Salem is America, and America is Salem. In this small Massachusetts town, originally populated by some of the most severe Puritans of the foundational era of this country, began the infamous witch hunts of the late 17th century, and in them, contained in miniature, were so many of the great sins that would form essential threads of America's DNA: the religious hysteria and misogyny of Protestant fundamentalists, our dishonesty and greed towards the indigenous population, our uncomfortable relationships with our European forebears, our curious blend of individualism and nosiness, and, most of all, our perpetual search for scapegoats upon which we can pin the failures and frustrations of our lives: All were present in Salem, and all have recurred, over and over, throughout our history, like the grim tolling of a familiar bell.

Along comes Ben Wickey, a writer, animator, and illustrator based in California, but originally from the same state that let Salem cast its shadow over the soul of America. A graduate of CalArts' lively drawing program, he scored big right out of the gate, contributing some memorable work to Alan Moore & Steven Moore's The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic. Like Moore, like Vivian Stanshall (a recent biography of whom he provided illustrations for), like Edward Gorey (whose work has been a near-constant touchstone in his career), and most of all, like Salem itself, Wickey stands in the nebulous space between the U.S. and the U.K., with his precise and fluid illustrations capturing much of the spirit of great British portrayers of the grotesque like Ralph Steadman and Gerald Scarfe, but very attuned to modern American sensibilities and with a flair for the domestic horror portrayed by natives like Drew Friedman and Charles Addams.

Wickey has set himself the gargantuan task of retelling the story of Salem within the framework of contemporary understanding but saturated in the authentic and absurd truth of its real historical context. Not only that, though, he has gone several steps further, filming that story with a literary and cultural lens that shows with care and intelligence why this particular incident has never stopped resonating, and never stopped recurring. More Weight is a truly epic work, ambitious and wide-ranging but never sprawling over its own sharp edges. It's incredibly dense, both in its thick dark inks and pools of washed colors and in its heavy, detailed text; it's one of the rare graphic novels which, already potent at over 500 intricate pages, seems like it would be even longer with the illustrations all stripped out.

Three different eras mark the focus of More Weight. The first is the story of the witch trials themselves, with a whole constellation of minor and major players, but with the great focus being on Giles Corey — a contradictory, difficult man with many good qualities and many hidden vices, but, above all else, a man who has allowed himself to become the kind of familiar small-town crank that everyone knows and everyone seems to have beef with — and his patient, practical, blameless, and tragic wife, Martha. His guilt and steadfast fury form the center of this part of the book, but it's by far the richest, most rewarding, and most thoroughly researched section, an absolute masterpiece of deep storytelling.

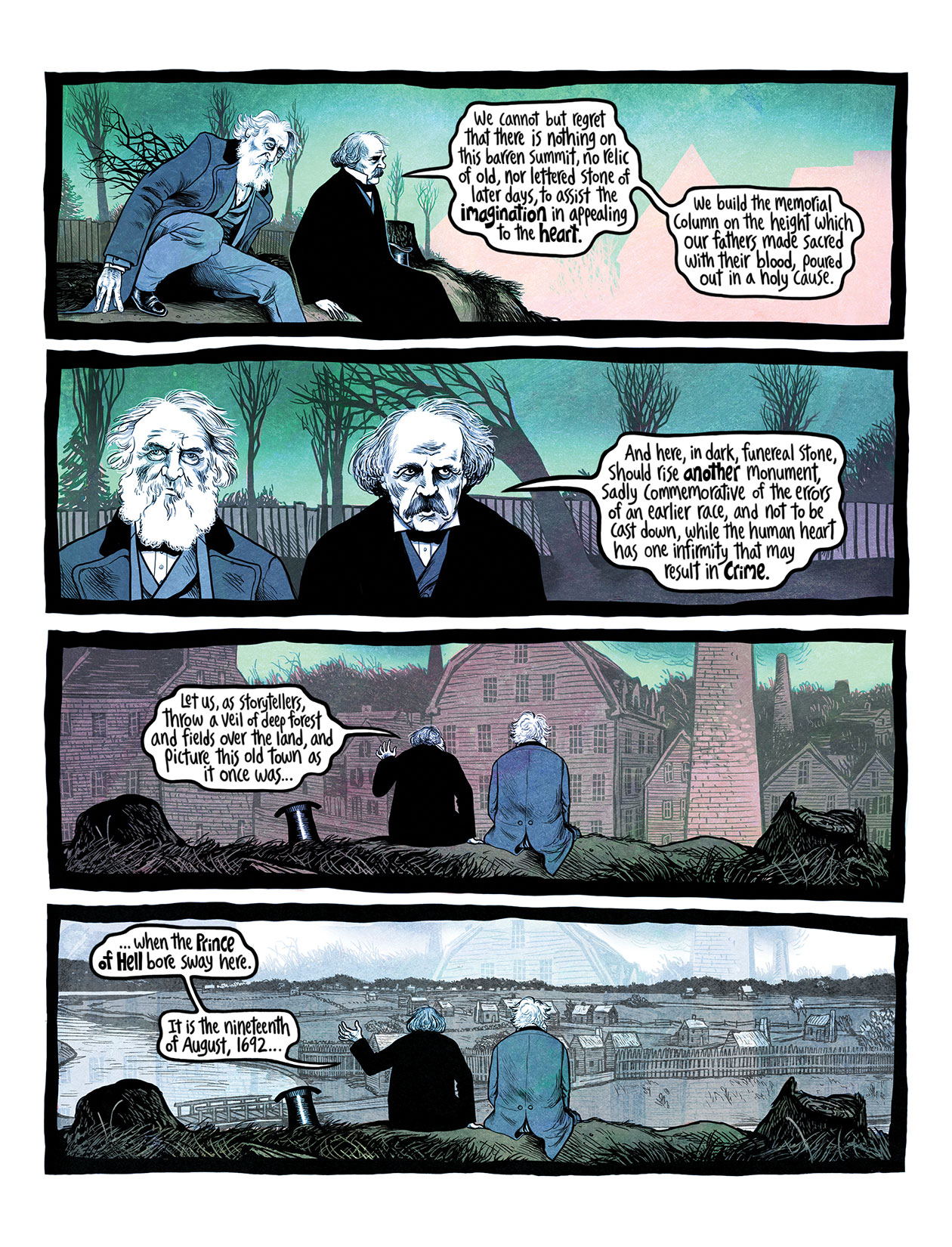

The next is the dreamlike conversation, almost two hundred years later, between Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Nathaniel Hawthorne as they roam the streets of an already-haunted Salem, considering the meaning of the witch hunts and struggling to understand their own roles in them. Collective responsibility and the difficulty of escaping the long reach of the past are the themes here, but in an even greater sense, these two figures – essentially American but even more deeply Early American – embody the way our whole culture and means of expression, not just our politics and our relationship to the past, are echoes of our bloody founding.

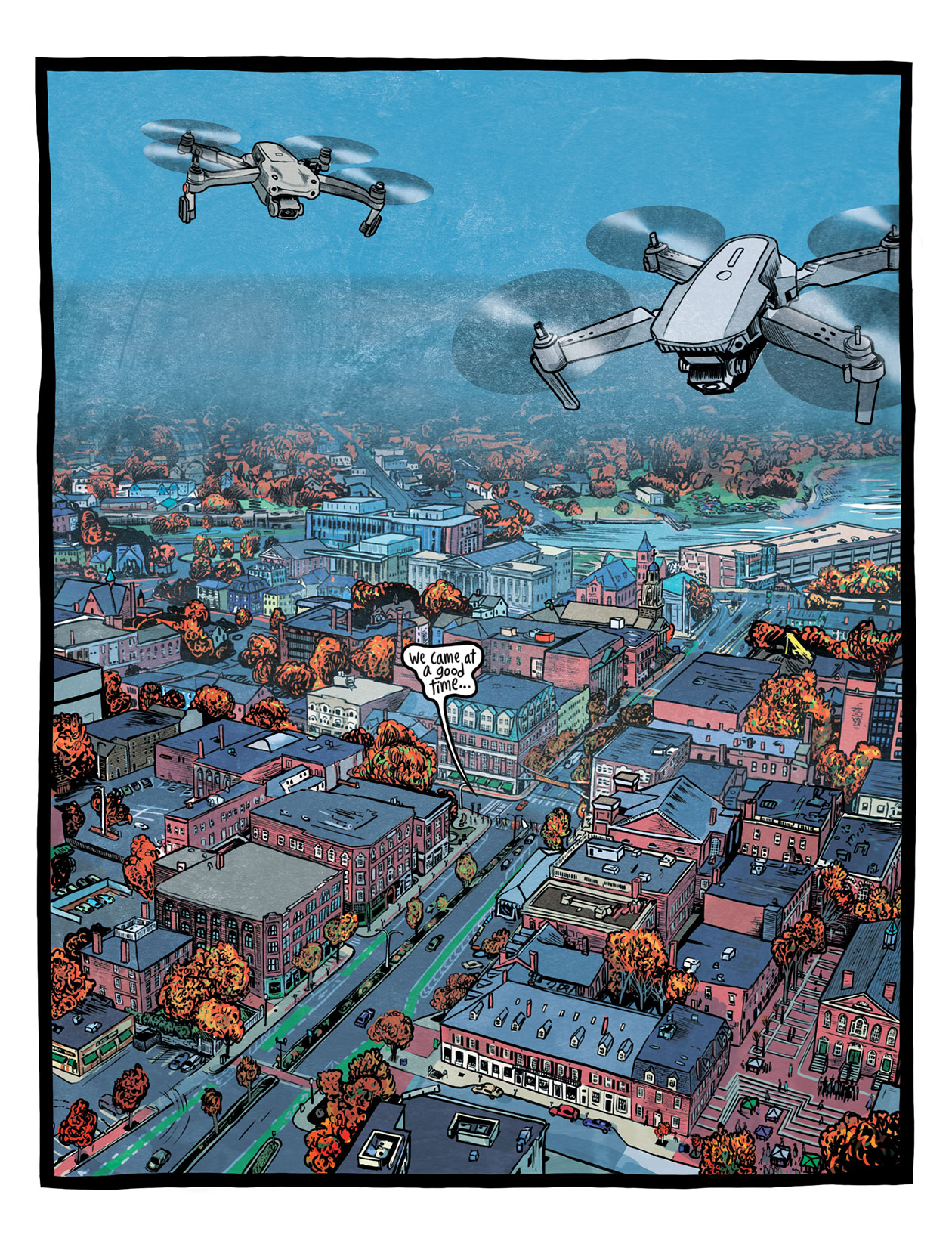

Finally, we see Salem today. This section is less graphically surreal and bizarre, and yet no less horrible for it, as a place infamous for injustice, religious mania, and mob mentality has come to convert that past into an advertising-driven tourism industry, with the ghosts of past tragedy reified into cheap entertainment for visitors. America excels at violence and fear, but even more than that, it excels at turning those things into content, at deciding there will always be more money in building a business around a problem than in coming to terms with it. The modern visions of Salem, in full bright color and a realism that damns, are Wickey's items in evidence of what we've truly learned, and their shine reflects on the past like a mirror, repeating the motions of what has come before.

Wickey's illustrations are magnificent throughout, always exaggerated, teetering ever on the brink of loose, careening madness, but always holding together. His cartoonish, forbidding faces make Salem's lunacy seem even darker while maintaining the sense of how ridiculous all of it was; every time the situation escalates, this blend of black humor and deadly earnestness drives home what a razor-sharp atmosphere must have permeated the town. In the 1860s, Longfellow and Hawthorne's sojourns have the quality of scrimshaw, shaded and dated, more suited to an illuminated text than a comic. And in the modern period, the vibrancy and color serves as a suitable distraction to the lessons we fail to learn. If it is not the best-drawn major comic of 2025, More Weight is at least the one whose art most successfully matches what its story is trying to accomplish.

The writing is more thorny and isn't always successful. Its intricacy and passion for documentation can make it seem more like reading a monograph than an entertainment, and it simply cannot be experienced casually; More Weight rewards close reading, but it also demands it. It can be easy, particularly in the highly attenuated sections with Hawthorne and Longfellow, to get lost; the cast of characters is immense and the narrative is slow and inexorable. But it is also, in the end, immensely rewarding, and the attention paid is attention well spent. In the tale of Giles Corey alone there is so much emotion, terror, paranoia, insanity, and intensity that even when it goes slightly astray, it presents us with stakes and escalations that surpass most of what I read in all of 2025.

More Weight has gotten some attention because of Wickey's recent work with Alan Moore, who kindly provided an accurate and adoring blurb for the book. It is especially unfair to burden a young, evolving talent like Wickey with a comparison to the world's greatest living writer in the comics medium, but it almost can't be helped. The comparisons to Moore's work are inevitable, and More Weight resembles to greater and lesser degrees many of the master's hallmark efforts, from Providence to Jerusalem. From Hell is an obvious parallel, with the two great American storytellers experiencing the full weight of the past on their stroll through Salem echoing William Withey Gull's architectural tour of London. But beyond the surface comparisons, both authors are intent on excising the whole of history out of the events of a specific time and place, channeling every black mark — racism, sexism, capitalism, colonialism, and every other stain on the national character — from the flawed and human interactions of just a few people. It is, as I said in my contribution to this publication's best comics of 2025 list, the most successful combination of art and story of this year.

The post More Weight: A Salem Story appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment