Headlines such as “Jean-Christophe Menu in A3” and “Menu revives the 30/40 collection”, from the French dailies Libération and Le Monde respectively, point to one of the major events on the French comics scene in 2025. The emblematic 30/40 collection, originally created by the publishing house Futuropolis in the mid-1970s, has been revived under the banner of L’Apocalypse – the publishing house Menu founded after his departure from L’Association – thus continuing that legacy. A piece of comics history has returned. The first to be featured in the new 30/40 series: Jean-Christophe Menu himself.

But first, it is necessary to keep the concepts apart. Futuropolis, founded in 1974 by Étienne Robial and Florence Cestac, has no connection to the current publisher of the same name that churns out tame adventure comics with political overtones. The latter is a classic case of brand appropriation. The original Futuropolis was a key player in the vibrant and innovative French comics scene of the 1970s. With strong support from influential magazines such as L’Écho des savanes (1972), Métal Hurlant (1975), and Fluide Glacial (1975), Futuropolis symbolized a shift toward an adult readership during what has often been described as the golden age of French comics. In her autobiographical album La véritable histoire de Futuropolis (2007), Cestac shows how she and Robial worked to change perceptions of comics in France and elevate the medium’s status by exhibiting original pages in galleries, organizing signing sessions with artists, publishing hardcover books in larger formats, and placing them in the art sections of Parisian bookstores.

But perhaps it was the 30/40 collection that most clearly embodied the publisher’s ethos: oversized books that decisively broke with the standardized French album format (think Tintin and Spirou). The name of the collection referred to its dimensions – 30 cm by 40 cm (approximately 11.8 inches x 15.7 inches), also known as A3. The format was chosen because it corresponded to the dimensions of a standard page of original comic art commonly used by cartoonists at the time. This allowed the artwork to be reproduced as a facsimile at its original size, rather than in a reduced format.1

Over a span of just over twenty years, between 1974 and 1993, twenty-two volumes of 30/40 were published, each one devoted to a single artist. Among the featured names were Moebius, Tardi, Joost Swarte, Robert Crumb, and Chantal Montellier, as well as less familiar figures in France such as Vaughn Bodē, Jeff Jones, and Bernie Wrightson. For several foreign artists, 30/40 marked their major entry into the French-speaking comics market.

The design was innovative precisely in its simplicity – restrained and understated – only showing the name of the cartoonist in question. This approach can be seen as emblematic of Robial’s editorial philosophy, with a strong emphasis on authorship and, more broadly, a meticulous attention to the book as a crafted object. All of which is said to have greatly inspired Menu’s own practice.2 And now the time has come for Menu himself to be consecrated, as The Comics Journal reported in 2024, upon the direct request from Robial.

“As I’ve said and repeated, the first idea was not to make a 30/40 of myself!” Menu explains from his home in southeastern France. “I suggested to Robial that we relaunch the collection, which ended in 1994 with the demise of the real Futuropolis. And Robial agreed that L’Apocalypse could revive 30/40 under his artistic direction. But I was thinking of cartoonists from Robial’s or Tardi’s generation – those who are now in their seventies or eighties — who never had ‘their’ 30/40 during the original run. So when he said the first new one would be a Menu 30/40, I swear I wasn’t prepared. I couldn’t say no, but… you know the French word trac? It means stage fright. Well, I had trac! I couldn’t draw a line for one or two years.”

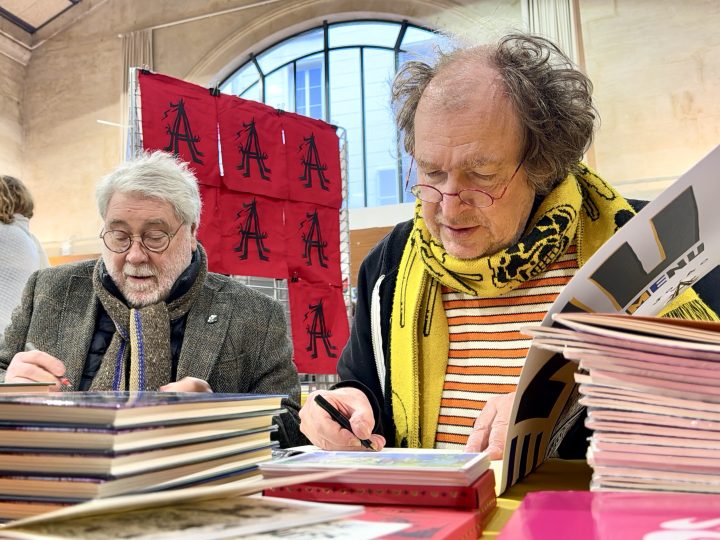

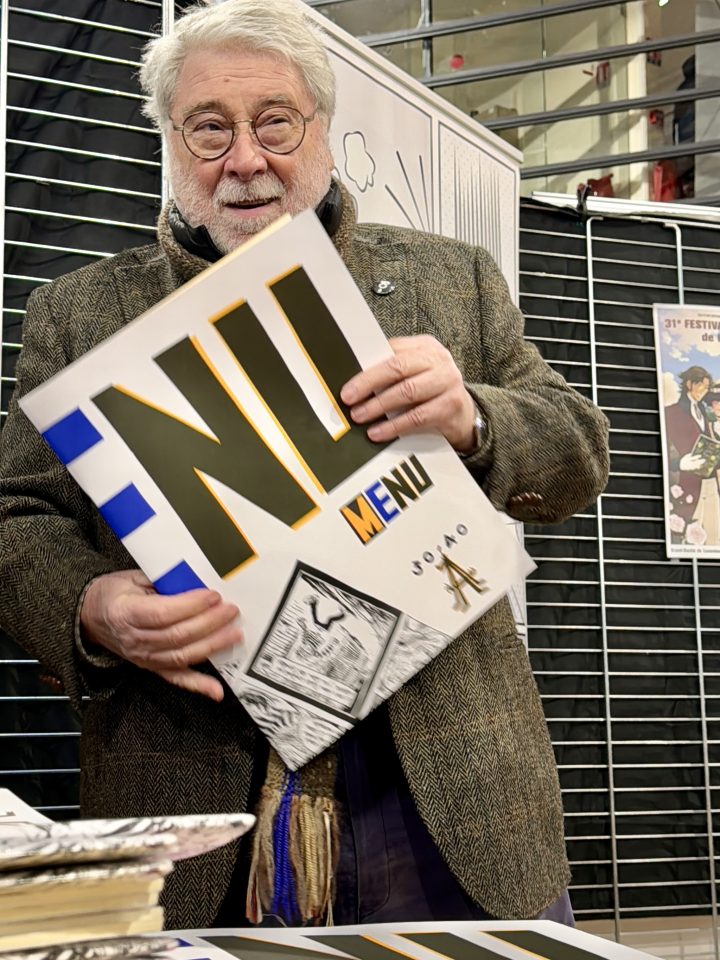

Étienne Robial holding the latest installment in his 30/40 series. Photo: Matthias Bourdelier

One possible explanation for Menu’s creative paralysis may lie in the significance he attaches to receiving his own 30/40. Anyone even vaguely familiar with his work knows the profound influence that Futuropolis and Étienne Robial have had on him. During the emergence of the French nouvelle bande dessinée movement in the 1990s, Menu frequently emphasized – not least in pamphlets such as Plates-bandes (L’Association, 2005) – the pioneering role of Futuropolis as a vital source of inspiration, demonstrating years earlier that an alternative path for comics was possible. In short, looking backward could also be a way forward.

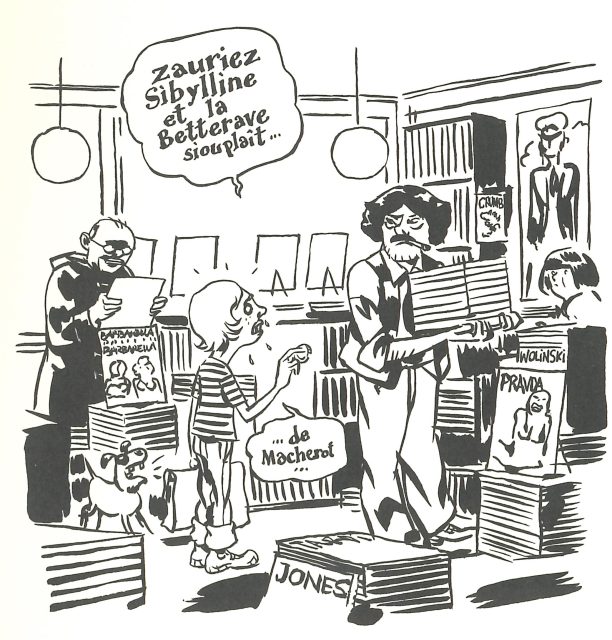

Moreover, the two have collaborated in various capacities since the mid-1980s, but their relationship began much earlier, when Menu was still a child. According to the preface of Menu 30/40, their first encounter occurred when a twelve-year-old Menu visited the Futuropolis bookstore in Paris to spend his weekly allowance on comics by Raymond Macherot. ”I was in the Futuropolis store, located in the fifteenth arrondissement of Paris, looking for Sibylline et la Betterave by Macherot, because the store also sold secondhand and ‘Belgian’ collectors’ items,” Menu remembers. “I’m not sure it really was Robial I spoke to, but let’s print the legend! He didn’t have the album, anyway. I eventually found it later in Amiens, brand new in a regular bookstore – I thought I was dreaming, since it had been out of print for years. Those were pre-internet days.”

Ten years later, when Menu was an aspiring cartoonist, he and his friends submitted work to Futuropolis’ Collection X, a series launched in 1985 and run by Jean-Marc Thévenet. The collection consisted of small, hardcover albums of about twenty-four pages with the stated aim of giving a platform to new talent (although established artists such as Loustal, Willem, and Cestac also contributed). Menu, together with future L’Association co-founders Stanislas, Mattt Konture, and Mokeït, each published a title in the series – Menu’s first professional publication appearing in 1987 with Le Portrait de Lurie Ginol. “We didn’t deal directly with Robial himself,” Menu recalls. “But we would see him passing through the offices – grumpy and impressive.”

Later, Robial sought to bring together the young artists from Collection X in an anthology. Menu was chosen to lead the project due to his experience editing his fanzine Le Lynx. This initiative resulted in Labo, a one-off, unnumbered issue, including comics by, among others, Killoffer, Lewis Trondheim, Mokeït, Stainslas, Mattt Konture, David B – all of whom would found L’Association together with Menu in 1990. “And Robial always remained a kind of godfather to L’Asso”, Menu says. “We became even closer during the later conflicts [that led to Menu’s departure in 2011] – he took my side – and he eventually became a partner at L’Apocalypse.” In that sense, the two now gray-haired heavyweights’ renewed collaboration by breathing new life into the 30/40 collections carries an unmistakable sense of the circle closing.

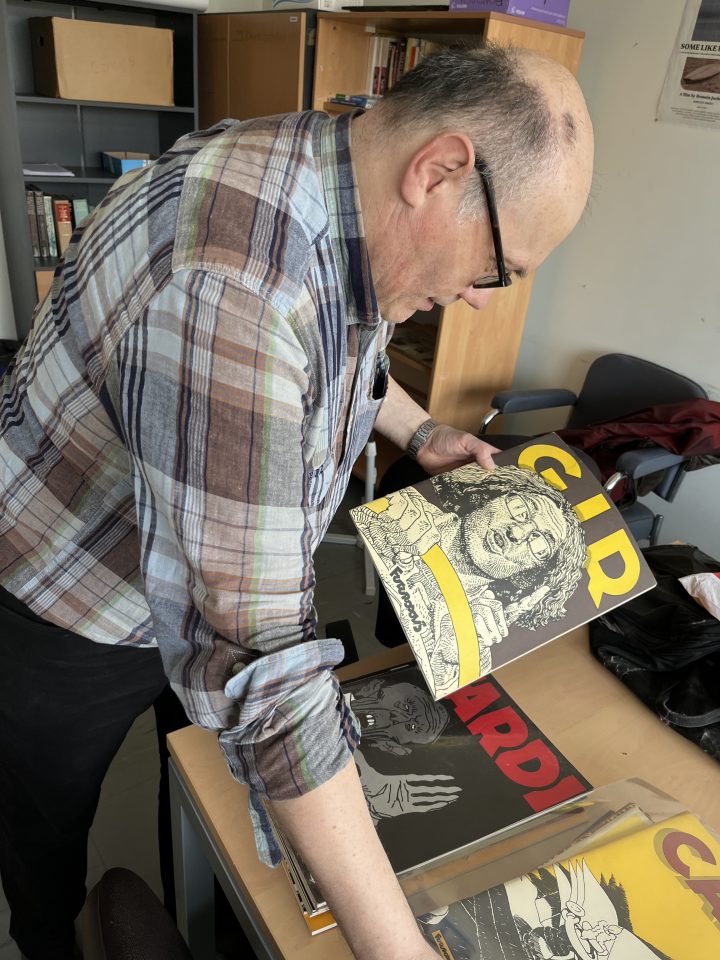

The new issue – the first in roughly thirty years – was on sale at the most recent Angoulême Festival. Among those attending to get a copy was Jean-Paul Gabilliet, professor of comics history at the University of Bordeaux Montaigne, who has been a devoted reader of the collection since his teenage years. A few weeks later, we meet in his office. To mark the occasion, he has brought along his complete set of 30/40 volumes. “I remember very clearly buying the Vaughn Bodē issue in 1980 or 1981 at a bookstore in Bordeaux when I was sixteen years old,” he says. “Back then, you could still find 30/40 issues tucked away in the back of shops, where they had been sitting on the shelves for years – often discounted because they were so difficult to sell.” Since then, Gabilliet has invested considerable time, effort, and more than a few francs and euros in assembling a full 30/40 collection. He has also written scholarly analyses of the series, focusing in particular on the Bodē volume.

What was the impact of the 30/40 collection on the French comics scene?

Honestly, when they first came out, they didn’t make much of an impact, except for the Tardi book, which was reprinted a couple of times. All the other issues had only one printing, with a print run of between 1,000 and 2,000 copies, depending on the title. Throughout the 1980s, the 30/40 books were published irregularly by Futuropolis, and none became a big seller – not even the ones featuring major artists like Robert Crumb, Willem, or the volume with Forest and Cabanes, who were quite popular in France at the time. However, by the late 1990s and early 2000s, the 30/40 books began to take on a legendary status – an aura of an avant-garde collection. Initially, they mainly attracted hardcore comics connoisseurs, but over time, their significance grew.

Gabilliet continues to explain that what made the 30/40 collection groundbreaking was its focus on the artist, helping to shift the spotlight from the work to the creator: it was not Blueberry that mattered, but Moebius. Through its bold, self-assured format, 30/40 made it clear that this was an art form – and an artistry – to be taken seriously. This was no small matter. In his influential study on the maturation and autonomy of the French comics field during the 1970s, sociologist Luc Boltanski highlights that the emphasis on the auteur was one noticeable factor in comics gradually gaining recognition as a legitimate literary and artistic medium – one where artistic work is increasingly understood within its own symbolic economy.

Alongside other key ingredients in the legitimization of comics – such as festivals and exhibitions, journals and specialized comic bookshops, and the publication of academic and art books – individual cartoonists, both past and present, began to be highlighted as particularly significant. The medium had acquired its own canonized artists. A cartoonist was no longer necessarily an anonymous draughtsman; certain individuals were now elevated as artists worthy of recognition in their own right, much like celebrated painters, novelists, or musicians. It is difficult to imagine a clearer expression of this than an oversized book devoted entirely to the work of a single cartoonist, their name emblazoned in large letters across the cover. Even if, due to their size and soft covers, these volumes were nearly impossible to fit on a bookshelf.

Cestac illustrates the frustration many felt when trying to fit a 30/40 volume on their bookshelf.

“That was the whole point,” Gabilliet explains. “Robial’s goal was never to make money, but to be an avant-garde activist. He came up with a format that went against all the principles of mainstream albums – those neat, sturdy books you could easily hold in your hands. Instead, he created this big, floppy thing, stapled together, in a size that made it impossible to fit on a normal bookshelf. It couldn’t even stand upright because of its flimsiness. I think Robial was particularly proud of that – anything to irritate the mainstream readers of classic Franco-Belgian comics,” he laughs. “And if that wasn’t enough, the price was double that of a Tintin album!”

What was your reaction to the news that Robial and Menu are bringing back the 30/40 collection?

I’m very happy about it. Robial and Menu are quite similar in many ways –both are iconoclastic creators – and I’ve always been aware of Menu’s fascination with the old Futuropolis catalogue. I belong to a generation that has immense respect for what Robial has done for comics since the 1970s. So I wasn’t surprised that it would be Menu who breathed new life into 30/40. He’s the obvious spiritual heir to Robial. I can’t think of anyone more worthy of carrying the torch of the 30/40 collection than Jean-Christophe Menu.

Faithful to tradition

The reader opening the latest 30/40 can be assured that Menu treats the collection’s legacy with sensitivity – while also blending it with renewal. Faithful to the tradition, his 30/40 retains the austere design with only the artist’s surname visible on the cover (the only difference being that Menu has chosen a white background instead of black). Inside, it remains a mixture of works from the artist’s catalogue, aiming to showcase both range and depth. This includes a revisiting of some of his earlier creations, such as Meder – a story about an escapee from a mental institution rendered as an entertaining orgy of senseless violence in a jagged, punk-inflected style—and his fantasy-inspired Mont Vérité universe, populated by green, rabbit-like monks and frequently laced with meta-references, often to himself and to the world of comics. Everything is, of course, printed in black and white – with the exception of the Mont Vérité story, a clear nod to Joost Swarte’s 30/40, which broke with convention by being in color. But the centerpiece of Menu’s book is two stories dealing with the deaths of his parents.

Menu’s 30/40 maintains the austere design of the 30/40 collection.

“I decided very quickly that I wanted it to be a kind of potpourri of all my different ‘axes’ – like the Méta-Mune I did at L’Apocalypse in 2014 – mixing autobiographical material, music-themed pages, my Mont-Vérité monk universe, gags, experiments, and the return of older characters like Lapot and even Meder”, Menu explains. “There would be some longer stories for about six pages, one-pagers, and strip-like sequences laid out in a more calligraphic, newspaper-inspired form. I started with a one-page Mont-Vérité gag where my monks confront two canonical figures: a Hergé character, Rastapopoulos, and a Tardi one, Otto Lindenberg. So the legacy, the line of influences, and the homages to comics were there right from the start – echoing the intimidating feeling of contributing to something as prestigious as 30/40. Of course, working on such large pages was also a real constraint for me, since I usually draw very small. It meant doubling or even tripling the number of panels per page – so instead of thirty pages, it was as if I’d drawn seventy-five. The pages were done at actual print size.

Then my father died. So making an autobiographical story about another subject suddenly felt futile – even impossible. I had to make a story about my father. That was in 2021. Then my mother died in 2023. I knew I’d have to create another six-page story about her. I wanted the two pieces to be very different, to reflect their very different personalities. They’d been divorced for decades and were like day and night. These two pieces became the spine of 30/40 – something completely unplanned when I started.”

In the story about Menu’s father, the reader encounters a cheerful, life-loving engineer who occasionally stops by L’Association’s offices in Paris to take his son out for lunch. A few bottles of wine later, both father and son are comfortably wrapped in alcohol’s warm embrace. Beyond suggesting that the apple didn’t fall far from the tree when it comes to drinking habits, the main function of these memories is to contrast them with the fragments of the same person the father becomes once dementia takes hold. Gradually, he loses his memory until, in the end, he no longer recognizes even his only son. It is moving and beautiful without ever slipping into sentimentality.

Menu observes a change in his father’s personality, contrasting the joyful person he once was with the gruff man he has become.

To portray his mother – the not entirely unknown Egyptologist Bernadette Menu – the son employs a completely different technique. Across large, meticulously detailed, realistically drawn images of the rooms and furnishings of her house – the bourgeois living room, the library with its overflowing bookshelves, the cluttered writing desk –Menu recounts key events in his mother’s life. The rooms are emptied of life, yet filled with memories. Inserted throughout these pages are naively drawn vignettes in which Menu jumps through time, recalling specific moments shared with his mother, interwoven with depictions of her final days. Even though she is barely visible on the page, she appears vividly present – a person of flesh and blood. Taken together, the stories about his parents rank among the best work Menu has produced since Livret de phamille (L’Association) – the 1995 book centered on his relationship with his then-wife and child, and a seminal work in the field of autobiographical comics.

What reactions have you received to those stories?

I received a lot of feedback on the pages about my parents. I guess it’s still not very common to talk about death in comics. At times, I felt I had managed to bring a new approach to a difficult subject – much like with the birth of my children thirty years earlier in Livret de phamille. It gave me the sense that I wasn’t entirely finished as a cartoonist – which is a good feeling.

Do you think the collection adds to your recognition as a cartoonist?

I don’t know. I’m not even sure what recognition means. I think I have a true and hardcore readership – but a very small one, maybe a few hundred people? Still, I can feel them, their vibes, their understanding of my weirdness – and I prefer that to having a larger audience that would probably misunderstand me. Proof of that: my Dargaud book was an economic disaster! I’ve sold more copies of 30/40 than of Couacs au Mont-Vérité (Dargaud, 2021). I suppose that for a cartoonist like me, a big publisher can’t really do better than a small one – or than myself.

I know I’m not easy to read. When I make a private joke referring to another strip from twenty or thirty-five years ago, I’m demanding a lot from my readers… But I make comics first and foremost for myself – just like when I was a kid. As a teenager and young adult I sometimes tried to be milder, to think about the reader’s mind, but the result was always crap. So it’s better to do my own thing and be followed by a few. That’s perfect. Bestsellers are for assholes!

Was this a one-off, or are you planning future issues?

The idea was really to relaunch the collection – to bring back its prestigious, almost encyclopaedic spirit – so yes, I hope there will be more to come. I say hope because publishing on a larger scale is getting harder and harder. L’Apocalypse barely manages to release two or three books a year. It’s a struggle for most small indie comics publishers here in France.

Who’s next in line?

I do have a few in mind, but I’ll keep that secret, since Étienne Robial is still directing the collection. He’s the boss – the one who decides! And it’s thanks to him that 30/40 exists again. It’s his thing; it’s not one of those ‘grave robberies’ we regularly see in French comics – like the current Futuropolis, or that Charlotte crapcake that pretends to be the new Charlie Mensuel but has zero legitimacy or talent to do so. I heard it’s over? Good riddance!

What role can the 30/40 series play today? The format was considered radical in the 1970s, but since then there have been numerous examples of cartoonists working in oversized formats – notably Raw, Chris Ware, and Sammy Harkham with Kramers Ergot.

I think it’s still relevant. It remains rare for cartoonists to be offered extra-large formats. I remember doing some work for Sortez la Chienne, a 90s oversized zine, but not much – so it was a completely new experience for me to create thirty large pages like that.

The post French comics history in A3: Jean-Christophe Menu and the return of the 30/40-collection appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment