On the cover of her latest book, The Ephemerata, Carol Tyler looks utterly adrift. Pale and gaunt, with disheveled hair and red-rimmed eyes, she stares intently at a strange rectangular object hovering mysteriously over a flowerpot cradled carefully in her hands. Defying Euclidean geometry, it appears to have three cylindrical prongs at one end, but only two at the other, an unsettling optical illusion that creates a disconnect between visual perception and conscious awareness, almost literally splitting the brain in two.

This unfathomable form, known as the "Impossible Trident" (or, more colloquially, a Blivet or Poiuyt), has been a staple of psychology and neurology textbooks since the 1960s, offering an object lesson in how competing parts of the human brain try to make sense of our environment. As such, it forms a perfect visual analogy for this profoundly moving, visually inventive, and dryly witty meditation on how we go on functioning when faced with the unthinkable.

The book was inspired by an especially bleak period in Tyler’s life, during which both her parents, her sister, various friends and acquaintances, and even her beloved dog died in quick succession. To make matters worse, her marriage (to underground comix legend Justin Green) was slowly recovering from a rocky patch, and she’d become temporarily estranged from her daughter, whom she’d recently had to rescue from being blackmailed by a local drug dealer. As if all this wasn’t enough, she was plagued by insomnia, chronic tinnitus, and the onset of the menopause, all while working hell for leather on a three-volume book about her father’s PTSD (eventually collected as Soldier’s Heart in 2015). The unrelenting pressure resulted in a moment of acute mental crisis during which, as she puts it, “the side of my head sheared off like an iceberg.” In other words, her brain split in two.

Like C.S. Lewis, who wrote his classic study A Grief Observed (1961) as a way of coping with the “mad midnight moment” that consumed him after his wife’s death, Tyler turned to art to help her make sense of what she was experiencing. While the subtitle, Shaping the Exquisite Nature of Grief, might make it sound like a self-help manual for the newly bereaved, The Ephemerata is anything but. Wrenched from the depths of melancholy, this is a deeply personal account of one woman’s journey through grief, absence, and loss that, like Lewis’s book, offers no easy answers. Throughout, Tyler reflects on the impact that such intense emotional pain can have on the human mind and body, and questions whether a return to normality is even possible in its aftermath.

Indeed, things are rarely simple in Tyler’s work. While Soldier’s Heart was primarily a book about her father’s traumatic experiences in WWII, that narrative thread was entwined with, and complicated by, her troubled relationship with Green and her daughter’s problems with OCD. It was also a hugely ambitious feat of comics-making, colored with a painterly eye and crammed with subtle, visually inventive details that made it a career high point for an artist who first made her name in the pages of Weirdo back in the late ‘80s. In some ways, The Ephemerata is a sequel to that book, featuring many of the same characters, continuing some of its plot strands, and embracing an equally ambitious approach to storytelling. But it’s colored by a very different mood.

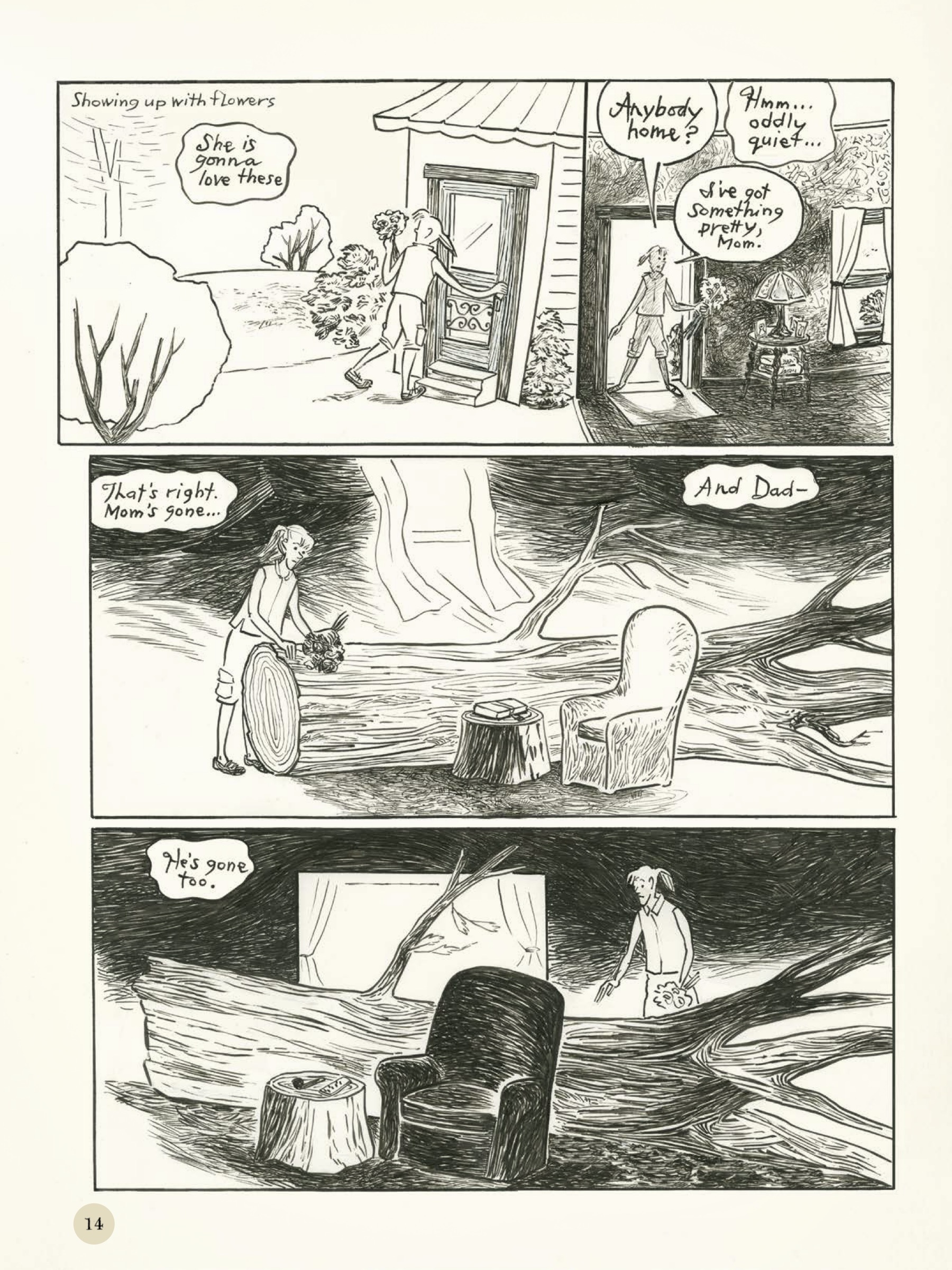

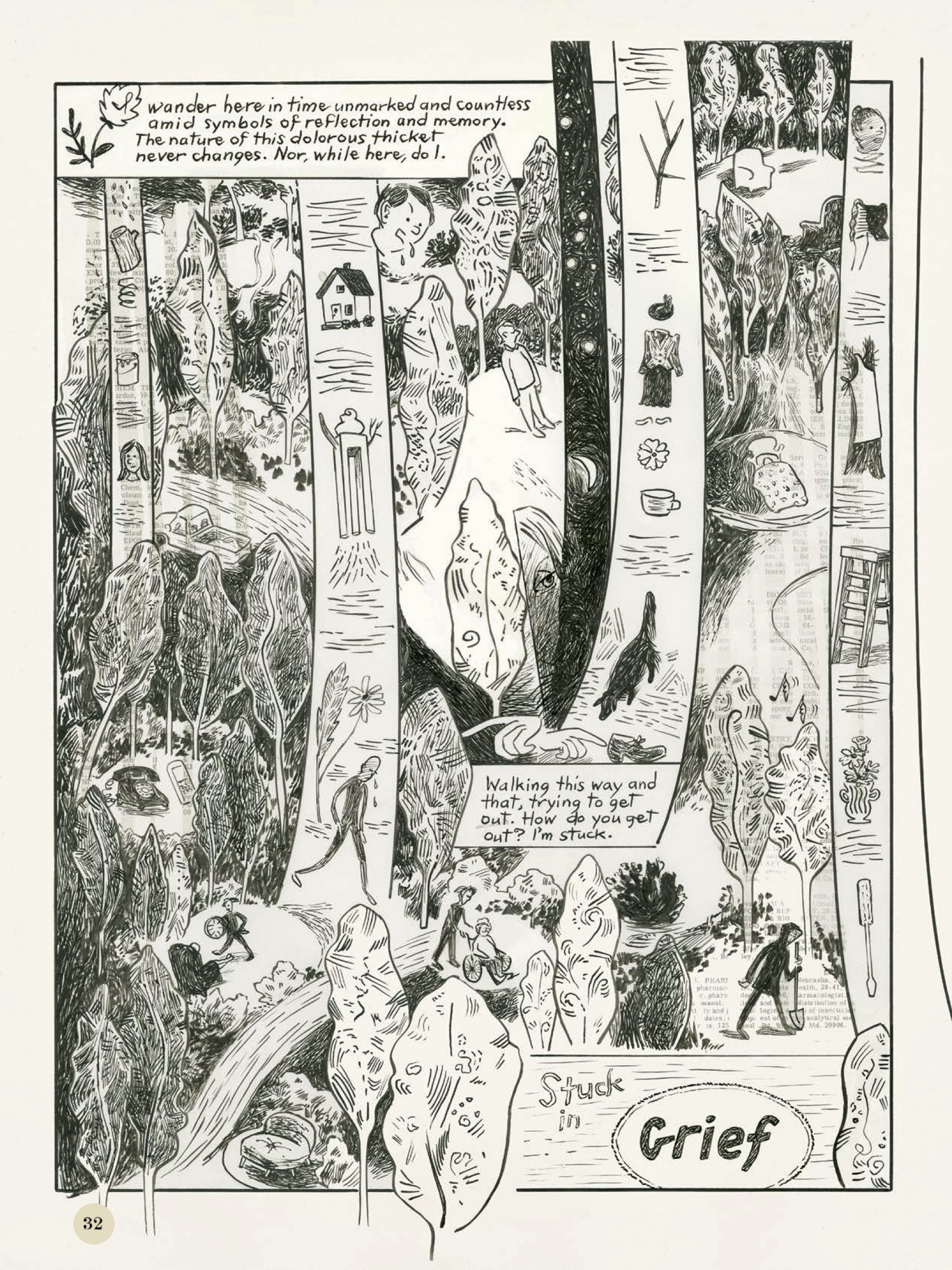

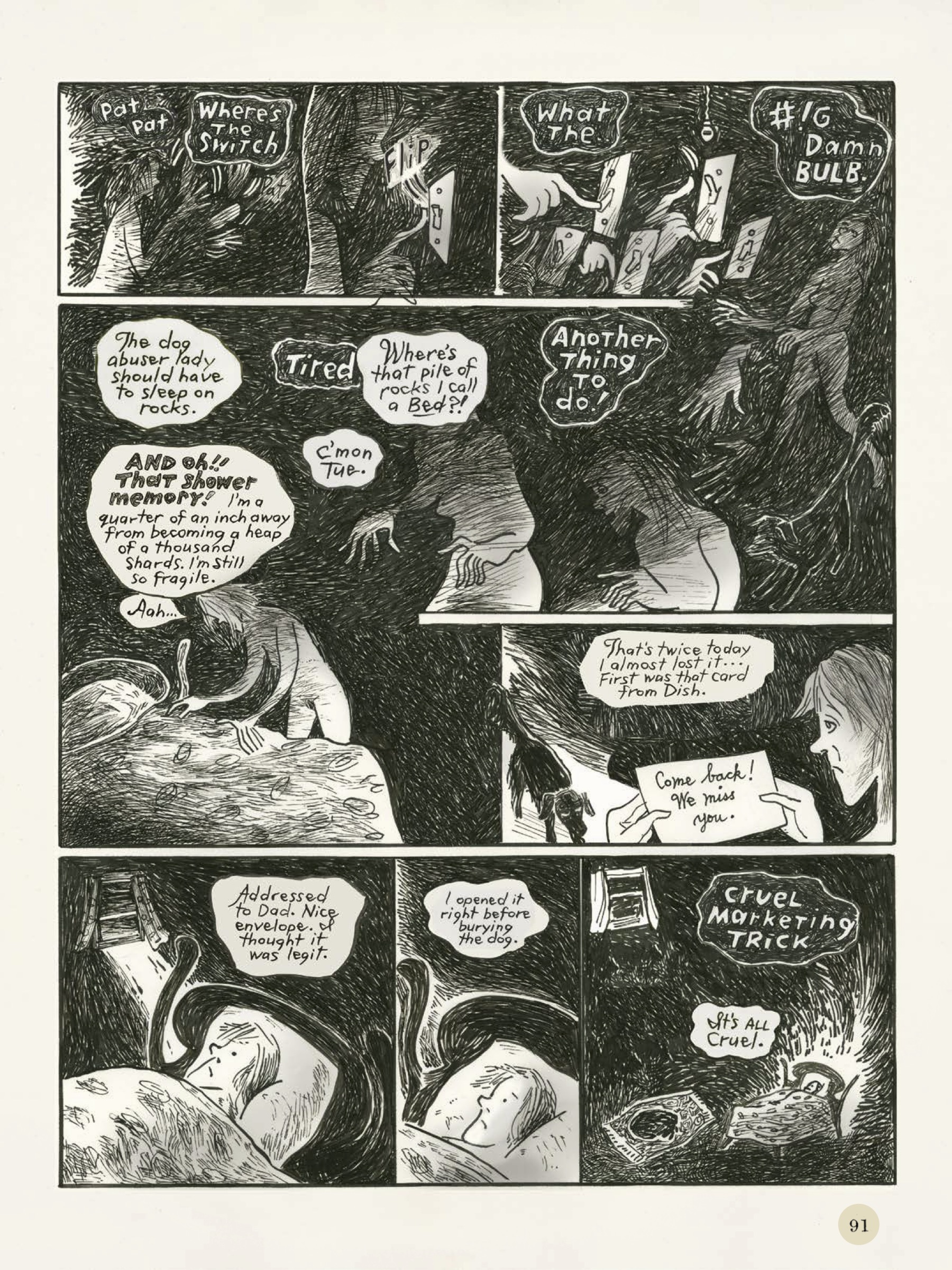

Never the most prolific of cartoonists, Tyler has been working on this book intermittently since 2011 (“in between funerals,” as she wryly notes), and the fragmented nature of its creation is apparent in the end product. Where Soldier’s Heart was ordered and neat, like a well-tended military cemetery, The Ephemerata is wild and tangled like an ancient, overgrown graveyard, and weighted by a personal symbology so dense it would need a thesis to unravel. While this can make it a challenging read in places, it also infuses its pages with a rawness and urgency that feel absolutely right given the subject matter and allows Tyler to express the torrent of conflicting emotions that engulfed her in bereavement’s wake.

Although certain pages adhere to a traditional grid structure, others are completely untethered, with images flowing into or weaving around each other, often swamped by text, overflowing with symbols, or swathed in darkly etched shadows that encroach from every angle at once. Some sequences have the loose spontaneity of a sketchbook, while others are rendered in exquisite detail. A two-page spread depicting Tyler’s family home, with its flattened perspective and flowing curlicues, recalls the elegantly designed book jackets of Edward Bawden. But elsewhere, an entire page filled with broken lines plummeting into a pitch-black void, each representing a life cut short, feels like the visual equivalent of pressing on an exposed nerve.

Despite being a sublimely gifted colorist, Tyler made the deliberate choice to work almost entirely in black and white on this project, using only occasional flashes of muted green, pink, or orange to underscore certain poignant details. But, again, this seems like a logical decision, reinforcing the book’s central theme — the inescapable duality of life and death — and echoing the long-established conventions of mourning itself.

Split into three parts, the first offers an introduction to “Griefville”, an imaginary realm Tyler created to help give form to her despair. Like Virgil guiding Dante through Hell (or maybe Purgatory), she takes us on a tour of its principal landmarks and introduces us to its curious inhabitants — Clorins, Bitterplanks, Bovinians, and others — each of whom nurtures, aggravates, or alleviates the grieving process in different ways. Before long, she’s taken up residence in an oversized mourning bonnet lined with her mother’s old clothes, while variations of the Impossible Trident float around outside like airborne jellyfish. It’s a curious start to the book, at once unsettling, oddly whimsical, and slightly alienating, leaving the reader adrift in a world they can’t fully comprehend, however carefully it’s described. But that’s probably the point. Grief is a universal experience, but it’s also something each of us has to maneuver through in our own way, and every one of those journeys is going to be different.

In parts two and three, we’re on more solid ground, back in the familiar autobiographical territory of earlier collections like The Job Thing (1993) and Late Bloomer (2005). Here, the deaths of her loved ones are recounted in heartrending detail, alongside a detailed account of the many problems plaguing her at the time (some of which were touched upon in John Kinhart’s excellent 2023 documentary about Tyler and Green, Married to Comics). From her daughter’s departure and her husband living in a separate part of the house, to sleepless nights, loss of libido, and creative impasse, the steady accretion of woes could almost become unbearable. But Tyler has always been a subtle and amusing writer, and deftly balances the pathos with moments of dry humor, tenderness, and spiritual fortitude, ensuring that the story never devolves into a simple study in human misery.

If there’s a central metaphor uniting the book, it would have to be nature. Trees, flowers, and gardens seem to sprout from every page, and Tyler explores their symbolic resonances in every conceivable way. Whether lush and verdant, withered and ailing, tangled and overgrown, or covered in needles, impossible to touch, they not only form links to the people she’s lost, but evoke the entire cycle of life, love, death, resilience, and renewal. Even a long-dead tree stump still has deep roots and growth rings that link it to history and past generations. And, as the book concludes in a long-suppressed howl of pain and anguish, she leads us to understand that grief, much like a garden, needs careful tending. If you ignore it, it will just keep growing, and eventually overtake everything.

But this is not a depressing book by any means. Confounding? Yes. Frustrating? Sometimes. But it’s also a rigorous and delightfully idiosyncratic examination of how we face loss, enlivened by Tyler’s unique approach to the medium. In her introduction, she speaks of the cathartic nature of the creative process, noting that, despite the oppressive weight of the events consuming her, she could always find a degree of respite by conjuring something meaningful out of chaos: “The exquisite beauty and delight of the art [drew] me back to the pages, the story, the fun of making it.” The saddest part is that this isn’t the end. Although originally planned as a single volume, Green’s death from colon cancer in 2022 means that a sequel is now forthcoming. And yet, despite her grim visage on the cover, Tyler never leaves us without hope. Even the Impossible Trident appears to be sprouting a sprig of new growth, suggesting that, in some curious way, it helped her put her head back together.

The post The Ephemerata: Shaping the Exquisite Nature of Grief appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment