So... Osamu Tezuka. What’s his deal, anyway? Anyone ever heard of this cat? I think he may have done a couple things.

Humbling, as a reader and certainly as a critic, to face that edifice: a huge granite monument blocking the horizon. The chisel in your hand seems a very small instrument indeed placed in the frame with that vast boulder. Such dizzying scale. The best one can do, perhaps, is to pick a corner and begin chipping away.

Our subject today is a new publication, One Hundred Tales, from Ablaze - "Hyaku monogatari," if you’re feeling fancy, translated by Iyasu Adair Nagata, with English lettering by Aidan Clarke. Originally presented in four long chapters across the second half of 1971, in the pages of Weekly Shōnen Jump. The story takes its name from the popular practice of telling ghost stories as a party game, which apparently then became a cornerstone practice in art and literature that endures to this day. Japan loves ghost stories, and they remain one of the country’s more significant cultural exports.

One Hundred Tales, however, is no horror story, despite having taken primary influence from one of the most famous horror stories in the western literary tradition, that of Faust. Although there are certainly eerie passages and fantastic sequences, the story itself isn’t trying to scare, or even admonish. In most iterations, it's a cautionary tale. Certainly that’s true of Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, which despite its author’s heretical reputation remains a text thoroughly swaddled in the Christian tradition and culture. (Marlowe’s is the version I’m most familiar with, having taught the text.) Faustus conspires with devils out of greed - greed for knowledge, for power, and for life. But ultimately he is still all too mortal, and at the end of his life must face the certain consequences of having consorted with such diabolical agents. The elemental irony of the story is that he could have been saved from this ghastly fate at any point, had he merely possessed the capacity for genuine faith - but such seemingly trivial knowledge is forever beyond the grasp of the narcissist Faustus, and he suffers accordingly.

Tezuka’s version lacks the Christian framework so integral to most retellings of the story. His Faust figure, Ichirui Hanri, is no great egomaniac - merely a hapless accountant, a samurai courtier unwittingly a party to his master’s embezzlement and sentenced to commit seppuku for the infraction. Whereas our Faustus conjures demons from boredom and ambition, Ichirui is a desperate man as he pleads with the demons of his realm for a way out of this certain bind. Accordingly, he’s not answered by any kind of devil, but by a yōkai named Sudama. While I’ve never pretended to be an expert in Japanese culture, I know the yōkai concept doesn’t map onto western notions of devils, always tricking people into turning their backs to the face of a loving God. Our spiritual tradition is far more punitive, I can say for certain. Absolute valuations of good and evil aren’t quite the yardsticks across the way.

Still, despite the differing motivations, Ichirui is almost as venal. Sudama offers him three wishes, and he goes for the usual slate of demands: he wants a new life, the love of a beautiful woman, and to rule his own kingdom. She grants all three wishes, in her turn, even if events don’t leave him quite where he intended.

What always gets me about Tezuka, just about all the Tezuka I’ve ever read, is the contrast between the tone of his stories and the tone of his storytelling. This is by any standards a heavy tale, filled with heavy themes and uncanny subject matter, but the actual telling of the story is light. Tezuka’s figures are expressive, elastic, fundamentally cartoon characters despite their context. There’s a give and take throughout the narrative between the close-up action of the figures interacting in scale with one another and the larger context of landscape and setting. This is something Tezuka does better than just about anyone, and he does it consistently throughout the present volume. As a reader, it makes for disarming effect, suddenly pulling away for establishing shots of such pronounced beauty and grandeur as to make the figures seem small and almost petty.

Early in the book, for instance, Sudama takes Ichirui to get a potion to change his face, in a cave nestled deep at the heart of the most breathtaking scenic mountainside you’ve ever seen. Against this monumental splendor, even a venerable yōkai such as Sudama is merely a blot of ink. It’s two fundamentally different kinds of drawing, and there’s something always just a little bit disconcerting in that juxtaposition. It’s not an effect you see particularly often in western cartooning. Barks did it on occasion, in his longer adventure strips, pulling out for a splendid exotic landscape or windswept coastline to contrast against his stolid ducks trudging away in the corner of the panel. Cerebus made use of the technique as well, eventually bringing in a guy whose sole and entire job was to do the back-breaking work of drawing impossibly gorgeous scenery against which the talking aardvark could rail. Tezuka had assistants, too, but you don’t often see them credited, which—we should be blunt here so as not to be misunderstood—is a singular moral failing of the production model that no one seems especially anxious to remedy.

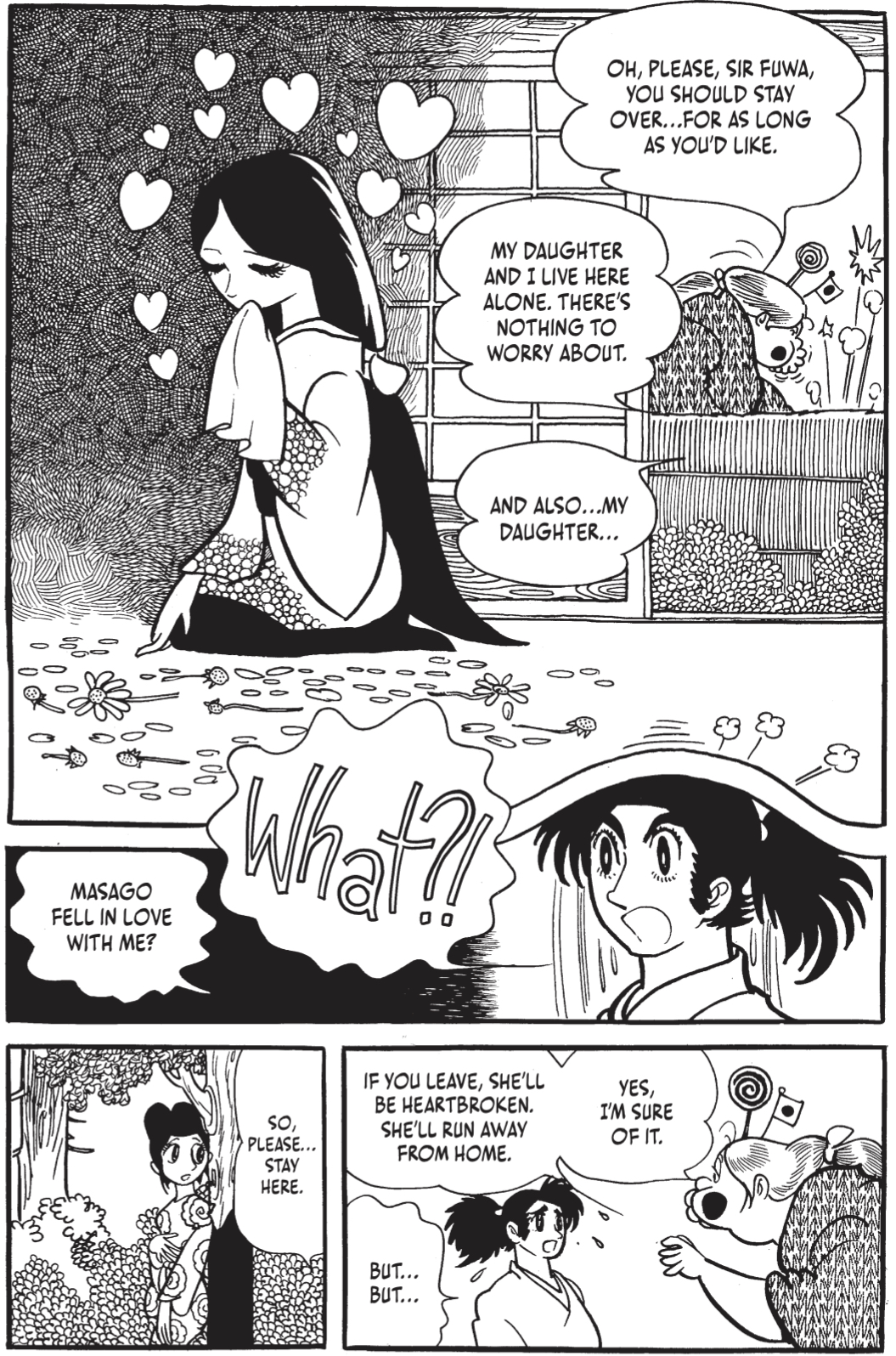

Ichirui’s first ambitions with his new life and body are small, and his adventures disastrous. He wishes to see his daughter again, but is unprepared for her to fall in love with this strange samurai who wants to spend quiet time together. There’s some slapstick too in the form of Ichirui’s widow, a corpulent figure of mockery, every bit the shrewish ballbuster you’d imagine - fawning over the new arrival, she casually states “my husband never really existed anyway.” Despite the source, it seems a fairly accurate dismissal of a man who did not enjoy his life to any measurable degree. The depiction of the widow is regrettable, but of a piece with its era, so caveat emptor.

Then Ichirui makes the mistake of falling for another spirit, Tamamo no Mae. A powerful fox who lives at the top of Fear Mountain, surrounded by spirits and ghosts from across the world. Now, friend, we have all in our lives been “hard up,” but I assure you that even your humble critic has never been sufficiently “hard up” to climb to the top of Fear Mountain to court a demon. A regrettable decision, even as it gives Tezuka the opportunity to draw page after page of horrendous spirits cavorting against the inky darkness of the netherworld. Christopher Lee shows up in this sequence, because even at his most solemn Tezuka was never above inserting random pop culture references into the flow of the narrative.

Of course, just as Sudama warned Ichirui that the beautiful fox spirit would try to devour him, the beautiful fox spirit turns on Ichirui almost immediately, leaving him to be rescued by Sudama. He’s behaved foolishly: “you’re no different from the way you were before!” Sudama says. “A coward! A sucker! I gave you a brand-new life! Why aren’t you trying to do better?”

Where One Hundred Tales deviates from the source is in the disposition of our protagonist. Our conventional Faust is inevitably a fellow who refuses to change, who refuses to grow beyond his own narrow vantage despite seeming to hold the circumference of the world in the palm of his hand. Ichirui, on the other hand, makes a deal for a new life and, with a bit of badgering from Sudama, actually makes good on the challenge. After initial stumbles, Ichirui marches into the wilderness, builds a cabin, and lives off the land for a few years. Learns how to use the sword he carries around for show. He even manages to find himself in an action sequence, helping a local lord’s daughter being held for ransom. Three years in the mountains is apparently sufficient time to turn a craven bureaucrat into a strapping rōnin. Eventually, with Sudama’s help, he finds a vein of gold underground and uses it to buy his way into the service of that same petty lord. He reasons it a simpler manner for an ambitious man to rise in the service of a small court than to acquit oneself in a larger arena.

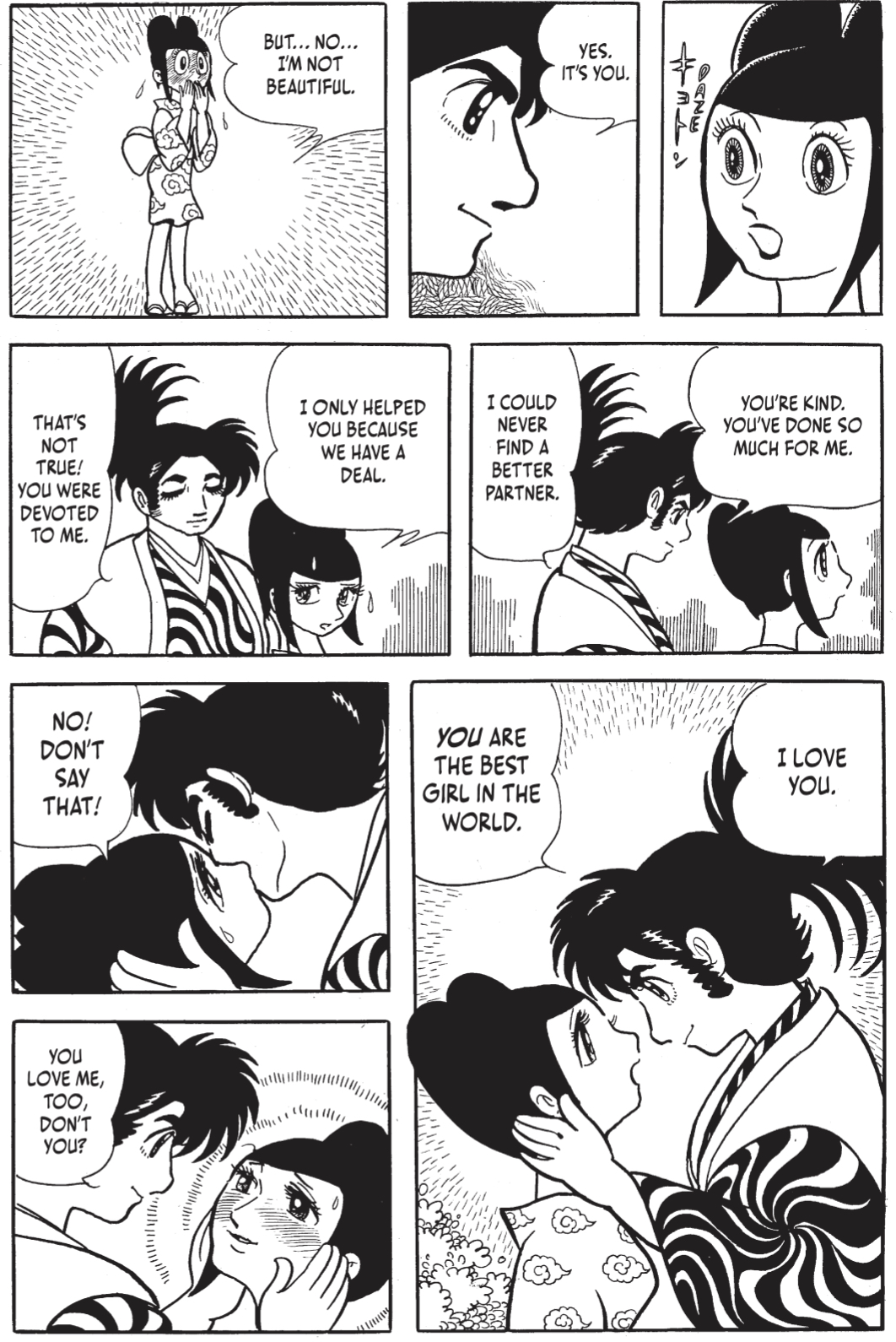

Sudama, despite misgivings, eventually changes herself in response to her changing subject. “Do witches... ever fall in love... with a human?” she muses to herself. “No. Impossible! But... am I different?” There’s that specter of change again, perhaps the most difficult question in the human experience - can a person change? What does it mean to change? To be changed? Some of Tezuka’s greatest works go at this question directly - Ode to Kirihito and Buddha, to pick two of the heaviest examples in the corpus. These are the heaviest questions art can answer. Most Fausts are frustrating creatures precisely because they refuse to change. But living together changes both Ichirui and Sudama. Seeing him raise himself to betterment deepens her own commitment. The question of whether or not demons can actually change opens a new dimension for Faust stories.

The final stretch of the story expands the scope, bringing mind comparisons to another such epic of thwarted ambition: Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (1957), another supernatural story transplanted from western soil to Japan, one kind of ghost story changed into another. Seeing the uselessness of his new liege, Ichirui deposes his lord in a coup, taking the throne of a newly wealthy land with the help of a peasant army. Even here, we see Tezuka’s variable tone shifting - Sudama makes a potion to give the peasant army fighting spirit, and of course the potion requires a lot of boogers. Did the book truly need an extended nose-picking sequence? Well, it has one. Far be it from me to question the master. The potion turns the peasant army into a legion of Popeyes, Seger-esque grotesqueries chomping on corncob pipes and heaving boulders with the same distended forearms.

The slapstick of nose-picking and endless homage is inextricable from the epic scope, vast fields of soldiers sweeping across fields and mountains, armies conjured effortlessly from the febrile landscape. Ichirui succeeds in his ambitions, until he doesn’t. His problem is that he lets the deposed lord live, and despite his general uselessness, the villain is still able to gather help sufficient to depose his rebellious lieutenant. Ichirui finds himself once more on the chopping block.

And it is in these final pages that Tezuka reveals the heart of the story. Sudama appears to him once more, as he awaits his death, and informs him that she can indeed save him again, just as she has done throughout. She just requires that their contract remain unfulfilled, that he remain unsatisfied. All he has to do is proclaim that his wish remains ungranted and she can save him. She pleads with him to deny his satisfaction, to continue to live. But he refuses: he asked for the love of the most beautiful woman in the world, and he refuses to deny it even with his life hanging on the line.

Laundering the most macabre fable of faithless ruin into a parable of romantic fulfillment - not a bad trick. For anyone else this would stand as a defining masterpiece, for Tezuka this was four months in 1971. Another chip off the endless mountain. My goodness, but this Tezuka fellow certainly knew a few things!

The post One Hundred Tales appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment