In May 2025, first-time author Tessa Hulls was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for her stunning autobiography Feeding Ghosts, making her the only graphic novelist other than Art Spiegelman to ever win the award. Here, she reveals why she never plans to write another book, how traveling solo across the U.S. helped make her a feminist, and why she now refers to this new phase of her life as her “unapologetic triangle era”.

“In Chinese culture, there is a concept of ‘Hungry Ghosts,’ where the spirits of people who did not accomplish what they needed to on Earth are doomed to eternally roam the planet with an insatiable appetite,” nonfiction graphic novelist Tessa Hulls writes in the opening chapter of her Pulitzer-Prize-winning 2024 memoir Feeding Ghosts. “To find peace, I would have to face my ghosts.”

It was in service to this mythic-sounding quest, that Hulls—a peripatetic, world-wandering artist who once biked 5,000 miles alone from Southern California to Maine—put her diverse aspirations on hold at age 30 to pursue this one goal with everything she had. For the next decade, she would learn a new language, travel thousands of miles, and get to know a side of her mother she had never encountered before as she traced the extraordinary story of how her grandmother, Sun Yi—a once-famous memoirist herself—escaped communist China with her young daughter, Rose.

The pair first fled Shanghai to Hong Kong in 1957. Rose later immigrated to the United States in 1970, then brought Sun Yi over to join her in Northern California in 1977. But by the time Hulls was born into their household in 1984, Sun Yi had experienced a full mental breakdown and was a shadow of her former self. A “90-pound specter,” Hulls recalls, “who shuffled around our house in gray Costco sweatpants.” Meanwhile, Rose as a mother had always been to Hulls more of a dangerous force of nature than a nurturer. Someone Hulls sought to run from rather than bond with. “She contained a volatile second self whose actions contradicted her words and the expressions she wore on her face,” Hulls explains. “Thus, I grew up with dual mothers. Loved by a force that was simultaneously shelter from the storm and the maelstrom to be feared.”

Nevertheless, Hulls enlisted her mother’s help as translator, tour guide, and road buddy as the author traveled back and forth to China in a relentless search for both what had made Rose and Sun Yi and what had broken them. The experience changed Hulls’ relationship with her mother forever. This is evidenced by the fact that when I reached out to the now 41-year-old author to set up this interview, she and her mom were spending time together in Alaska, where Hulls lives part of the year when she’s not home in Seattle or traveling.

In the following interview conducted via email, Hulls is as bold, surprising, and engrossing as the swirling, black-ink-saturated pages of her one and only book. “I provide myself as a cautionary tale and say: don’t do what I did!” she tells me below. But anyone curious about what went into the creation of one of the most successful graphic novel debuts of all time may want to take a few notes anyway.

EMILY REMS: It was impossible for me to read Feeding Ghosts and watch you trace the turbulent paths followed by you, your mother, and your grandmother over the past 100 years without thinking about modern research around intergenerational trauma. [The theory that trauma experienced by one generation can biologically impact the way subsequent generations experience and process stress.] Were your own “nature or nurture” ideas about how you became the artist you are impacted by writing this memoir?

TESSA HULLS: I’m pretty sure every idea I’ve ever had was impacted by writing this memoir, but it definitely reinforced my belief that oppositional binaries—nature/nurture, victim/oppressor, truth/fiction—never tell the full story and further degrade the webs of belonging we collectively rely on. When I started this book, I was determined to make it about history, reflecting on my family’s trauma as an objective narrator removed from its reach.

I stubbornly denied the idea of intergenerational trauma because I didn’t like the implications of what its truth might mean. But the years I spent carrying this story instead forced me to confront how much of myself I had shaped around the denial of both connection and duty. I do believe that some people are born as writers and artists. Not in a lofty, great genius sort of way–that shit is heavy; myths collapse beneath their own weight—but in the sense that echoes of stories are in the ether, and sometimes a story needs to be told. So, it goes and finds itself a vessel.

I wasn’t an entirely willing vessel, thus all the frenetic running until I hit 30. But I genuinely believe I was born as an artist and writer because my matrilineal family had an unresolved story that was going to keep consuming all of us until someone had the combination of skills, privilege, and sheer audacity to turn to that story and say, “OK, hold up. What do you actually want? And how do we broker a relationship that gets all of us free? Just because it’s always been this way doesn’t mean we have to keep going like this.” It was a very American power move (Ha-ha).

There’s a remarkable tension within all three generations of women in your family between almost extreme levels of self-reliance and a gravitational pull towards inter-dependence that continually draws you back together. Even after your grandmother’s death. Did the discoveries you made researching this book influence how you balance these sometimes conflicting desires?

In everything I do, I think in triangles: strong structures comprising three points that exist in a state of relationship. Comics are triangles, using words, images, and the synergistic other that forms when they’re combined. I’ve always been fascinated by the invisible other, and in the book, I approached inter-dependence and self-reliance as the two points I could see. I had to make Feeding Ghosts to find the invisible third point that exists as a balanced, integrated synthesis of both those extremes.

Ten years and 4,000 square feet of drawings later, I do feel like I’ve arrived at a new relationship to those conflicting desires and am on a clear path towards building a life that doesn’t have to constantly feel like I’m being torn between extremes. I spent my 20s as a cowboy, then gave literally the entirety of my 30s to being a good Chinese daughter by making this book. I’m entering my 40s feeling free of the weight of those oppositional roles. It’s my unapologetic triangle era.

Only two graphic memoirs in history have ever been awarded the Pulitzer Prize, Feeding Ghosts, and Art Spiegelman’s Maus—the story of his father’s memories of the Holocaust—that was awarded in 1992. In both books, the extraordinary blend of innovative artwork and vivid storytelling made global turmoil from the past come to life in new ways through the eyes of the children and grandchildren of those who experienced those horrors firsthand. Did you have any exposure to or experience with Maus before you wrote your own memoir? Do you see Feeding Ghosts and Maus as part of the same literary lineage or storytelling tradition?

Like a lot of artists my age, Maus was the first graphic novel I ever read—but I was too young to fully appreciate it. When I started Feeding Ghosts, some part of me had the very good sense to not go back and re-read Maus until I was almost finished. When I did finally re-read it, I was absolutely blown away. Not only by the brilliance of the work, but also by the extent to which I’d mirrored the structure of a child following a parent around with a notebook, trying to extract an emotional story by excavating the negative space of what wasn’t being said.

If I’d re-read Maus while I was still figuring out the structure of Feeding Ghosts, I think I would have been paralyzed by the fear that I was copying something. But one of the interesting things about doing so much research into both intergenerational trauma and the craft of memoir was seeing how artists and writers use the same language and devices to render shared history. There are uncanny parallels that emerge in creative works when an entire generation describes collectively held wounds.

One of the first books that really helped me see this was Susan Griffin’s A Chorus of Stones: The Private Life of War. Artists and writers serve as collective memory keepers. There’s a Kay Ryan poem that goes: “Forgetting takes space./Forgotten matters displace/as much anything else as/anything else. We must/skirt unlabeled crates/as though it made sense/and take them when we go/to other states.” Spiegelman and I both grew up bruising our shins against the invisible crates of the history our families didn’t talk about, and we went on to make books that broke the fourth wall to directly confront and interrogate that history.

Maus feels like Feeding Ghosts’s incredibly cool, rebellious older brother, who kicked open a door (probably while wearing a leather jacket and smoking a cigarette) to let a whole generation of new voices in. Feeding Ghosts could not have existed if Maus hadn’t blazed the way.

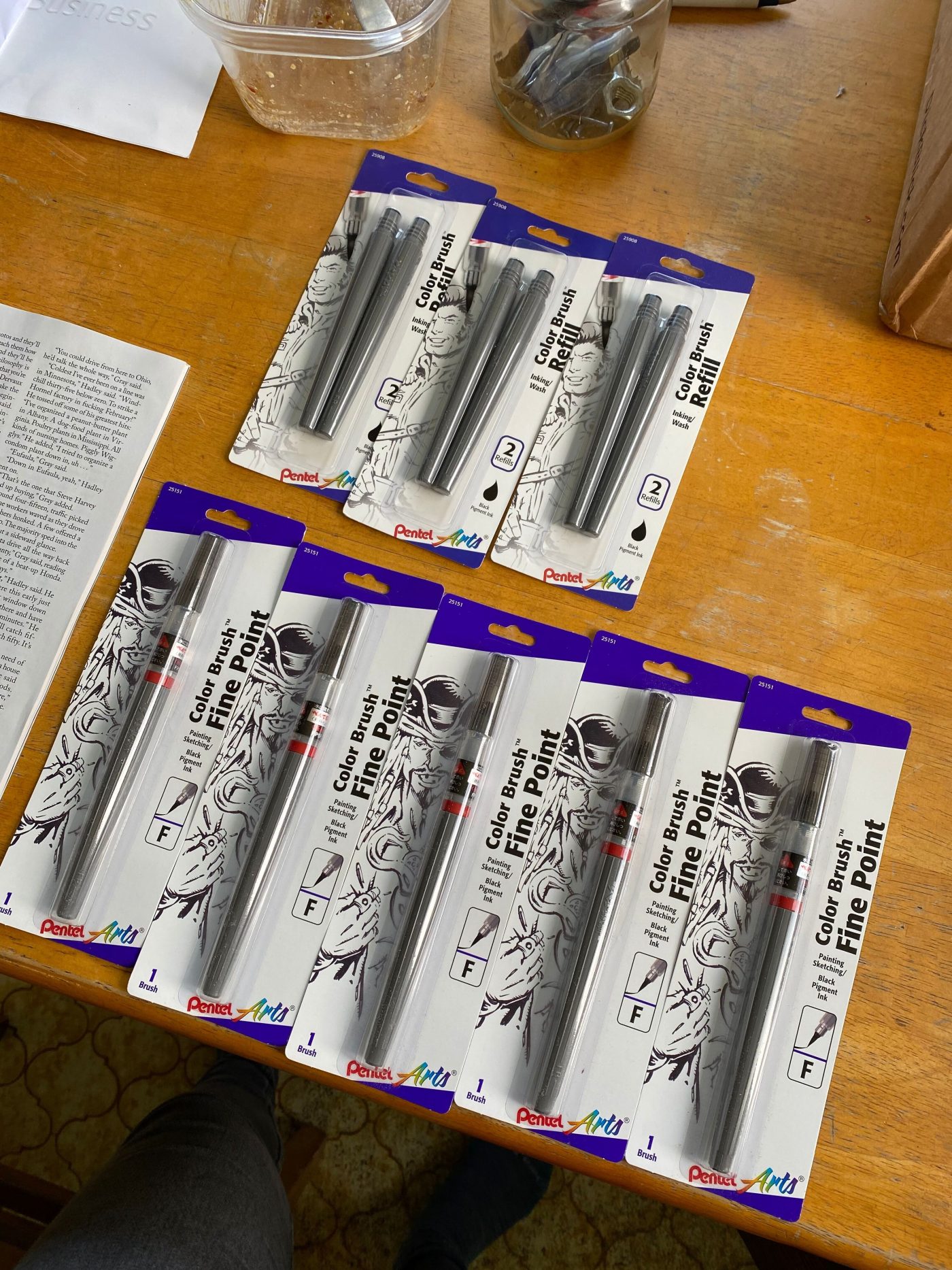

Talk me through your art-making process for Feeding Ghosts. You use so many innovative techniques to bring clarity and context to a story that spans multiple decades and continents. What materials did you use (both analogue and digital)? What did a day of work look like? Did you write out the whole memoir first and then illustrate it? Or were writing and illustrating done concurrently?

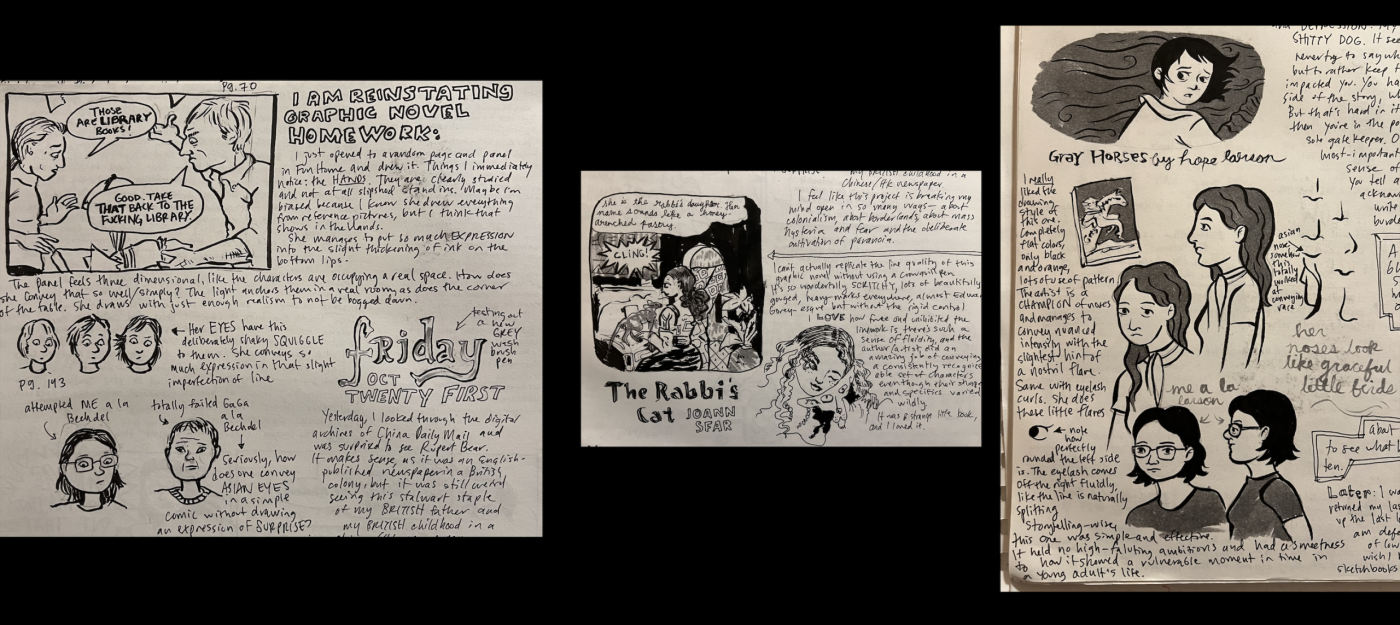

Oh God, I don’t even know where to start with that question except to provide myself as a cautionary tale and say: don’t do what I did! I came up as a visual artist and my most established medium was as a painter working in gouache. I always wrote in my sketchbooks to find the structure of my ideas, but I considered that side of things the invisible armature. As more people got glimpses behind my verbal curtain, however, they started telling me I was a writer and giving me assignments as one. So, that side of what I do grew very organically, mostly in the form of interviewing other artists and writing about their work.

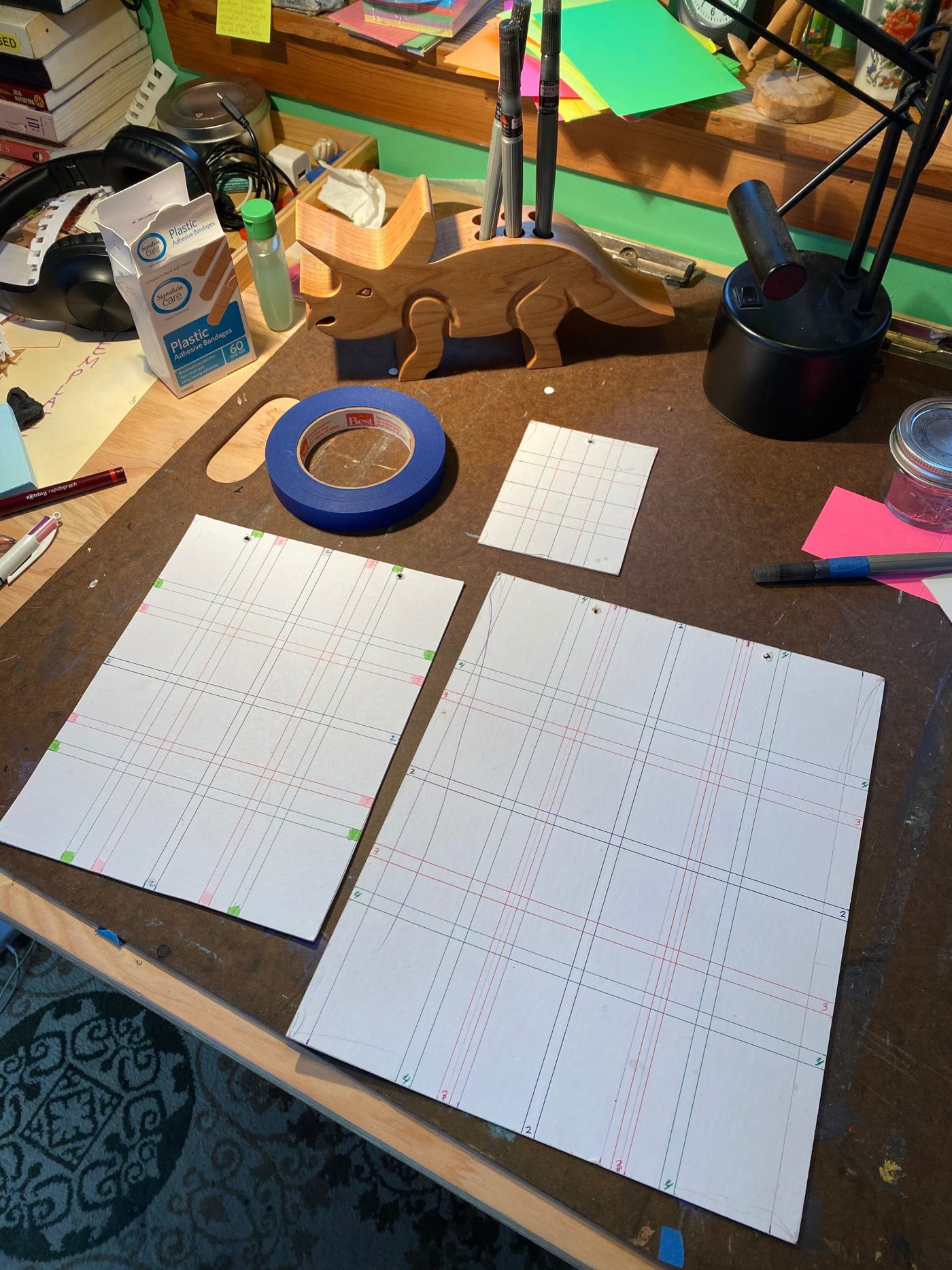

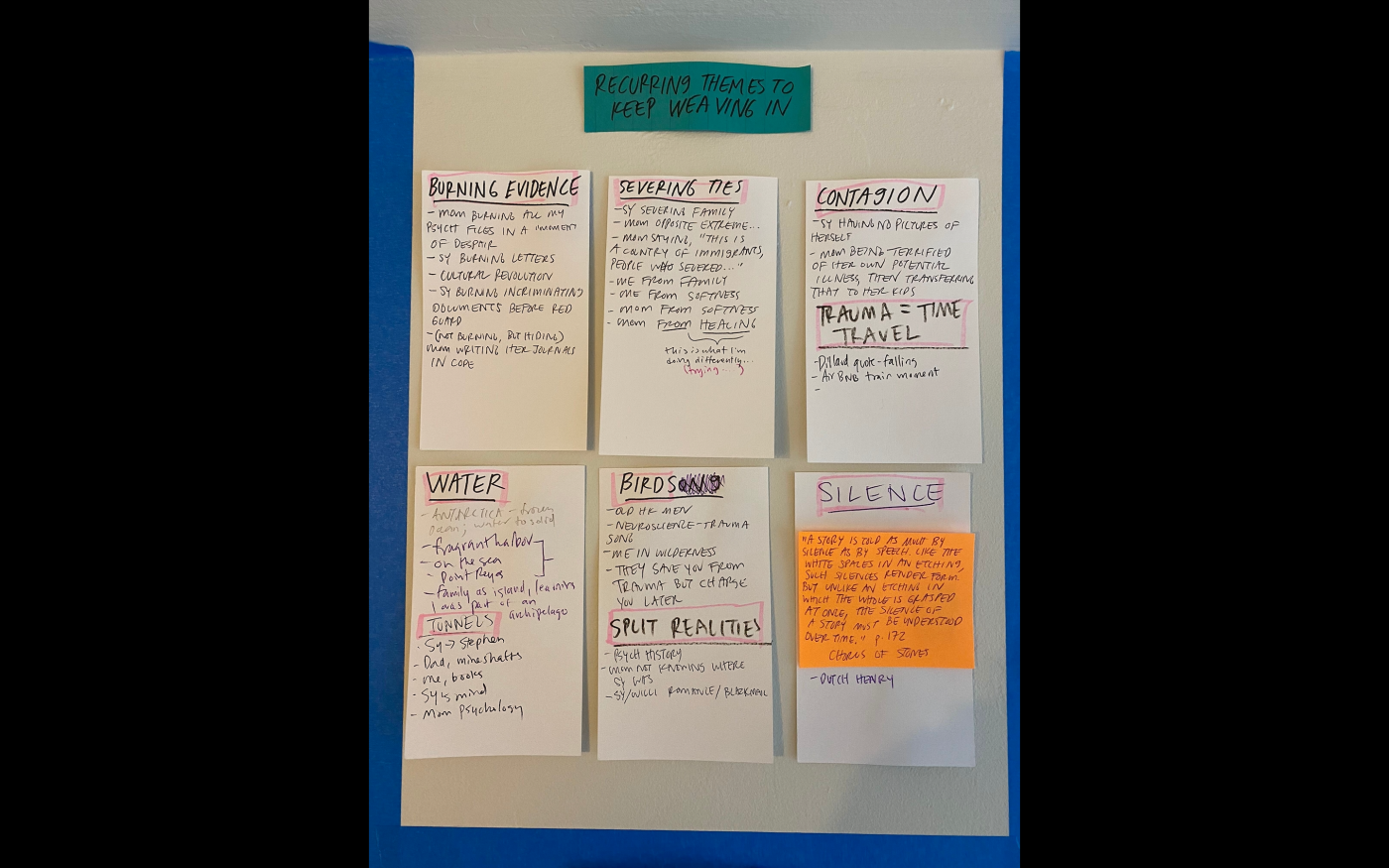

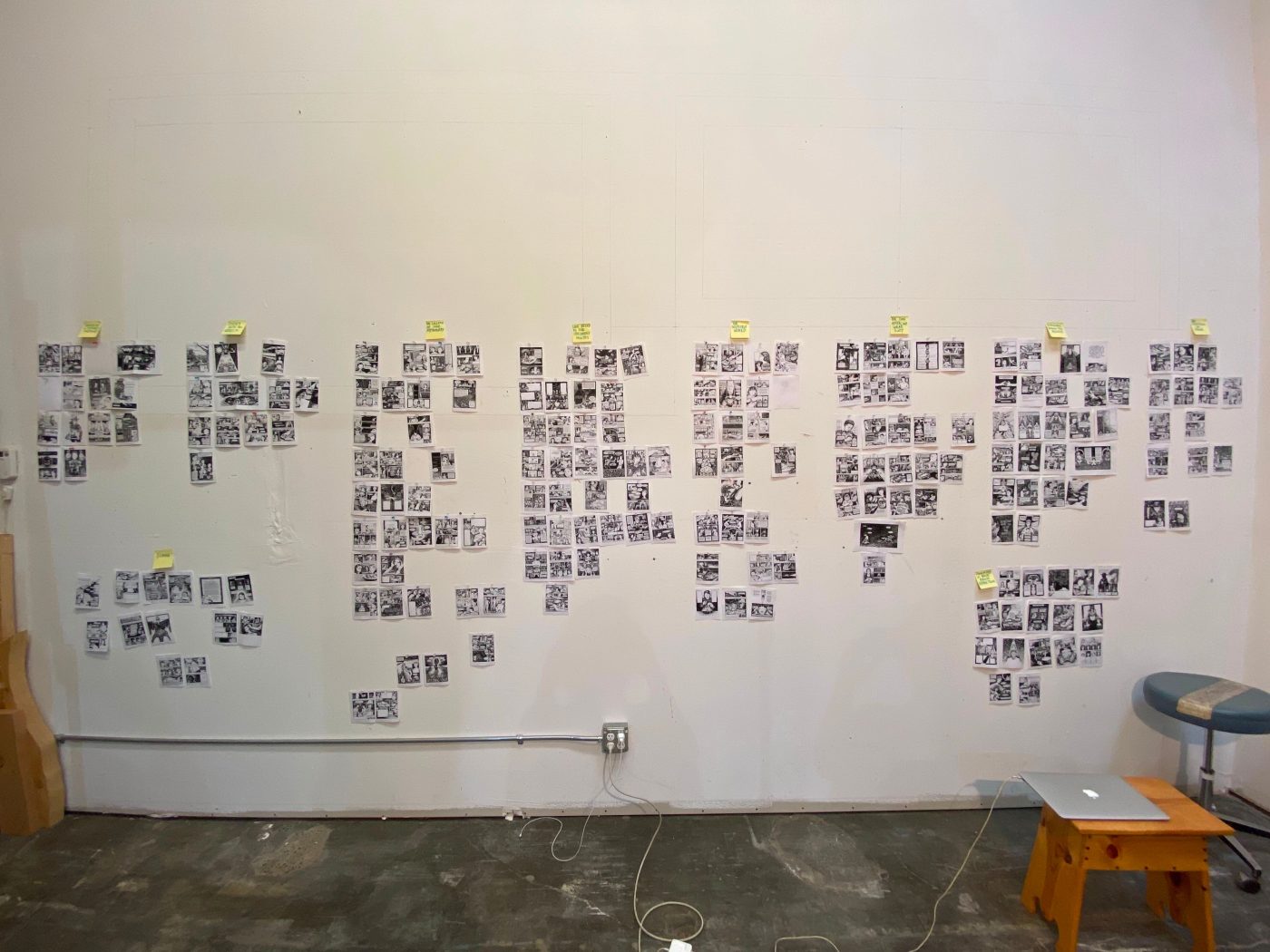

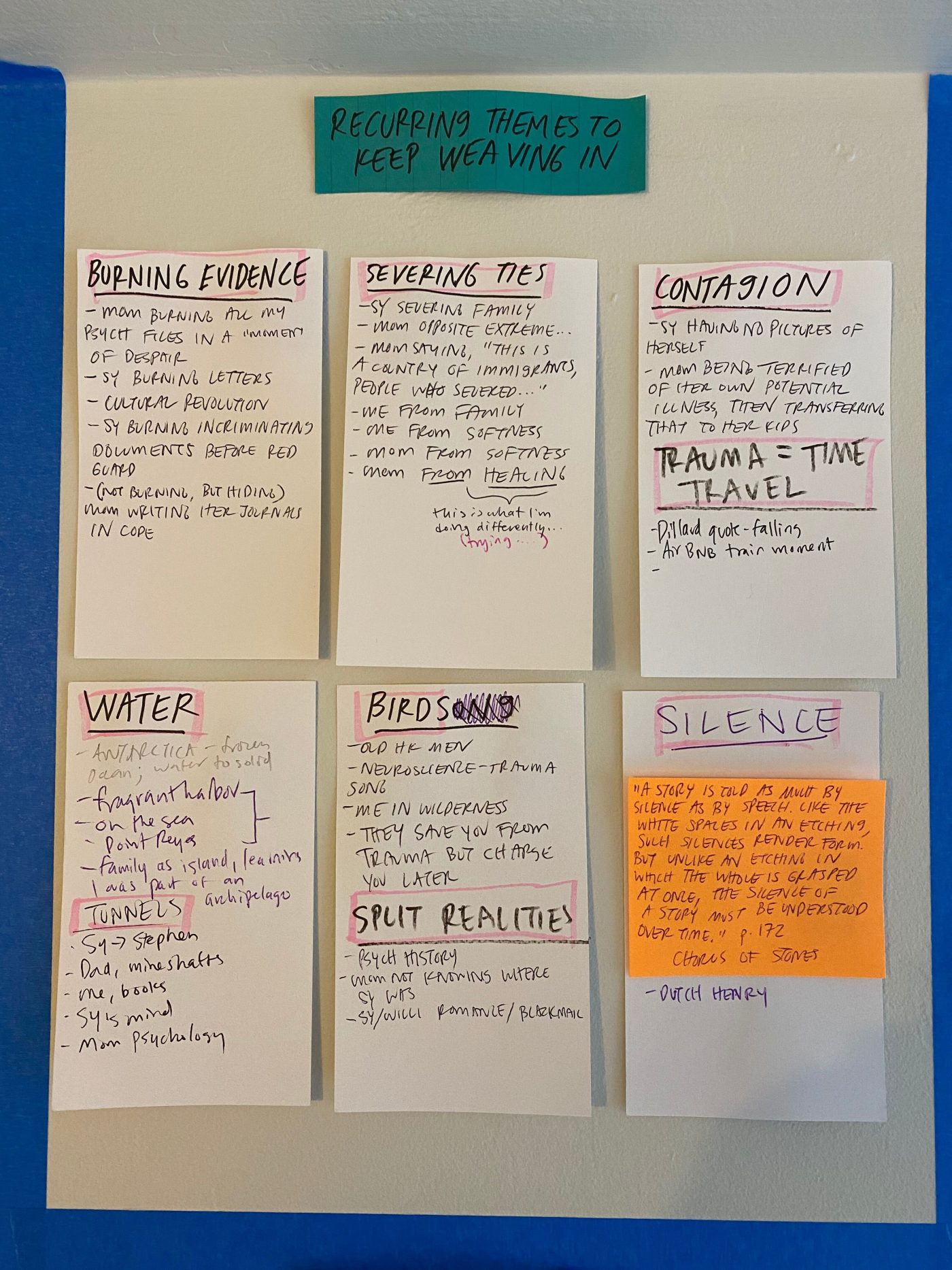

I’ve always worked in at least half a dozen different creative mediums and approach each project as a relationship, where I ask the story I’m exploring what form it needs to take. With Feeding Ghosts, my early days of finding the structure involved taking sheets of 18”x24” paper and covering them in hybrid, free-form words and images until I had a whole table full of them. Then I’d go back and circle things that looked like they kept coming up. Sometimes the same themes and ideas would shift between words and images. Even when I was working on final pages, I often didn’t know if something would come out written or drawn.

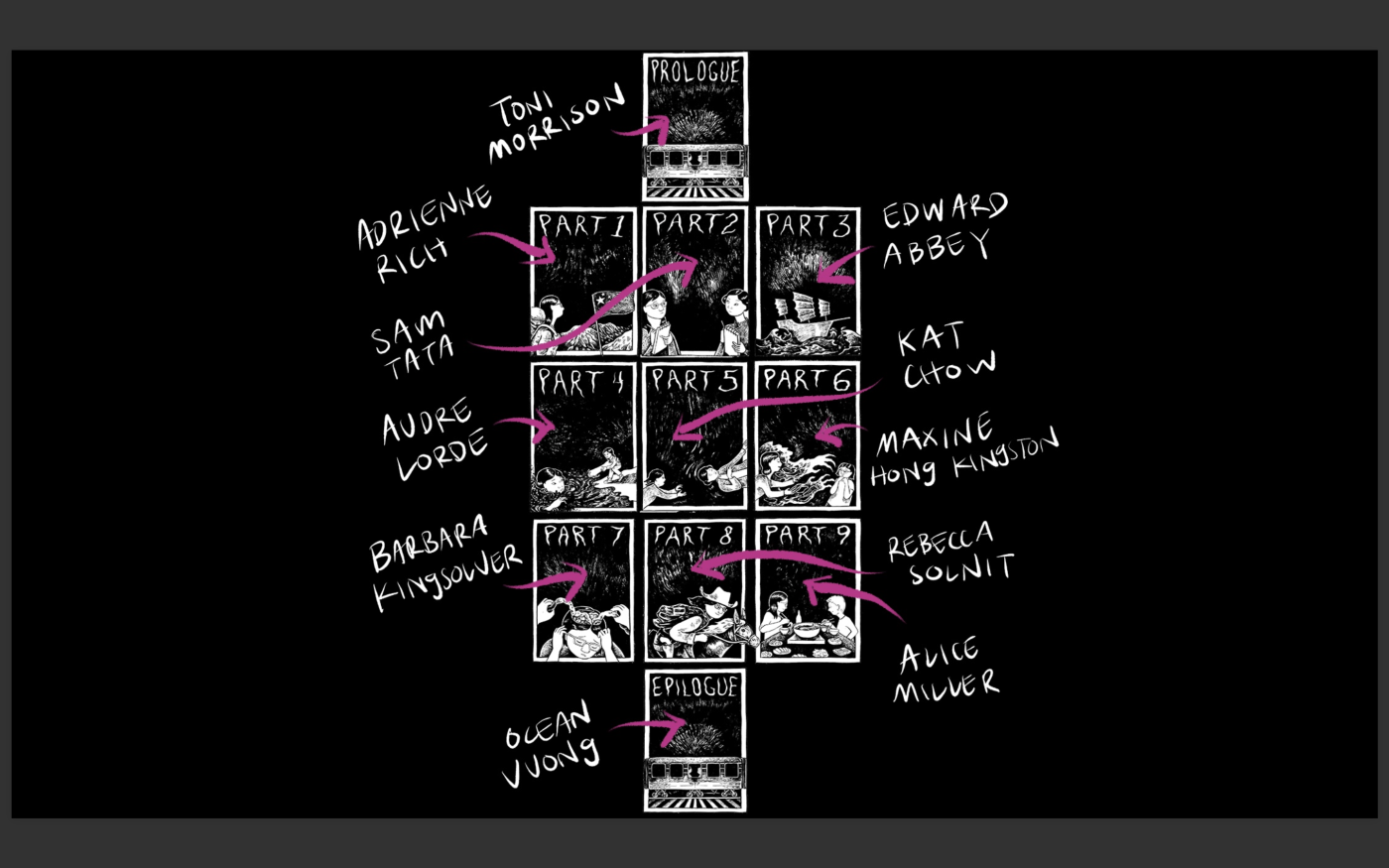

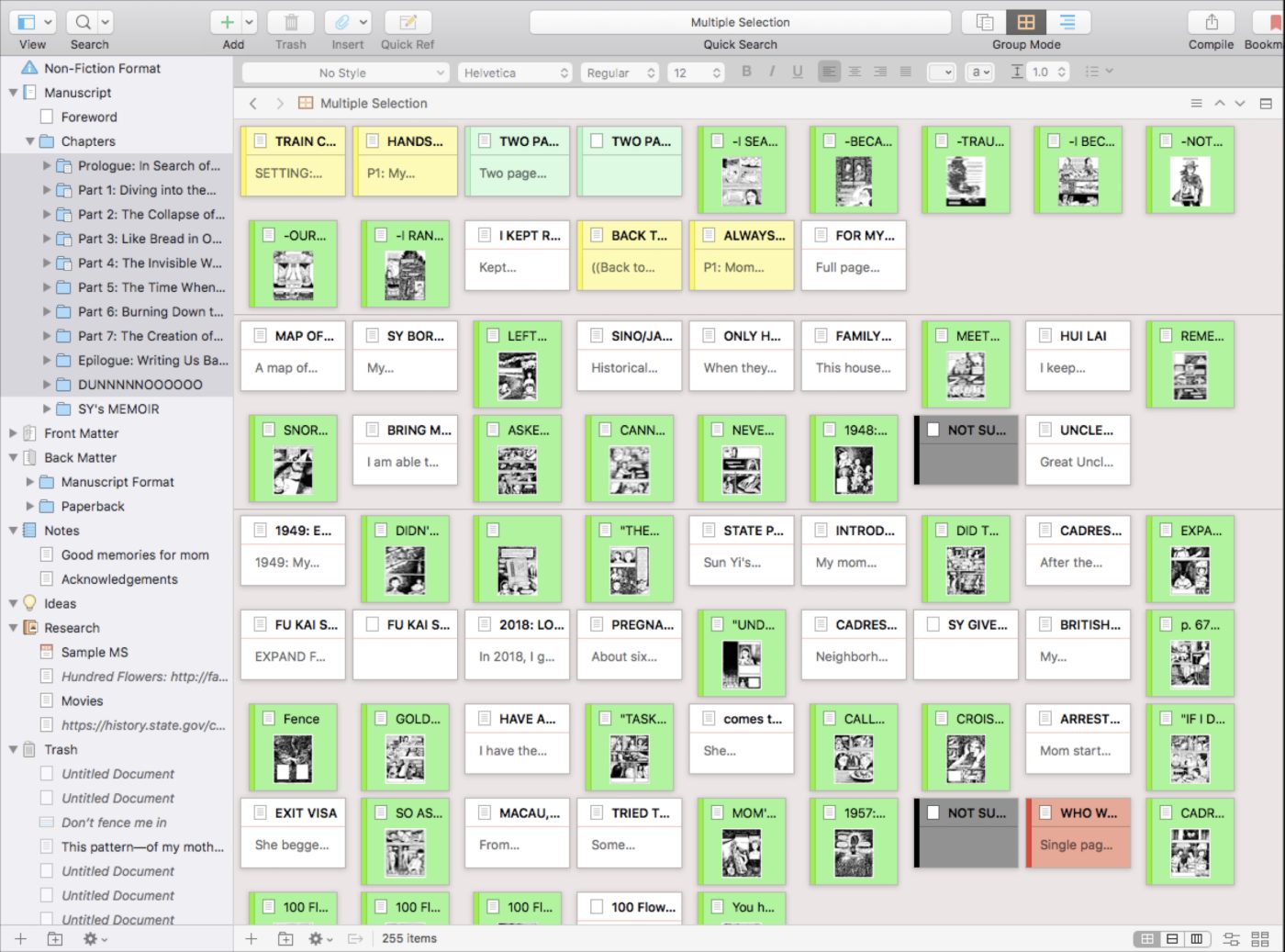

I never scripted, thumbnailed, or penciled. Instead, I first wrote the whole book as a 10,000-word creative nonfiction essay, where the epigraphs that start each section served as the anchor points of the structure. I then used Scrivener to break apart that essay so I knew approximately how much content I would try to put on each page. (Literally: there would be three pages where it would just say “Explain Cultural Revolution in three pages—here, here, and here.”)I then printed that file into a three-ring binder and would flip through it until I came across a page I maybe knew how to turn into a comics format, and would then go straight to final inking, sometimes not even knowing what all the panels would contain. I therefore, drew the entire book simultaneously until it came into focus as a whole.

Basically, I made a 4,000-piece jigsaw puzzle by carving each piece by hand, and told my editor she was just gonna have to trust me that it was gonna fit. And against all odds, it…did? All the text boxes and speech bubbles were digital layers added at the end, so the way I edited the text involved copying and pasting the text from the finished pages into a word doc, which was when I found out how many words it was (it was about 60,000—way more than most graphic novels). We did line-item edits from solely that text document.

The book was a constant act of translation between word and image, and I think that kept the final product unusually—and maybe pathologically—dynamic. There was never a point at which I got to just ink on autopilot, and I think that served the book as a whole. But it sure as hell contributed to why making this thing psychically flayed me.

I was reading Feeding Ghosts through a feminist lens because that’s how I read everything! In all three generations of women in your family, everyone bucked societal expectations of what a woman was supposed to be in their own ways. Most notably, your grandmother published a bestselling memoir in 1958 that was banned in China. And now, 67 years later, your own bestselling memoir was awarded a Pulitzer Prize and was written in a genre (graphic novel) that is considered notoriously male dominated. In the book, you refer to yourself as someone “undeterred by being born into both the wrong gender and the wrong century.” Do you consider yourself a feminist? Did you encounter any sexism or other confining societal expectations that you needed to push past to make what you wanted to make?

I very much consider myself a feminist, but I deliberately avoid leading with that word. To explain: the genesis of pretty much all the most important things in my life can be traced back to bike rides. In 2011, I biked 5,000 miles alone from Southern California to Maine. The experience of being told every single day that it wasn’t safe for a woman to travel alone, and that I was incapable of doing what I was in the process of actively doing, reinforced my preexisting tendency to respond to being told something is impossible by saying, “Hold my drink.”

Since my own experiences weren’t considered a viable counterexample, I got back from that trip and marched myself to my other favorite wilderness—the library. I started researching obscure historic examples of women who, when confronted with the multiple choice options available to them, said, “None of the above.” That bike ride unwittingly led me to a side career giving illustrated lectures about female trailblazers in the late 1800s.

I first developed that lecture for a speaker series called the Academy of Reason and Wonder. Knowing that my audience was a bunch of liberal artsy people in Seattle, I called it “Fucking the Patriarchy in the Early 1900s.” I later joined the Humanities Washington Speakers Bureau and traveled throughout rural communities in Washington giving the same lecture, and they changed the name of my talk to “She Traveled Solo.” At first, I was very against this and felt like it was diluting what I was trying to say. But I completely changed my tune, because it made me see how leading with incendiary language immediately means your message is only going to reach the people who already agree with you. And I am less than uninterested in preaching to the choir. The content of my talk didn’t change at all, but changing the title allowed the conversation to happen, and I learned something from that.

Nuance is the hill I choose to die on. Having spent well over 20,000 miles biking alone all over the world, talking to people about their lives, I relish the opportunity to engage in true, open-minded dialogue with people whose perspectives are unlike my own. The internet has destroyed our ability to sit in compassionate disagreement, and I think a huge part of that starts with the way we’ve been trained to preemptively sort ourselves into warring factions with our language choices.

So yes, I am a feminist; but I like to be subversive as fuck, and I can’t do that if I push confrontation from the jump, so I don’t call myself one. It goes back to creative writing 101: show, not tell.

Your memoir came out just as the U.S. began veering dramatically in a radically anti-immigrant direction. How has your experience researching and documenting your own family’s immigrant experience for this book impacted your political views? What are your current political views and how have you chosen to express (or not express) them?

My first research trip for Feeding Ghosts coincided with the 2016 U.S. election, and I was at the Hong Kong history museum in an exhibit about the Japanese occupation as the votes were coming in. The exhibit was designed as a bomb shelter, with the sound of simulated blasts piped in through speakers. The resonance of that moment felt almost comically heavy handed—but I had a sense of watching the past repeat itself, and that happened many times over in my research. From the current Trump administration’s adamant denial of both science and physical reality to the specific language employed to denounce problematic thinking, everything about how I view the current moment is affected by the fact that I was immersing myself in Chinese history between 1927 and 1976.

China’s Great Leap Forward, where Mao declared that China would turn its entire population towards bolstering steel production to prove a pissing-contest point to the global economy, ended up causing irreparable damage to the environment and mass starvation that led to millions of deaths. Watching the Trump administration deny climate change and undo the shift to renewable energy to prop up the dying industries of coal and fossil fuels, all while gutting SNAP benefits and subsidized health coverage—welp. It doesn’t take much to draw a direct line there.

I am direct in my personal political views, but I have also come to be something of a conscientious objector around social media and don’t engage with politics there. Yelling our beliefs into the void on echo-chamber platforms designed to commodify outrage just further sorts us into rigid ideological camps with no path to reconciliation. I’m much more interested in asking: What brought us to this point, and how do we de-escalate?

On your website, you say you are “completely sure” that you are never making another book. Is this really still true? If so, why?

I’ve never been more sure of anything in my life! I’ve always been someone who reverse engineers how to reach something, starting with the destination and working backwards. When my family’s ghosts tasked me with telling this story—literally, they hijacked a landscape and made it speak out loud to me, saying “Someone has to feed the ghosts”—I laid out what I thought would be a three to five year plan of the tools, skills, resources, and professional access I’d need to pull that off. And I then went about creating an entire bespoke career to accomplish that one singular task.

Feeding Ghosts never came from a place of desire: I made it from love and duty, with the goal of healing my relationship with my mother. But at no point did I ever want to make a book, and I have never wavered from that. I’m an extremely multidisciplinary artist who likes to make work from a place of being in the world, and I see each project I take on as a relationship that chooses the medium it wants to come out in. The scorched-earth commitment that Feeding Ghosts required of me felt like turning my back on the core of who I was for almost 10 years, and it distorted my relationship with my creative practice from one of refuge to one of deep pain.

I’ll use a Lord of the Rings metaphor: Frodo never wanted to be tasked with death marching the damn ring across Mordor. But the task fell upon him and he saw that no one else could do it, so he did it. And he didn’t take any breaks for self-care or rest along the way because those things would only have prolonged the pain of the journey. The only way to be free of the burden was to finish the task. And he did, but it almost killed him.

The metaphor breaks down a bit because when Frodo was lying mostly-dead on the flanks of Mt. Doom, he didn’t have to field the utter surprise of a bunch of national awards triggering a deluge of people saying, Surely all this recognition had changed his mind, and he was going to march another ring across Mordor, and what was his next ring going to be? But I think you get the picture of why I am very, very sure I am not doing this again.

To be clear, I will absolutely continue to be an artist and a writer, and to use comics as a powerful tool to convey complex ideas from a place of deep emotional resonance. But never again a book. I refuse to make myself that isolated ever again.

You’ve written that instead of writing another book, you plan to “instead fuse [your] wilderness and creative lives by becoming an embedded comics journalist working with field scientists, Indigenous groups, and nonprofits doing work around ecological resilience and climate change in remote environments.” How is this plan progressing? What projects have you undertaken in this regard and what’s coming up next?

This plan is progressing, and the current limiting factor is my own unavailability. I tend to do things to extremes and have been way too much of a leaf on the wind for more than two years. Thus far, I’ve climbed 2000-year-old sequoias in Yosemite and have been dropped off by bush plane to packraft the Marsh Fork of the Canning River in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and I’m looking forward to getting in the studio to really flesh out those stories.

But I have the strong intuition that my professional life is drawing me towards being of service to rivers. I just read Robert Macfarlane’s Is a River Alive? during a week off-grid in the Rogue River Wilderness, and I interviewed Orijit Sen for a new edition of River of Stories (forthcoming from Kaya press), and in ways both literal and metaphoric, rivers have been talking to me for years. The Elwha dam removal, the [public art project] “Duwamish Revealed,” the University of Washington’s “Waterlines” [initiative]—rivers are pulling me into the current of something new and collective. I don’t know entirely what it is yet, but I trust it. And that somatic place—of being called by a horizon I can’t fully see—is where I thrive.

In the opening chapter of the book, you write, “In Chinese culture, there is a concept of ‘Hungry Ghosts,’ where the spirits of people who did not accomplish what they needed to on Earth are doomed to eternally roam the planet with an insatiable appetite. Trying to quell a starvation with no bottom…. To find peace, [you] would have to face [your] ghosts.” Do you have a sense of how your future ghost is doing in the time since publishing Feeding Ghosts? On a spectrum stretching between “Hungry Ghost” and “Peace,” where would you say your spirit is living these days?

Ooh, I love this question! Since we’ve covered how I feel about binaries and triangles, I’m gonna say that on a spectrum from “Hungry Ghost” to “Peace,” I’m on the invisible third point of “Dynamic Equilibrium.” In physics, there are three types of equilibrium, which you can picture by imagining a ball. In neutral equilibrium, the ball is just chilling on a flat plane. It’s not going anywhere because no forces are acting on it. In static equilibrium, the ball is at the bottom of a U-shaped valley, motionless because the form of the environment means it can’t go anywhere. And in dynamic equilibrium, the ball is perched on the precipice of a hill, always needing to enact adjustments to maintain its balance.

It’s a very active state of balance that requires all your senses. That’s where I am, and it feels damn good.

The post Ghost Story: an interview with Tessa Hulls on her Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic memoir appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment