When I lived in midtown Toronto along St. Clair Avenue West, my next door neighbour and I would dissect the events that unfolded in our strange pocket of the city.

When a funeral procession was accompanied by a beefy police escort, we turned to the news for answers and discovered that a gang member had been granted a prison leave to attend his father’s burial. On another occasion, during a knifing that transpired along an alleyway that bisected our apartments, we waited for days to see if the municipal government would send someone to wash the blood stains that not even the rain could wash it away (they did not).

But my favorite thing to talk to D. about was the dismal state of the world; our discussions would also turn to the subject of keeping the creative flame alive and how alternative comics could buoy cynics against the great heave toward cultural and spiritual oblivion.

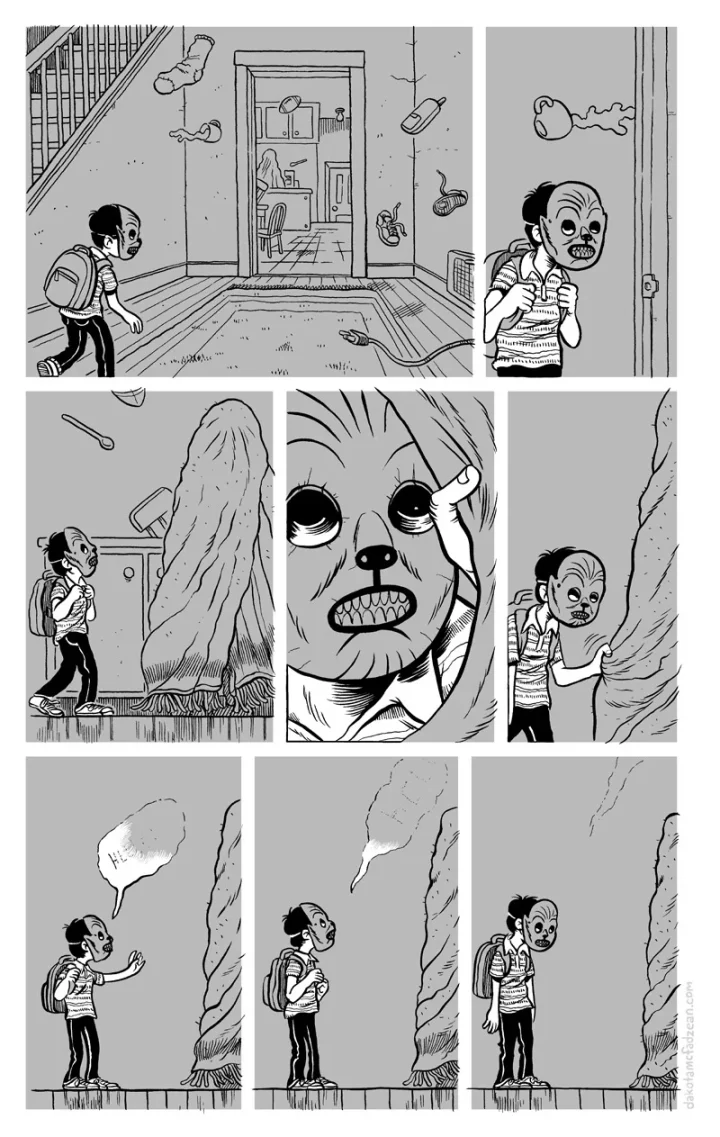

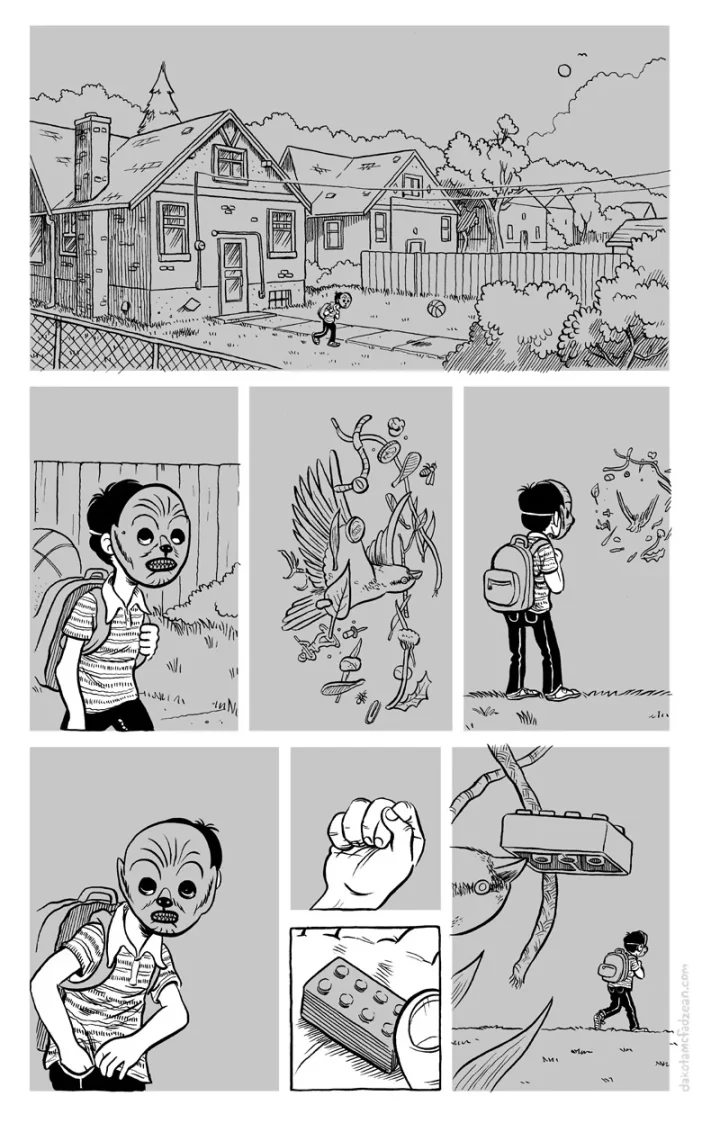

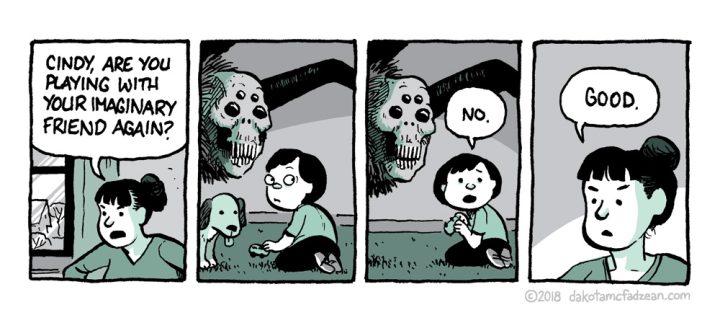

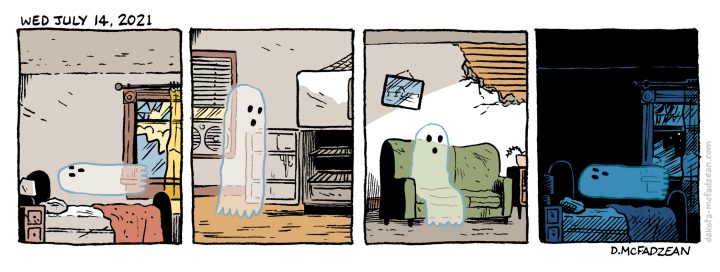

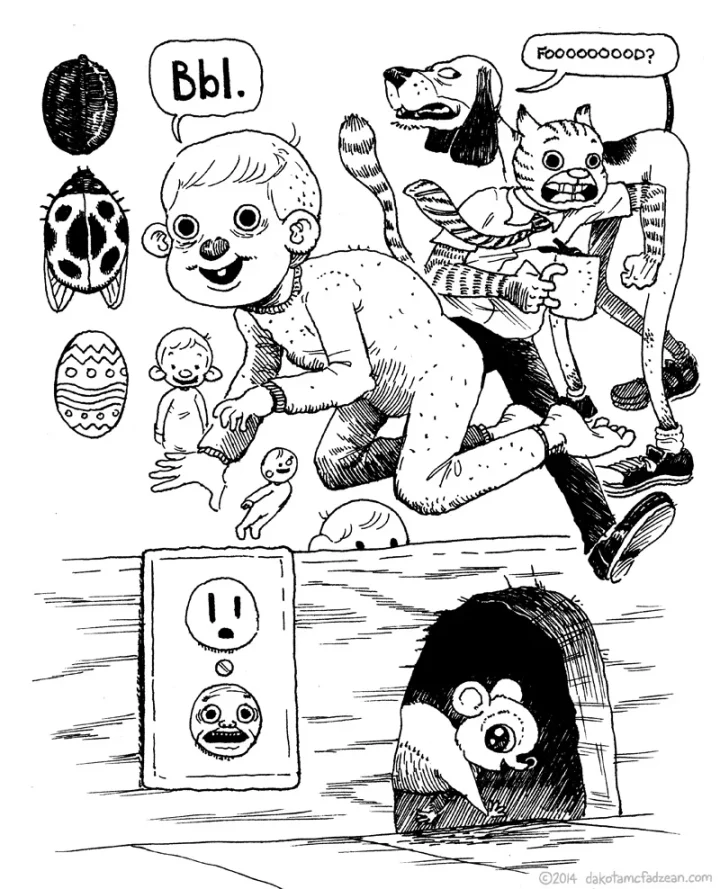

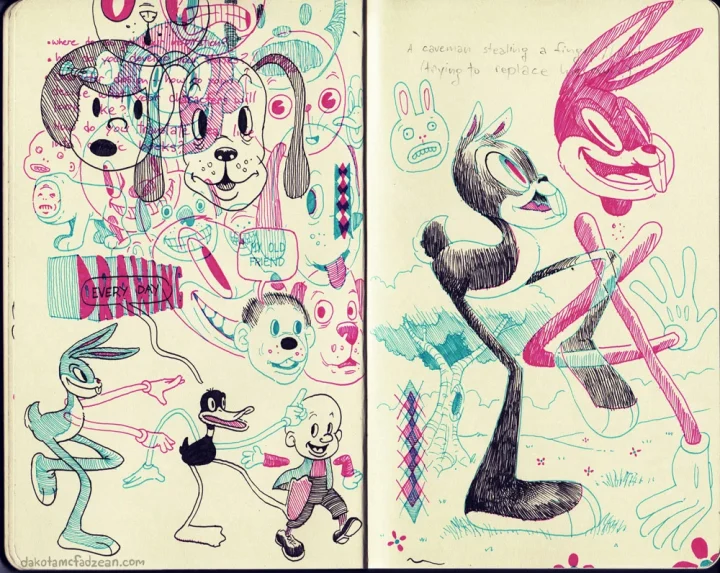

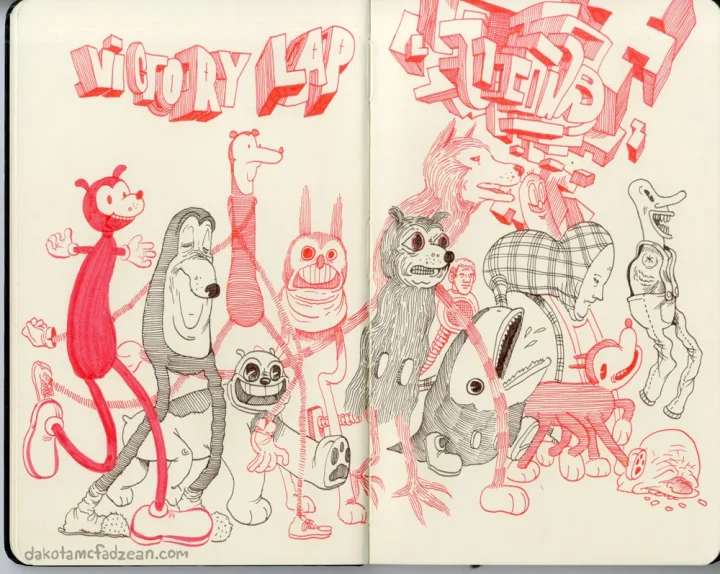

Born in Regina, Saskatchewan, D. McFadzean graduated from the Center of Cartoon Studies and put his training to use quickly, landing coveted cartooning opportunities with The New Yorker, Mad Magazine, and Funny or Die, before branching out to do storyboard work for DreamWorks and Netflix. His comics work is defined by a blend of surrealism, horror, and comedy, often in service of withering social commentary.

McFadzean’s comics include To Know You’re Alive, Don’t Get Eaten By Anything: A Collection of the Dailies 2011-2013, Other Stories and the Horse You Rode In On, and Hollow in the Hollows. His most recent release, Fever Dream, a graphic meditation on social decay and parenting in the early days of lockdown, was released by Conundrum Press in October 2025. After living in Montreal, Hartford, and Toronto, he now resides in Regina, Saskatchewan with his wife and two sons.

JEAN MARC AH-SEN: Fever Dream is one of several titles Conundrum Press is releasing as part of its 25th anniversary celebrations. These slim, collectible volumes are digest-sized books that will reward the repeat reader’s appreciation of nuance and detail. How did you get involved with the Conundrum 25 project? Was deciding on what your contribution would be for the series a relatively easy task?

D. MCFADZEAN: Conundrum Press has been publishing my comics since 2013, and so Andy Brown [Conundrum publisher] asked me to contribute a piece to the series. This was a couple of years ago now. I think a few books in the series had been published at that point. Andy had it in his head that he wanted Joe Ollmann’s book to be #1, and for me to close the series with book #25, which was a huge honour to me.

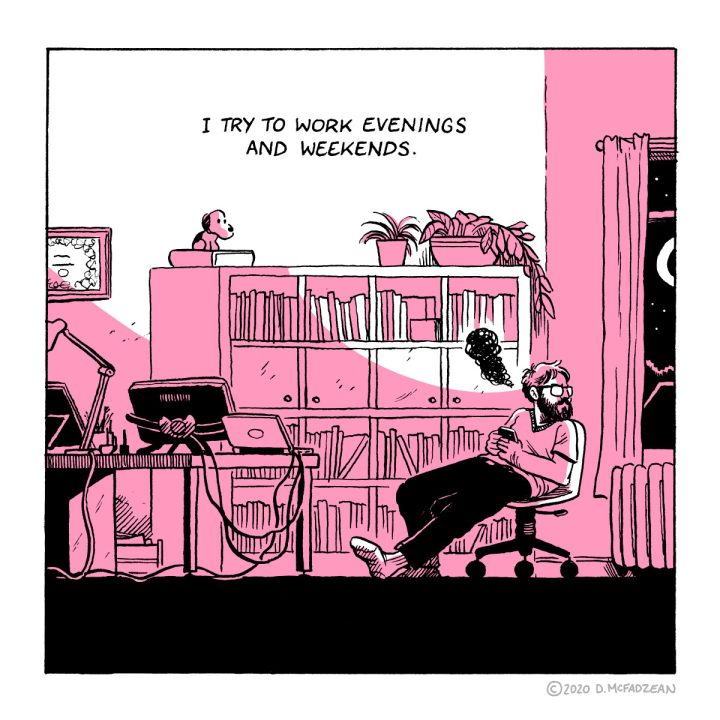

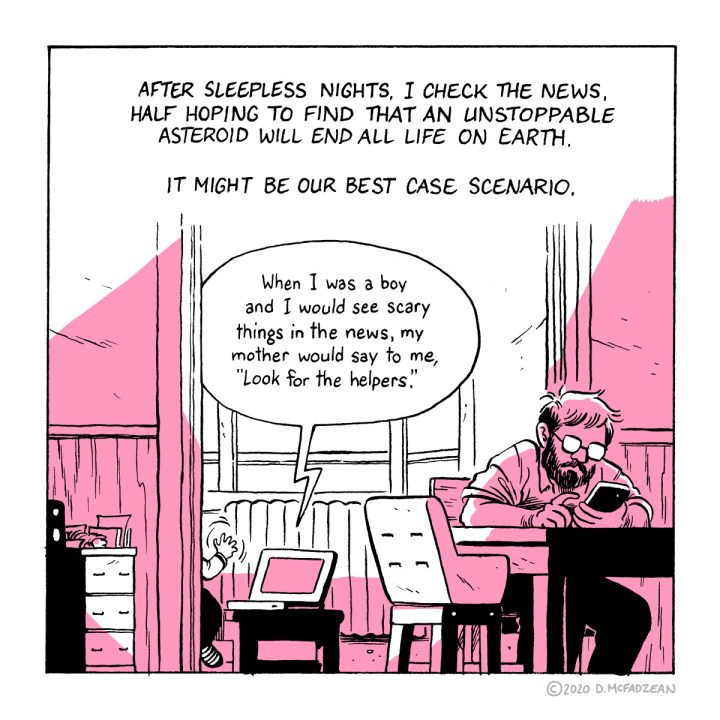

In terms of deciding on what to contribute, I was in a creative identity crisis at the time, which informed how I approached the book. Like many people, I had kind of fallen apart during the pandemic. Between global uncertainty, raising kids, the death of my mom, and moving across the country, I ended up taking an unintentional sabbatical from cartooning. I went from drawing every day to rarely drawing ever. I was drawing less than I had since I was five years old, which felt extremely weird and rudderless.

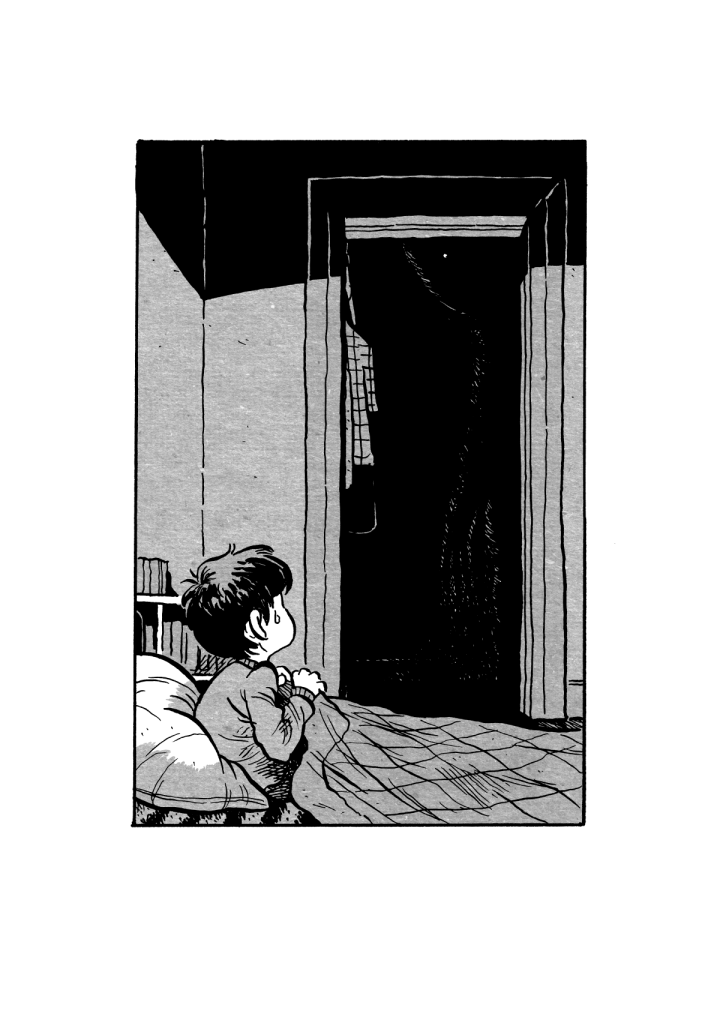

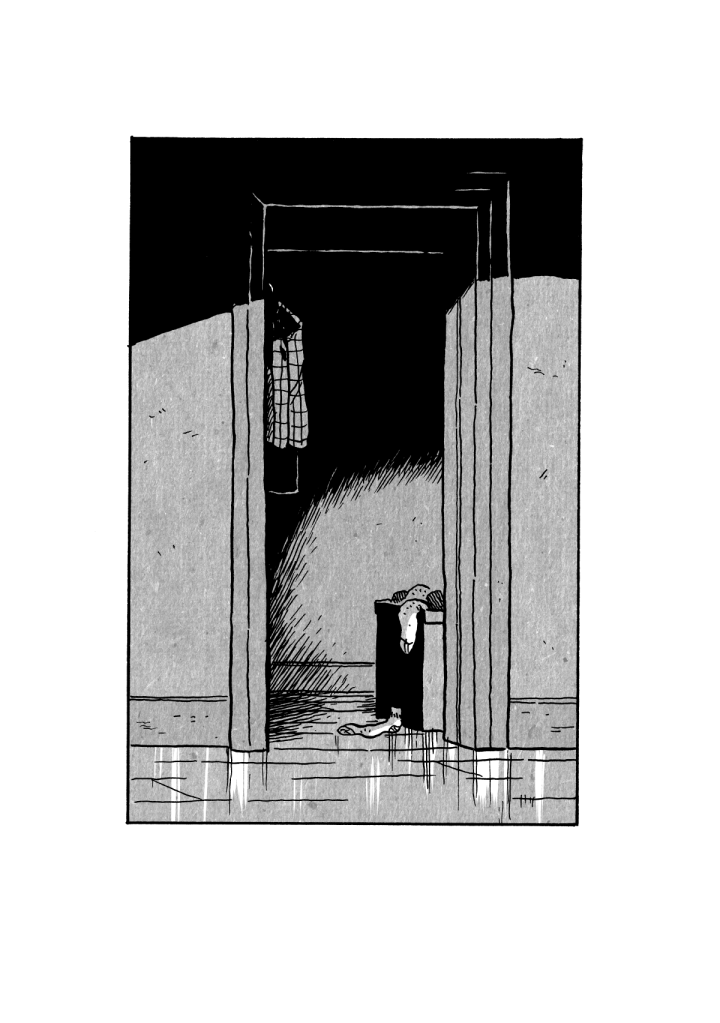

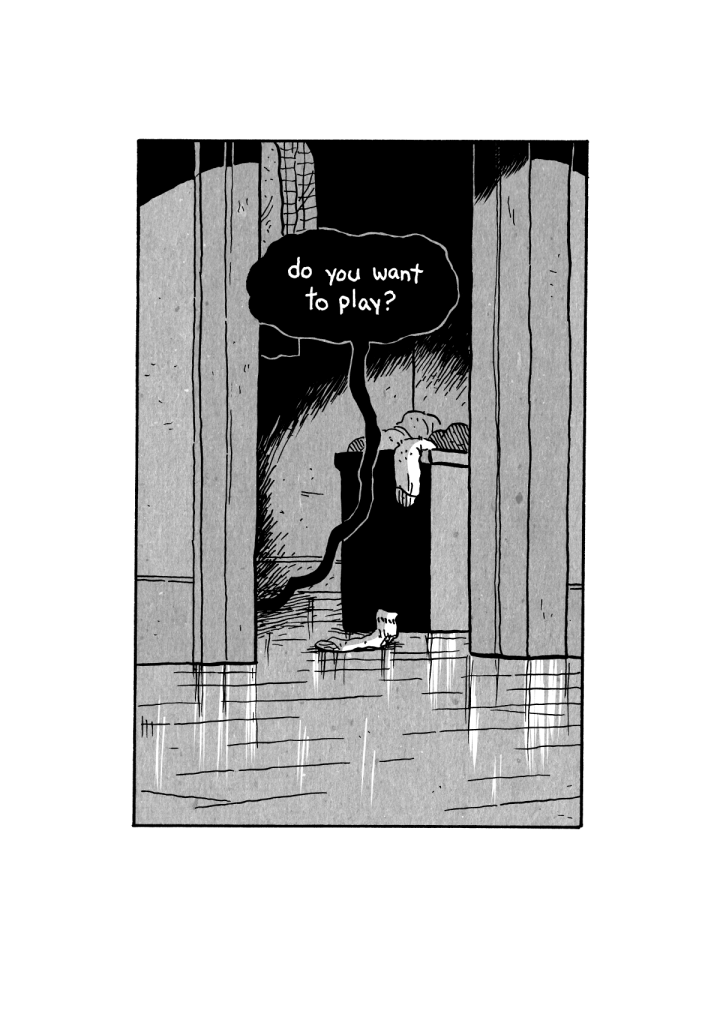

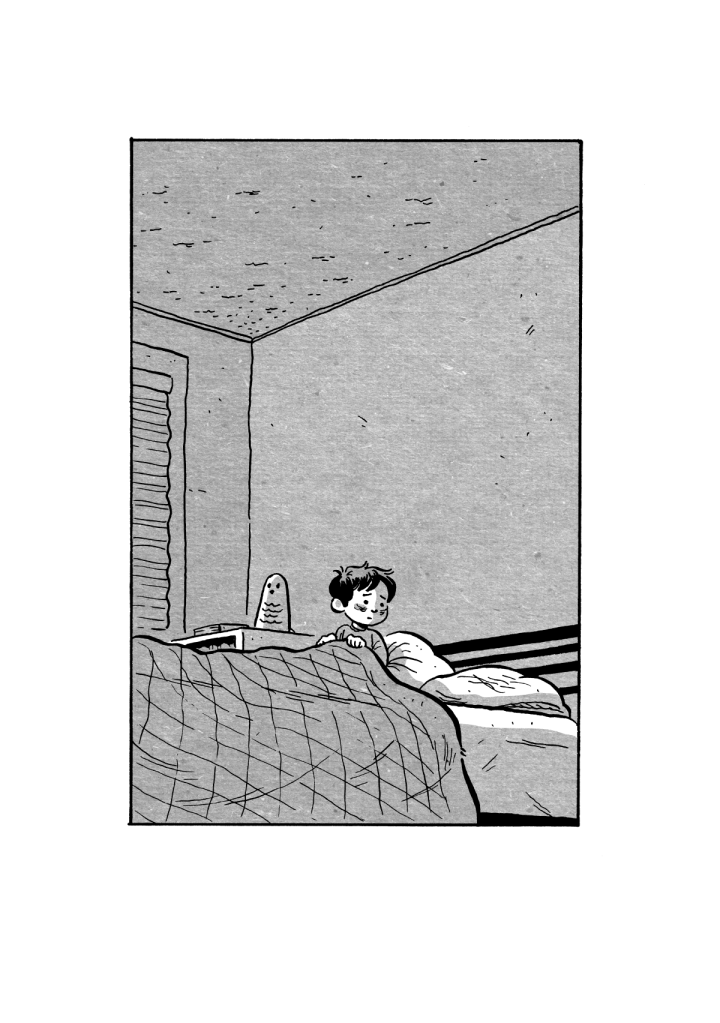

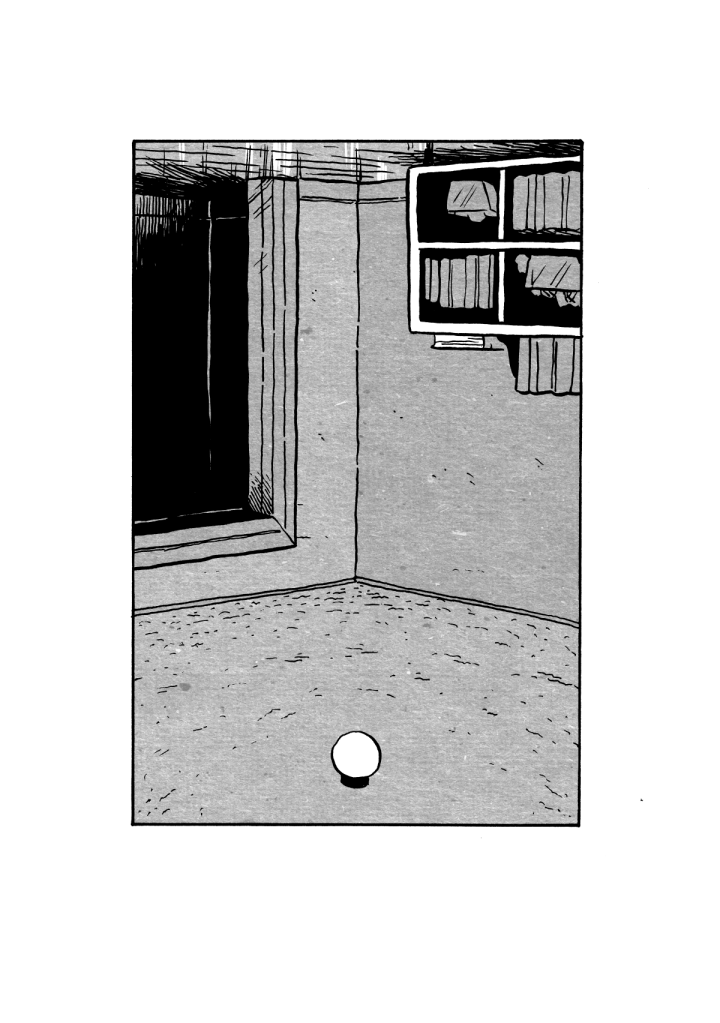

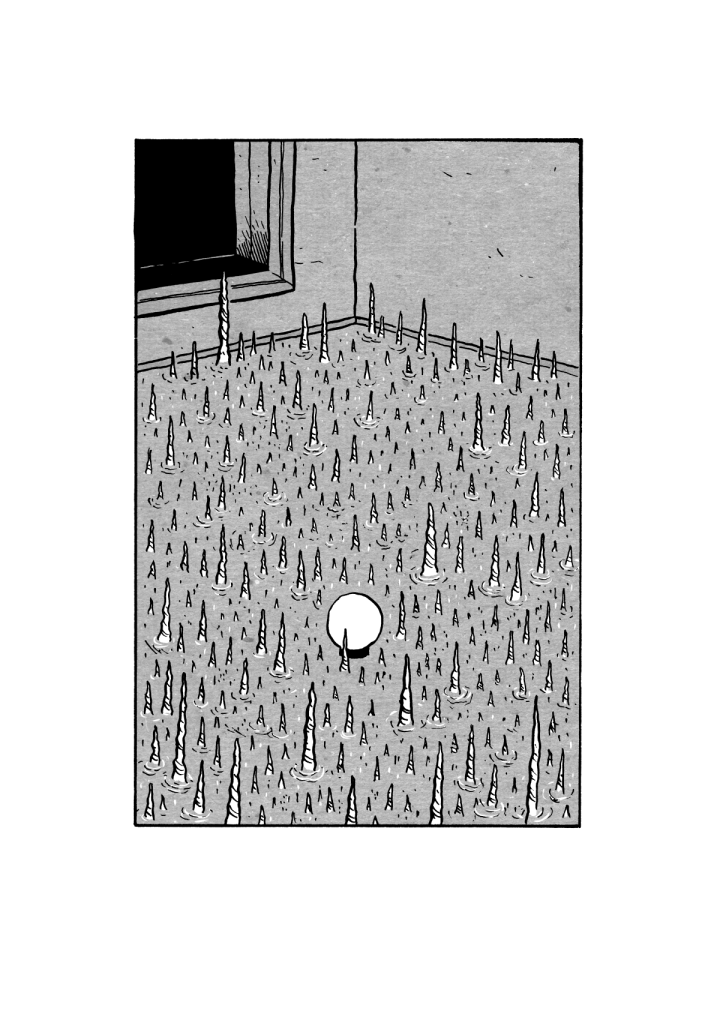

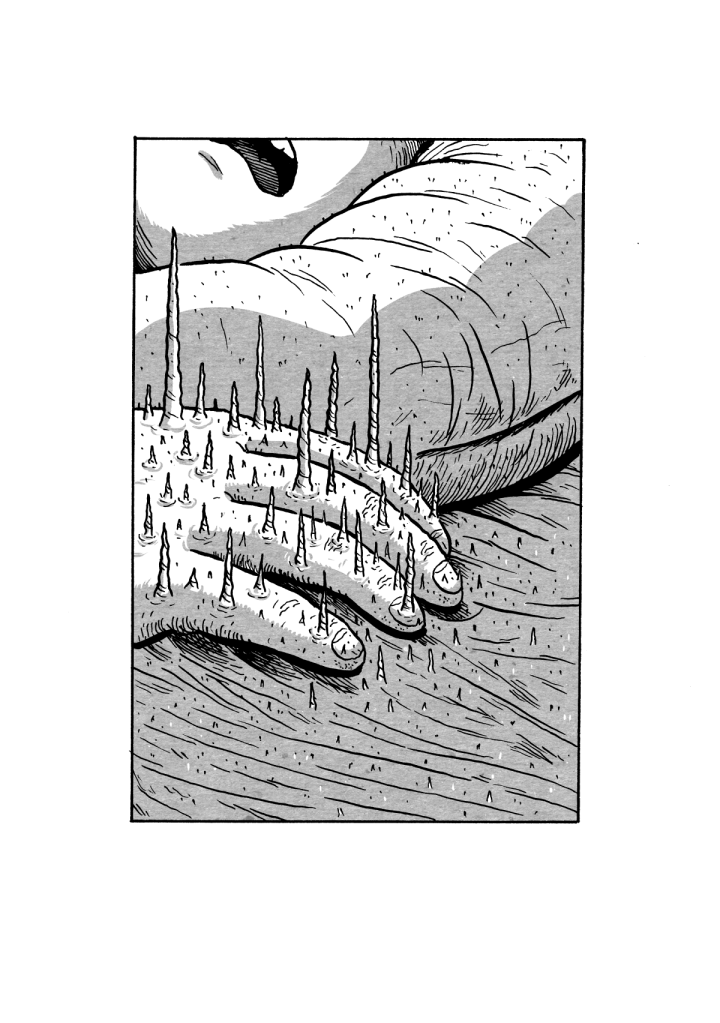

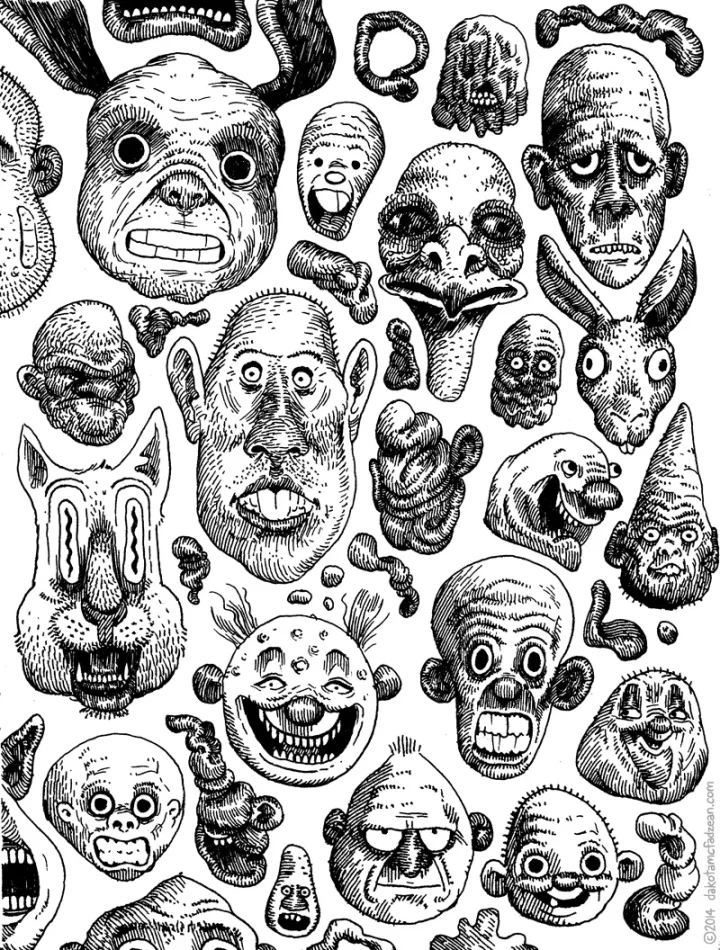

I had a few different book ideas I was outlining for this project, but I settled on Fever Dream for a few reasons. For one thing, I already had fevers on the mind because kids bring home so many illnesses in the winter. I was living a lot of nights similar to the one in the book, which caused me to reflect on my own memories of being sick as a kid, and how it differed from the perspective of being a parent. After researching other people’s fever dreams online, I was surprised to discover a number of recurring experiences and “tropes” that sounded just like my dreams. Things like a sense of shifting size and scale, impossible objects, impossible tasks, looping countdowns, a feeling of permanence, smooth textures that become uncomfortably rough, and more.

Trying to translate some of this into a comic seemed like an interesting challenge, (maybe even an impossible task). It also made for something that wasn’t too plot-driven, and would give me room to draw and play with imagery, textures, and rhythms. This felt manageable with where my head and skills were at the time.

You use a full-page single panel structure for the entire book, and are able to create some visually interesting effects that are reminiscent of zoetropes and flip books. Can you talk about what attracted you to rendering the book entirely in this format?

I believe Andy Brown pitched the series to me as each book being one panel per page, and approximately one hundred pages. I love a good constraint when working on something; it keeps me from getting too in the weeds with endless possibilities — it forces me to be more inventive.

There’s a steady rhythm when you only have one panel on each page, and this seemed conducive to playing with time loops and repetition as a way of simulating the feeling of a dream. Most of the pages contain the image within a panel, but occasionally this is broken with a full-bleed image, which I hoped would convey the kind of expansiveness of dreaming.

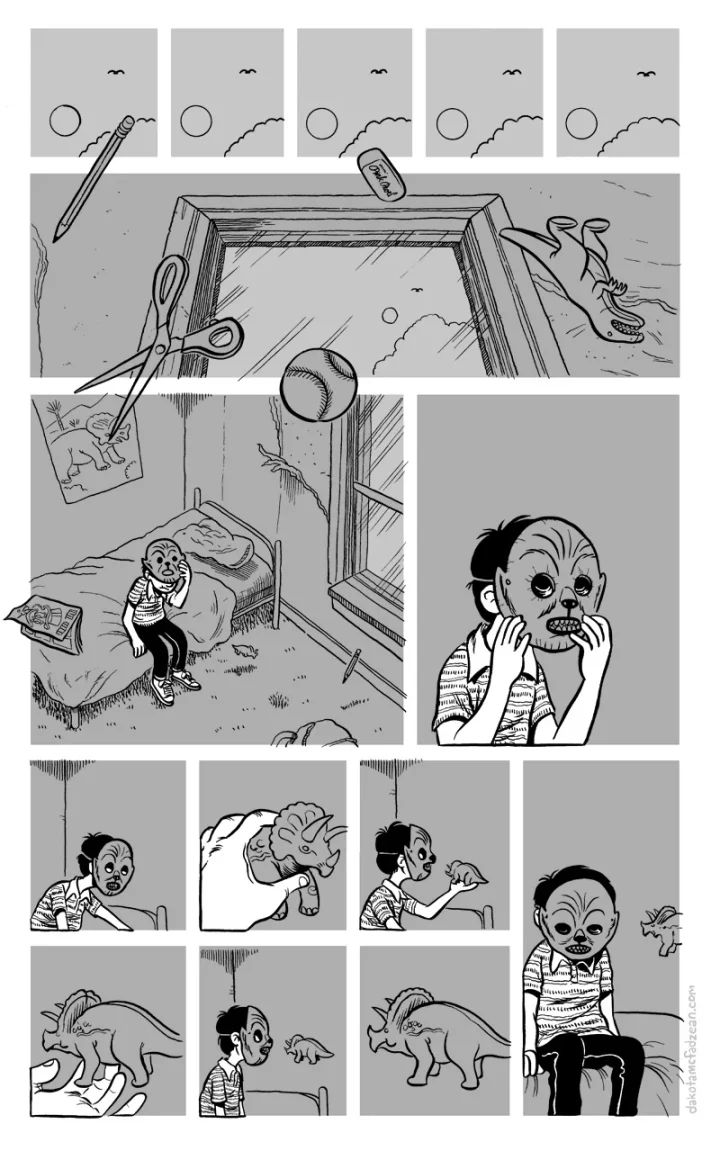

As for the zoetropic effects, I love it when wordless sequences in comics seem to animate with the movement of the reader’s eye, and it’s something I try to do whenever it fits the story. It’s one of those things that make comics feel like magic—they become alive when activated by the reader.

Fever Dream deals with pandemic anxieties relating to child rearing and the over-indexation of virological data that was in the media following the worldwide shutdown. What do you remember the most about this period in your life and what was it like to revisit it through the lens of narrative?

I mostly remember feeling overwhelmed, frustrated, and tired. It’s easy to forget now just how confusing the early days of the pandemic were. Information was changing daily, misinformation was rampant, and it all felt impossible to navigate. I sometimes felt like the world was ending, and in some ways, the world as we knew it did end. Covid might not be on my mind as much anymore, but now everything is too expensive, everything feels less stable, and there’s been this scary shift towards fascism.

I’ve always been prone to worrying, and the act of raising kids is full of worry at the best of times because you become more aware of just how fragile and brief everything is. Fever Dream is an attempt to process, or maybe exorcise, some of those feelings, both real and imagined. The specifics of the child character’s illness are left ambiguous, as is the news the parent characters are reading on their phones. It’s a bit of an indulgence in all the ugly uncertainty of the future. On some level, I’m making fun of myself for worrying so much about things I can’t control.

That said, there’s something very immediate and present about having kids, and I think I’ve gotten better at being in the moment. I’ve dedicated my life to putting little drawings in boxes, so it might not surprise anyone to learn that I really, really, like having control. The last several years have helped me understand how little control any of us have over anything, but I can still be present with my kids. I can still help them navigate things as they come. I can still put pictures in boxes to try to make some sense of things.

You were one of the last crop of artists to pass through the hallowed halls of Mad Magazine as a bimonthly periodical that published original content and up-to-the-minute social commentary. What were some of your favorite Mad strips and fold-outs, and was there a sense of momentousness to be published by the magazine?

It definitely felt momentous to be a small part of it. I grew up reading Mad. My dad gave me his old issues to read when I was little (something I’ve since done with my own kids). If I was sick and stuck home from school, my mom would pick up an issue for me. It exposed me to so many different art styles and comedic sensibilities, and it was a huge factor in my desire to be a cartoonist.

The things that stood out the most to me were Sergio Aragonés’ “Drawn-Out Dramas” and “A Mad Look At ...," Al Jaffee’s fold-ins (though I could never fold them very well), and Mort Drucker and Sam Viviano’s movie and TV parodies. I might have loved “Spy vs. Spy” the most. I had a paperback of “Spy vs. Spy” strips by Antonio Prohías, and would pore over his art, completely in love with the look of his textures, shapes, and lines.

I was lucky enough to visit the Mad offices in New York a couple of times and meet some of my heroes, and it was pretty much like the episode of The Simpsons where Bart makes his pilgrimage to the Mad headquarters (“I will never wash these eyes again.”) The Usual Gang of Idiots was as funny and quick witted as you’d imagine, but also so warm and welcoming. Mad also paid much faster and more reliably than virtually every other freelance gig I’ve ever taken. It was the real deal, and it still hurts that the Time Warner suits shut down the New York offices and reduced Mad to being mostly reprints.

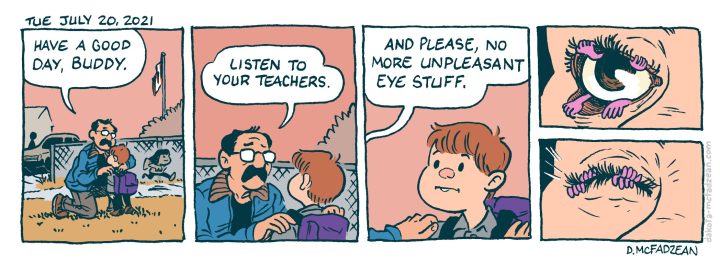

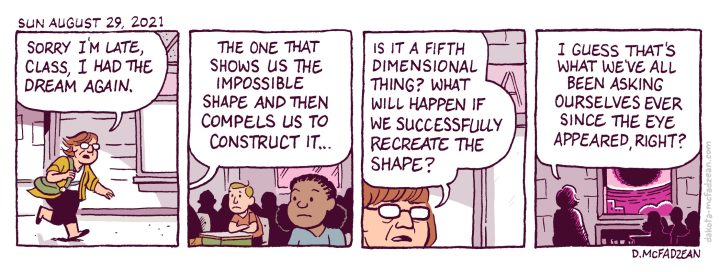

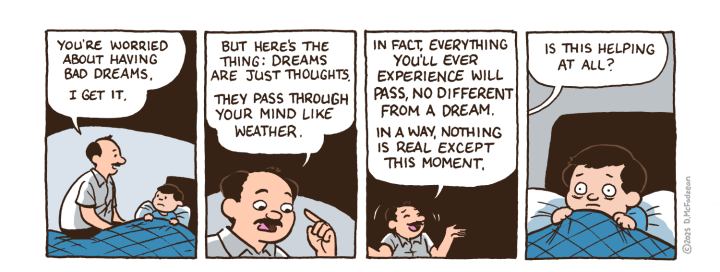

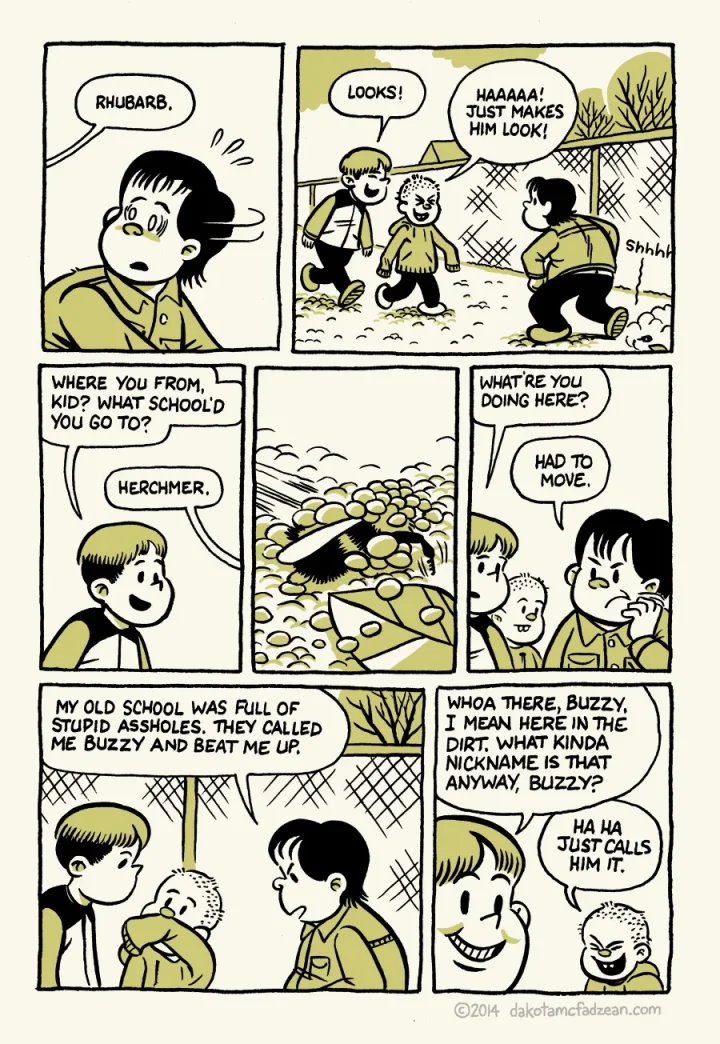

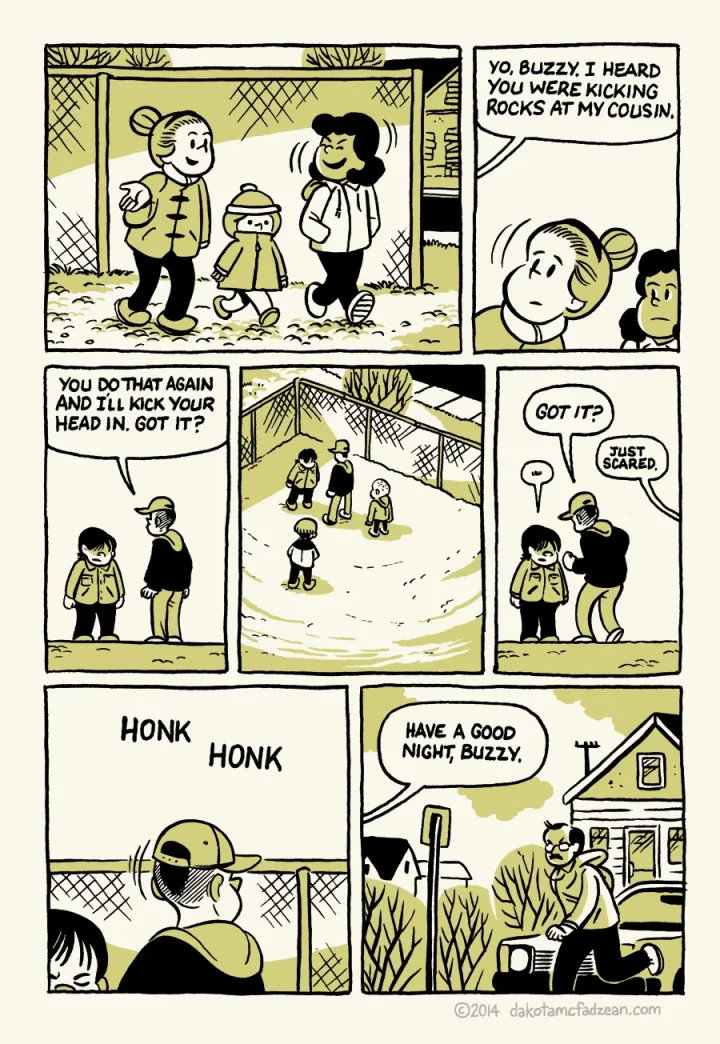

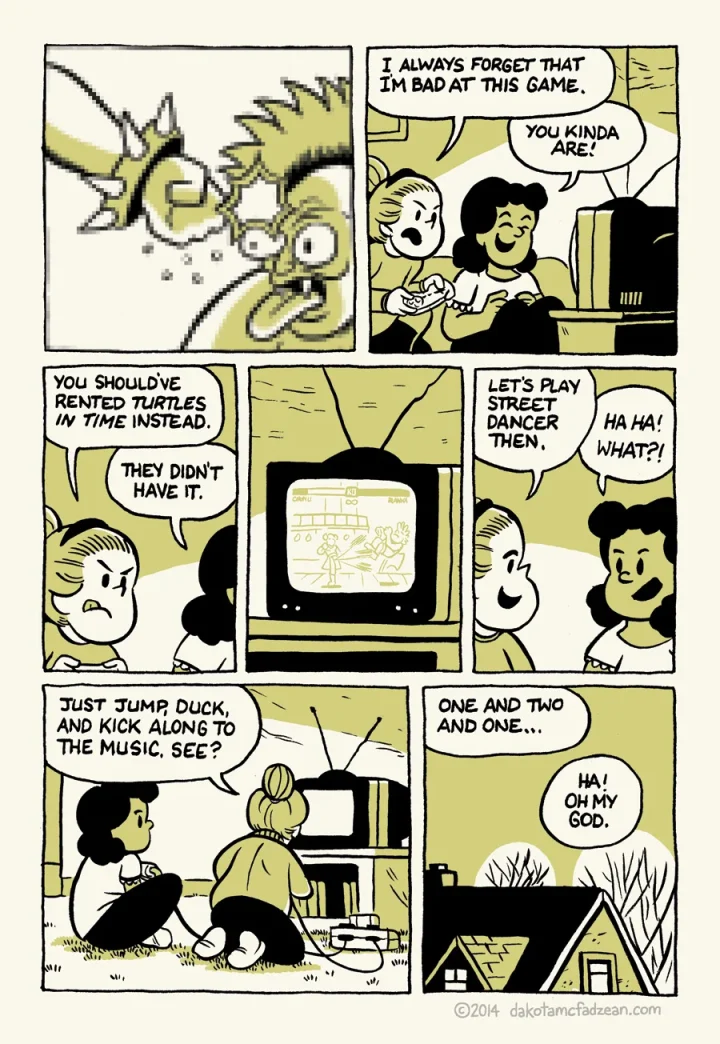

You’ve recently returned to the four-panel comic strip, which appears somewhat regularly on your Instagram account. You honed your ability to tell a story with concision in your projects 8105 and The Dailies, and I’m wondering if you can talk about the different creative mindset you have to be in to create something that works not only with a rigid panel structure, but which operates within a strict publishing schedule. Do you find that you are less hard on yourself or filter your ideas less than if you are working on a long-form project with plenty of lead time? Is the short form comic strip where you can properly field test ideas and panel arrangements?

Yes, I’m definitely easier on myself when drawing quick four-panel strips. They work best when it feels like I’m just playing. I originally started drawing a daily comic as a means of improving my cartooning and writing, and there’s a disposability to doing something every day. There’s room for spontaneity, and if an idea sucks or doesn’t quite land, oh well, there’s always tomorrow.

I drew The Dailies for six years, and stopped because it was getting too hard to fit in with other projects, kids, etc. It taught me a lot about my cartooning inclinations, and often resulted in reinvestigating ideas in longer comics. Sometimes, I miss the practice of it, which is why I’ll still occasionally make new four panel strips, but I’ve also enjoyed not exclusively making comics every waking hour. Turns out there are other aspects of life that are worth spending time on too.

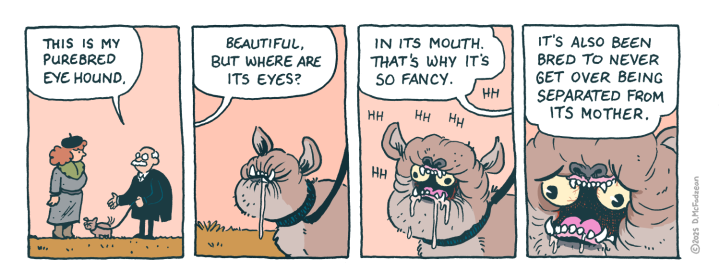

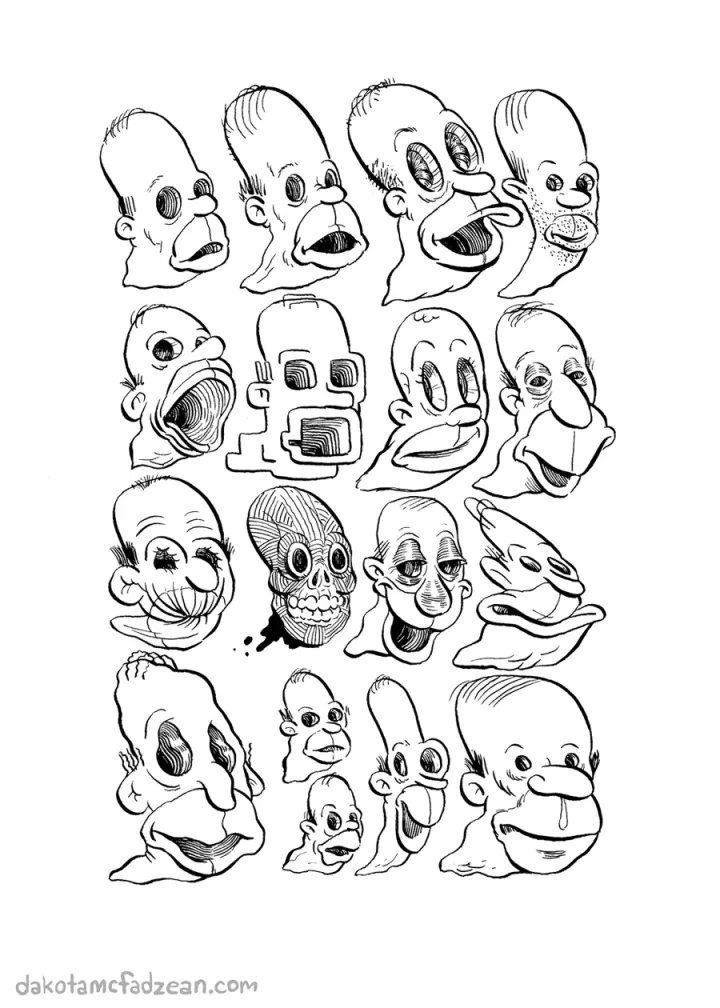

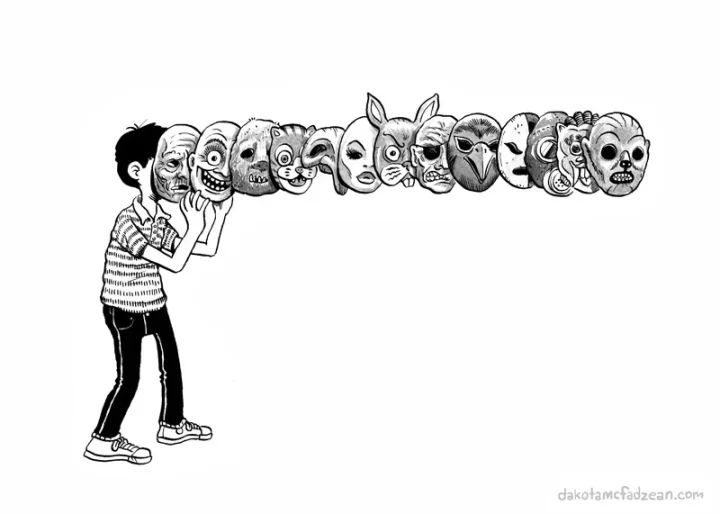

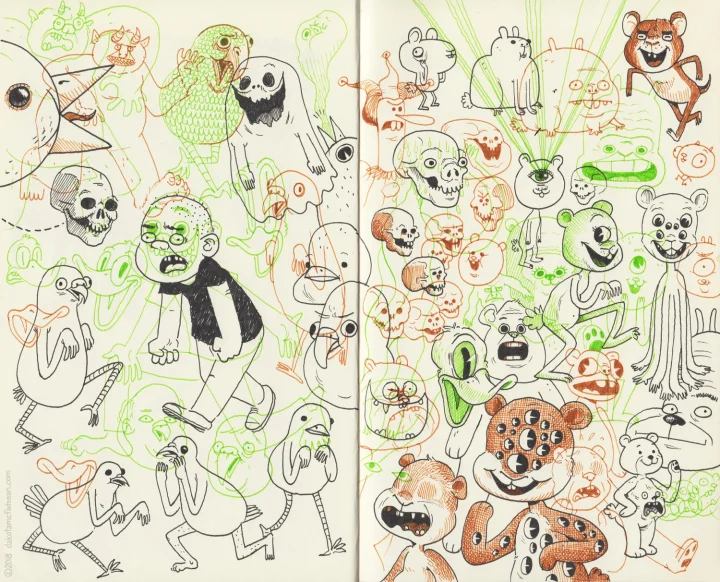

The sensibility in your work I think could be characterized as a merger between black humor and surrealism — if these are accurate descriptors of your work, can you talk a bit about how you hit upon this marrying of tones?

I think the kind of work one makes gradually reveals itself through iteration. It’s a lot of following impulses based on some arcane criteria that can’t be articulated, and over time it slowly becomes a seemingly cohesive body of work.

With hindsight, I can say that I’ve always loved comedy, cartoons, and anything that bends reality. I was also both fascinated by, and overly sensitive to, anything scary when I was little. Nightmares would make me afraid to go to bed because, what if I have that dream again? My dad would encourage me to draw a picture of the dream as a means of gaining power over it, or to “get it out of my head.” A lot of my work is still attempting to do that.

There’s also a lot of overlap between comedy and horror. They’re two extremes of the same spectrum in the way that they attempt to surprise the audience. When I was drawing my daily comics, I was happiest when I was surprising myself, so I’d try to go with choices that were a few degrees removed from the most obvious solution. I know this is kind of contradictory with my desire for control, but comics can be so slow and tedious to make, and I need an element of spontaneity to keep it interesting. Even when I thumbnail a story, I still change things on the fly when inking and penciling — a different line of dialogue, a new connection that could only be made while inhabiting and playing in the page. If I know exactly how everything is going to go, it almost feels pointless to finish.

What were the graphic texts from your early years that left an impact on you? Was there a title that made you think a career in comics was worth pursuing, or a strip that made you impulsively want to reach for a pencil and paper?

There are too many to mention, but I’ve wanted to make comics since I was five. Books were extremely important to my parents, and they made sure that there were always plenty of books, comics, and art supplies available at all times. Most of the stuff that was formative to me is pretty standard for any cartoonist who grew up in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Calvin & Hobbes, Peanuts, and The Far Side were big ones for me. I read a lot of Archie Comics, but especially loved anything drawn by Samm Schwartz and written by Frank Doyle (not that I knew those names at the time. I just knew that the best Archie comics were always about Jughead, and usually had a “vote Samm for class president” poster in the background of at least one panel). I was obsessed with (and terrified of) the Gnomes book by Wil Huygen and Rien Poortlivet.

A lot of TV shows and video games made me want to make something, too. The Simpsons, The Muppets, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Looney Tunes, Dragonball, and more. I loved the gap between the simplistic, abstract 8-bit sprites in NES games compared to the elaborate art in the instruction manuals, and so I’d spend a lot of time trying to draw my own interpretations of the sprites.

One thing I never see anyone mention is The Wonderful Wizard of Oz anime TV series from the ‘80s. Margot Kidder narrated the English dub, and The Parachute Club did the theme song. Watching that show is one of my earliest memories, and I still love everything about it. The character designs and background art are beautiful. It got wonderfully weird at times with the Nome King’s giant underground worm, and the horrifying animation when the characters touch enchanted ornaments and proceed to melt into ornaments themselves. Every time I make something, there’s part of me that still wants it to feel like it exists within that world.

But it always came back to making comics for me because all I needed was paper and something to draw with. Drawing is just so immediate and available. There was no need for special equipment (aside from maybe trying to convince teachers to photocopy my comics so that I could share them with classmates).

We’ve talked a bit in private about how the need or desire to make art may not be felt as strongly in certain years as in others. Can you talk a bit about your most recent struggle to maintain a relationship with your art-making? Did you stop because your body and mind were screaming for some kind of pause from this at times grueling industry, or was the decision to put comics on hold the result of a carefully crafted plan to better invest in yourself for the foreseeable future?

I touched on this earlier, but yeah, I think I just burned out. There was too much going on in my life, and the world, to have the bandwidth for cartooning anymore. I had also made cartooning the centre of my life, which is great for making a lot of work, but not great when it becomes synonymous with self-identity. It was getting unhealthy. No matter how much work I made, it never felt like it was enough; therefore I wasn’t enough. No matter how many cool opportunities I got, they never seemed as legit as the ones my peers were getting. I was already struggling to balance my personal work with paid work and raising kids, let alone taking care of my body or having hobbies, so I was burning out already. 2020 pushed me over the edge.

I wasn’t at all happy about taking a break, and in some ways I still fear that a lot of the opportunities, momentum, and connections I had have dried up. I haven’t done any storyboarding work since 2020. I didn’t table at a comics festival for about five years. But I’m also happier and more balanced than I was before. I make time to exercise and go on bike rides and spend time in nature. I’ve been learning to play guitar, instead of endlessly staring into the horror on my phone. I can’t overstate how wonderful it is to practice something that I don’t need to share or monetize.

The 2010s felt like an upward trajectory for my cartooning, but it was unrealistic for me to expect that to always be the case. My cartoonist friend, Betsey Swardlick, once described the off years as being fallow; you need to let the soil regain nutrients to keep growing things. I like that framing.

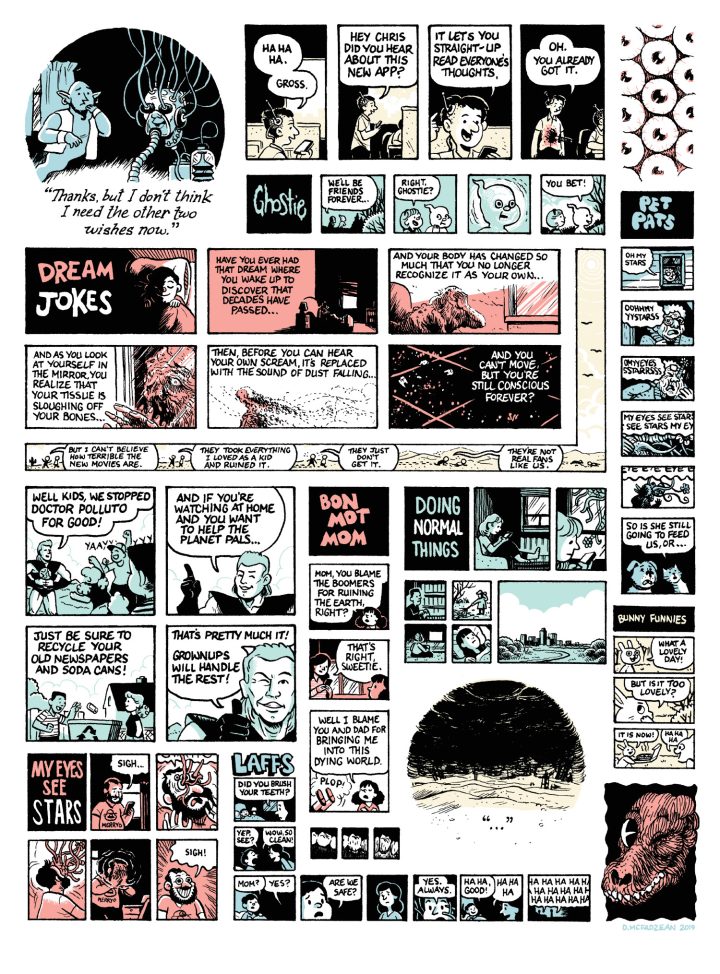

In 2012, along with your fellow Center for Cartoon Studies graduates Andy Warner and D.W., you released six issues of the Irene anthology, which boasted artists from every continent of the world. Can you talk about some of the creative objectives this book was meant to serve, and whether the anthology format would be something you would be willing to take on again?

Our time at the Center for Cartoon Studies set an ambitious, creative momentum that Andy, D.W., and I were eager to maintain after graduating. An anthology seemed like a good way to keep one another accountable and continue making art together. Each of us had overlapping, but wildly different sensibilities, and I think the anthology reflects that.

We rotated our roles each issue, and we tried to bring in other artists whose work we felt was a good fit. But we never really had a defined goal or rubric beyond the quote on the back of each book, which is pulled from an old Yellow Kid strip: “It’s a rainbow of color, a dream of beauty, a wild bust of lafter, ‘an regular hot stuff.” (sic)

We were fortunate enough to get a production grant from CCS to help print the first issue, and we made six issues before our personal and work lives became too demanding to continue. I’m not sure if I could do it again. It’s a lot of work, and much of it coasted on indie comics good will and DIY fumes. Shout out to Matt Moses of Hic & Hoc for distributing and supporting Irene. Maybe we’ll do a one-off anthology for old time’s sake, someday. Irene: Retirement Home Edition.

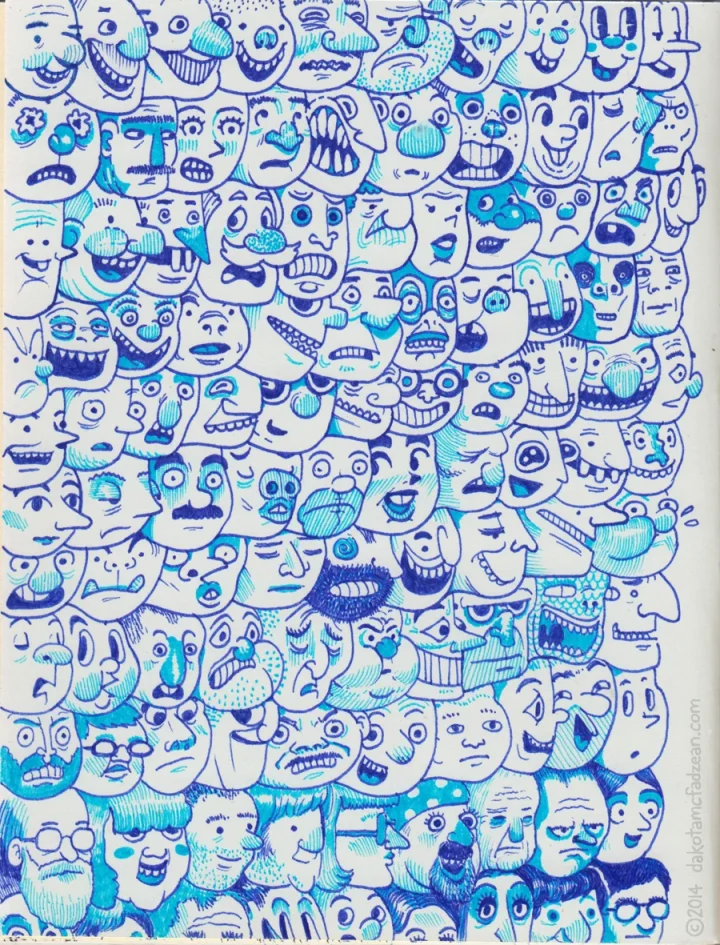

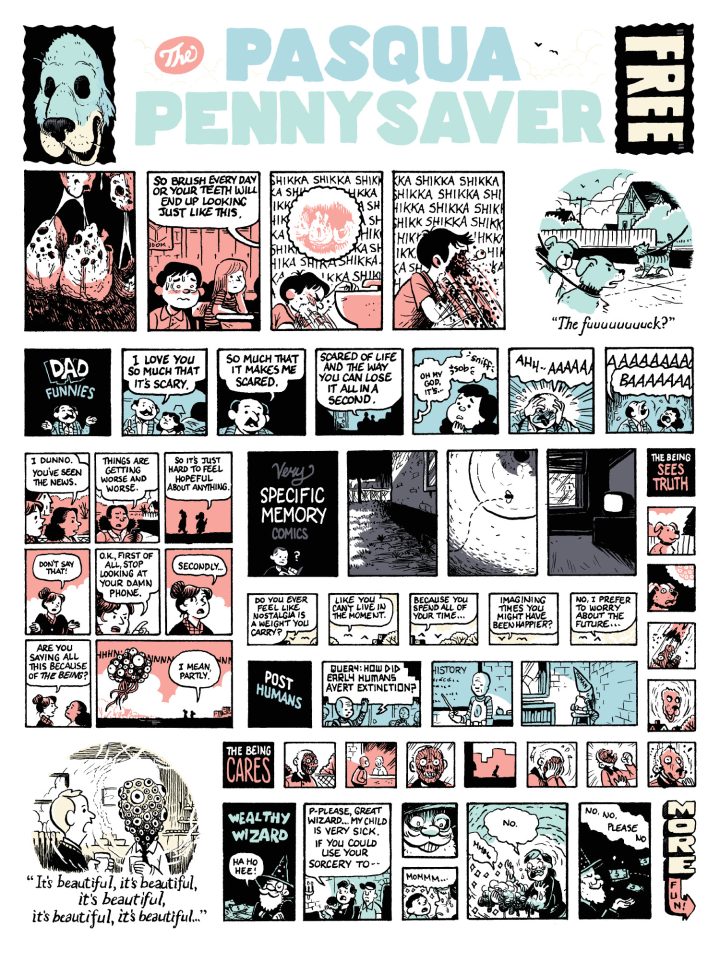

You are known for your dense, ambitious panel layouts. I remember your Taddle Creek magazine strip “The Pasqua Pennysaver” having 70 panels on one page! You’ve commented that this impulse derived in part from a desire to “take longer drawing comics while drastically reducing my page count.” Can you expand on this philosophy to make George Herriman-like comics that have a real sense of density and compactness?

I only vaguely remember saying that, but it’s a pretty funny line. Back in my hometown of Regina, Saskatchewan, an artist named Shawn McLeod started a comics anthology called Valuable Comics in 2005, and at one of our first meetings, everyone brought a bunch of different comics for inspiration. That was the first time I saw Chris Ware’s work, and it had a huge impact on me.

I love the way dense, little postage stamp-sized panels look. They have this rich, overwhelming texture when viewed as a whole page or a spread, but they also have the capacity to reward closer reading with overlapping, meandering threads and narratives.

I also find it very satisfying to draw little panels. Traditionally, comics are drawn large and then they’re shrunk down for print, which has a beautiful, tightening effect that can make things look more cohesive. But drawing small often seems to make my cartooning better because there’s no room for unnecessary details. Everything becomes distilled into icons, and I resist the urge to over-draw or crosshatch myself into oblivion. It’s hard for me to get away from the idea that taking a super long time on a drawing = a good drawing. That’s an old habit from when I was a teenager.

“The Pasqua Pennysaver” actually started around 2009 when I was saving up to attend CCS. I’d print the issues on a single double-sided sheet of letter paper, then clandestinely leave them in cafes around Regina for people to find. The panels wandered all over the page, so the reader would have to rotate the paper and read the strips in different directions. It was like having my own little nightmare page of the “Sunday Funnies.” I’ve been meaning to get back to it. In fact, there’s a half-finished one in my studio right now, but for some reason there’s very little money in giving away experimental comics, and I don’t seem to have as much free time as I used to.

You’ve done animation work for Netflix television shows like I Heart Arlo and Home: Adventures with Tip & Oh. What was it about storyboarding that interested you in the first place and were you able to apply any of the lessons you learned in comics to this other visual medium?

In 2014, Thurop Van Orman and Ryan Crego asked me to do a storyboarding test for Home: Adventures with Tip & Oh at DreamWorks after seeing some of my daily strips online. I’ve always loved animation, and it seemed like a fun opportunity. It also didn’t hurt that the job paid better than whatever I was cobbling together with illustration and teaching jobs at the time. I wasn’t in a position to move to L.A. but Thurop and Ryan were kind enough to let me work remotely.

It was so much fun. I learned so much in such a short time thanks to my first board partner, the brilliant and hilarious Jim Mortensen. There’s a lot of overlap between storyboarding and comics, though they’re not entirely the same, especially now that digital storyboards are expected to essentially be rough key frame animation. Comics are so much about guiding the eye through the page layouts, while storyboards are about motion and maintaining the audience’s gaze between the shots.

I learned to draw faster and clearer. I learned the value of coming up with way more ideas than you need, and to not be too attached to any of them because each episode is constantly changing after several check-ins, pitches, and rounds of notes. Doing a daily strip was good training for this because I already had the mentality that ideas are endless. I learned to be a better writer, with a greater understanding of story structure and character. There’s a writers’ room approach to board-driven shows that I found very exciting. I was also lucky enough to get to go to L.A. to pitch most of my boards in person with my board partners, and few things feel better than getting a laugh from a room full of funny people.

There are trade offs to the work — it’s a corporate job, and you don’t own any of the work you make. Boards for an 11-minute episode typically have a 5-6 week turnaround, so it can be grueling at times. I’ve heard some real production horror stories, but the people I worked with ran healthy, supportive crews, with room for a personal life, and no room for assholes.

I haven’t sought out storyboarding jobs since finishing my last contract at Netflix due to all the aforementioned everything, so I’m not sure if that bubble has burst, or how much the industry has changed, or if that’s still the kind of gig I could land working remotely now that I’m living back in Saskatchewan, but I’d work with any of those folks again without hesitation.

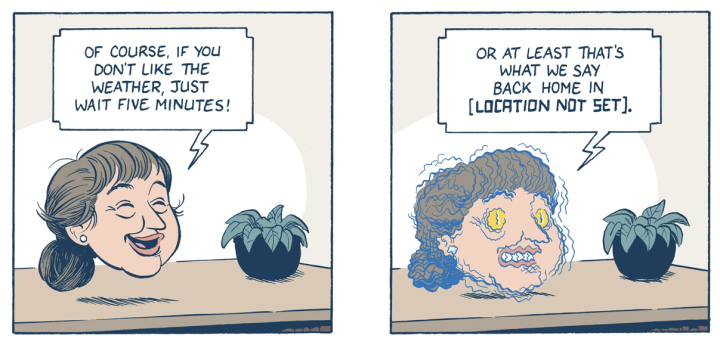

Your strip “The Latest in Virtual-Assistant Technology” was one of the rare times that the New Yorker ran a comic in their famous Shouts & Murmurs column. How did this strip come about, and what do you think it was about its merits that convinced editorial to run it?

There was a very brief moment in the 2010s when social media wasn’t absolute festering dog shit yet, so you used to be able to post art on Tumblr or whatever and it would sometimes lead to actual paying work. Emma Allen at The New Yorker reached out after seeing my comics online, and asked me to pitch some ideas for the Daily Shouts. I pitched a bunch of ideas, and they liked the virtual assistant comic along with one other. They were also running quite a few comics at that time, so it was a good fit.

This predates the nightmare LLMs we have now, but Siri and similar virtual assistants were popular at the time, so I guess they felt that there was something timely about a comic in which a virtual assistant scans your memories and becomes an avatar of your mother.

A lot of your releases like To Know You’re Alive and Untitled Bear Comic reflect your background in the zine world; these slim volumes are something that you can carry with you and revisit repeatedly. What’s the allure of playing with formats and sizes? How does making modifications to the “delivery system” in which a reader receives your work alter the context that they experience it in?

Similar to drawing comics, there’s something very immediate and available about making minicomics and zines. Even when I was a kid, my comics felt more “real” if I was able to get photocopies made of them. I made a minicomic with my brother, Jonah, before I was really aware of the wider world of zines. There’s something about seeing a copy of my drawings that helps me see it the way others might see it. Self-publishing was also deeply baked into the courses at The Center for Cartoon Studies, and most assignments had to be handed in as minicomics, with enough copies for the class and faculty.

The experience of reading a book is inherently more tactile and present in the physical world than something appearing on a screen, and there are more formal qualities to play with (scale, paper stock, screen printing, page turns, binding, etc.). Even when you’re not making full use of each of these qualities, every book exists in the real world as a unique object. Books can become dog eared, or ripped, or lent, or scribbled on, or fall behind a shelf to be discovered later.

A phone is always a phone; it’s always your finger sliding across the same piece of glass. It’s a vessel that can be filled with different things, algorithm willing. But we treat the contents as something that is flicked away to be infinitely replaced with more. That’s not to say that there aren’t formal considerations to digital comics, but the most available ways to deliver digital comics often carry a degree of sameness. For example, I generally prefer my comic strips to be horizontal, but if I want to post a strip on Instagram, I have to adhere to the same square format that everyone else is using.

I’ve certainly enjoyed making, reading, and benefiting from digital comics, but in terms of creative possibilities, making a book always feels more exciting and fulfilling to me.

You once described cartooning as a state of mind where “childhood never really ends and adulthood never really begins.” Do you still believe this to be true? To what extent does existing in this state of limbo hold the secret to forging a long and enduring path in comics? How do you suppose your work would change if you started to feel adulthood taking hold of your self-identity?

I only vaguely remember saying that, too. Good point, past self.

I think that can be true in a few ways. Lynda Barry has talked about the need for a sense of play when making art. She refers to it as a “cereal trance,” like a kid staring off into space while eating. It’s easy to take for granted just how bizarre imagination is. It’s a weird part of being conscious. You stare off into nothing and conjure images, scenarios, narratives, jokes, and then translate those into a form that others can experience. Eleanor Davis said making comics feels like playing in a dollhouse, and I think about that every time I work on a page. Making art is a form of play.

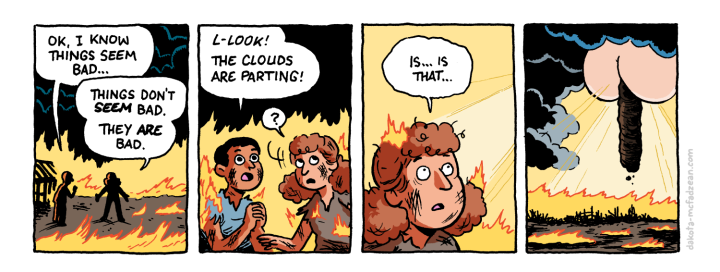

But there’s also something childish about being a cartoonist, and I sometimes feel this when speaking to other adults, neighbours, parents of my kids’ friends, my wife’s colleagues, etc. I don’t understand this feeling. I feel fortunate and proud to have the career I have. My siblings are all artists, there are artists in my wife’s family, most of my friends are artists, and I believe art is an important part of life, but it’s hard not to feel immature while talking to a nurse, or a civil servant, or a machine shop owner after spending my afternoon drawing a giant god butt in the clouds pooping on Earth.

The responsibilities and weight of adulthood have definitely affected what I make comics about because everything we experience affects the art we make. Before I had kids, a lot of my comics were kind of nostalgic and focused on memory and childhood, but now they tend to be informed by a wider perspective gained from parenting, too. Adulthood can also make it harder to get into that playful creative head space. Sometimes stuff just has to get done. Sometimes it’s difficult to want to play when you’re worried about a pandemic, or wondering what you will do if the U.S. actually does follow through on the fifty-first state talk. At the same time, play and imagination help us find our way through this stuff too. Other people’s art has helped me through hard times. Riding my bike while listening to Aesop Rock and Blockhead’s album Garbology played a huge part in helping me find my way through my pandemic funk. Making art has helped me to make sense of aspects of myself, others, and the world around me.

I think that your work has an element to it that feels like you are trespassing certain boundaries of what tones, styles, and themes can be combined — the way the absurd intermingles with young adult themes, for example. Do you think that comics is a medium where transgressive art can thrive?

That’s a big question. I think all art has the capacity to be transgressive, but it’s a spectrum. You can’t be transgressive in a kids’ television series in the same way that you can be in a photocopied minicomic intended for adults. Art is at its most interesting when it explores, challenges, and tests assumptions and expectations. What is art doing, if it’s not this? There’s room for things to be beautiful to look at, or simply entertaining, but isn’t it the best when art really affects the way you think about something?

The tricky thing right now is the way social media has affected the way we experience comics online. Well, and everything else, too. Everything is filtered through algorithms and engagement. Even when I was doing my daily strips, I would sometimes get caught in the trap of making things because they seemed like they’d get more likes (“this worked last week, so I’ll do another one like that ...”). It happens without me even being fully aware of it.

This drives repetition and homogeneity. There’s always been trends in art, of course, but the algorithms have also digitally herded us into echo chambers, and every echo chamber enforces its own orthodoxies. Add a sprinkling of corporate platform censorship, and it becomes increasingly difficult to see outside of what we’re being programmed to see, let alone push the boundaries of it.

But violating norms just for the sake of it quickly gets boring and shallow. For my part, I think I was more senselessly transgressive in my teens and twenties. With age and experience, I feel like I’m getting closer to making more nuanced work that digs into things that can’t easily be put into words alone. If I make a choice in a comic that surprises me, something that’s a few degrees removed from what’s expected, then hopefully it will resonate in some way with the reader too.

The post An interview with D. McFadzean: ‘It’s easy to take for granted just how bizarre imagination is’ appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment