tell.

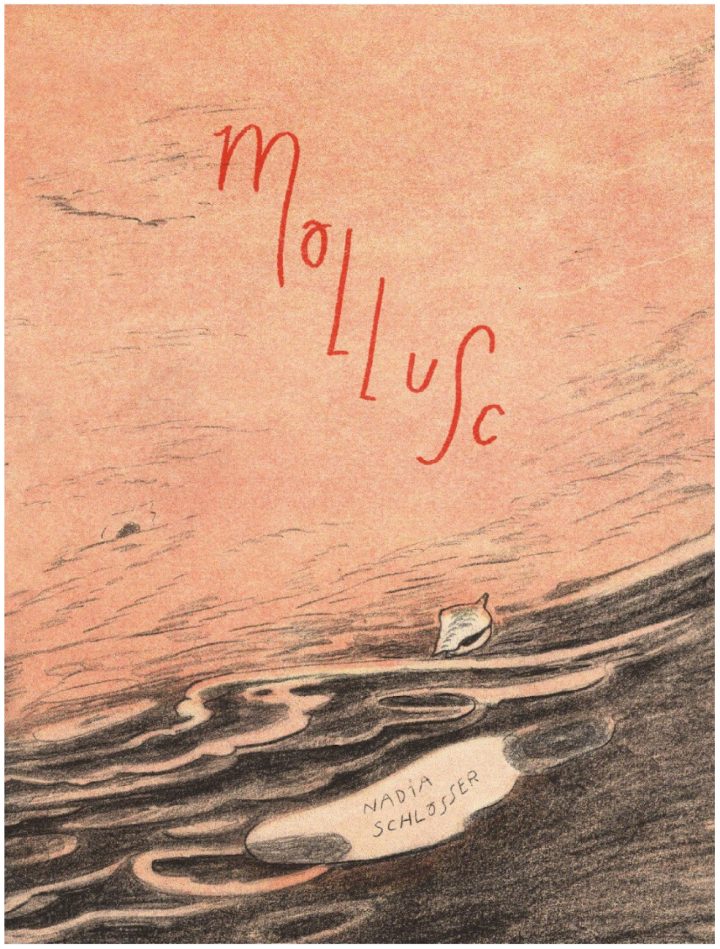

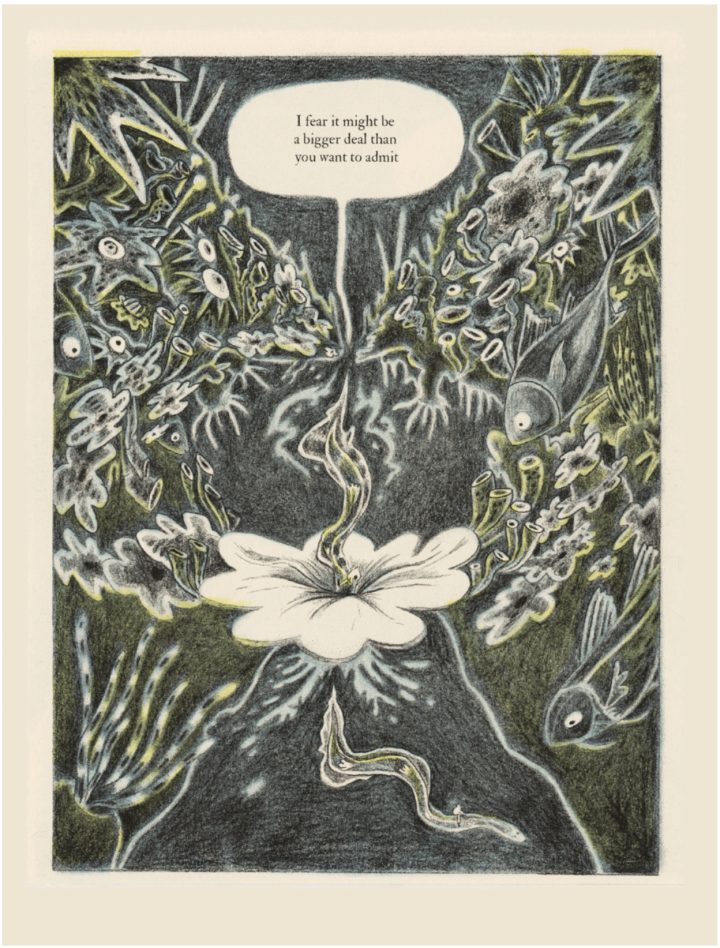

Where Krumpholz deals with the human world, Danish cartoonist Nadia Schlosser shifts her gaze to the solitude of the natural. Writes Clarice Lispector in “Dry Sketch of Horses” (1974, tr. Katrina Dodson): “But—who knows—perhaps the horse himself doesn’t sense the great symbol of free life that we sense in him. Should I then conclude that the horse exists above all to be sensed by me?” It is from this framing of nature—as less an autonomous experience than a surface for allegorical projection—that Schlosser’s self-published outing Mollusc emerges.

Mollusc starts with a walk on the beach: a nameless person—broadly femme, though the back-cover copy employs neutral pronouns—picks up seashells and presses them to their ear. After a succession of such attempts, a crab leads our protagonist to a bigger conch, and when they press it to their ear a mollusc emerges and crawls into their mouth. From this point, the protagonist merges with the mollusc and dives into the depths of the dark sea, literally and symbolically.

As time wears on it’s more and more rarely that I get to properly ‘discover’ cartoonists I’m unfamiliar with at conventions. Even spending two days on the show floor, I inevitably get drawn into long conversations with the people I know and rarely get to see, and the creative experience winds up superseded by the social experience.1 Of the myriad exhibitors I bought from, I’m pretty sure Schlosser’s is the only name I hadn’t heard before. This is, in itself, a credit to her: her art is immediately welcoming and eye-catching even from afar. Her hues are warm and pale, and although the version I have is the digitally-printed, a second printing from scans of the riso-printed first round, so the texture is overrun by, for lack of a better term, fuzz. Her forms are round and flowing, rendered in a perpetually-soft pencil (particularly of note is how she draws water in the first few pages, with careful dapples and creases that feel strikingly physical). Her main character, too, is pointedly youthful: their eyes and nose are small and round, and their face is almost entirely smooth with the exception of two permanently-flush cheeks. The resulting feel is reminiscent of Schlosser’s table-neighbor Molly Stocks on the one hand and the French artistic duo Kerascoët on the other.

Kerascoët, it might be said, is a double-edged sword of a comparison. Their Beautiful Darkness, after all, featured an on-its-face similar foray into the dangers of a closed ecosystem. In Kerascoët, the danger stems from the ideological weight of aesthetic — as the wholesome tint of post-Disney fairytales is pitted against the more gruesome beginnings of the storytelling tradition, the contrast is too great to bridge over, resulting in chaos and, ultimately, vacuity.

Schlosser’s intent is neither so lofty nor so nihilistic. Mollusc’s back-cover copy informs us that “[t]o live through a traumatic event is to undergo a transformation,” and that the comic “is a tale of a [person’s] escape from their past and their possible acceptance of the hurt they carry with them,” thus establishing both theme and (ultimately life-affirming) tone. In pursuit of this theme, many of the protagonist’s underwater interactions feature oblique references to trauma: an eel offers words of comfort, while an army of crabs castigates them and blames them for what happened (though it is not said in as many words, it is telegraphed that the trauma is of a sexual nature). But Schlosser—inadvertently, and similarly to Krumpholz—speaks in generalities: the narrative occurs entirely in the present, with no indication of the protagonist’s life outside of their trauma, and as they are carried from one encounter to another they are given neither any defining characteristics nor any opportunities to construct themselves through action. The reader is thus given little in the way of concrete detail — little in the way of emotional recognition.

Though the lack of an issue number on the cover makes this fact hard to tell, the to be continued end-caption clarifies that this is only the first part of a longer story. This choice of presentation appears incompatible with the comic’s ostensible thesis: while gradual development is the very basis of serialization, the drop-off point of the comic at its present form—a cliffhanger of sorts, the cusp of another encounter—gives little indication of the journey still to come.

As a mechanism of distancing, allegory is a means of control: it allows the storyteller to pick and choose not only what to say but the level of opacity as well. But guardedness, for an artist, presents its own dangers. As Mollusc progresses, I can only hope that its creator–a guarded artist, but an able one to be sure–will find her footing in the depths.

Released just in time for Thought Bubble, Another Way Out is a saddle-stitched showcase of three short comics by Carol Swain, published by London archival outfit Dark and Golden. This is Dark and Golden’s second Carol Swain release this year; whereas the first, 2 x Carol Swain, featured two shorts from the second iteration of her ‘90s one-woman-anthology Way Out Strips, the material in Another Way Out—two standalone stories and an excerpt from a graphic novel in the works—is being published for the first time.

There is something to be said for the specific flavor of the lack of polish in Swain’s dialogue. I am generally—and perhaps surprisingly, seeing as I make my living as a translator and proofreader—of the opinion that the meticulous and ‘proper’ punctuation of prose is largely inapplicable to comics dialogue: where most traditional prose (setting aside the more avant garde likes of Joyce and Beckett) operates on the assumption of a proverbial ‘invisible’ stenographer, mediating the narrative from narrator to reader while standardizing legibility, word balloons in comics are a practice of narratorial immediacy, and so it is style, not rectitude, that must take over (in my own writing, when striving for naturalism, the rule I keep in mind is that dialogue should look less like how a given character would email and more like how they would text).

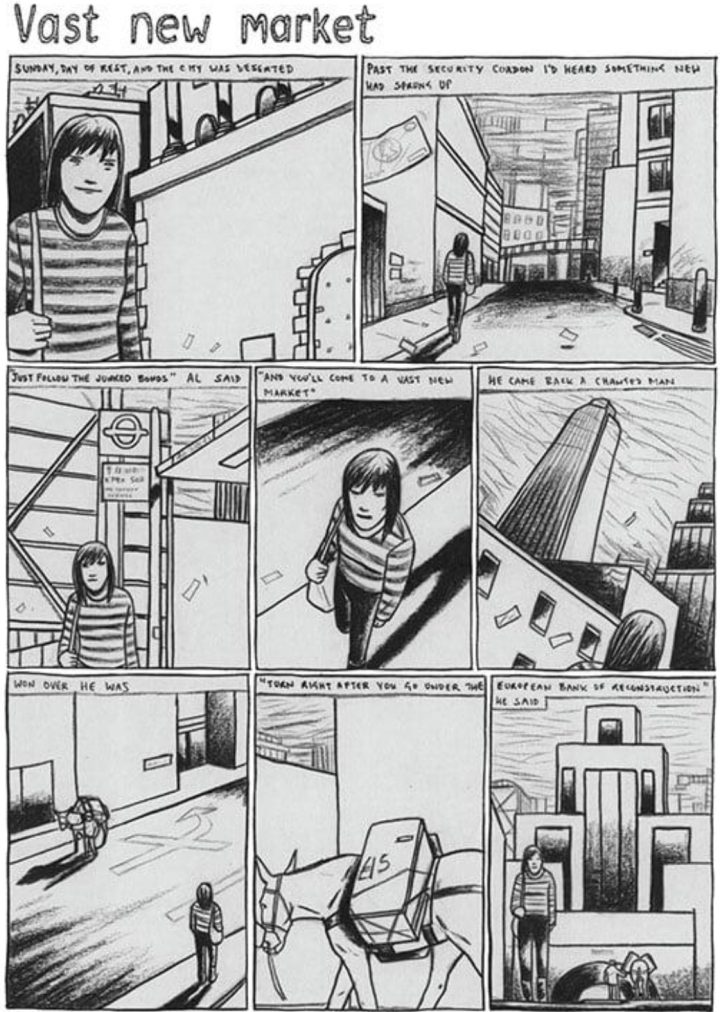

Swain’s approach is colloquial in the extreme. For example, as the protagonist of the first short, “Vast New Market,” looks at an automatic rifle in a street market, the vendor tells her: “It’s dear… fun though, hey imagine the Waco style shootouts!” Grammatically incorrect, to be sure, but, for a cartoonist like Swain, whose work is extremely rooted in naturalist observation, this feels like the only option: bare-bones and unrehearsed. Susan Sontag comes to mind: “It’s not ‘natural’ to speak well, eloquently, in an interesting articulate way. People living in groups, families, communes say little—have few verbal means. Eloquence—thinking in words—is a byproduct of solitude, deracination, a heightened painful individuality.” And communal living is, in fact, perhaps the key component of Swain’s work; her short works in particular—many of which are collected in the Dark Horse collection Crossing the Empty Quarter, which readers are heartily encouraged to seek out—often focus on a singular, fleeting shared moment, achieving precisely that specificity that eludes the previous two cartoonists.

In the case of “Vast New Market,” the moment is one of unresolved menace, reminiscent of Chris Reynolds. The location of the street market is a London gone wrong: police checkpoints are set up in the middle of the city; vendors selling anything from children to “identities” (material signifiers of class or occupation, their previous owners now presumably dead; the rifle falls under “survivalist nut”). As the protagonist wanders the market, she idly asks how much a child would cost; when that proves too expensive, she opts for an identity, and an undesirable one at that: a writer, as embodied by an unfinished manuscript and a typewriter. The cops at the checkpoint throw her manuscript in the air, scattering the pages about, but the protagonist is unbothered, glad of the new skill she “acquired.” Where a more romantic storyteller would reach for some grand statement about the persistence of the human spirit at a time of crisis, Swain complicates matters somewhat with her throwaway imagery: if stories are an ‘escape,’ she seems to ask, then an escape from what exactly — the horrors of the world, or the knowledge that not everyone is as shielded from them as we are?

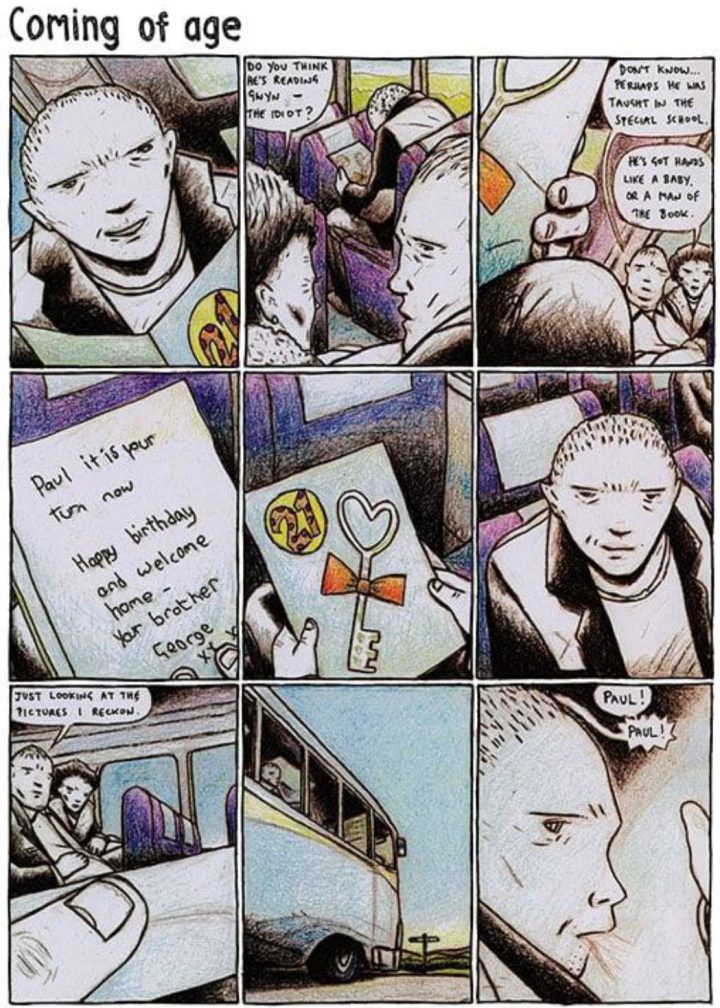

Where the protagonist of “Vast New Market” is inherently a voyeur—she visits the market not out of any necessity but because a friend of hers raved about it—the second story, “Coming of Age,” is a homecoming. As Swain returns to the fictional Welsh village of Llanparc (the setting of all three of her graphic novels), she switches from monochrome graphite to colored pencil, rendering the Welsh countryside in pale, sun-bleached tones. The protagonist, Paul, is a young man with an intellectual disability who returns to Llanparc to work on his family’s farm. What’s interesting is the dynamic between Paul and the world around him. A nearby couple on the bus regards him with a mixture of pity and cruelty, referring to him as “the idiot” and alluding to “the special school,” and as the husband talks to Paul about his upcoming employment, enumerating the duties entailed over the better part of two pages, the reader increasingly feels for Paul: the impression that forms is that he is in over his head. And yet Paul seems entirely undeterred—stoic, even—as his brother hands him his new work jacket. It is on this moment that Swain chooses to end her story, before her protagonist can get to work, and again the reader is forced to rethink their positions: it is entirely possible that Paul is, in fact, doomed without knowing it — but fundamentally it is an assumption sullied by the cruelty of, again, the unaffected spectator.

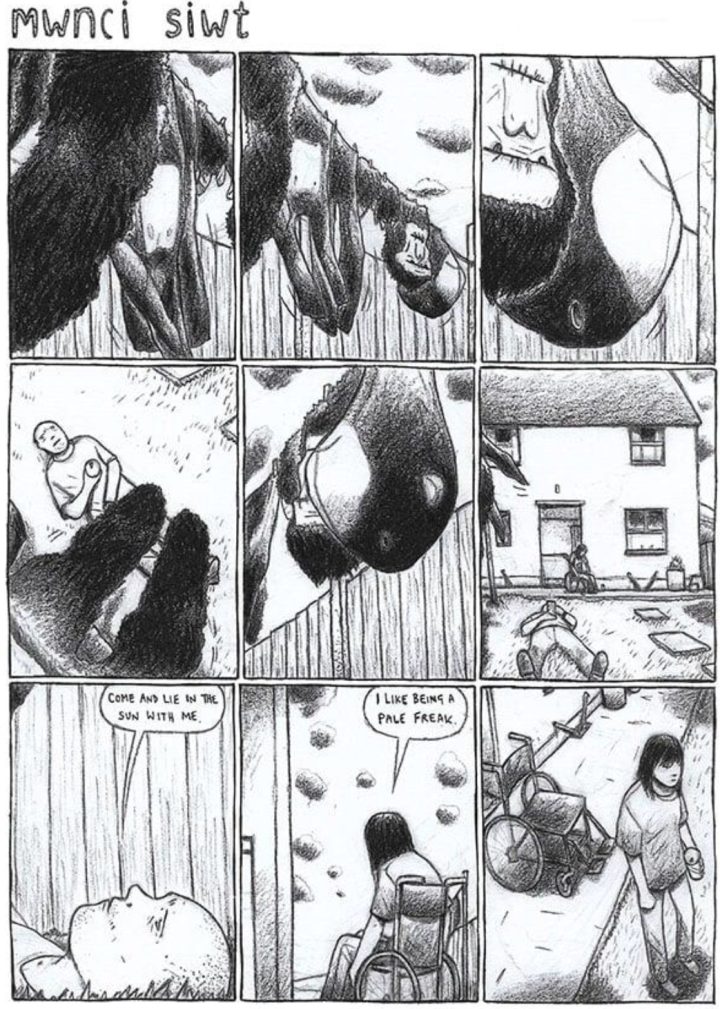

In “Mwnci Siwt” (Welsh for “monkey suit”), which closes out the book, we see something closer to love. A young couple in a backyard, talking: the man, sunbathing on the ground, invites a young woman, sitting in a wheelchair, to join him; behind them, a pair of full-body suits—one of a monkey, the other of a folklore creature—dry out on the clotheslines. Right away, the mood is a strange one: “I like being a pale freak,” the woman seems to rebuff the invitation, only to get out of the wheelchair, indicating that the aid is merely a piece of furniture, and lie down. Their conversation, from this point on, is playful, roundabout: they look at the clouds, then share a fantasy scenario where they permanently sew each other into their suits. Although “Mwnci Siwt” is just a four-page excerpt from a larger work, the piece as it stands is a perfect encapsulation of Swain: two people, one location, and many things left unspoken. Their conversation is profoundly intimate precisely because it is elliptical, the full-body suits beautifully shifting the center of emotional gravity: is it love, to ensure that your loved one never sees you as you are? To ensure that neither of you sees themself as they are? So long as you stick together, perhaps it is love, albeit with some other things mixed in as well.

Swain’s characters all have the same face, or close to it at least: lips thin to nonexistent, eyes sunken and baggy, wrinkles on the brow and around the mouth. What Jose Muñoz accomplishes with his harsh, pooling ink, Swain achieves in her soft-spoken graphites: tired, weathered people in a tired, weathered world. Perhaps it is true, as the song goes, that the Earth has grown tired and all of your time has expired. But, for better or worse, we’re still alive; for better or worse, we’re together, still.

I don’t see people very much these days, really—a shocker, I’m sure—and often conventions, and the days of travel that surround them, are essentially an opportunity to shotgun as much interaction as I can, to regulate the dysregulated. It doesn’t work, really, but it charges those encounters with a unique energy. Some of these faces, I know, I will speak to daily, or at least weekly; others I know I will not speak to before next year’s “good to see you!”. And in the meantime? Whether you come in closer or pull away — life, in flickers, goes on.

The post Enough With The Socializing, it’s Time to Read: Selections from Thought Bubble 2025 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment