Prolific and innovative creator Keith Ian Giffen broke the news of his own demise on social media the only way he could have - with the same dark, edgy humor that defined his nearly 50-year career in comics:

I told them I was sick...

Anything not to go to New York Comic Con

Thanx

Keith Giffen 1952-2023

Bwah ha ha ha ha

As fans and colleagues began to speculate about the cryptic post, his family confirmed that Giffen, who had written the post in advance, had passed away on Monday, October 9, 2023, aged 70, after suffering a major stroke the previous day. The native New Yorker had moved to Tampa, Florida following the death of his wife Anna, to live with his daughter Melinda and her family.

Giffen was born and raised in Queens, New York, on a steady diet of science fiction and comic books, including the stories of DC’s Legion of Super-Heroes and the Marvel comics of Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko. Like many of his contemporaries, Giffen was eager to take everything he’d learned from his Silver Age heroes and bring his own stories to the fabled House of Ideas that had inspired him during those formative years.

His first comics work was a title page illustration for a short story called “The Sword in the Star!” written by Bill Mantlo & Edward S. Barkan in the pages of the black & white magazine Marvel Preview #4, dated January 1976. Giffen soon graduated to illustrating full stories, and just a few short months later he and Mantlo had co-created the intergalactic adventurer Rocket Raccoon in the pages of Marvel Preview #7, the first of many Giffen co-creations who, eventually, would grow from cult favorite characters to global icons.

Eagle-eyed fans, however, saw something special in Giffen’s work from the very beginning of his career. “I've been a fan since his first published story in Marvel Preview which blew me away at the time with its bold, absorbing vision and storytelling vigor,” says writer Grant Morrison. “He was in his early 20s and in Kirby mode then, but he'd found a way to revitalize his influences that connected with others of his generation.”

Artist Colleen Doran was also enamored of Giffen’s early efforts, which included a yearlong stint on Marvel’s offbeat “non-team” superhero title The Defenders, where he was paired with inkers such as Klaus Janson, then a rising star, and Mike Royer, who was Jack Kirby’s primary artistic collaborator during the 1970s. “Keith’s style changed so much over the years it’s hard to recognize his early art as coming from the same person as his later art,” Doran observes. “The Defenders art doesn’t look like his later stuff at all, and you can see Keith morph as he emphasizes storytelling over flourish.”

From this very early point in his career, Giffen established himself as a gifted storyteller, and fast enough to illustrate multiple titles in any given month, freelancing for both Marvel and DC in the mid '70s. Apart from his 13-issue run on The Defenders (#42-54), most of Giffen’s work at that time consisted of short runs and single-issue fill-ins, since editors knew they could rely on him to bring any book in ahead of schedule.

In 1982, Giffen would land his breakthrough assignment at DC Comics, becoming the regular penciler on The Legion of Super-Heroes, written by Paul Levitz. DC’s most popular title at the time was The New Teen Titans by Marv Wolfman & George Pérez, and Legion, with a similar balance of teenage angst, romance, superhero action and appealing characters, developed a fanbase diehard enough to become DC’s second-best seller. Giffen’s Pérez-influenced drawing style, under the brush of inker Larry Mahlstedt, made him one of the most popular DC artists of the early ‘80s.

Buzz surrounding the Levitz-Giffen run built quickly, and less than a year into their collaboration they launched a multi-part storyline called "The Great Darkness Saga," an epic adventure that featured nearly every member of the Legion fighting against forces of evil directed by a shadowy figure, ultimately revealed as Darkseid, the seemingly immortal villain from Jack Kirby’s "Fourth World" cosmology. "The Great Darkness Saga" made the Legion one of the most talked-about books in fandom, elevated Darkseid to elite villain status in the shared DC Universe, and raised the profiles of the core creative team.

“I loved 'The Great Darkness Saga,'” says Colleen Doran. “People don’t realize what a big thing stories like 'The Great Darkness' were back then. Story arcs that went on for multiple issues, that was a huge deal in superhero comics. I enjoy those stories even now; when I sit down with my big omnibus volumes, they still feel fresh.”

Doran’s love of the Levitz-Giffen Legion led to her discovery of the Legion community, including fan-produced amateur press publications known as apazines. “I started submitting art and stories. I wasn’t very active, but everyone was super nice, and I made lifelong friendships there. Way before the internet, this is how a lot of hardcore fans socialized. The apazine was distributed to the pros as well. Keith saw my work and thought I had potential, so he called me up and asked if I’d like to audition to work on the Legion. My mom answered the phone and told Keith I wasn’t home from school yet. Keith kind of wigged out because he didn’t know I was a kid! It was pretty funny.”

Grant Morrison was equally enthralled by the early '80s Legion of Super-Heroes stories. “I loved [Keith] on Legion with Paul Levitz, and it was that book that reignited my own interest in American comics after several years.”

Paul Levitz looks back on that era with fondness, too. He admits that although Giffen was not his first choice as artist on that classic storyline, the work speaks for itself, and he’s proud of what they accomplished together. “I think ['The Great Darkness'] would have happened [whether Keith was the series artist or not]; I loved Jack's 'Fourth World' as much as Keith did. But it would have been very different, as all collaborations change work, and I don't know that it would have been as memorable. We just came together beautifully.”

During that run on Legion of Super-Heroes, Giffen continued to pencil fill-in issues for other DC titles, but the ambitious artist wanted to write—or at least plot—his own stories, and to bring his own original characters into the DC Universe. During his brief tenure on the interstellar super-team book Omega Men, he and writer Roger Slifer introduced a bounty hunter named Lobo, an assassin prone to acts of extreme violence.

Six months prior, in issue #52 of the Superman team-up title DC Comics Presents, Giffen introduced another larger-than-life character: a supervillain with the improbable name of Ambush Bug, which Giffen created and brought to writer Paul Kupperberg. Fan reaction to the sarcastic, wise-cracking chaos engine was favorable, and Ambush Bug would soon return to the pages of DC Comics Presents in stories plotted by Giffen and scripted by other writers, including Paul Levitz and Robert Loren Fleming.

With Ambush Bug, Giffen found his voice. His style loosened up considerably as his fourth-wall-breaking protagonist, fully aware that he was a comic book character, set out to make mischief, offer pointed commentary on the modern comic book industry, and to have as much fun as possible along the way. This breakthrough—the realization that superhero stories should be fun—would set the tone for much of Giffen’s subsequent work. “Keith and I shared a sensibility about comics,” observes cartoonist Ty Templeton. “We both believed our job was to make something fun. He didn't mind drama, he didn't mind action, but he focused on fun, which is the unalloyed point of a comic book in the first place.

“Ambush Bug was distilled fun. Fun with the other stuff pared away. There really wasn't a story to any of them, no matter what the plot might be. There was absolutely no character building, and no subtext to any of it... only a structure to drape a lot of silliness on top of. Who could ask for more?”

Giffen was a restless artist, sometimes changing his style to reflect commercial trends, sometimes just for his own amusement, and sometimes to emulate one of his current favorite artists. He began his career with a style that owed much to the dynamic art of Jack Kirby, then shifted toward the more detail-oriented artwork of his contemporaries like George Pérez and Jim Starlin, as reader tastes shifted in that direction.

In the mid '80s, after his departure from the Legion of Super-Heroes monthly, Giffen’s style underwent another radical transformation as his artwork became starker and more angular, with heavily-inked panels and bolder, more dramatic page layouts and compositions - unleashed in, among other titles, DC Comics Presents and other venues for Ambush Bug, including an eponymous 1985 miniseries. Fan reaction to Giffen’s new style was decidedly mixed, with some Legion fans on board with the artist’s reinvention, and others preferring Giffen’s more traditional superhero illustrations.

But in the February 1986 issue of The Comics Journal (#105), writer Mark Burbey published an article revealing that Giffen’s transformation owed much, or perhaps everything, to the work of Argentine comic book artist José Muñoz, known throughout Europe as the creator, with writer Carlos Sampayo, of the popular detective series Alack Sinner. Burbey’s article alleged that Giffen’s new look was no homage to Muñoz, but little more than a carbon copy of his work. “I counted a minimum of 70 swipes spread out among eight comics, with 28 swipes in Ambush [Bug] #1 alone,” Burbey noted, concluding the article with a detailed breakdown of pages and panels, and their relationship to the same from Alack Sinner.

Several issues later, in The Comics Journal #118, Giffen admitted that he had so thoroughly immersed himself in the study of Muñoz’s artwork that he had "ceased to be Keith Giffen," but denied that he had traced any of Muñoz’s comics directly, or even worked with those comics in front of him. In the same issue, Muñoz countered that he recognized members of his own family who had posed for him in Giffen's comics. "That's not the way I recommend treating other people," Muñoz remarked.

"I love those Muñoz-inspired years,” says author/illustrator Jed Alexander. “I personally think, not being the draftsman Muñoz was, [Giffen] took Muñoz's style and codified it into a more cartoon and design-oriented language. There were some direct swipes, no question, but he took superficial elements of Muñoz’s style and used them to develop a spare, bare bones vocabulary of symbols; amorphous shapes to suggest atmosphere; everybody had a face that looked like Alack Sinner at his most abstract. Often this was squeezed into Giffen's trademark nine-panel grid. In the end, it wasn't as though you could in any way mistake Giffen of this period for Muñoz, but the stylistic influence was still very apparent.”

For a while, Giffen shifted his focus from penciling comics to plotting and providing layouts for other artists. By the time DC had concluded its line-wide reboot Crisis on Infinite Earths, a massive crossover event that affected every DC title published in 1985 and 1986, Giffen had firmly established himself as talented, popular creator with a wicked sense of humor and the ability to handle large, eclectic casts of characters. While he may not have been the most likely candidate to take charge of DC’s iconic superhero team the Justice League of America, he wasn’t shy about contacting editor Andy Helfer, who’d been tasked by Editor-in-Chief Dick Giordano with relaunching the series and making it relevant to modern audiences, and letting Helfer know that he was the right man for the job.

Although the updated Justice League title was initially planned as a showcase for DC’s most famous superheroes, just as it had been in 1960, Helfer was informed that due to the recent Crisis-instigated reboot, many key DC characters—including Superman, Wonder Woman, Flash and the Silver Age Green Lantern—would be off-limits for the team roster, as those characters were still being reestablished in their own solo titles. Undaunted, Giffen accepted the challenge of writing a new Justice League, whose roster would be determined by the events of yet another crossover event, Legends, where a group consisting of Batman, Captain Marvel and several lesser-known characters would come together to battle the forces of evil, and ultimately form a new Justice League.

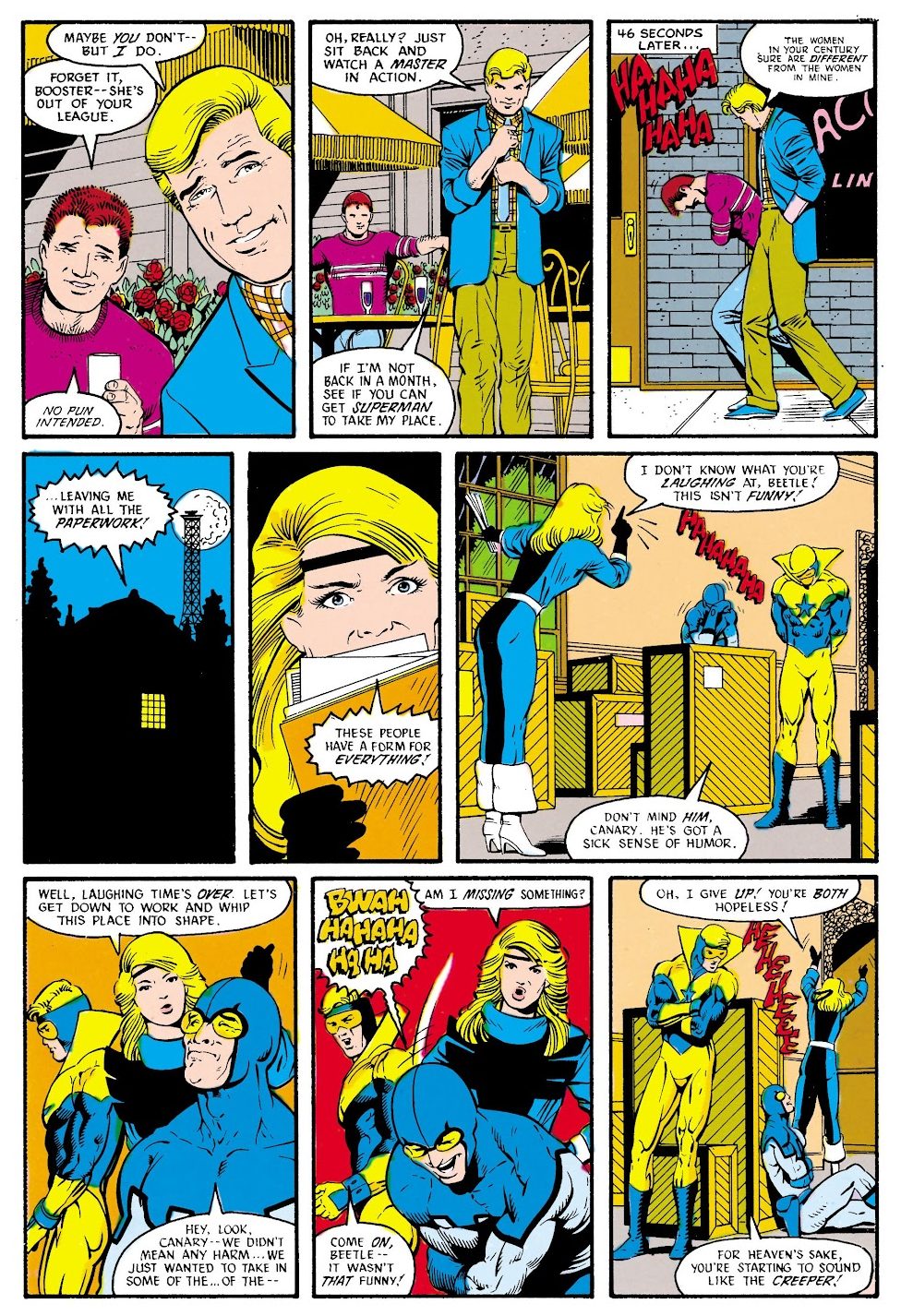

But how would Giffen get readers excited about a team book that starred second-stringers and forgotten characters like Blue Beetle, Guy Gardner, Black Canary and Dr. Fate? Helfer, in his 1989 introduction to the Justice League: A New Beginning trade paperback, explained that he and Giffen decided on a high-concept approach that would bring a whole new perspective to the DC Universe, and to superhero teams as well. “What if we didn’t create a story per se -- but instead focused on the environment that our characters would inhabit? The Justice League was, in fact, a ‘club’ for super-heroes… why not focus on that aspect? Instead of working up a world-threatening menace for the group to fight in the first issue, why not linger on the simple interrelationships of heroes?” Helfer mused. “From these discussions between Keith and myself a philosophy was formed.... The Justice League is a fraternity where heroes can take their masks off and let their hair down. They can be human for a change -- and, in effect, be like us.”

Giffen also wanted to drop the “of America” from the team's traditional title, and suggested the rebrand begin as simply Justice League, with the title becoming Justice League International in the aftermath of the new team's first full story arc. “The proliferation of nuclear weapons, the impending greenhouse effect, world poverty, devastating diseases… all have made the world much smaller,” noted Helfer in 1989. The in-story explanation for the change of name and mission for the Justice League was due to the machinations of businessman and entrepreneur Maxwell Lord, an ‘80s Wall Street tycoon who felt that the world’s superhero community could be far more effective with a person like him calling the shots.

Joining Giffen, who felt that character dialogue was not his strong suit, was writer J. M. DeMatteis, who had recently teamed with him on a Dr. Fate miniseries. “Although it came out after Justice League launched,” DeMatteis recalls, “my memory is that we began working on [Dr. Fate] before Andy Helfer put us together for Justice League. Fate was one of the few times we worked as a traditional writer-artist team, and I fell in love with Keith’s art right away. And, of course, his incredible storytelling skills. He was always adding wonderful little touches to the story.”

At the time, DeMatteis was best known for thoughtful, spiritual comics, including Moonshadow for Marvel's Epic Comics line and the Marvel Graphic Novel Greenberg the Vampire, but Helfer and Giffen knew that he had a great ear for dialogue, and were confident that he could supply both depth and humor enough to bring Giffen’s plots to life. “During our original JL run, we worked in glorious isolation,” DeMatteis says. “Keith would do the plots, Andy would send them over to me and I’d just build on what Keith had done. People think we were in a room together, like a traditional writing team, but that wasn’t the case at all. We’d see each other at the DC offices, go out to lunch with Andy, but we only spoke on the phone occasionally.

“That said, there was an instant creative chemistry, something magical that happened when our two perspectives came together.”

Penciling the book would be newcomer Kevin Maguire, an artist with a flair for facial expressions and body language, who would illustrate Justice League based on layouts—storyboards, essentially—drafted by Giffen. “Keith’s gorgeous layouts were like Harvey Kurtzman’s for EC Comics. Very cartoony, almost like Dennis the Menace, just beautiful stuff,” notes Al Gordon, who would ink Maguire’s Justice League for nearly a year, starting with the series’ second issue. “[The layouts] were basically his plot - he’d draw those, send them to Andy Helfer, who would look them over, then send them to [DeMatteis] and Kevin [Maguire], who would get to work on the scripting and the penciling.”

Scripting over Giffen’s plots was always an adventure, and one that DeMatteis welcomed throughout their long creative partnership. “There was no ego involved when Keith and I worked together,” says DeMatteis. “The basic plots, the rock-solid building blocks of our stories, were all Giffen - but I had the freedom to bend and twist those stories any way I chose. Someone else might have taken offense at the changes I’d make, but Keith always encouraged me to follow my muse, adding new plotlines and character bits via the narration and dialogue. He, in turn, would build on what I’d done, always surprising me with his extraordinary leaps of imagination. It was, as I’ve often said, like a game of tennis: We’d hit the ball back and forth, and, as we played, the stories evolved into something more than either of us could have ever achieved on our own.”

Giffen and DeMatteis, alongside Maguire and a host of other talented artists—including Adam Hughes, Ty Templeton and Linda Medley—would guide Justice League for nearly five years, establishing it as one of DC’s most popular and acclaimed monthly comic books, including a spin-off team book, Justice League Europe, several miniseries spotlighting individual members or the team entire, and several major crossover events, including the 1988 miniseries Invasion!, which Giffen scripted with his longtime friend, Bill Mantlo.

The Giffen and DeMatteis run of Justice League breathed new life into that classic superhero team, and elevated many “B-list” characters to fan-favorite status, including the now-iconic duos of Booster Gold & Blue Beetle as well as Fire & Ice. The incredibly brief fistfight between Batman and Guy Gardner in issue #5—begun and concluded with “One punch!”—is regarded as one of the most memorable hero-versus-hero battles in comic book history. And fans today still interject the series’ trademark “Bwa ha ha!” laugh into any discussion of the late ‘80s Justice League, at comic book conventions, online, or anywhere else that seems appropriate (or inappropriate).

Also in the pages of Justice League International, Giffen, DeMatteis and Maguire reinvented Giffen's co-creation Lobo as an over-the-top parody of ‘80s masculinity: a badass interstellar biker with a foul mouth and a short temper. This new incarnation of “The Main Man” struck a chord with readers; a series of guest appearances throughout the DC Universe and a stint in the Invasion! spinoff L.E.G.I.O.N. led up to the character's first solo miniseries in 1990-91, plotted by Giffen, scripted by Judge Dredd and Detective Comics writer Alan Grant, and illustrated by 2000 AD artist Simon Bisley. The miniseries was a huge hit, spawning several sequels and an ongoing series, through which Lobo became one of the characters that defined the DC Comics of the 1990s.

As Giffen’s Justice League and its spinoff titles flourished, he looked to his own past—and the distant future—reteaming with Paul Levitz to close out Levitz's run on Legion of Super-Heroes, on which he had worked through various re-numberings since the late 1970s. With Giffen penciling and co-plotting, the two would guide that series, the third 'volume' of Legion, through its final year of publication to a conclusion in 1989, at which point Levitz stepped away to focus on his duties as publisher at DC.

Since Giffen was riding a hot streak thanks to Justice League International, and had ample experience both writing and drawing Legion, the decision to turn creative control of the forthcoming fourth volume to Giffen was a foregone conclusion. “I’d been the inker on Justice League for about a year and a half, and Keith calls and says, ‘Want to work with me on a project?’” recalls Al Gordon. “Keith said, 'I talked to Paul Levitz, and when he finishes up Legion, he’s going to let me reboot it. I’m going to skip ahead five years from now, so the characters are in their early 20s.’ I told him I had to think about it, since I thought I was still inking Justice League, but it seems Keith knew I’d been taken off that book before I did. Keith then said if I needed to keep busy, I could ink him on the Legion issues he was drawing that would close out Paul’s run… I only had to think about that for about five minutes before signing on.

“Keith and I talked about Legion for six months, maybe a year, before we actually started on the first issue of the new series. We’d talk about story ideas for hours.”

Serving as editor on the series—the “Five Years Later” run of Legion of Super-Heroes that commenced in late 1989—was Mark Waid, whose approach to the series was to stand back and let Giffen take the lead, since that was going to be the end result anyway. “When I was handed the Legion franchise to edit after Paul Levitz ended his long run as writer, Keith elected to stay on as artist and plotter, and I felt like I was riding a bull at the rodeo - it was all I could do to hang on,” says Waid. “I let Keith have his head completely and totally - he was just winding down his Justice League run at the time, and he was arguably DC's most valuable freelancer, so who was I to give orders?

“Really, all I did was watch Keith (choose and) lead his collaborators—co-plotters/dialoguers Tom and Mary Bierbaum, inker Al Gordon, and colorist Tom McCraw—to create the ‘Five Years Later’ run on Legion that's still talked about to this day.

“And what I remember most about that launch is that Keith got the last laugh. Everyone on the DC staff who read the advance copy that was circulating around the offices hated it. H-A-T-E-D it. Christ, the flak I got from everyone from marketing to editorial to the art director, all of whom thought it was impenetrable, Byzantine, and incomprehensible, rather than what it really was and what Keith was so very often: way ahead of its time. Every one of those other editors was busy running point on some now-forgotten lame-ass, pedestrian title or another. Meanwhile, Keith was producing a series that set new standards in storytelling. And he just kept doing it. You never had the slightest clue what you were going to get in a Keith Giffen comic, but it was always entertaining.”

Tom and Mary Bierbaum were highly regarded as Legion experts among the fan community, and Tom’s background as a journalist made the Bierbaums Giffen’s first choice as co-plotters and scripters for the series. Giffen would plot and pencil, while inker Al Gordon would also serve as part of the Legion brain trust, contributing story ideas and serving as a sounding board for Giffen. “Most of my story ideas went to Keith, always in [phone] conversation, then he’d call Tom and Mary,” Gordon recalls. “From talking to Tom a bit later on, I figured out that sometimes Keith would tell them an idea that he actually thought I had come up with, then they’d talk, and Tom and Mary would write up the script after seeing Keith’s pencils, and whatever parts Keith told them were my story ideas, would end up completely different than anything I had actually intended. It was like a literal game of telephone. But we had a blast. A real explosion of creativity.”

“We’d talk on the phone for hours,” continues Gordon. “He made fun of that in an issue of Ambush Bug - sometimes I’d call and his wife would answer, and I’d talk to her for an hour before she passed the phone to Keith. He’d ask who she was talking to, since he assumed it was one of her friends, then she’d tell him, ‘It’s your weekly call from Al.’”

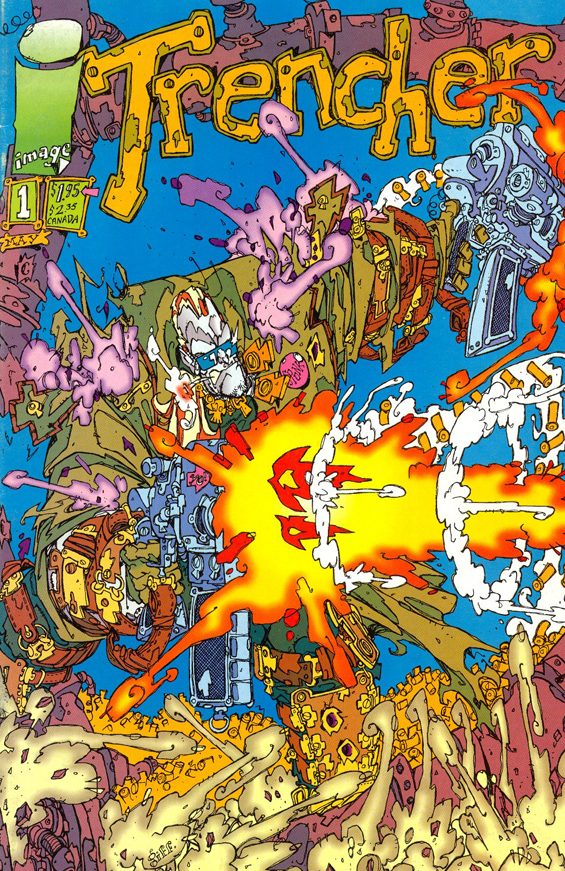

As 1993 dawned, three years into volume 4 of Legion of Super-Heroes, which had been preceded by a full year as penciler and plotter with Levitz on the preceding volume, Giffen felt it was time to move on and explore new challenges, and take yet another unexpected direction for his art and career. Newly established publisher Image Comics welcomed Giffen with open arms, and he immediately found himself plotting and doing layouts on several titles with Image founder Erik Larsen, including SuperPatriot and Freak Force, both spinning off from Larsen’s The Savage Dragon. Giffen also took the opportunity to write and draw his own creator-owned series, Trencher, a four-issue miniseries starring a belligerent, zombie-like antihero whose job is to exterminate souls that have been wrongfully reincarnated. The satirical, cartoonishly violent series was in some ways Giffen’s attempt to top Lobo, although many of the teenagers who made Trencher a surprise favorite loved it without any hint of irony.

“Keith was flexible as an artist. He could bend if it was necessary and he was pretty good at imitating others,” observes Erik Larsen. “His storytelling was solid. There was no confusion there. When he laid out pages for others, which was how he plotted early on, it was very Kurtzmanesque. He took a lot from Kirby and Kurtzman and at times emulated various other artists. Keith came up with his Trencher style as a way of drawing a book without having to pencil it. The style was cartoony enough and open enough that he could just wing it.”

Giffen drew for himself, first and foremost, and was generally immune when it came to feedback from readers, colleagues, and even publishers. And that suited him just fine. “Some of his later art was harder to read, but I think that came from how he spotted his blacks, it was quite eccentric,” notes Colleen Doran. “So it wasn’t the layouts, anyone else working from the same layouts would be easier to read. But those blacks were dramatic and startling, very powerful.

“Keith didn’t care very much about fidelity to reality, anatomy, and of that sort of thing in his own art. He admired people who did it, and he liked working with people like me who could do those flourishes and people like Kevin Maguire who did great anatomy and terrific body language. But for Keith, it was all storytelling. He was a true cartoonist.”

Following that brief tenure at Image, and a lateral move with Trencher to the short-lived Blackball Comics, Giffen took on freelance assignments at Dark Horse and Valiant, but after 20 years of nonstop work in comics, he felt it was time to step away to find new artistic avenues. He had somehow found time to work as a storyboard artist on The Real Ghostbusters television cartoon in the late 1980s, and with the comic book industry in a slump after the market collapse of the mid '90s, he returned to television as a storyboard artist on both live-action series and animation, including the Cartoon Network series Ed, Edd n Eddy.

It was during this time that Giffen met Shannon Eric Denton, who would become his writing partner for 15 years, from 1997 until 2012. Denton was working at Marvel when a movie development exec named Leo Partible approached him about working with Giffen in adapting one of Denton’s comic book concepts for other media. "That introduction led to many conversations,” recalls Denton. “That led to him asking me to work on all the Hollywood stuff with him and me learning a lot of what I know about storytelling. This led to many years of Keith and I collaborating as writing partners on various projects, me throwing him storyboard work whenever I could—because he was great at it—and him just becoming one of my closest friends. People like to joke about Keith’s curmudgeon side but if he loved you, and you were in his group, you were for life and you knew it. I benefited a lot from him craft-wise, but more importantly in my life.”

Giffen and Denton collaborated on a variety of different projects, including comic books as well as movie pitches and animation. “We did screenplays, lots of short stories in our Komikwerks books, Image Comics one-shots, OGNs, and our kids' comic ZAPT! over at Tokyopop, plus lots of storyboarding,” says Denton. “We chatted an hour a day at the beginning of every workday for a decade plus. I was the L.A. guy, so I was usually the one selling our properties for TV/film. [His wife] Anna had Keith on a no-talking policy after a few of our early meetings together because I’d be about to close a deal and then Keith would start pitching new fabulous ideas and I’d have to steer things back to the project they were in the middle of buying in the room. It was a good problem to have. We worked well together, as Keith did with all his collaborators.”

Giffen never completely left comics behind, and an intriguing project or pitch was often enough to get him back in the saddle. In 2003, more than 10 years after he and J. M. DeMatteis had concluded their tenure on Justice League International, the pair teamed with artist Kevin Maguire and inker Joe Rubinstein for the six-issue miniseries Formerly Known as the Justice League, an out-of-continuity tale that reunited several core characters from their original Justice League series along with other classic DC characters.

“It wasn’t until we came back together for Formerly Known as the Justice League that we—and I include the brilliant Kevin Maguire in that ‘we’—realized how special our collaboration was,” says DeMatteis. “From then on, Keith and I spoke regularly, discussed the stories, became friends. But even then, surprise was the key element in our work together. Even if we discussed what was coming up in a particular issue, Keith inevitably built it into something unexpected. And I was free to do the same with the scripting. Over the years we achieved a kind of mind-meld. A fusion of our two sensibilities.

“Keith and I worked on so many projects together—I was amazed the other day when I started counting them all—right up until Scooby Apocalypse just a couple of years ago. I used to say that if Keith called me up and asked if I wanted to work on Millie the Model I’d say yes. The project itself was secondary to the joy of the collaboration.”

It was during this era that Giffen made a return to Marvel Comics, which tapped him to take over their cosmic heroes line following the departure of longtime creative lead Jim Starlin. Editor Andy Schmidt, after consulting with supervising editor Tom Brevoort, hired Giffen to write the final six-issue story arc of a series starring Thanos, which would lay the groundwork for the ambitious crossover event Annihilation. “Keith and I had a different take on the characters and universe than Jim had. And that was by design,” says Schmidt. “We wanted to go a little harder sci-fi and a little more run-down and grungier - a world more lived in and that had maybe fallen on hard times. And that’s what we did with the Thanos book. It was to test the waters a bit, see if we could come up with something we liked and that audiences responded to."

“From Thanos, I was able to get a Drax the Destroyer limited series approved, and while Thanos was the proof of concept of our general ‘vibe’ of Marvel Cosmic, Drax was the proof of concept for Annihilation, the event that would recast the whole universe in a big way. I didn’t get a ton of traction [at first] as there wasn’t a lot of faith in sales for those books. The last time they had sold well was in the mid '90s, a decade earlier at the time. So it’s a tough sell. If Marvel Cosmic was becoming my sandbox from an editorial perspective, Keith was the guy I wanted building the sandcastles with me - the major structures. And because we got along so well, it worked out remarkably smoothly.”

The Giffen-written Annihilation was a critical and commercial success, laying the groundwork for the revival of Marvel’s cosmic line, and, under the auspices of editor Schmidt and writers Dan Abnett and Andy Lanning, the introduction of a new lineup for the spacefaring superhero team the Guardians of the Galaxy, consisting of Star-Lord, Gamora, Drax, Groot and Giffen co-creation Rocket Raccoon - whose personality and temperament, friends claim, were modeled on Giffen’s. And it was that incarnation of the Guardians of the Galaxy that would inspire a trilogy of major motion pictures from Marvel Studios, and would turn Rocket Raccoon, introduced in the pages of a long-forgotten black & white magazine in the mid '70s, into one of the biggest box office stars of the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Thirty years into his comics career, Giffen was busier than ever, and still in high demand from multiple publishers. Following his successful revival of Marvel’s cosmic heroes, DC Comics reached out to him with an opportunity to tackle the most ambitious project of his career.

In the aftermath of DC’s 2005-06 crossover event Infinite Crisis, all of DC’s ongoing comics would skip ahead an entire year in continuity, in a publishing initiative branded “One Year Later” - a storytelling device reminiscent of Giffen’s own five-year time jump for Legion of Super-Heroes back in 1989. The lost year of stories would be revealed in the pages of a weekly series called 52, a title written by Geoff Johns, Grant Morrison, Greg Rucka and Mark Waid, illustrated by a dozen different artists, and sporting covers by J.G. Jones and colorist Alex Sinclair. Keeping 52 on schedule would fall to Keith Giffen, who would provide layouts for the entire series: 20 pages per week, every week for a full year, as well as any additional freelance projects that he could handle. “Having Keith do full breakdowns on all 52 issues was the masterstroke that pulled the whole project together,” says Waid. “It's not just that it gave the artists a leg up and made them faster, it's that Keith's natural rhythms as a storyteller helped the work of four very different writers feel seamless. Grant, Geoff, Greg, and I all have different styles, different approaches to the page, different methods of achieving suspense and emphasis, and somehow Keith made it all work without in any way diminishing anyone's scripts. That series contained 1,040 pages, and I cannot think of a single one where anyone had any notes for Keith.”

Morrison concurs with that assessment. “When we worked on 52, Keith was always the wry voice of reason in the room, steering us clear of the pompous and pretentious with a perfectly-timed barb or three! The curmudgeonly rep belied by a blazing exuberant love of comics. He was very much our fifth Beatle on that book, certainly!”

DC retained Giffen for their subsequent yearlong, 52-issue weekly miniseries Countdown to Final Crisis. No matter how much DC changed up their continuity, no matter how many different executives passed through their offices, Giffen always managed to stay in their good graces, and was always one of the first people that editors called when it was time to create a new character, chart a new direction for a struggling title, or to direct an epic crossover. “Keith delivered. He was professional from when he returned to comics, and he always put his work first,” observes Paul Levitz. “There were periods when his creative experimentation made for—ahem—interesting results, but it was always there on the page. And he wasn't a curmudgeon in the sense of being difficult to work with. He was a nice guy who liked to seem gruff, a fast and professional deliverer, and talented. Normally you only need to be two of those three to make a living in comics.”

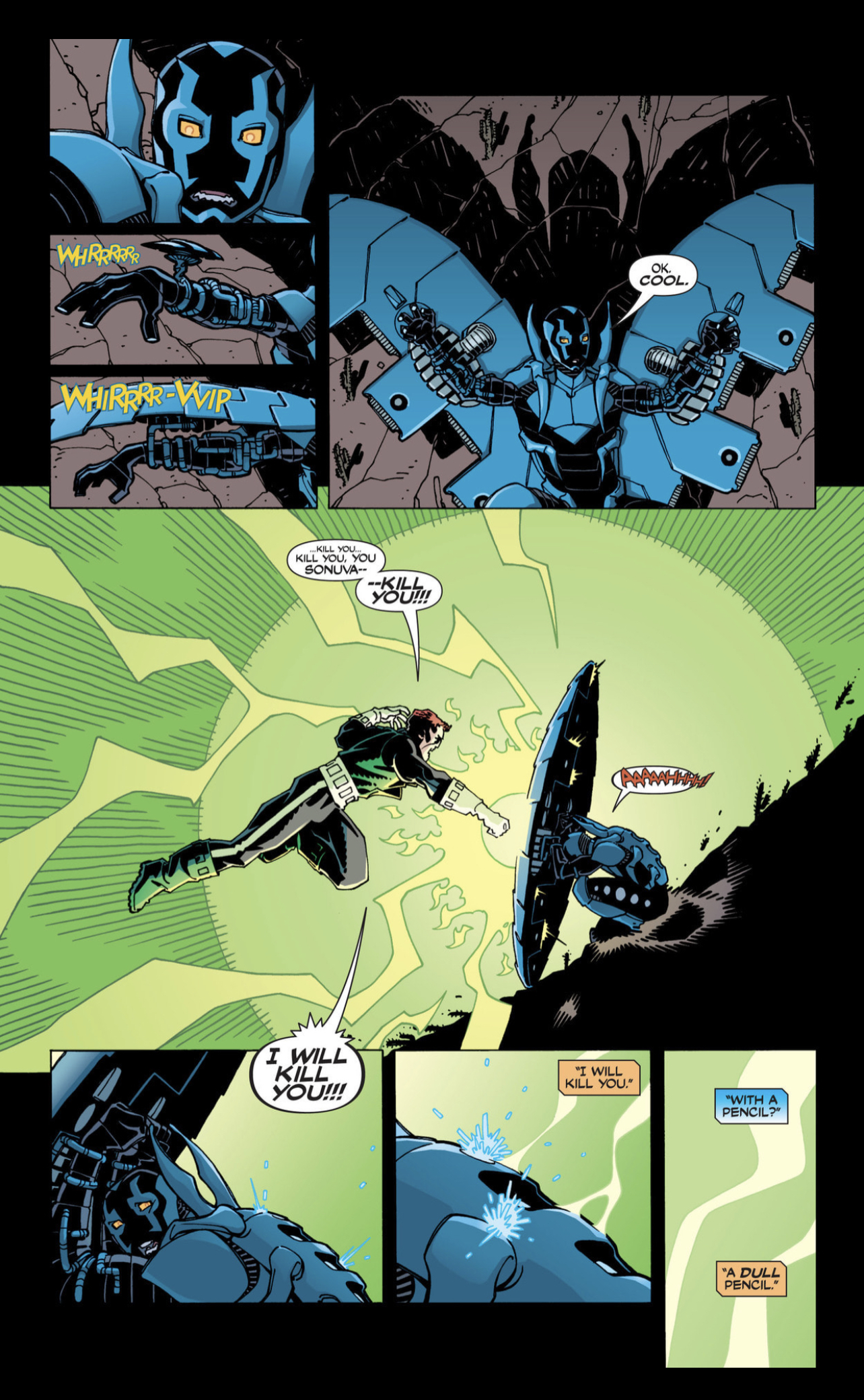

The death of the Ted Kord, the Blue Beetle who had appeared throughout Giffen’s entire run on Justice League, had kicked off the Infinite Crisis crossover event, and plans were already in motion to introduce a new, teenaged character who would carry on the name and legacy of the Blue Beetle. Giffen and screenwriter John Rogers were assigned to craft the origin and first stories featuring the new character, and would team up with artist Cully Hamner to create Jaime Reyes, the new Blue Beetle. “When I was asked to do it, Keith and John already had, as I remember, a background doc and a first-issue script,” says Hamner. “So, there were ideas in place about the characters, setting, etc. In a comic, though, you can only go so far without knowing what the characters look like because that, in turn, feeds the further development of the characters - especially when a character’s abilities come directly from what they’re wearing. DC’s art director at the time, Mark Chiarello, asked me to take a pass at it. They’d had several others give it a shot and DC had some specific guidelines, mainly that they wanted sort of a Japanese/mecha design. And I think the other artists did their best to give them what they were asking for, but after reading the material, that direction didn’t make much sense to me.

“Jaime’s Mexican culture and his family were at the forefront of what Keith and John wrote, so I gave DC a design that I thought reflected that, especially in the mask, which had a luchador influence. I also felt that a complicated robot-style design wasn’t something that anyone would want to draw on a monthly schedule, so I went for a more humanoid shape - albeit with a Beetle-ish silhouette.”

Giffen, especially at this point in his career, was never shy about sharing his opinions and would always speak up if he disagreed with an editorial decision that wasn’t in service to the story that he wanted to tell. His collaborators appreciated that he was always willing to hear them out, and that he would always have their backs. “I think Keith kind of appreciated that I didn’t give DC what they thought they wanted, proceeding instead directly from the character and their script,” says Hamner. “He and John even ran with things that I’d written in the margins of the designs. It really was a situation where we were all feeding off of each other creatively.”

Another of Giffen’s creative decisions was to expand the geography of the DC Universe beyond the traditional stomping grounds of New York, Metropolis and Gotham City. “I think DC’s original ask was that the character would be a Hispanic teenager in NYC, but Keith made him specifically Mexican-American and in El Paso,” adds Hamner. “I’m told that this was reflective of Keith’s own experience of being married to a Latina, but I that’s secondhand - not something he ever told me himself.

“Keith was great. We’d call each other here and there while I was on the book… and we’d rarely talk about the book. Mainly he would make me laugh, and I would try to make him laugh and I never seemed to be able to make that happen. Which isn’t to say I couldn’t amuse him - he just never conceded the laugh! Creatively, though, he was always an idea machine, although, at least when we worked together, he wasn’t forceful about it. He liked that I had ideas, too, that I contributed. It was a great time, and a lot of that was because of him.”

Although comic book fans are generally reluctant when it comes to legacy characters carrying on the identities of established heroes, Jaime Reyes developed an enthusiastic fan following almost immediately, from his introduction in the pages of the Infinite Crisis series to his own Blue Beetle solo series that spun off from the crossover event in 2006, written by Giffen & Rogers with art by Hamner. A few years later, the new character debuted in television animation on the team-up cartoon Batman: The Brave and the Bold. In the summer of 2023, the Jaime Reyes Blue Beetle starred in a Warner Bros. feature film, bringing yet another Giffen co-creation to the silver screen.

Several episodes of Batman: The Brave and the Bold, coincidentally, were written by J. M. DeMatteis, who welcomed the opportunity to introduce a whole new generation to the Giffen-DeMatteis “Bwa-ha-ha" Justice League. Reconnected with Giffen after the Formerly Known as the Justice League series, they made up for lost time through marathon telephone conversations as they talked about life, comics and everything under the sun. “We’d talk about politics, our families, the ups and downs of freelance life,” says DeMatteis. “Sometimes a phone call with Keith was like being part of an old-fashioned comedy team. I’d feed him straight lines and he’d go off on a hilarious 10-minute riff. One of the things I loved about working with him was that his plots gave me permission to tap into my own Inner Idiot and be as silly as I wanted to be. We were like a couple of vaudevillians, the Sunshine Boys of comics.”

Other fans-turned-collaborators-turned-friends also cherished their time with Giffen, and marveled at his nonstop creativity. Writer Gail Simone, via social media, said that Giffen was one of the most welcoming and encouraging creators that she met when she first broke into the industry, at a time when some pros were actively hostile toward newcomers. “Keith was, and always will be, a hero of mine. He did comedy so well that people might not always be aware of how his work could be SO dark, and just as brilliant.... I thought he hung the moon, still do...

“[C]ranky rep or not, he was unfailingly kind and supportive to me, even when I had the most self-doubt,” Simone continued. “We spent time together, and I was in awe of what an idea machine he was, I have never seen anything like it. During a busy, crowded lunch, he probably told me ten ideas for series, and each one was incredible. His DNA was all the stuff I love about comics, wild ideas, expansive vistas, and laughter though the tears, my favorite emotion to write. If you read my work, you will sometimes see a pale imitation of Keith's voice coming through. It's because Keith gave you courage to do something that wasn't just guns and punching.”

Colleen Doran, whose friendship with Giffen goes back to her teenage years, knew him not just through phone calls and comic book conventions—although there were no shortage of those—but through family dinners and museum outings, high tea and garden walks. “He was real, absolutely no B.S. He was one of the most wildly creative people I’ve ever met,” says Doran. “Lots of people think they’re creative. Keith shot off sparks, he always had some completely off the wall observation or idea. Most of them were never going to go anywhere, that’s not the way this business works. But I never met anyone as creative as Keith. Everyone loved him because he had no filters and you had no issues whatsoever trying to figure out what he was doing behind your back.

“We always stayed in touch, he was always there in the wings for me, always at my side. Sometimes we’d fall out of touch for awhile; when Keith was going through bad times, he’d go quiet, he didn’t like to wallow. And you’d think, ‘Hey, what’s going on, Keith’s not returning calls!’ And then you’d finally get in touch again and find out the sky had caved in on him and he didn’t want to bother you.”

Those contradictions, the curmudgeon with a heart of gold, the crass comedian who was thoughtful and introspective, those are what made Keith Keith, says Doran. ”I mean, here was the living embodiment of Rocket Raccoon, but he loved to quietly walk through museums and look at beautiful things. Of course he had more than his fair share of sarcastic comments, but I was always interested in his thoughts about art. I remember spending a long afternoon at an exhibition of Buddhist art, going quietly from scroll to scroll. And Keith had a very, very dark sense of humor, but when we got to the scrolls about Kali and so on, well, we didn’t stick around too long. That stuff gets harsh. Keith wanted to wander off and see the Fabergé.”

“Keith took in everything, he was a magpie, and he was willing to change, which a lot of artists won’t do,” Doran continues. “They stick to a look, a thing, and that’s it. And the art dies. But Keith bounced around, he had no ego that way, he was all about the storytelling. He was mostly doing layouts in later years, but he was talking about doing a new project at the end, it makes me so sad he wasn’t able to move forward with it.”

Giffen’s health had deteriorated significantly in his later years, to the point that he made a running joke with his close friends of his impending demise. “Keith had died before. I mean, literally,” adds Doran. “Had to be resuscitated. He once dropped dead on the treadmill in his doctor’s office while getting a physical. Keith dying was a running joke, because Keith made a joke about everything. We all knew Keith was in poor health and frankly, I’m surprised he lasted to 70.”

But despite the knowledge that he was living on borrowed time, or, perhaps, because of it, Giffen continued to put new ideas and concepts out into the world until the very end. “It was so sad though, because Keith had done one of his periodic sours on comics, and said he wouldn’t do them anymore, but in the year before he died, he was up and ready to get back to work,” Doran says. “That’s why he was finally getting into social media and stuff, and he’d been asking me about how to self-publish and do Patreon and things. He was ready to work again.”

* * *

The work Giffen leaves behind, however, is staggering by any measure. More than 1,600 comics over the course of nearly 50 years; created or co-created dozens of enduring comic book characters, several of which have been featured in animation and feature films; and has produced a body of work that has entertained and inspired his fans and fellow creators for generations, which he did all on his own terms. “I suspect Keith would have been equally creative in any media he worked in,” Paul Levitz notes. “His mind was just that wild. Certainly, he connected well to comics in ways that were influenced by the comics he'd read and loved, but he just was an idea factory.”

Grant Morrison, an innovative writer who cites Giffen as a formative influence on their work, and who was also tapped by DC to revitalize the Justice League after a prolonged sales slump, marvels at the quality and quantity of his comics bibliography. “I didn't know Keith well, but I liked him a lot,” says Morrison. “He had a wicked dry wit and a relentless talent for invention. He struck me as an artist who was outrageously prolific as a function of his being! Like some others in comics—Rian Hughes, Brendan McCarthy or Kevin O'Neill spring to mind—exercising his talent was like breathing for Keith and it seemed to me he lived to draw, create stories and make characters. For that reason, like so many abundantly creative minds, his constant output meant that his work was often taken for granted as part of the general texture of the last 40 years or more in comics.”

Longtime creative partner J. M. DeMatteis, for one, never took his friend for granted, and is confident of Giffen’s place in the comics pantheon. “Keith reveled in his image as a curmudgeon, a surly malcontent, but that shell masked a big, generous heart. And the more you got to know the guy, that more that big, beating heart became evident.

“It was a delight collaborating with Keith. And I’m sure most of his collaborators would say the same. Giffen was sui generis. A one-of-a-kind mad genius whose impact on comics will be felt for many years to come. I’m forever grateful to Andy Helfer for throwing us together all those years ago.”

But perhaps Colleen Doran puts it best. “Keith always claimed he wouldn’t be remembered. Boy, I wish he was alive so I could go ‘Neener Neener’ at him.”

Bwa ha ha!

The post Keith Giffen, November 30, 1952 – October 9, 2023 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment