I Ate The Whole World To Find You is a murky graphic novel. Rachel Ang's digital grease pencil drapes her pages in abyssal night, plunges into ocean depths, curls up within the confines of the womb. Caught amid the artists' murky depth is the graven image of one woman, Jenny, a tired, yearning soul, her posture drooping from years of manual labor and disassociation. I Ate The Whole World To Find You is at once a graphic novel and a short story collection, following Jenny across disparate moments of intimate reflection. Men appear throughout, lovers and exes, coworkers and abusive family members, and often speak but are rarely named, as if masculinity haunts the women in Jenny's world. That Ang's stories about Jenny chart a woman's grief, a woman's trauma, is evident at first blush, but there is no resolution, no call to action, no pat psychoanalysis, no throughline for understanding but empathy, and with empathy: horror.

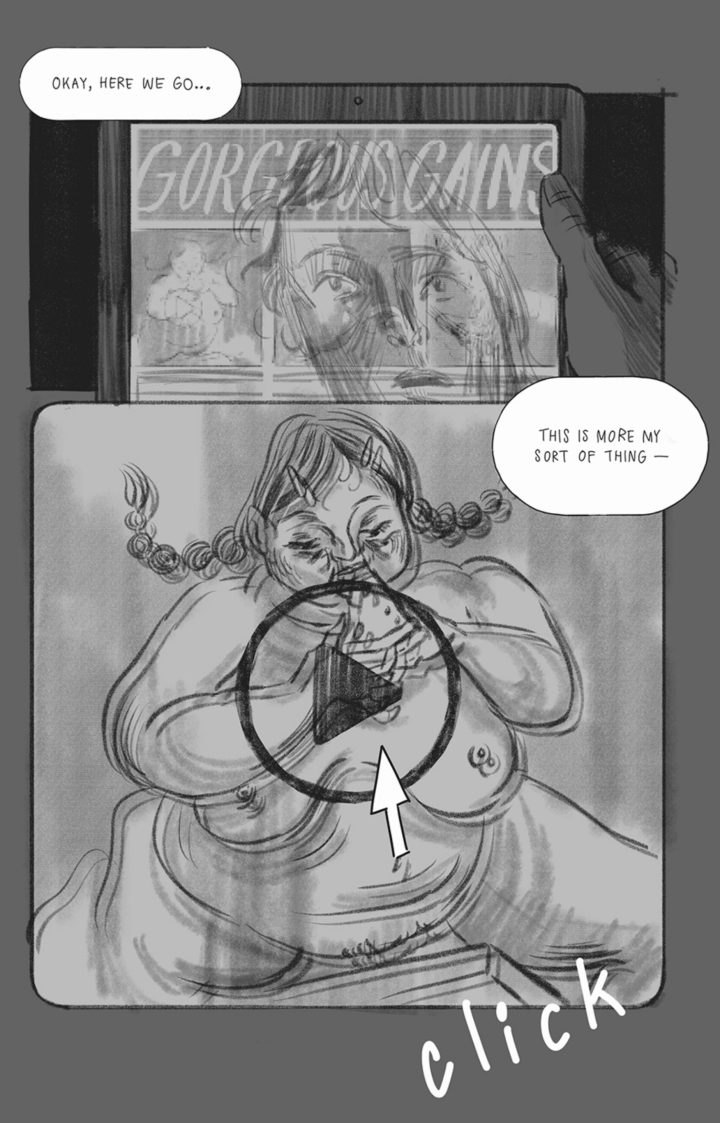

The first story, Hunger, initially appears to be a modern Bluebeard tale, but ultimately eschews the moral conventions of that narrative in favor of something far more haunted. Jenny falls for a male coworker, a man who shares her gallows humor and bears the tell tale signs of emotional exhaustion, a weary look on his face, attributed to a recently fumbled relationship. Gradually, he opens up to Jenny about his private obsession, feeder porn, a fetish fantasy centered around providing someone with so much food they become incredibly fat. Jenny is disinterested, maybe even disgusted, but looks past her lover's fixation, clinging to the freedom his companionship offers. His repeated assertion that everyone has a type now given a much clearer meaning, displays of affection become increasingly frightful to Jenny, who finds herself unable to enjoy the meals her lover happily cooks for her, a divide in their intimacy grows palpable. All Bluebeard stories end on discovering a secret cruelty to women of which our heroine is the next victim; Jenny walks in on her Bluebeard in his room, pitch black and illuminated only by the light of his laptop, vacantly editing a photo of her, distorted to massive proportions. Jenny cups her mouth in disgust, or maybe simply surprise, and fades into darkness for a moment. She looks at him, he looks up, startled, tries to hide his project which he cannot really explain. What should be a narrative denouement is a confusing, upsetting moment in time, a confrontation of the objectification which has become the unspoken firmament of their relationship, the impulsive unexamined sexuality that forms a wedge between the two, literally distorting Jenny into something she can never simply be. Does everyone really have a type?

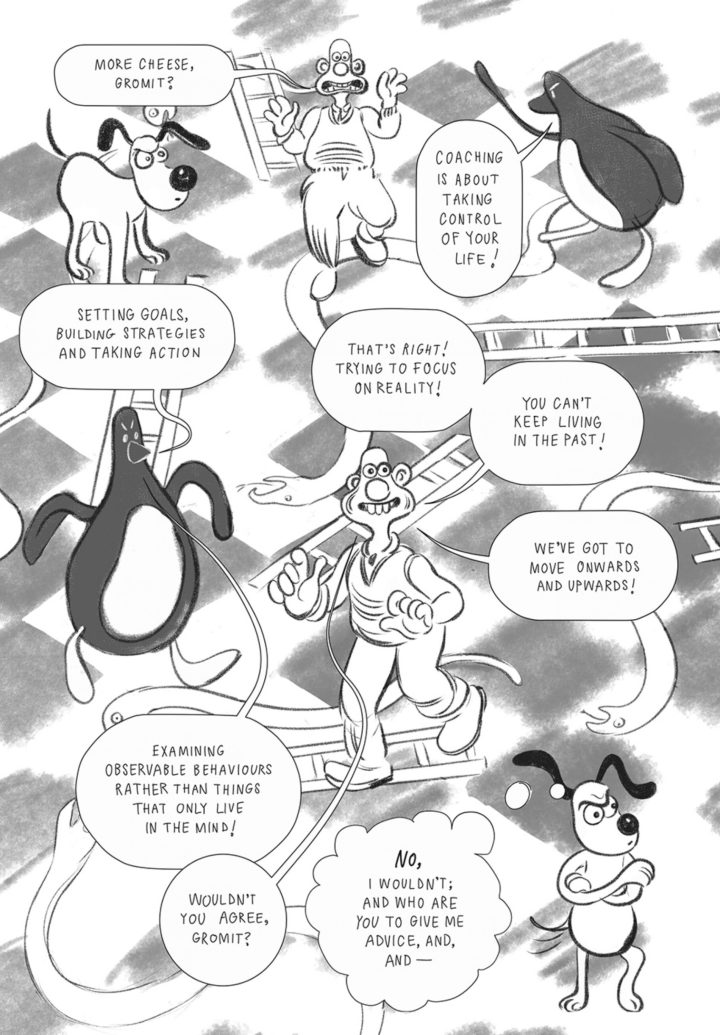

Much like the image of Jenny's body, the imagery in The Passenger is distorted, our first real journey into Jenny's interior reverie. On a train ride with an ex-boyfriend and his partner, Maxine, who is raising money for school to become a life coach. Jenny reacts cynically to Maxine's ambition, and the yet untrained teacher and her beau (mostly her beau) cast judgements on Jenny's negative outlook, and Jenny drifts into her anxious imagination, words peeling away into empty arrays of word ballons, speakers morphing into chess pieces, dogs, iconic cartoon characters, the train itself hurtling into a crumbling abyss, cracked apart by obscure hands, the freefalling anxious companions changing to animals and back as Jenny tumbles from the heavens into her bed. The light of her home, the immense form of her cat, seems far more forgiving than the judgements of her friends. Jenny escapes confrontation with the darkness of her inner world, the light of her room beckons through the crack of a door slightly ajar, a room where she is alone, maybe, or simply undisturbed.

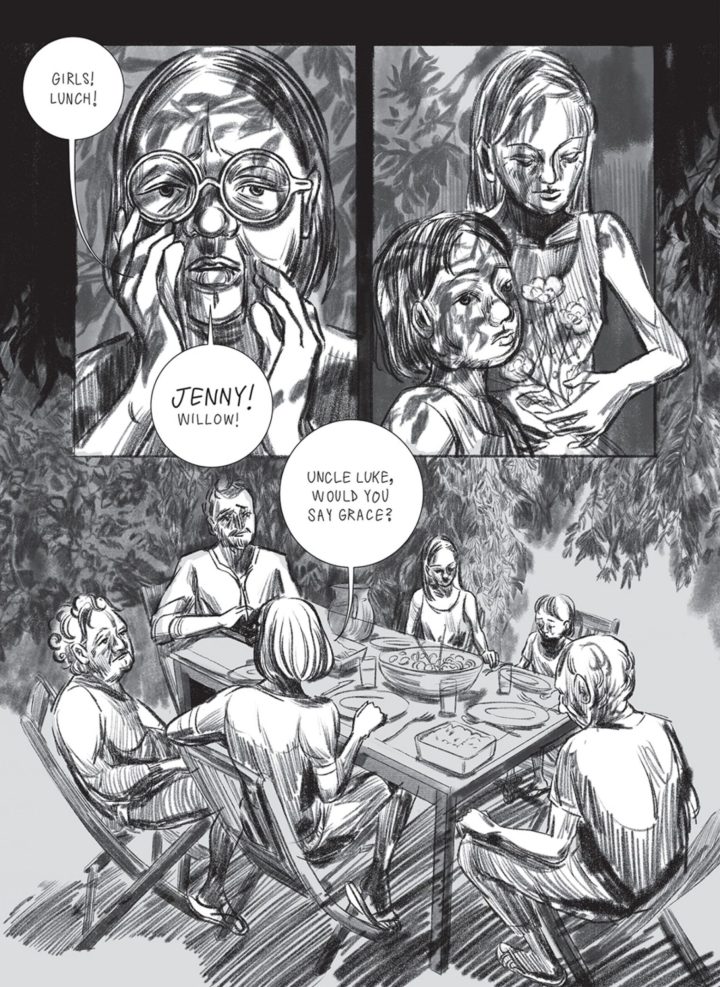

Your Shadow in the Dark begins where the first stories ended, an image of Jenny gazing through an open door. The story weaves between present and past meetings of Jenny and her cousin Willow. In the present, Jenny makes a house visit while Willow struggles with a limp which her doctors cannot identify the cause of. In the past, Jenny recalls childhood visits to cousin Willow and uncle Luke, the first named man in the book. Willow and Jenny play together, escaping to the beach from Luke's strict discipline, sometimes literally. In the present, Jenny takes the role which Maxine and friend took in the last story, enfuriating Willow with the suggestion her disability might be psychological in nature, which Willow rejects as a claim that her pain is not real. Departing in anger, both women in tears, Jenny remembers a night when uncle Luke crept into Willow's bunk bed, believing Jenny to be asleep. The sound of crashing waves fills the page, blotting out what could only be the sound of a parent raping his child. The adult Jenny awakes calling out her cousin's name. She dizzily wanders into their childhood bunk bed, runs into the woods to the beach.

The final two stories offer closure, but not resolution. In Swimsuit, Jenny reconnects with an old friend, the man she was dating in Hunger. In only a few years, maybe even months, the two find their lives have changed a lot. Swimming in a public pool, the two reminisce and chart the changes, but their reverie is interrupted when they become witnesses to a violent death, a group of white teenagers choking and drowning a black boy. Jenny's lover tries to move on from the freshly witnessed horror, but Jenny cannot look past the nightmare she just saw, one in which neither intervenes, she leaves to the silent darkness of her bed, and imagines herself submerged in the pool's water.

Purity is a visual and narrative poem, revisiting imagery from throughout the book as Jenny prepares to give birth to a child. Images of water, of curtains, of voices fading to oppressively blank balloons, pulse in and out of focus while Jenny observes in the darkness the form of her growing child. The veil, the darkness, the fear, what came before falls away as the hand of her newborn reaches out to her. Jenny hears a cry, she describes it in her narration, but it is not shown, the reader does not hear it as Jenny does. This might be the end of Jenny's life before this point, the beginning of a new chapter, a new life, but it is a life that begins with a cry. Perhaps it is as much that cry that Jenny has borne within her for a lifetime, expressed in this moment. Perhaps that cry, that fear and sadness at being is still within her, within anyone. What comes next?

Throughout I Ate The Whole World To Find You, Rachel Ang weaves the story of a life. It's a horror story, or more accurately a tragedy, a woman disappointed in her desire to love, to grieve, to be seen, in the face of violence, isolation, trauma, objectification. The door is always open a crack, the curtains stay a little open, moonlight cuts through the night. That light illuminates the horror perhaps, illuminating Bluebeard's face in the shadows, but likewise reveals Jenny, her love, her humanity, the kindness behind every frustrated connection and attempt to really love one another. Time and time again, Jenny gazes through a doorway. It might be a way out of her suffering, an entrance into an interior world, an exit from the room, the cite of a traumatic discovery. But in that moment, standing at the threshold, Jenny stands alive, the past behind her, the future ahead.

The post I Ate The Whole World To Find You appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment